Written by Rafael Alvarez, Ron Cassie, Lauren Cohen, Bruce Goldfarb, Ronald Hube, Ken Iglehart,

Jane Marion, Jess Mayhugh, Amy Mulvihill, Gabriella Souza, Max Weiss, and Lydia Woolever

The birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution is tricky to get to. It’s not on any street map, but I can tell you how to find it. Take Lombard Street from downtown, continue past Hollins Market until you reach Monroe, and then make a left. After crossing the overpass, park at the City Farm-Carroll Park community garden. This is where it gets funky. You have to scramble down the hillside beneath the overpass, through woods and thicket—admittedly a surreal setting in West Baltimore—until you reach the clearing and train tracks.

If you go in the afternoon, follow the sun and tracks and start walking west. After a quarter of a mile, other tracks will merge into your path. You’ll pass a warehouse and a rusted steel edifice and start thinking you’ve gone too far and missed it. You haven’t. Amble on another five minutes, and suddenly what you’re looking for will pop into view on the right—a kelly-green, bellybutton-high metal box tagged with graffiti. Next to it, there’s a telephone pole tagged with graffiti, backed up by a stretch of abandoned boxcars and more graffiti, and behind that, a salvage yard.

It sounds underwhelming. The history born on this spot and marked by that green metal totem is anything but. Those tracks you’ve just walked down? Turn around. That rail line carried the first commercial passenger and freight trains in the United States. Turn back around, walk a little farther. See that? The 312-foot-long stone arch over the Gwynns Falls? That’s the Carrollton Viaduct. The first railroad bridge built in this country.

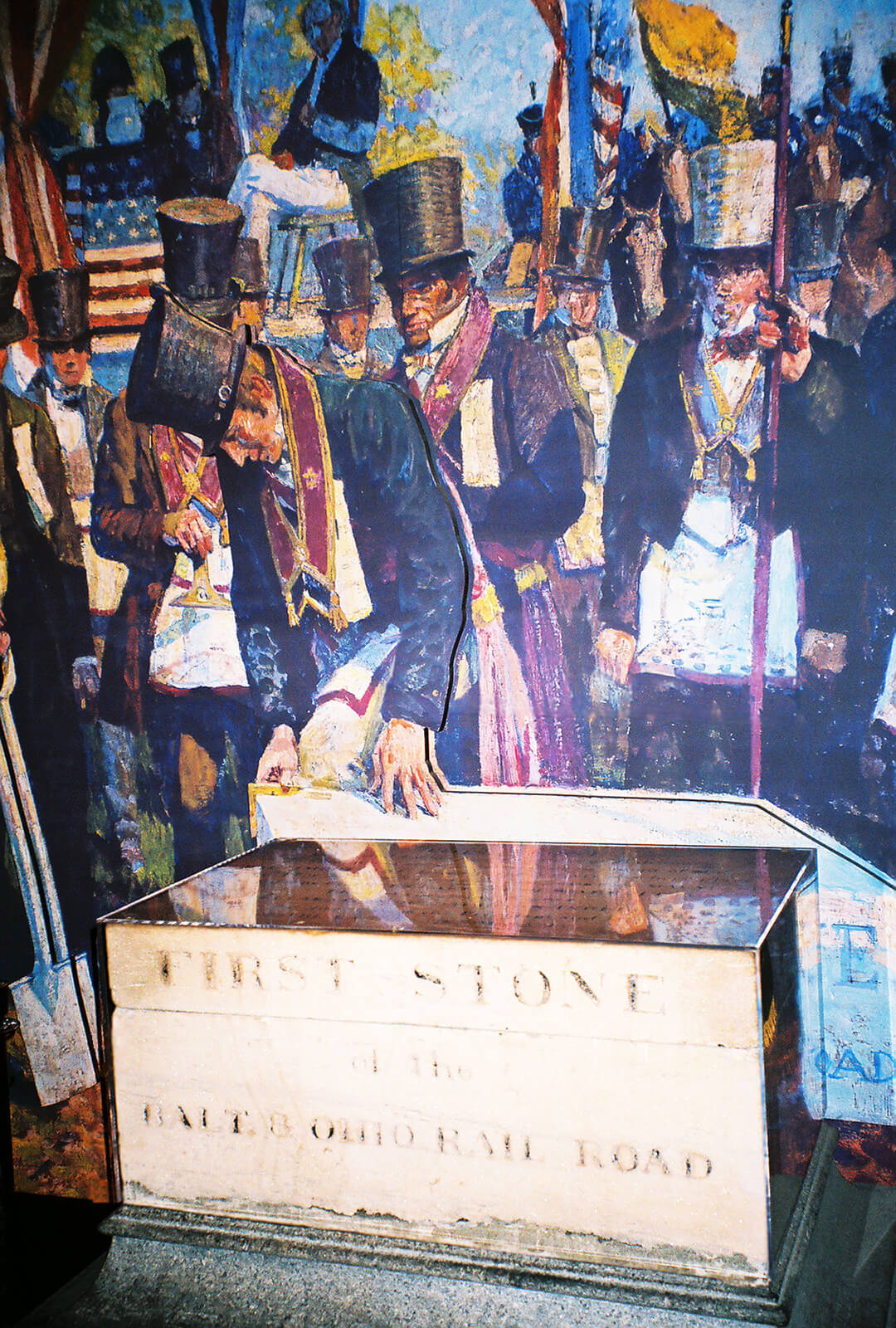

On July 4, 1828, Charles Carroll, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, put the first shovel into the dirt here for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. That green metal box is the exact location where the first stone, now kept in the B&O Railroad Museum on Pratt Street for safekeeping, was laid. (A replica sits inside the box). Three-fourths of Baltimore’s citizens gathered to celebrate the occasion with a four-hour parade. The 90-year-old Carroll told the crowd he considered the groundbreaking among the most important acts of his life, “second only to my signing of the Declaration of Independence, if even it be second to that.”

Two years later, the first 13-mile section reached the mills of Ellicott City with wagons pulled on the rails by horses. The steam engine was on its way, however. All along, Baltimore’s founding fathers, taking a tremendous risk on the untested railroad technology being developed in England, had hopes of extending the line through rocky Western Maryland and West Virginia (then Virginia) to the Ohio River. Still, it would take 25 years of hard labor and trial-and-error engineering before the first steam locomotive whistled through the Alleghenies and arrived in Wheeling on New Year’s Day, 1853. In terms of capital—and virtually every citizen of Baltimore had made an initial B&O stock purchase—nothing in the nation’s 75-year history came close to matching the cost of the $30 million project. But the city’s gambit to open the West and build on the economic advantage afforded by its inland, deep-water port would transform Baltimore, then the second-largest U.S. city, and the country like nothing else before or since.

It was an effort so bold, imaginative, and daunting that historian Herbert Harwood Jr. called it “the moonshot” of the 19th century.

When the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad became the first Eastern Seaboard line to reach the Midwest, it laid down the first link in a giant network that, after the Civil War, would integrate America into a single national economy. The B&O, of course, played a pivotal role in the Union victory, moving troops and delivering key intelligence, but it had also remained an innovator since its inception. The B&O made communication history when it became the first railroad to carry the U.S. mail in 1838. And then again, when it partnered with telegraph companies—the first communication technology of the Industrial Revolution—to string overhead wire next to its rail lines. (It is no coincidence that Samuel Morse’s first message in 1844—“What hath God wrought?”—sped in dots and dashes from the U.S. Capitol along the B&O’s right-of-way to Baltimore’s Mount Clare station.)

By the start of the 1860s, nearly 30,000 miles of rail and 50,000 miles of telegraph cable crisscrossed the country, obliterating previous conceptions of time and distance. In fact, it would be the railroad industry, in an attempt to standardize its schedules, which established the first U.S. time zones.

The launch of the B&0 was not the only seismic event in Baltimore in 1828, however. The formation that same year of an enormous real estate enterprise, the Canton Company—though not permanently memorialized like the B&O with a spot on the Monopoly board—would eventually remake Capt. John O’Donnell’s plantation into one of the great industrial waterfronts of the world. An Irish-born merchant seafarer and one of the richest men in the U.S. when he died, O’Donnell had amassed his 18th century fortune through trade in the Far East—including teas, silks, spices, and opium—naming his estate after the Chinese port.

The cornerstone of the B&O, now displayed at the B&O Railroad Museum, was laid July 4, 1828. Ninety-year-old Charles Carroll, the last surviving signer of the Declaration of Independence, told the crowd he considered the groundbreaking among the most important acts of his life, “second only to my signing of the Declaration of Independence, if even it be second to that.

A brief history: The incorporation of the B&O had sparked talk of an economic boom in the pubs, parlors, and boardrooms of Baltimore. In the spring of 1828, Columbus O’Donnell, the captain’s eldest son, and William Patterson, donor of the first acres of the park that bears his name, met with Peter Cooper, a New York capitalist and inventor, to pitch their plan to buy all of the property from Fells Point to Lazaretto Point—the entrance of the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel today. Convinced of the benefits the B&O would endow to Baltimore’s port, Cooper bought a major stake (the only stake, it would later turn out) in the new Canton development corporation, which was given the right to purchase up to 10,000 acres by the state of Maryland. Think Port Covington times 40 in a city with 80,000 people. Two years later, worried his entire investment would be lost as the B&O struggled to create a viable steam engine, it was the polymath Cooper who took it upon himself to design and construct the first successful American-built locomotive—aka the Tom Thumb.

(According to lore, Cooper’s coal-burning prototype raced a horse-drawn car to prove its worth, leaving its steed-powered competitor in the dust before a belt snapped. Bottom line: Although the Tom Thumb lost the race from Ellicott City to Baltimore, Cooper’s steam engine design won the day.)

“I call 1828 the ‘big bang.’ That was the year it all came together and Peter Cooper’s the lynchpin,’’ says Raymond Bahr, a retired physician, Canton native, and local historian, who hopes to create a museum in Canton honoring the community’s industrial past. “Between the B&O and the Canton Company, which is the earliest, largest, and most successful industrial park in America, Baltimore stands at the intersection of U.S. commerce and trade, and technological advances in transportation and communication.”

With its world-renowned Clipper ships, Baltimore already led the nation in shipbuilding when the Canton Company was launched. The USS Constellation, the first U.S. Navy ship ever to set sail, had also been built in a shipyard at Canton’s Harris Creek—the shipyard and creek both long since buried beneath the Boston Street Safeway.

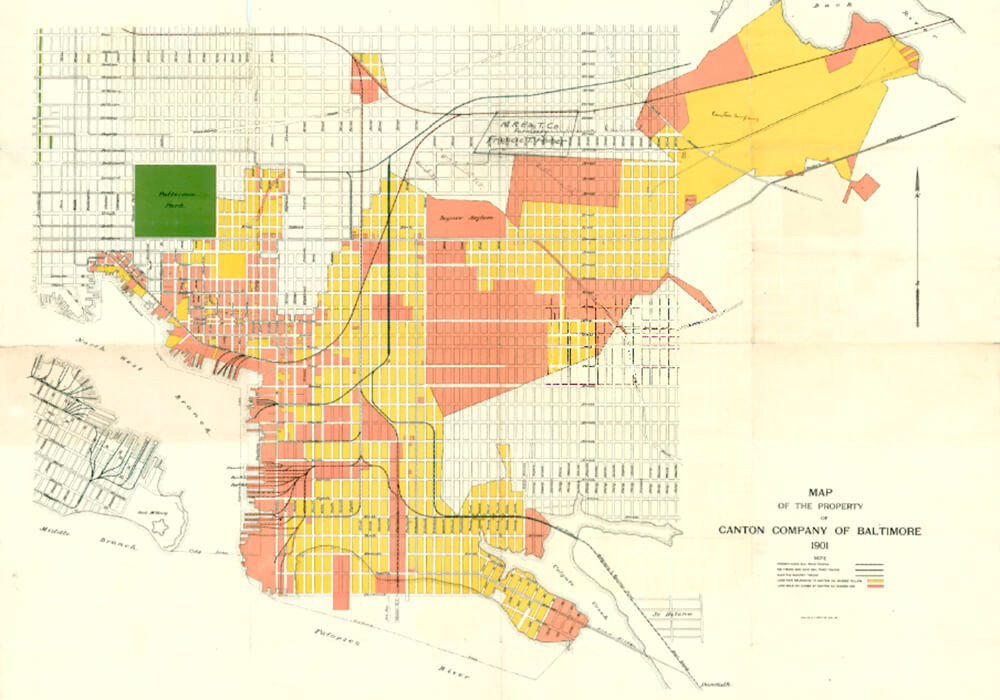

In 1828, new Canton Company development corporation, was given the right to purchase up to 10,000 acres by the state of Maryland,and it became the earliest, largest, and most successful industrial park in the U.S.

In the ensuing decades, the Canton Company slowly began to lease, sell, and develop its vast holdings. At its peak, it owned a swath of land that stretched from Fells Point to Patterson Park—across all of Highlandtown—to the Baltimore County line. Not long after the Canton Company was founded, nearby oyster beds and the city’s expanding rail and labor force would establish the city, and Southeast Baltimore in particular, as the canning center of the U.S. (See: the American Can Company complex.)

Shipbuilding, lumber, iron, coal, and canning companies followed on the waterfront—as well as cotton duck and steel-rolling mills, distilleries, beer makers on Brewers Hill—and the largest U.S. copper smelting plant. Some 69 manufacturing companies were in business by 1871. The Canton Company built wharves and piers and initiated two railroad ventures of its own the Union, later bought by the Northern Central, and the Canton Railroad. If you’ve ever kayaked in the harbor off the Canton Waterfront Park and wondered about the towering steel structure in the water there, it’s the remnant of a massive lift that once pulled railcars—crossing on barges from Locust Point—onto Canton trains.

Major oil refineries arrived, too. Up until 1925, Oklahoma crude was still being sent via pipeline to Baltimore for refinement in Canton.

But the Canton Company was developing more than just an industrial powerhouse. It laid out Southeast Baltimore’s familiar grid streets and its iconic—and then inexpensive—rowhouses for its blue-collar workers. (The proximity of Baltimore’s industry and marble rowhouse stoops in neighborhoods like Canton would prove a bonanza for Bon Ami cleaning powder.)

And, now long forgotten, Canton even flourished as a thriving summer destination. With music and dance halls, roller coasters, a roller rink, a shooting gallery, taverns, restaurants, and a swimming pier, it was billed as “the Coney Island of the South,” drawing 600,000 visitors a season at the turn of the 20th century.

The intertwined origin stories of the B&O and the Canton Company are crucial to understanding the history of Baltimore—and subsequently the United States—because nearly everything that happened during the city’s boom over the next century and a half is connected, one way or another, to those two landmark events. George Peabody, William Walters, and Enoch Pratt were each involved with the B&O. Johns Hopkins became one of the directors of the railroad in 1847 and bequeathed his vast B&O stock holdings to fund the city’s elite university and hospital.

The immigration pier at Locust Point—the second or third busiest in the country (depending on the year)—was built by the B&O after the Civil War, delivering thousands of Eastern and Central European workers into the port’s factories. That pier also welcomed the German-born Otto Mergenthaler, who would invent the modern typesetting machine and send U.S. literacy rates skyrocketing. It also welcomed Sen. Barbara Mikulski’s Polish Catholic grandparents and Sen. Ben Cardin’s Jewish grandparents.

When Bethlehem Steel joined the industrialization of the port in 1916, it amassed the largest steel plant in the world at Sparrows Point.

Those jobs, as well as others around the port—at General Motors, Lever Brothers, Western Electric, in the rail yards—also attracted African Americans to Baltimore. It’s no surprise that both Thurgood Marshall and his father worked for the B&O.

– Sean McCabe

It is also no surprise that Baltimore, so long on the cutting edge of modern America—from the moonshot of the B&O to the camera that captured Neil Armstrong walking on the moon—produced so many peerless innovators. It’s a list that includes geniuses as varied as Abel Wolman, who perfected purified public drinking water, and Eubie Blake, whose hands are enshrined in plaster casts at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

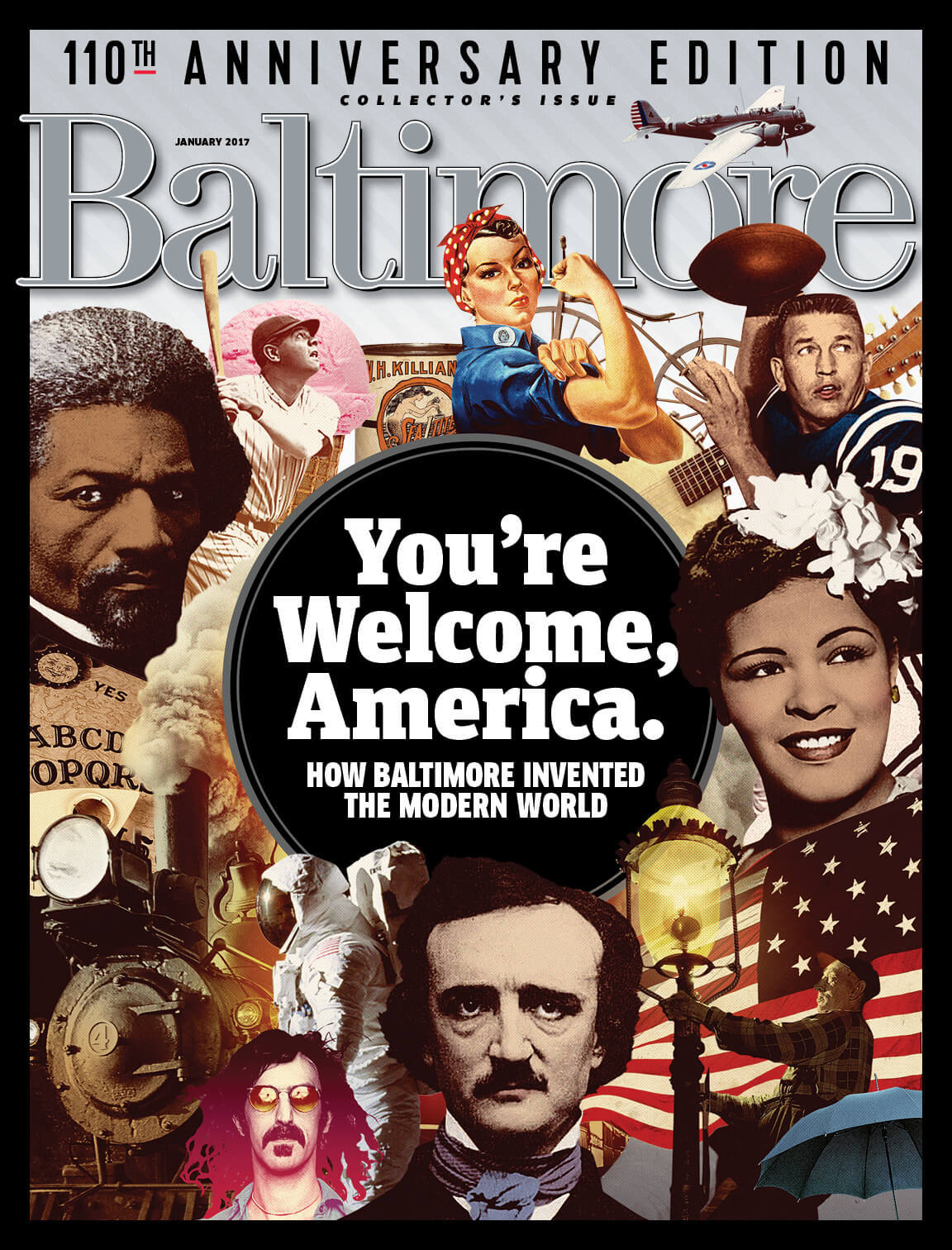

In the following pages, we list 110 ways that Baltimore helped invent modern America. The number is a nod to Baltimore ’s 110th anniversary as the oldest continually published city magazine in the country. More importantly, the list is a reminder that Baltimore was—and is—one of America’s greatest cities. We tried to put the city’s most prominent contributions up top, but the list is largely chronological. We don’t pretend to be able to discern whether the invention of the electric streetcar is more significant than the invention of the submarine, or whether Billie Holiday or the Baltimore Colts had a more profound cultural impact. What we do know is that in Baltimore, we walk in the footsteps of giants every day.

—Ron Cassie

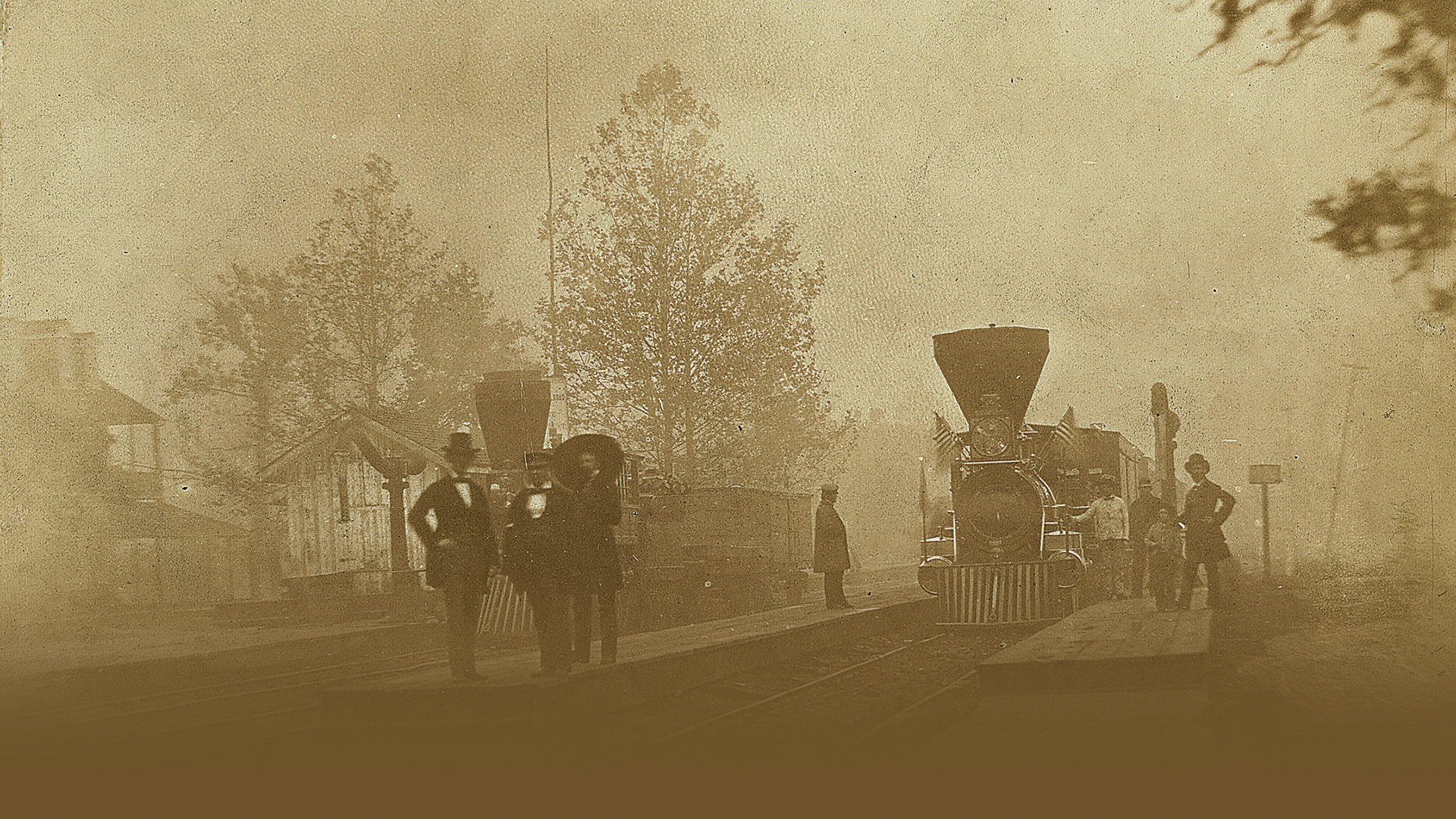

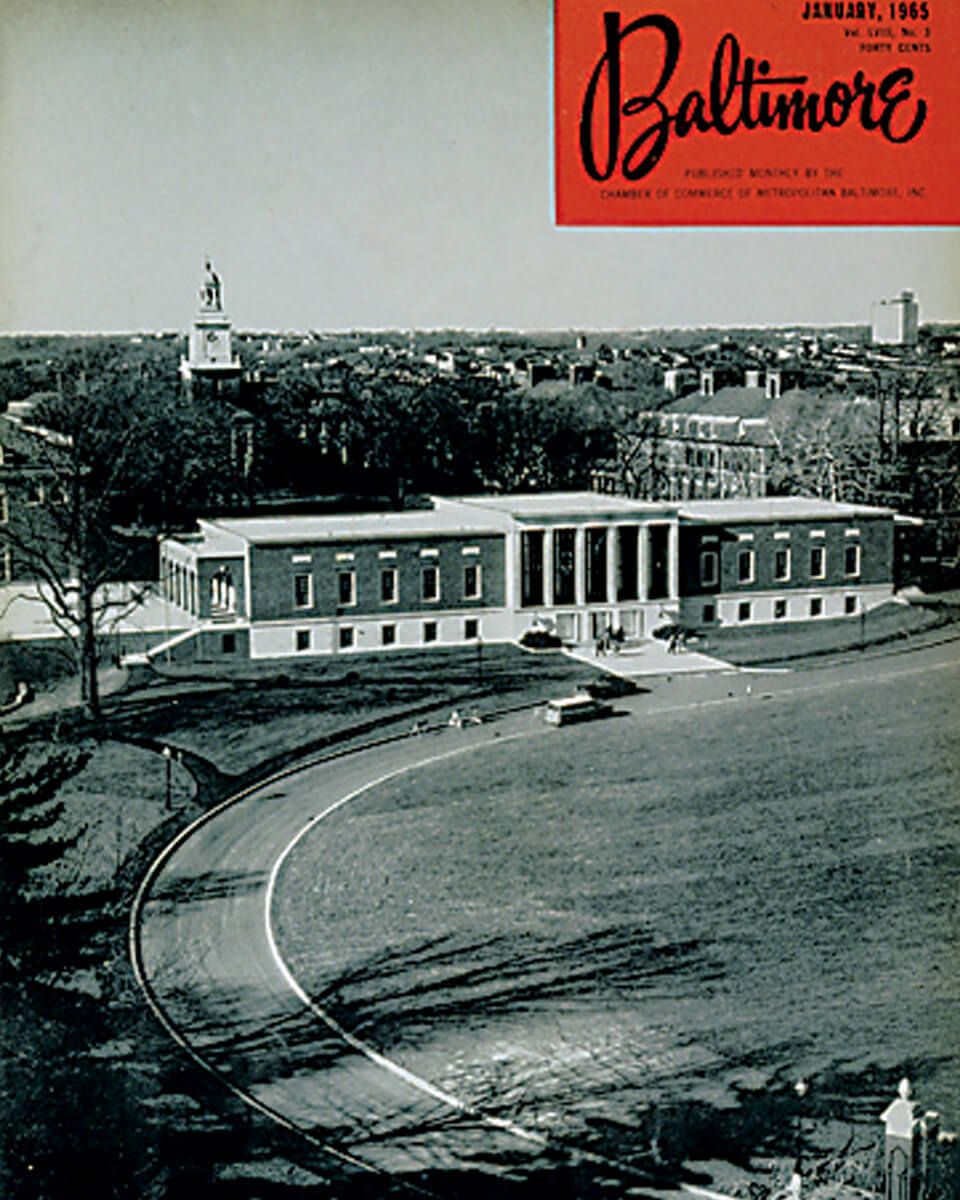

COURTESY OF the maryland historical society, PP262.06

1.

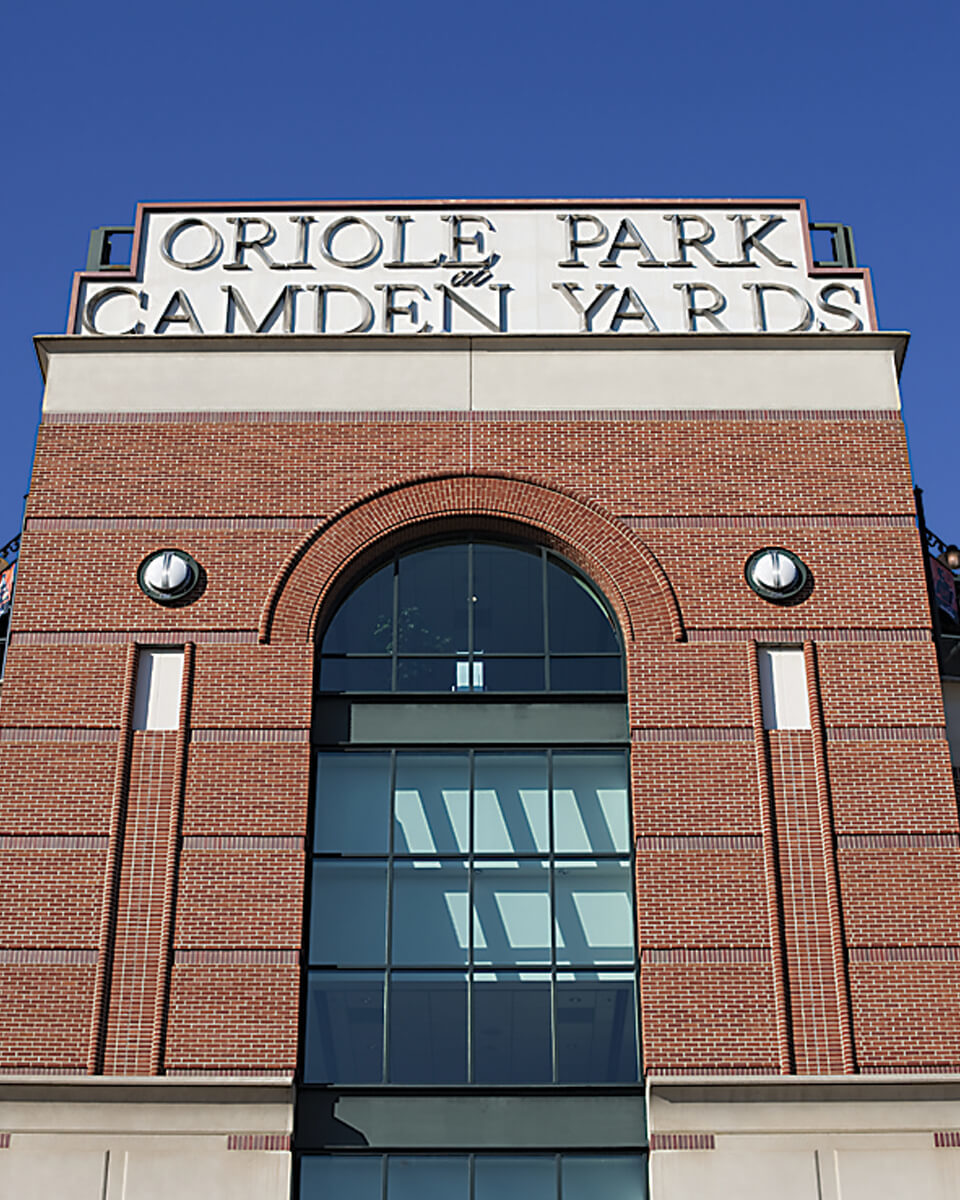

THE Baltimore and Ohio RAILROAD is launched

in 1828 and later opens the midwest

In the way that Apple was not the first computer company, the Baltimore and Ohio was not the first railroad in the United States, but it was the most innovative and transformative. On May 24, 1830, after laying 13 miles of rail connecting Baltimore to the mills of Ellicott City, the B&O changed the way people and goods traveled when it launched the first operational passenger and freight railway. With the newly completed Erie Canal linking New York to the Midwest, and canals in the works in Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., Baltimore’s leading merchants and bankers—afraid that the city would lose the economic advantage the Port of Baltimore afforded—gambled on the new, largely untested railroad technology being developed in England. Cutting and blasting through Western Maryland’s rocky terrain, it would be 25 years before the B&O became the first rail line from the Eastern Seaboard to reach the Ohio River and truly open the West. In the process, the B&O played a groundbreaking role in locomotive design and railroad engineering—the first U.S. railroad bridge, the 1829-built Carrollton Viaduct over the Gwynns Falls, remains a marvel—as well as in commerce, finance, mass transportation, and communication. The B&O’s other great legacy is the crucial role it played during the Civil War, when president and Baltimore native John Garrett sided with the Northern side, providing the Union Army with key intelligence and its most important supply line.

2.

THE STAR- SPANGLED BANNER

(STAR-SPANGLED BANNER ENGRAVING) COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

As the shelling of Fort McHenry began Sept. 12, 1814, more than 4,000 British troops landed on North Point Peninsula, planning a shock and awe march toward Baltimore. Instead, Maryland's militia gave the overwhelming British forces all they could handle, delaying them long enough for the earthen buttresses in today’s Patterson Park, built by local citizens—including free blacks—to successfully protect the city. The massive 42-by-30-foot flag commissioned by Maj. George Armistead, who specifically ordered “a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty in seeing it from a distance,” was sewn by widowed Baltimore seamstress Mary Pickersgill . And, of course, it held up under the ensuing 25-hour bombardment as Francis Scott Key chronicled the Battle of Baltimore in epic verse.

3.

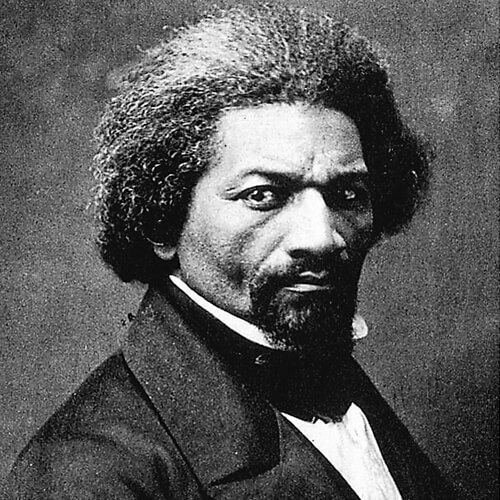

FREDERICK DOUGLASS ESCAPES TO FREEDOM

Born on an Eastern Shore plantation, Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in Baltimore on Sept. 3, 1838, and became a prophet of universal human rights like few before or since. Sent to work as a caulker on Baltimore’s docks, the 20-year-old Douglass, who had secretly taught himself to read and write, jumped a train for Philadelphia while impersonating a free black sailor. His 1845 memoir, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, sold out its 5,000-copy first run in four months, quickly becoming one of the most important pieces of literature of the abolitionist movement. Two years later, Douglass founded The North Star, an influential Rochester, New York, newspaper with the slogan, “Right is of no Sex—Truth is of no Color—God is the Father of us all, and we are all Brethren,” while agitating for abolition, women’s suffrage, desegregation, and public education. He was also the first African American to receive a nominating vote for president.

4.

BABE RUTH SAVES BASEBALL

The self-confessed “bad kid” born on Emory Street in Pigtown, Ruth’s wayward life was saved by baseball at St. Mary’s Industrial School before he went on to save the game itself following the Black Sox scandal of 1919. With 714 home runs fueled by hot dogs, beer, a voracious sexual appetite, the torso of a bear, and the hand-eye coordination of a fighter pilot, he was Elvis times 10 on the scales of American celebrity. When the street kid grew up, he never forgot where he came from, either—bringing the St. Mary’s Industrial School band along on road trips to help it raise money after a fire at the school.

5.

THE National road GETS AUTHORIZED

Known in many places as Route 40 today, the National Road was authorized by the Jefferson Administration and became the country’s first federally funded road. Supplementing the Western Maryland gateway to the Midwest, the state legislature linked several routes from Baltimore to Cumberland—creating the Baltimore National Pike—to connect the city’s port and economic engine to markets from West Virginia to Illinois.

6.

Thurgood Marshall OVERTURNS SEGREGATION

Oliver Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas , was brought to the Supreme Court by the father of a third-grade girl forced to ride a bus to a “colored” school rather than be allowed to walk to a closer—and better—white elementary school. It was the same saga that played out in the lives of thousands of Baltimore schoolchildren and, undoubtedly, was a familiar story to Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP’s chief counsel representing Brown before the Supreme Court. An alumnus of Frederick Douglass High School, Marshall had spent two decades winning smaller but critical civil-rights and education legal battles—including several in Maryland—that set the stage for the 1954 landmark desegregation victory. “Inherently unequal” was the phrase Earl Warren used in crafting his first major opinion as chief justice on May 17, 1954, striking down the “separate but equal” principle that had long governed American public education. Baltimore’s public school system, led by Walter Sondheim Jr., was the first district south of the Mason-Dixon line to comply. Marshall, the great-grandson of a slave, was on his way to establishing himself as a seminal figure of the civil rights movement and the American judicial system. In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson nominated him to the U.S. Supreme Court, where he served until 1991.

7.

FIRST POST OFFICE SYSTEM

Experiencing censorship by the British postmaster, Baltimore printer William Goddard responded by designing a uniquely American system founded upon the principles of open communication and an exchange of ideas free from governmental interference. His plan—the Constitutional Post—was adopted in 1775, “ensuring communication between patriots and the populace during the American Revolution,” according to the National Postal Museum.

8.

FIRST CITY STREETLIGHTS

Courtesy of The Contemporary, 2016

We didn’t invent gaslights (the Chinese did), but Charm City did bring them to the U.S. The credit goes to painter Rembrandt Peale, who fired up a gas-fueled chandelier in his home museum of artwork and eclectic things (think mastodon bones) in 1816, using “carburetted hydrogen gas.” Though the novelty was at first only for the wealthy—and actually pretty dangerous, since there was no way to measure gas volumes—Peale and a partner soon convinced several businessmen to found the nation’s first gas company, which became Baltimore Gas and Electric and just celebrated its 200th year. Then Peale and company talked the city into lighting Baltimore’s streets with the potentially explosive stuff. Reports of the first lamp being lit in 1817 noted “that the effect produced was highly gratifying to those who had an opportunity of witnessing it, among whom were several members of the Legislature of the State.”

9.

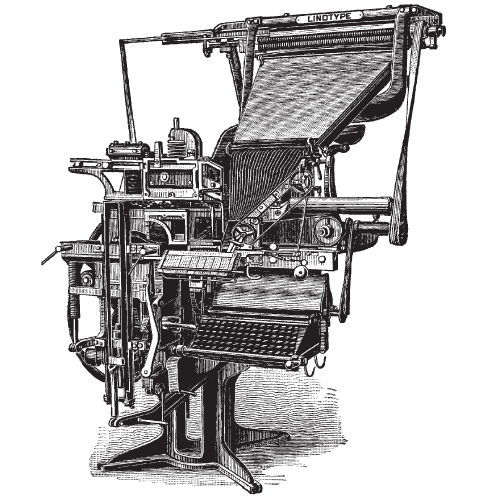

MODERN printing press

Printing technology in the mid-1800s was still pretty much mired in the mid-1400s, which was when Johannes Gutenberg developed a novel but laborious typesetting method requiring each letter to be set manually on a plate. But that all changed thanks to Baltimore’s Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German immigrant and watchmaker who—after a few false starts and some inspiration from an absurdly complex machine envisioned by author Mark Twain—developed the first typewriter-like typesetting machine in 1884. (Thomas Edison subsequently called it “the eighth wonder of the world.”) The New York Tribune quickly demonstrated the first commercial use in 1886. According to Mergenthaler’s son, Herman, “When Tribune publisher Whitelaw Reid saw Ottmar type on the keyboard and shortly after witnessed a thin metal slug bearing several words slide down into a tray, he exclaimed, ‘Ottmar, you’ve done it! A line o’ type!’ Thus the Linotype machine was born.” One stunning effect? In the first decade of its use, American newspaper readership went from 3.6 million to more than 33 million.

10.

Clean Public Drinking Water

Before the 20th century, tap water carried diseases such as cholera, dysentery, and typhoid. Chlorine was known to kill disease-causing microbes since the 1850s, but it is also a powerful poison for humans. Native son Abel Wolman, a Hopkins-trained engineer, devised how to chlorinate water safely in 1919, making clean drinking water possible for the world and saving millions of lives in the process.

11.

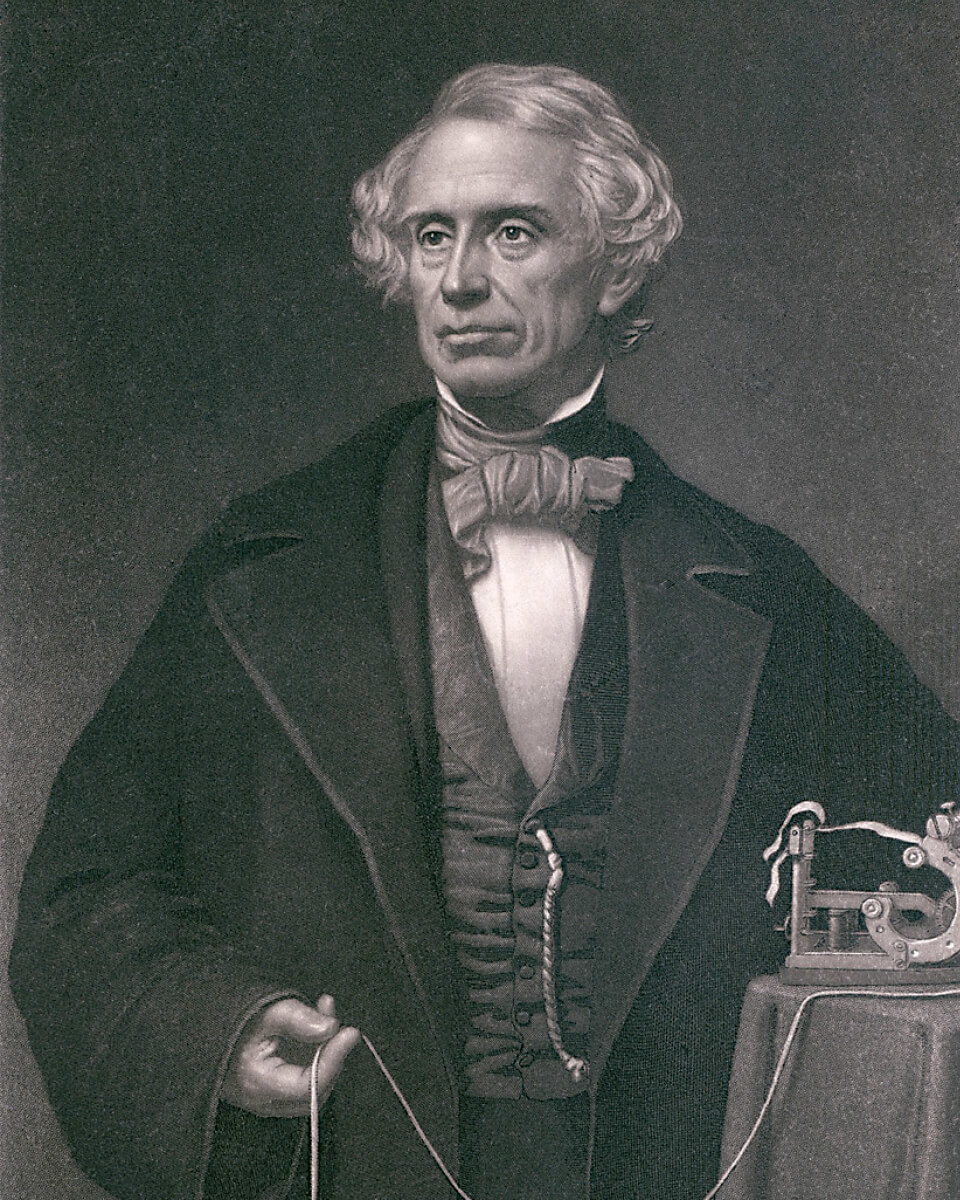

FIRST TELEGRAPH SENT FROM D.C. TO BALTIMORE

On May 24, 1844, using the language of dots and dashes that he would become famous for, Samuel Morse sent the first successful long-distance telegram from the U.S. Capitol to the B&O’s Mount Clare Station 38 miles away in Baltimore. Among those gathered in Washington were presidential candidate Henry Clay, former first lady Dolley Madison, and Annie Ellsworth, daughter of the patent commissioner, who selected the telegraph’s first message—“What hath God wrought?”—from the Bible. After fellow inventor Alfred Vail transcribed the message in Baltimore, he and Morse discussed the weather and current events in each city. Morse’s coded message sped along cable lines strung beside the B&O’s right-of-way, foreshadowing a deep partnership: Within 10 years, more than 20,000 miles of telegraph wire crisscrossed the U.S.

12.

ENOCH PRATT FREE LIBRARY SYSTEM

On Jan. 5, 1886, businessman Enoch Pratt brought one of the first free public libraries to the American people—and not one just intended for the elite and Anglo intellectuals, like others at the time. Instead, Pratt offered an egalitarian vision of his city athenaeum—one “for all, rich and poor without distinction of race or color.” Within three months of its Mulberry Street opening, four new branches popped up, and by fall, the library issued its first borrower’s card to an African American. More than 130 years later, across 23 locations, the library honors Enoch’s original mission—through holidays, storms, and uprisings, from Pennsylvania Avenue to Hamilton.

13.

WORLD’S FIRST Dredger

INVENTED In 1783, flour mill owners John and Andrew Ellicott invented what became known as the Baltimore Mud Machine—a horse-drawn barge with a scoop that removed sediment from the harbor so ships could reach their warehouse at Pratt and Light streets. In 1827, a steam engine replaced the horses, creating the first non-animal-powered dredger.

14.

clipper ships SAIL TO RESCUE

Baltimore—and the once separate Fells Point —share a salty heritage, and one of their 18th-century claims to fame is the development of the Baltimore Clipper, a fast, short-keeled schooner designed to haul cargo through the Chesapeake area’s shallow tributaries and rivers. With cannons mounted on them, they excelled at harassing British shipping during both the Revolution and the War of 1812, eluding deep-draft British warships with their maneuverability. Want to see one? Our Pride of Baltimore II is a pretty accurate replica.

15.

LARGEST CANNING CENTER IN THE U.S.

Courtesy of the BGE Photograph Collection, Baltimore Museum of Industry

Canning was discovered by an early-19th-century confectioner and brewer in France, who recognized that cooked food stored inside a seal-tight jar did not go bad. In the U.S., canning enterprises first introduced in Boston and New York were brought to Baltimore, where the industry was perfected in the mid-1800s with the region’s plentiful oysters—a boon to both Baltimoreans and their countrymen, who’d become enthralled with the flavorful staple of the Chesapeake. In the 1850s, local canner Isaac Solomon, advancing an innovation of a British chemist, introduced salt to the boiling process—raising the boiling point and speeding up the cooking time of oysters. From oysters, the canning industry exploded around the Port of Baltimore, where packers became the first in the country to can corn and tomatoes, which were culled from the fertile soil of Central Maryland and the Eastern Shore. In 1874, Andrew Shriver, ancestor of Maryland’s famous Shriver clan, invented the retort kettle—aka the pressure cooker—further cutting cooking times and costs, while also industrializing canning operations. By 1889, there were 82 canned goods packers along the waterfront, including Platt & Co. (now home to the Baltimore Museum of Industry), with the city and the mid-Atlantic area serving as “the nation’s pantry” until California’s emergence in the 1920s.

16.

The Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Protesting pay cuts in July 1877, B&O firemen in Baltimore, and rail workers in Martinsburg, West Virginia, launched the first national strike. The uprising spread to 14 states before it was broken up by the U.S. Army. By then, more than 100 people had been killed, including 11 Baltimore citizens. The strike served as a precursor to the successful, broader labor actions of the 1880s and 1890s.

17.

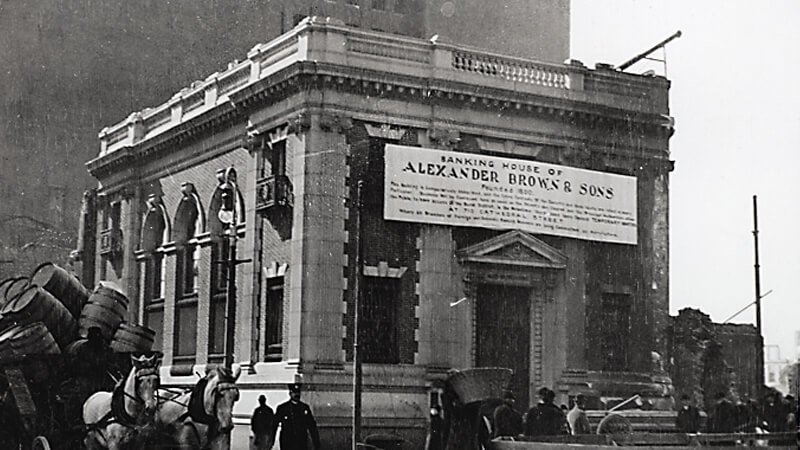

ALEX. BROWN FIRST INVESTMENT BANK

Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center. All Rights reserved

America’s oldest continuously operating investment bank sort of stopped being a local thing when Bankers Trust Corp. bought it in 1997—two years before Deutsche Bank AG swallowed up both Bankers Trust and Alex. Brown for more than $10 billion. But the history is interesting: Founded by, you guessed it, Alexander Brown, in 1800, it operated as a linen trading firm on Gay Street before morphing into an investment bank and brokerage house. It became known nationally for such feats as financing early utilities companies, Baltimore’s first water system, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In modern times, it made financial headlines for taking companies public, including Microsoft Corp. and Starbucks Coffee.

18.

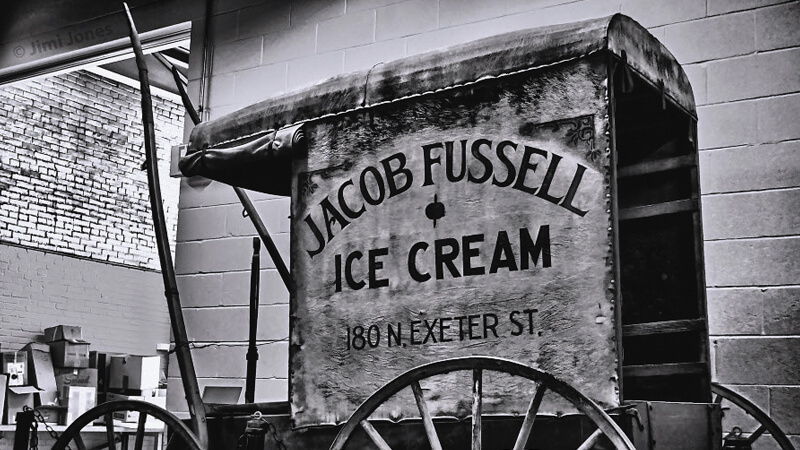

first U.S. ice cream factory

Jimi Jones Visuals LLC

In 1851, after a dairyman defaulted on a debt for his catering business, which sold a frosty blend of milk, eggs, and sugar, Baltimore milk dealer Jacob Fussell took over the business and soon created the nation’s first large-scale ice cream factory. Once an exotic treat, the cold stuff became wildly popular and Fussell was dubbed “the Father of the Ice Cream Industry.” Movie stars Tony Curtis and Piper Laurie were among the city’s special guests at its giant centennial ice cream celebration in 1951—10,000 free cups were handed out.

19.

THE FIRST AMERICAN BICYCLE

Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History

After learning of a human-powered, two-wheel vehicle gaining popularity among Europe’s “dandies,” Baltimore piano-maker James Stewart built the first U.S. velocipede—a precursor to the bicycle with pedals attached directly to the front wheel—in late 1818. Capturing the country’s imagination after the Civil War, influential early innovators held public bicycle races around Druid Hill Park and by the 1880s, as the sport took off, Baltimore hosted national meets of the League of American Wheelmen. No less than H.L. Mencken described learning to bike ride in 1898 as a “great and urgent matter.”

20.

FIRST U.S. sugar REFINERY

Domino Sugars might dominate the Charm City skyline today, but more than 100 years before that sweet factory was built on the Inner Harbor, America’s first sugar refinery was opened in 1796 in Baltimore by a little known German company, Garts & Leypoldt.

21.

Banjo History

Despite its affiliation with predominantly white musical genres like country and bluegrass, the banjo traces its lineage to the “plucked lutes” brought to North America (including Chesapeake Bay plantations) by West African slaves. By the 1840s, the instrument’s popularity had exploded, crossing over to the white mainstream through minstrel acts. Soon after, in a factory on East Baltimore Street, William Boucher became the earliest known commercial banjo manufacturer, standardizing the instrument’s design in the process. Now Boucher banjos rightfully reside in collections at the Smithsonian and the Met as prized pieces of Americana.

COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

22.

FIRST ELECTRIC STREETCAR runs from

Baltimore city to Hampden

Streetcars were catalysts in the rise of the modern American city, linking urban dwellers to work, retail, and recreation destinations with unprecedented speed, convenience, and reliability. They were also pulled by horses initially, and in Baltimore, the original line from Charles and 25th streets to 40th Street and Roland Avenue in Hampden was full of such steep grades that mules pulled the cars. In 1885, the Baltimore & Hampden company contracted with a British professor and immigrant named Leo Daft, who had been experimenting with an electric rail design in New Jersey, to see if he could replace the teams of mules. Using cutting-edge technology, Daft’s system employed a charged third rail between two parallel tracks, and operated mule-free for four years until its infrastructure wore out. Although the line then returned to animal power, its development was an immediate hit, and it is considered the first successful commercial electric railway in the U.S. Of course, its “live” third rail was also dangerous, and it spurred the development of a safer and more efficient form of electrically powered street transportation—specifically, overhead wires. In 1899, two early streetcar companies merged in Baltimore, forming the United Railways and Electric Company, and the city’s mass transit system was on its way. By 1926, more than 1,300 streetcars, gliding on more than 430 miles of track, were toting an average of 710,000 people daily through the streets of Baltimore. The last two streetcar lines to operate, the No. 8 (Towson-Catonsville) and No. 15 (Overlea-Walbrook Junction), ceased operations in the early Sunday morning hours of Nov. 3, 1963.

23.

PIONEERING WOMEN EDUCATORS

Cecilia Lawrence, www.theophilia.deviantart.com

In the late 1870s, five spirited suffragettes from prominent Baltimore families made a weekly tradition of meeting to discuss art, literature, poetry, and philosophy. Among them were M. Carey Thomas and Mary Elizabeth Garrett, founders of the Friday Evening Group, who joined forces to create equal opportunities for women in education. In addition to shaping the curriculum at Bryn Mawr College, where Thomas later became president, the duo founded The Bryn Mawr girls’ preparatory school in Roland Park in 1885. With a huge financial assist from Garrett, who became known as a sharp businesswoman after inheriting a hefty portion of her father’s estate, the ladies also helped establish The Johns Hopkins Medical School under the condition that both men and women be admitted.

24.

First Monument to Edgar Allan Poe

Best known for his narrative poems and macabre short stories, such as “The Raven” and “The Tell-Tale Heart,” Edgar Allan Poe is also widely considered to have invented the modern detective story with the creation of fictional detective C. Auguste Dupin, who appears in the stories “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” “The Mystery of Marie Roget,” and “The Purloined Letter.” It’s believed Poe penned eight of his published poems and nine of his short stories at his residence on Amity Street—home to the Edgar Allan Poe House and Museum today. Dying of mysterious causes in Baltimore after being discovered delirious and semiconscious outside a saloon on an October night in 1849, he reportedly prayed his final words, “Lord, help this poor soul,” on his death bed. Initially buried in an unmarked grave, a campaign for a memorial—“Pennies for Poe”—was started in 1865 by a local teacher, leading to his marble headstone at Westminster Hall, where it remains a tradition for visitors to place a penny atop his grave.

25.

First american saint

A young widow who converted to Catholicism, Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton (1774-1821) fled religious prejudice in her native New York City and moved to Catholic-friendly Baltimore at age 33. She was canonized by Rome in 1975 after a miracle attributed to her—a healing bestowed upon a Baltimore girl suffering from acute leukemia (she attended a now-defunct high school named in Seton’s honor) was accepted as genuine. She also founded the first Catholic religious order for women in the U.S.—the Sisters of Charity—in Emmitsburg, which is home to her national shrine.

26.

First Flour Mill

Constructed in 1792, the Ellicott Flour Mill in the small Baltimore County town of Oella, on the east banks of the Patapsco River, is said to be the first merchant flour mill in the U.S. Built by brothers John, Andrew, and Joseph Ellicott, the mill complex proved successful enough to serve as the initial terminus of Baltimore’s B&O Railroad.

27.

First u.s.monument to washington

Our Washington Monument is nearly 400 feet shorter than that more famous one on the Potomac, but it was built more than 50 years sooner, making it the first public monument to the Father of Our Country. Designed by architect Robert Mills (who later would plan the D.C. obelisk) and built with local white marble, it inspired the city slogan “The Monumental City”—apparently coined (a bit sarcastically—what a surprise!) by a Washington newspaper editor in 1823.

28.

First Museum Building

On a quiet stretch of Holliday Street, America’s first building designed as a museum once housed the works of Leonardo da Vinci, Diego Velázquez, and Raphael. The Federal Period-style townhome was co-founded in 1814 by Rembrandt Peale, a prolific portrait painter and man of many firsts who would go on to found the country’s first gas company, aka BGE. His museum remained open until 1829, when it was turned into Baltimore City Hall, then the city’s first high school for African Americans, and later a longtime municipal museum, before a long span of vacancy. Relaunched as a nonprofit in 2008, the organization is now working to raise funds to restore and reopen the Peale Museum, but in the meantime, it’s innovative legacy lives on. The building continues to present modern art projects and exhibits, including last spring’s breathtaking Only When It’s Dark Enough Can You See the Stars by The Contemporary and Abigail DeVille.

29.

First dental college

During the first early years of America, dentistry was relegated to untrained and self-trained practitioners, quacks, and a few doctors. In 1840, Horace H. Hayden and Chapin A. Harris founded the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery—first of its kind and soon a prototype for others across the country. More than 175 years later, the institution thrives as the University of Maryland School of Dentistry.

30.

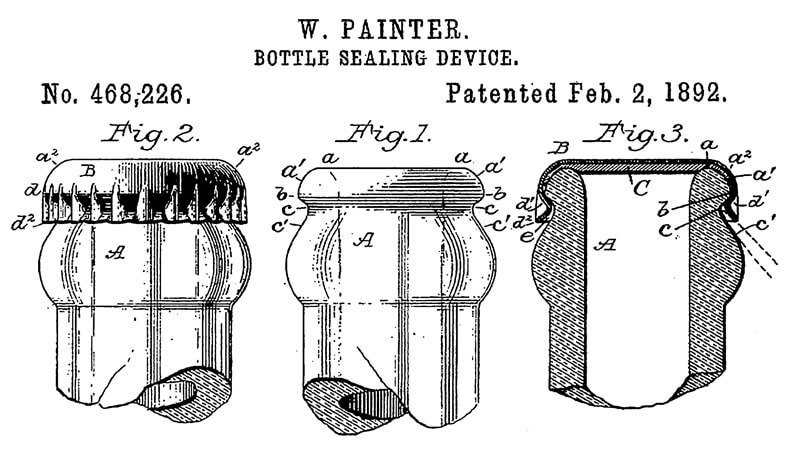

Invention of the bottle cap

Where wouldhumanity be without an ice-cold bottle of beer after a long day? Well, thanks to Baltimorean William Painter, we’re able to seal those beers with the bottle cap, which he invented in 1891. Soon after, every beverage company in the world was looking to Painter (who also invented, naturally, bottle openers) for his brilliant caps. He opened the Crown Cork and Seal Company in 1897 on Guilford Avenue, moving it to Highlandtown in 1906, where it remained until leaving for Philadelphia in 1958.

31.

AFRICAN-AMERICAN JOURNALISM

Baltimore-born abolitionist, poet, and writer Frances Ellen Watkins Harper penned the first published short story, “The Two Offers,” by an African-American author. Harper, who helped slaves escape through the Underground Railroad, also wrote prolifically for black newspapers, becoming known as the mother of African-American journalism.

32.

LOCUST POINT immigration pier

welcomes 1.2 million immigrants

COURTESY OF the maryland historical society, MC4733.6

Ellis Island in New York has long cast a shadow over immigration in other U.S. cities. However, from the construction of the Locust Point immigration pier in 1867 until its closing in 1914—the period between the Civil War and the start of World War I—approximately 1.2 million mostly Central and Eastern European immigrants streamed into the South Baltimore peninsula, making Baltimore the second or third busiest U.S. port of entry (depending on the year) for new arrivals. By the 1890s, an estimated 90 percent of immigrants arriving at the Locust Point Pier, which had been built by the B&O Railroad, traveled directly to a destination farther west. But the rest stayed here, many working in the port’s burgeoning canning, steel, garment, shipbuilding, railroad, and manufacturing industries. Baltimore’s Immigration Museum opened this year in an historic German boarding house in Locust Point.

33.

FIRST BLACK TRADE UNION

In 1855, Isaac Myers, a former Baltimore shipyard supervisor, founded a maritime industry union of “colored mechanics.” In 1866, Myers and more than a dozen other African-American men formed their own enterprise, the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company. Three years later, Myers, one of nine black delegates to attend the National Labor Movement Convention, helped launch the Colored National Labor Union, of which he was elected president.

34.

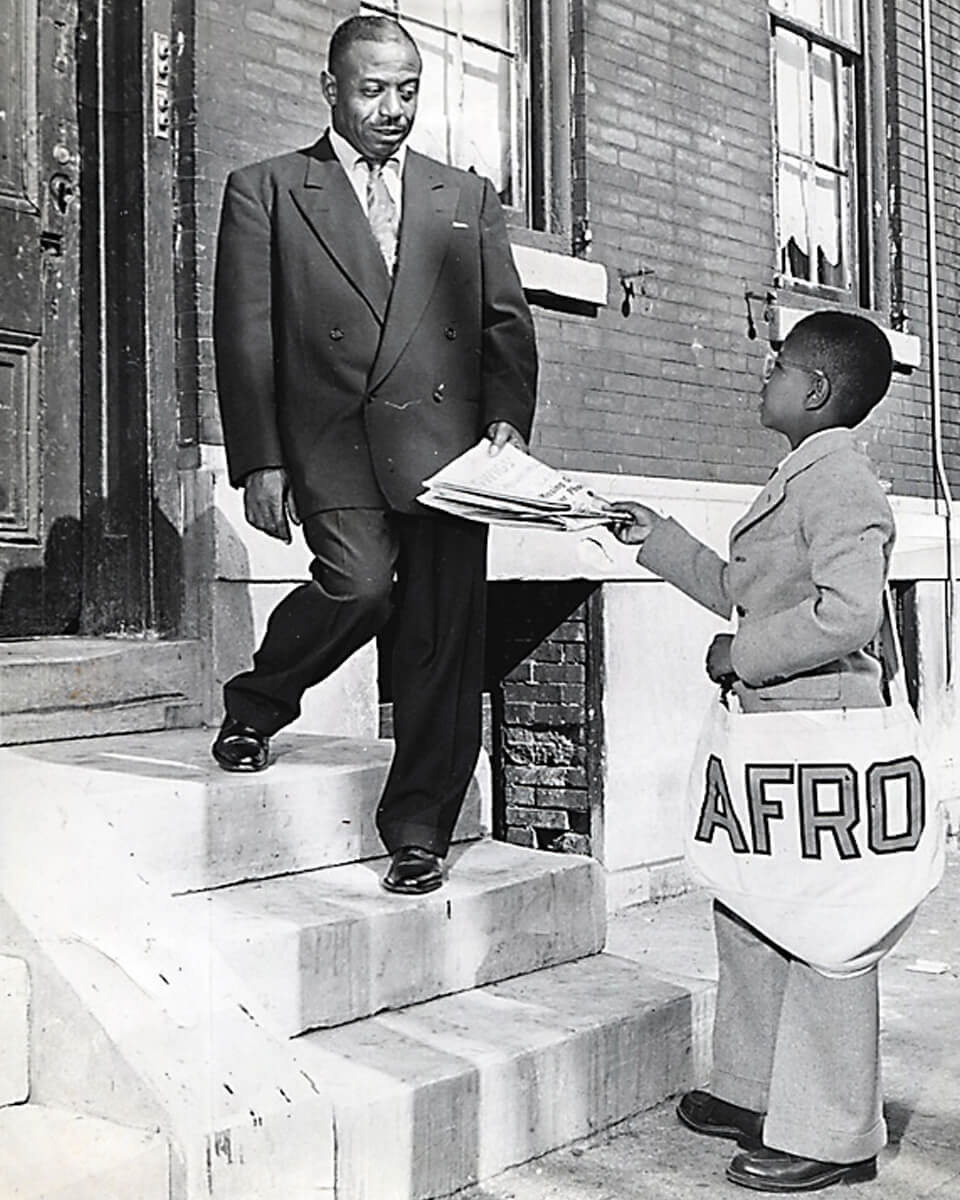

LEADING AfRICAN-American NEWSPAPER

REPRINTED WITH PERMISSION OF THE BALTIMORE AFRO-AMERICAN NEWSPAPER

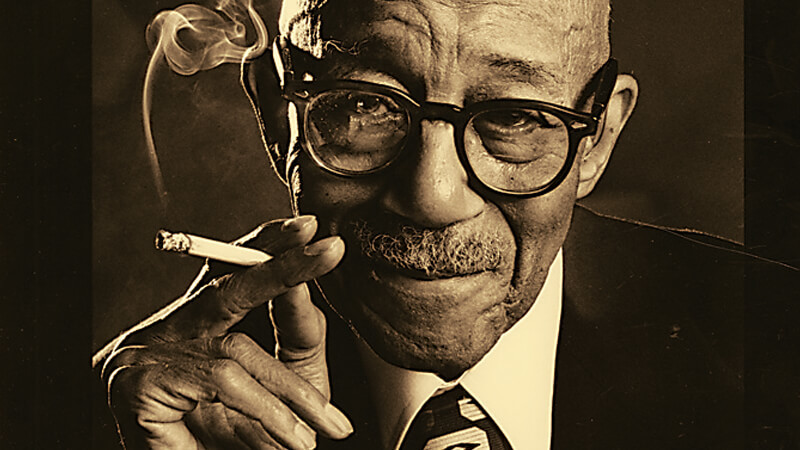

John Henry Murphy Sr., founder of one of the oldest African-American newspapers, was born into slavery in Baltimore on Christmas Day, 1840. After rising to the rank of sergeant in the U.S. Colored Troops during the Civil War, he worked as a porter, janitor, and postal clerk before merging two church publications and a third publication into the Afro-American, which celebrates its 125th anniversary this year. In its pages, The Afro fought against Jim Crow laws, including pushing for the hiring of black Baltimoreans into the city’s police and fire departments. Murphy’s son, Carl, expanded the paper into 13 major cities at its peak.

35.

LAUNCH OF WWII Liberty Ships

Permission granted from The Baltimore Sun. All rights reserved.

On Jan. 3, 1941, with the world engulfed in a second global war and America on the precipice of entering the fray, President Franklin Roosevelt announced an emergency, $350-million shipbuilding program. The S.S. Patrick Henry, the first of these ships, was launched with great fanfare on Liberty Fleet Day in September 1941. Ultimately, 384 Liberty ships and 94 leaner, faster Victory ships were built at Bethlehem Steel’s Fairfield shipyard, which made more vessels than any U.S. shipyard. By late 1943, the shipyard employed some 46,700 workers, including 6,000 African Americans, who worked around the clock, according to The Baltimore Sun. Two-hundred of the massive Liberty ships, which could carry the same amount of cargo as 300 railroad boxcars, and 500 soldiers were lost during the war, but the S.S. John Brown, also built in Baltimore, survives to this day. Usually docked in New York for educational tours, the ship occasionally sits at its birthplace, with tours scheduled here for 2017.

36.

BOXING CHAMP JOE GANS

The now obscure Joe Gans held the World Lightweight title from 1902 to 1908 and was named by The Ring magazine as the greatest lightweight pugilist in the history of the sweet science. A gentleman known as “the Old Master,” Gans was most likely born in Baltimore a decade after emancipation and is buried at Mount Auburn cemetery near Westport. After one of his titles, he told his manager that he would trade it all “for a white boy’s chance in the world.”

37.

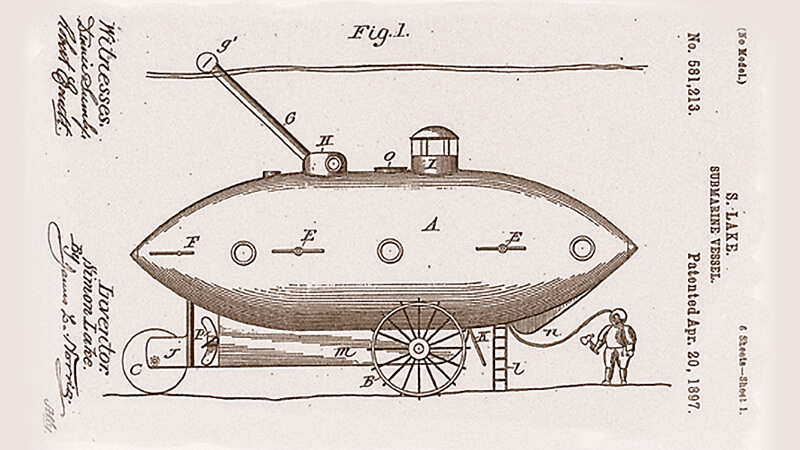

First Practical Submarine

On Dec. 17, 1897, in the cold waters off Locust Point, Simon Lake—an inventor inspired by an underwater boat in Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, which he’d read as a teenager—launched the Argonaut, the first practical submarine. Thirty-six feet long and weighing 75 tons, the vessel's 30-horsepower engine was built by Baltimore’s White and Middleton Gas Engine Company, which became a pioneer in submarine technology. After initial struggles during its maiden voyage, Lake’s Argonaut eventually submerged, making its way around Fort McHenry and Curtis Bay. Among the city officials and observers on hand was a Baltimore Sun reporter, whose editor gave the following instructions: “If Lake succeeds, give him a column. If he fails, he gets an obituary.”

38.

WWII B-26 Bombers

After forming an airplane-manufacturing company in 1912, aviation pioneer Glenn L. Martin set up shop in Middle River, producing the MB-1 bomber in the waning days of World War I. His company later built the B-26 Marauder and “Baltimore” and “Maryland” light bombers used by not just us, but also the British Royal Air Force in World War II. The factory remains as part of Lockheed Martin, as do the bungalows first built for factory workers, on streets with names like Fuselage Avenue.

39.

First PUBLICLY FUNDED GIRLS HIGH SCHOOL

In 1844, Baltimore’s Eastern High School and Western High School became the first publicly supported secondary schools for girls, setting a precedent in education equality that would take years for the entire nation to follow. At Western, located on Falls Road near Cold Spring Lane, the first class included 36 female students taught by a lone male teacher who doubled as the headmaster. Courses included grammar, rhetoric, elocution, moral philosophy, ancient history, astronomy, and botany. Eastern took an equally revolutionary, albeit less stable road, hopping from Jonestown to North Avenue before settling on 33rd Street in Waverly, where it eventually went coed, then shuttered in 1986. Western still stands, however, as the oldest public all-girls high school in the U.S.

40.

FIRST MAJOR AMERICAN ORCHESTRA

SUPPORTED BY PUBLIC FUNDS

Permission granted from The Baltimore Sun. All rights reserved.

Ever wonder why the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra is so beloved? It might have something to do with its origins. Founded in 1916, the BSO was the first major orchestra in the country fully funded by public money. The orchestra went private in 1942, but its strong bond with the city had been forged. And the BSO has built upon those forward-thinking roots, naming maestro Marin Alsop music director in 2007, making her the first woman to lead a major American symphony.

41.

Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty

One of a handful of Americans born into slavery to document his world-view, Baltimore Rev. Harvey Johnson founded the Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty—the forerunner of the Niagara Movement and the NAACP. After ejection from a B&O train for refusing to sit in a segregated compartment on his way to a Niagara meeting in Harpers Ferry in 1906, Johnson went on to fight and overturned Maryland’s separate car rules for interstate passengers—six decades before the famous Freedom Riders. Union Baptist, the historic church he led, thrives to this day on Druid Hill Avenue.

42.

JAZZ LEGEND EUBIE BLAKE

COURTESY OF the maryland historical society, PP301.442

Blake was born James Hubert Blake at 319 Forest St. in Baltimore, and grew up with the sounds of ragtime. A whiz on the piano, he used those syncopated rhythms as inspiration for the popular songs he wrote, particularly when he joined forces with Noble Sissle. The pair performed in vaudeville and, most notably, wrote the music and lyrics for Shuffle Along, which, when it opened in 1921 at the Sixty-Third Street Music Hall in New York, changed musical theater. It was one of the first musicals to be written by African Americans and to feature a black cast (including a young Josephine Baker), which was remarkable since African Americans were banned from performing onstage in front of whites for much of the 19th century. Shuffle Along became a huge hit and did much to further the presence of African Americans in theater. Blake lived to be 100 years old. Casts of his hands are part of the permanent collection at the newly opened National Museum of African-American History and Culture at the Smithsonian.

43.

FIRST CATHOLIC BASILICA

BUILT IN BALTIMORE IN 1806

MIKE MORGAN

The cradle of American Catholicism, in a former colony founded by the Calvert family for religious freedom, Baltimore was home to the first Roman Catholic diocese in the United States, established in 1789. By the early 19th century, the diocese, ruled by the Jesuit Archbishop John Carroll, stretched from the Chesapeake to the edge of the Idaho territory and down to New Orleans after the Louisiana Purchase. The list of Catholic “firsts” that occurred in Baltimore—particularly landmark dates in African-American history—are enough to fill a church bulletin: first Catholic seminary, St. Mary’s, established 1791 on Pennsylvania Avenue near Paca Street; first black parish, St. Francis Xavier, established 1793; first Catholic school for black children, St. Frances Academy, 1828, still in operation on East Chase Street; first order of African-American Catholic nuns, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, founded 1829 by Haitian immigrant Mother Mary Lange; first African-American ordained Catholic priest, the Rev. Charles Uncles, 1891; first Roman Catholic college for women, the College of Notre Dame, chartered in 1896 and now a university. And, of course, the first Catholic cathedral in the United States, the Basilica of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, cornerstone laid July 7, 1806.

44.

BILLIE Holiday SINGS THE BLUES

Few have a more iconic voice than Lady Day. And her decision to record the song “Strange Fruit” in 1939—which called attention to the scourge of lynchings in the U.S.—contributed to the dawning of social activism in jazz music. Holiday spent part of her formative childhood in Fells Point, and worked here as an errand girl at a brothel. She moved to New York in 1928 and soon began singing in nightclubs (famously returning to Baltimore’s Royal Theatre), gaining acclaim when she became the vocalist in Artie Shaw’s band. Her recordings are still considered gold standards of the American jazz scene.

45.

BANDLEADER CAB CALLOWAY

The legendary “Hi-De-Ho Man” and big band leader grew up in West Baltimore’s Sugar Hill neighborhood, following in the footsteps of Eubie Blake in Frederick Douglass High School’s revered music program. He later got his start in the famed clubs of nearby Pennsylvania Avenue, including the Royal and Regent theaters.

46.

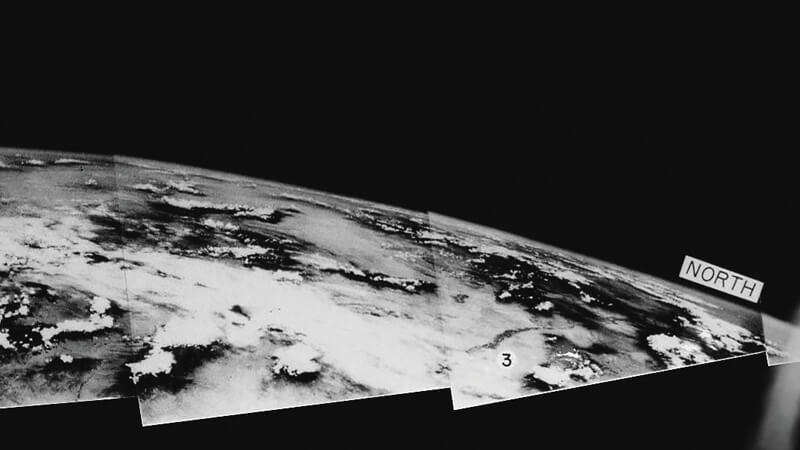

FIRST PHOTO OF EARTH FROM SPACE

NASA

On Oct. 24, 1946, a missile with a 35-mm camera designed by Clyde Holliday of the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory hurtled upward to an unprecedented height of 65 miles above Earth. When recovered, the grainy, black-and-white images revealed a cloud-swirled segment of the planet set against the inky blackness of space. We could, for the first time, see “how our Earth would look to visitors from another planet coming in on a space ship,” Holliday later wrote in National Geographic. The experiment laid the groundwork for missile surveillance and mapping, weather satellite imaging, and, of course, the space program.

47.

FIRST DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL CONVENTION

The first-ever Democratic National Convention took place in Baltimore from May 21-23, 1832. During the party’s confab, delegates selected Martin Van Buren as the running mate for then-incumbent president (and party founder) Andrew Jackson. The Jackson-Van Buren ticket won in a landslide, ushering in Jackson’s second term and setting the stage for Van Buren’s subsequent presidency.

48.

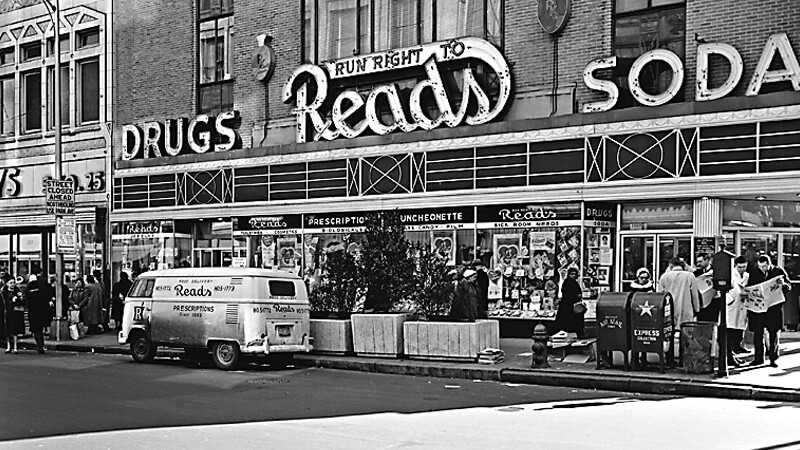

FIRST SUCCESSFUL LUNCH COUNTER SIT-IN

the BGE Photo Collection, Baltimore Museum of Industry;

Sixty-two years ago this month, Morgan State student Helena Hicks and several friends ducked inside segregated Read’s Drugstore in the Howard Street shopping district on a blustery morning. “Let’s go inside, all they are going to do is tell us to leave,” Hicks told her friends. That small act of defiance—on the heels of others by Morgan students—caught the attention of The Afro-American, sparking a change in Read’s lunch-counter policy.

49.

The Jackson-MITCHELL FAMILY

ALAMY

The history of the NAACP and the civil rights movement in both Maryland and the U.S. is inseparable from the story of Baltimore’s leading civil rights family. From 1935 through the 1960s, Lillie May Carroll Jackson led the NAACP’s Baltimore chapter, which initiated precedent-setting legal challenges of segregation. Her Bolton Hill home serves as a civil rights museum today. Her daughter, Juanita Jackson Mitchell, was the NAACP’s first national youth director and later, the first black woman to practice law in the state. She succeeded her mother as president of the NAACP Baltimore branch. Her husband, Clarence M. Mitchell Jr., whom the city courthouse is named for, became known as “the 101st U.S. Senator” on Capitol Hill during his relentless campaign to win passage of the Civil Rights, Voting Rights, and Fair Housing acts.

50.

FIRST U.S. manned BALLOON LAUNCH

The first manned American aircraft flight is credited to 13-year-old Edward Warren in 1784—119 years before the Wright Brothers took flight. In lieu of the balloon’s 234-pound inventor, Warren volunteered his services before a large Howard Park crowd. According to accounts, the lad “behaved with the steady fortitude of an old voyager” as he “soared aloft,” acknowledging by a “significant wave of his hat” the cheers of those gathered below.

51.

FIRST modern medical school

COURTESY OF The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

After his death in 1873, Quaker merchant Johns Hopkins left a $7 million bequest to establish a university and hospital in Baltimore. Hopkins’ first president, Daniel Coit Gilman, and the school’s trustees envisioned a medical school in a European model of training, emphasizing graduate education and research. The centerpiece of the medical school was a state-of-the-art hospital that opened in 1889, with a powerhouse faculty of some of the best and brightest medical practitioners of the era. Over the decades since, Hopkins doctors developed the “blue baby” surgery, the field of neurosurgery, the use of latex gloves in surgery, implantable defibrillators, and countless other innovations.

52.

FIRST General meeting of the quakers

You probably remember learning about George Fox in grade-school history. Known for his dissent of the Church of England, Fox began spreading his message of spiritual individualism in the 1640s. By the mid-seventeenth century, his teachings made their way to America, and in 1785, the first Quaker Yearly Meeting was held in Charm City. The local gathering, which led to a regional arm of the Religious Society of Friends, drew Quakers from Northern Virginia, Western Maryland, and parts of Pennsylvania. Still active today, the Baltimore chapter offers a wide range of programs for the Quaker community, including summer camps and women’s retreats.

53.

First U.S. ordained rabbi

The Baltimore Hebrew Congregation first convened above a Fells Point grocery. The synagogue was revolutionized when German-born Rabbi Abraham Rice, the first ordained rabbi in the country, joined in 1840. Rice strengthened Baltimore’s knowledge of Orthodox Judaism and established the community’s first Hebrew schools.

54.

Irene Morgan REBELS

In July 1944, more than a decade before Rosa Parks, Irene Morgan, a 27-year-old mother of two, was dragged from a Greyhound bus, arrested, and convicted after refusing to give up her seat to a white couple during a ride through Virginia, where she been recuperating from a miscarriage at her mother’s home. Unlike Parks, she had no civil rights training, but pled not guilty to violating the state’s segregation law. Appealing her 1944 conviction with the help of NAACP lawyers, including fellow Baltimorean Thurgood Marshall, she broke down a key constitutional interstate segregation law in her landmark Supreme Court case, Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia.

55.

THEODORE WOODWARD CURES TYPHUS

The enemy in WWII wasn’t just global fascism, but also infectious diseases that decimated U.S. troops. The University of Maryland’s Theodore Woodward helped cure typhus, tularemia, cholera, and other diseases. Among the honors bestowed upon “one of the fathers of the subspecialty of infectious disease” was a nomination for the Nobel Prize.

How Well Do You Know

Your Baltimore History?

56.

FIRST AMERICAN Methodist Church

MIKE MORGAN

In 1784, representatives from scattered Methodist congregations came to Baltimore’s Lovely Lane Meeting House for a historic Christmas conference where they organized the First Methodist Episcopal Church. Today, the Lovely Lane church on St. Paul Street is known for the heavenly mural in the elliptical dome above its sanctuary and, more importantly, as “the mother church of American Methodism.”

57.

FATHER OF PHILANTHROPY

Born to modest means, George Peabody came to Baltimore after serving in the War of 1812, prospering as a wholesale-goods merchant. Over his two decades in Baltimore, he transformed himself into an international banker and financier before moving to London, but never forgot the privations of his youth and lack of a formal education. Peabody gave away an estimated half of his $16 million fortune during his lifetime, becoming known as “the father of modern philanthropy.” He’s credited with influencing Johns Hopkins and Andrew Carnegie as well as later generations of philanthropists. In 1857, he founded the Peabody Institute of Baltimore, including the music conservatory and public library. After the Civil War, Peabody endowed the Peabody Education Fund with $2 million to build public schools and train teachers in the South.

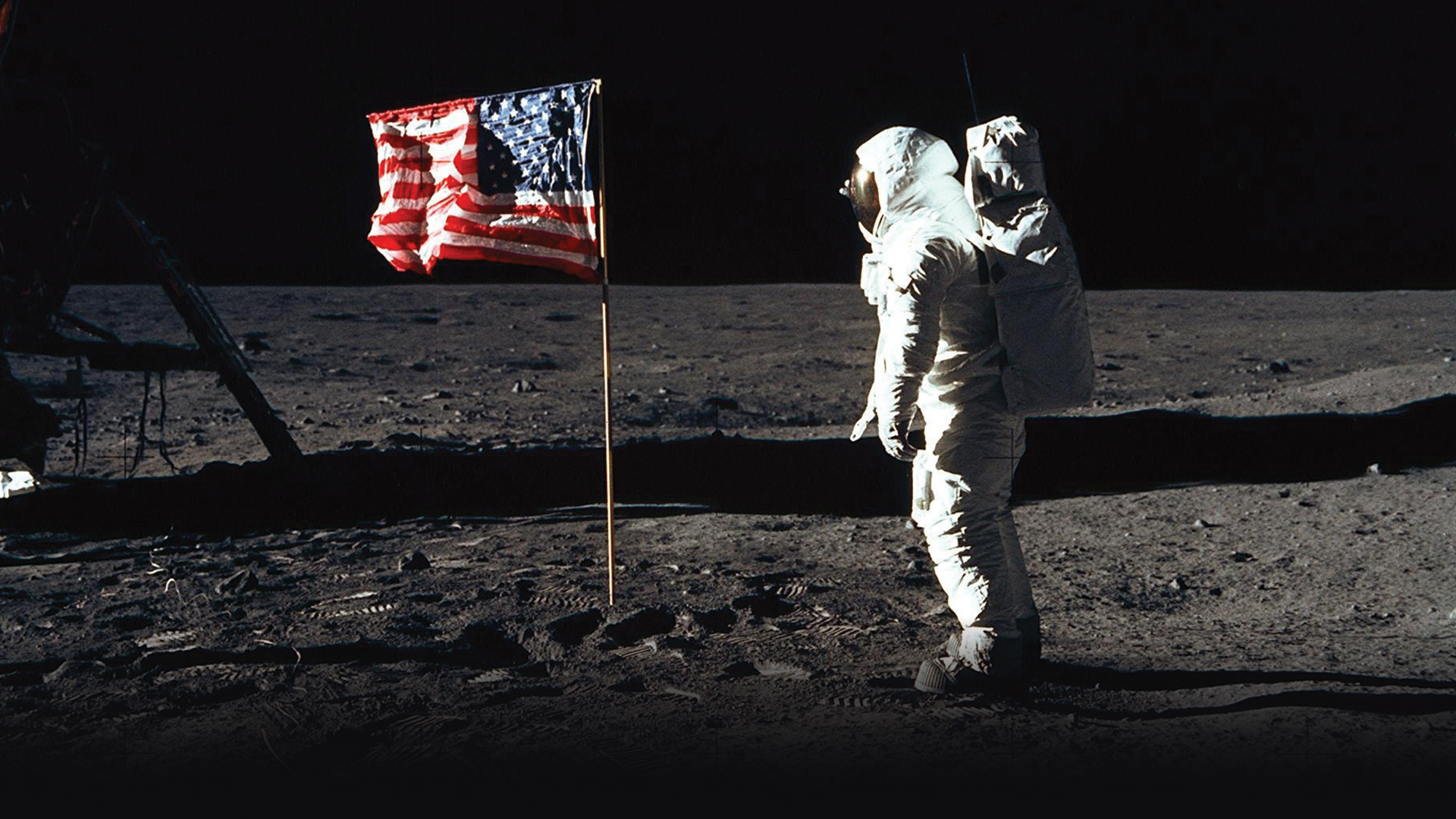

Courtesy of NASA

58.

IMAGES OF MAN’S FIRST WALK ON THE MOON

How were 500 million people around the world able to watch Neil Armstrong’s “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind”? With a seven-pound, black-and-white camera built in Linthicum. The camera was developed for NASA’s 1969 Apollo 11 mission by engineer Stanley Lebar at what was then a Westinghouse plant (now Northrop Grumman). It was no mean feat. The camera needed to be able to endure the rigors of space travel, including the velocity of liftoff and temperature swings from -250 to 300 degrees Fahrenheit, and it had to operate in low light conditions. That Lebar and his team were able to do all this is Baltimore’s small but significant contribution to mankind’s giant leap.

59.

First ymca BUILDING

COURTESY OF the maryland historical society, 1994.42.013

In reaction to unhealthy social conditions arising during the Industrial Revolution in London, the Young Men’s Christian Association was started in 1844. The first YMCA chapter in the U.S. was formed in a Boston church in 1851, but the first building erected specifically as a YMCA was built at the corner of Pratt and Schroeder near Union Square in Baltimore.

60.

First Department of Public Health

Public health —i.e., “the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health . . . through organized community efforts”—has been practiced in some form or another since antiquity. But Baltimore introduced it to America in 1793 when the governor of Maryland assigned the city’s first health officers to respond to an outbreak of yellow fever in Fells Point. Since then, the department has only grown, and it’s now an 800-employee-strong division of city government with purview over everything from restaurant inspections and animal control to HIV/STD testing and maternal and infant health. Throughout its 223-year history, the department has sometimes embraced controversial treatments and practices, such as handing out long-term birth control in schools or issuing a blanket prescription for the opioid overdose prevention drug naloxone. But these bold moves have only earned it a reputation as a haven for innovative, ambitious public health professionals. That legacy of innovation continues now under Dr. Leana Wen, who was just 32 years old when she became health commissioner in January 2015.

61.

OLDEST JEWISH COMMUNITY CENTER

Tracing its history to the Hebrew Young Men’s Literary Association, founded in 1854, and later other local Jewish organizations, the Jewish Community Center in Baltimore is North America’s oldest. With 50,000 Eastern European Jewish immigrants streaming into Baltimore at the turn of the century, the Jewish groups that eventually merged into the current JCC offered citizenship classes, religious school, clubs, and, of course, dances and basketball.

GETTY IMAGES

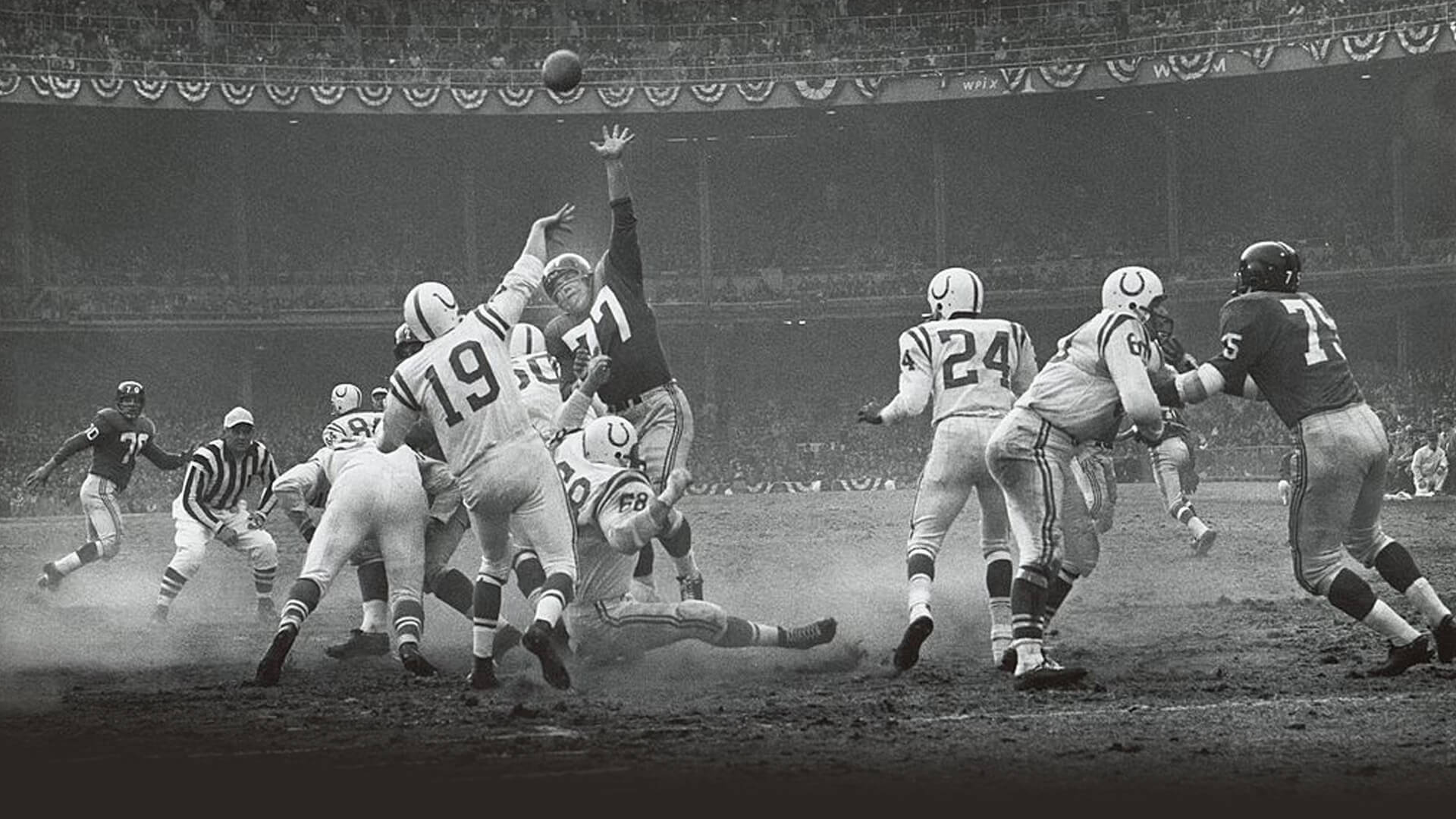

62.

The greatest game ever PLAYED

The title game between the New York Giants and the Baltimore Colts, featuring 17 future Hall of Famers, at Yankee Stadium on Dec. 28, 1958, established the National Football League as a television powerhouse and launched the gridiron’s dominance over baseball as the pastime Americans loved best. Baltimore won 23-17 in overtime when fullback Alan Ameche crossed the goal line on a 1-yard run. Johnny Unitas, who led the Colts on a dramatic 86-yard, game-tying drive at the end of regulation, emerged from the contest as the sport’s premier quarterback. Every autumn for the next decade, zealous Colts fans would turn Memorial Stadium into “the world’s largest outdoor insane asylum.”

63.

Rachel Carson ENVIRONMENTAL STEWARDSHIP

One of our country’s earliest environmentalists, Rachel Carson spent her formative years of zoology graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University, helping pave the way for her now classic 1962 call to arms, Silent Spring. Across 400 pages, the former Baltimore Sun contributor (often writing about the Chesapeake Bay) linked chemical pesticides to harmful effects on wildlife, pets, and even humans, igniting a backlash, but eventually leading to the ban of DDT. Two years later, Carson passed away in her home in Silver Spring—her legacy has only grown since.

64.

FIRST U.S. SHOCK TRAUMA CENTER

In the 1960s and ’70s, former military surgeon R Adams Cowley, who coined the term “golden hour,” began advocating against the principle of “nearest hospital first” and for the speedy transport of victims with life-threatening injuries to specialized trauma centers. Cowley founded the shock trauma center and America’s first statewide trauma system.

65.

PIMLICO AND PREAKNESS

With origins that date back to the 1660s, the Pimlico neighborhood (and thus racecourse) was named by English settlers who were paying homage to Olde Ben Pimlico’s Tavern in London. The track officially opened in the fall of 1870 when the colt Preakness won the Dinner Party Stakes. Three years later, the thoroughbred race would be inaugurated in his honor. Pimlico has seen many special moments throughout the years, including the match race Seabiscuit won in 1938, the epic comeback of Secretariat in 1973, and most recently the Triple Crown win of American Pharoah in 2015. After all, there would be no Triple Crown if it weren’t for the middle jewel.

66.

First Professional Sports CLUB

Years before the Revolutionary War, George Washington enjoyed watching the racing thoroughbreds of the Maryland Jockey Club. Dubbed the oldest sports franchise in the country, the institution was established in Annapolis in 1743—the same year that the Annapolis Subscription Plate, the first recorded formal horse race in Colonial Maryland, was run and its silver trophy awarded. It is believed to be the second-oldest horse racing trophy in the U.S. The Maryland Jockey Club later moved to Pimlico Racecourse, where the Preakness Stakes began in 1873.

67.

First unitarian church

Founded on the principles of tolerance and social justice, the roots of the American Unitarian tradition can be traced to Mount Vernon’s First Unitarian Church—a National Historic Landmark. On May 5, 1819, the Rev. William Ellery Channing delivered his landmark “Baltimore Sermon” at the ordination of the church’s first minister, Jared Sparks. Preaching about a God who “is infinitely good, kind, benevolent” and who blessed humanity with innate goodness, rationality, and the wisdom to distinguish good and evil, Channing defined American Unitarianism, leading to the denomination’s formation in 1825.

Permission granted from The Baltimore Sun. All rights reserved.

68.

World’s biggest steel mill bethlehem steel

employed more than 40,000 workers

The story of Bethlehem Steel’s Sparrows Point works—once the largest in the world at 3,100 acres, stretching four miles from end to end—is the story of the United States. From the end of our agrarian society (steel was first produced there in 1889) through a loss of manufacturing so dire that developers had to import steel to turn the original Bethlehem plant in Pennsylvania into a casino, Baltimore’s fortunes followed those of Sparrows Point. Male or female, black or white, immigrant or native, if you worked “down the Point” you had working class status in Baltimore equal to just about any white-collar job. In 1959, the combined employment of the mill and the shipyard was more than 40,000, with the plant serviced by four railroads and miles of piers for the docking of ore ships. The mill’s steel ended up in girders for the Golden Gate and Chesapeake Bay bridges, cables for the George Washington Bridge, and support for the Empire State Building. Despite frequent layoffs as American manufacturing jobs increasingly went overseas, Sparrows Point workers were able to buy homes, take the family down the ocean every summer, and—when work was steady—have some pocket money left over. Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy in 2001.

69.

First store-bought antacid

GETTY IMAGES

druggist Isaac E. Emerson moved from the Carolinas to Baltimore in 1881, carrying a recipe for an effervescent headache and stomach potion, then marketed it as Bromo-Seltzer, the first store-bought antacid. He got filthy rich from people with food poisoning and hangovers, but still found time to serve in the Navy in the Spanish-American War, organizing private yachts to patrol the East Coast and earning the title of “Captain Emerson.” In 1911, after a trip to Italy, he built the vaguely tacky Bromo-Seltzer Tower, mimicking Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio Tower. (It once had a 17-ton, rotating blue Bromo-Seltzer bottle on top lighted by 596 bulbs.) And he owned fancy hotels and a casino. A-list party guest, right?

70.

Barbara mikulski takes her

place in the u.s. senate

When the daughter of Polish grocers won election to Congress’ upper house in 1986, there had never been a Democratic woman elected to the Senate who wasn’t appointed or succeeding her deceased husband. The former social worker had launched her political career fighting against an urban highway, and her entrance into the boys club didn’t just mark progress for the women’s movement but also for grassroots organizing. She authored the first legislation President Obama chose to sign into law, the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. Later, when Obama presented her with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015, he described Mikulski as a “lioness” on Capitol Hill. By the time she announced that she was retiring this month, she’d become the first woman to serve as chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee and the longest-serving female member of Congress ever.

71.

NatTY boh invents the six-pack

DAVID COLWELL

You can carry a lot more beer home from the liquor store thanks to National Bohemian, which, in 1943, became the first beer producer to sell its products in six-packs. Ain’t the beer cold!

72.

PIKESVILLE Rye WHISKEY

In the late 18th century, farmers in Maryland and Pennsylvania were planting plenty of rye as cover crops, when they realized it was cheaper (and pretty delicious) to distill the stuff. Pikesville Rye came along in 1895, thriving until the booming Maryland rye industry was halted by Prohibition—and reemerging in 1936 when Standard Distillers began bottling it on Lombard and Commerce streets. More recently, local brands like Sagamore and Lyon have revived Maryland’s tradition.

73.

Men’s Garment Capital

The men’s garment industry in Baltimore got its start making uniforms for Civil War soldiers. “It wasn’t a big leap from making uniforms to men’s suits,” says James Keffer of the Baltimore Museum of Industry. “New York was the women’s garment capital, but Baltimore was the men’s garment capital from the Civil War until the 1930s.”

74.

FIRST u.s. umbrella factory

If the Chinese want more credit for stuff, we’ll give them the invention of the umbrella. But it was Charm City that brought mass production to the rainy-day essential: William Beehler’s eponymous company was the largest manufacturer in the nation in the mid-1800s. Earning us the title of the “umbrella capital of the world,” the company made more than two million umbrellas a year at its peak, until the introduction of automobiles and trolleys hurt sales, protecting more people from the elements. Advertising slogans were a must back then, too. And one of the most memorable— “Born in Baltimore, raised everywhere”—came from one of Beehler's top Charm City competitors: Gans Brothers.

75.

Emily post etiquette

“You know I am by birth and in heart a Baltimorean.” The 1872-born etiquette maven first grew up in the Mount Vernon neighborhood—her father was a prominent architect—and she was home schooled in her early years before moving to New York in 1878. Another fun fact about Post—she was actually credited for loosening and simplifying snobbish rules of etiquette. That’s so Baltimore.

76.

Henrietta lacks and Hela cells

In 1951, a poor, black tobacco farmer from Virginia came to Johns Hopkins for treatment, and unknowingly had her cells taken from her. Though that tobacco farmer died a short time later, her cells lived on, becoming one of the most important tools in medicine—they were involved in developing the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, and in vitro fertilization. The story of Henrietta Lacks and her cells, which brought up probing questions about medical ethics and the history of medical experimentation on African Americans, finally came to the public’s attention as the subject of the 2010 New York Times bestseller The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, which is being adapted for HBO by Oprah Winfrey.

77.

First portable drill is

created BY black & decker

Owners of a small machine shop in 1910, Duncan Black and Alonzo Decker were working on a Colt Arms Company project when inspiration struck. Their innovative pistol grip and trigger design introduced power tool portability and later, NASA partnered with Baltimore’s Black & Decker to develop the necessary cordless drills to take into space.

78.

First Female Speaker of the House

GETTY IMAGES

Born in 1940 into local political royalty—dad Thomas Jr. and brother Thomas III had both served as mayor—Nancy Patricia Pelosi (née D’Alesandro) went into the family business after marrying Paul Pelosi and moving to San Francisco. In 1987, she became a member of the House of Representatives and, in 2007, she did her family and Baltimore proud by becoming the first female (and Italian-American!) speaker of the House.

79.

First U.S. olympic hero

Arguably the most exciting moment in the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 came from Robert Garrett of the great Baltimore railroading family, who had taken up the discus for the very first time. Knowing little about the sport, Garrett practiced at home with a blacksmith-made discus that was nearly 20 pounds—only realizing the regulation discus was just 4.4 pounds when he arrived in Athens. Trying to adjust his motion, speed, and release, Garrett’s first two throws flew wildly off course. But his third and final attempt soared straight and true, besting his Greek opponent by more than 7 inches. While he was the first, Garrett certainly wasn’t the last Baltimorean to produce magical moments at the Olympics—Michael Phelps, of course, has won more gold medals than any athlete in history.

80.

Oldest Silversmith

Courtesy of the BGE Photograph Collection, Baltimore Museum of Industry

Founded in 1815 and famous for its manufacturing of exquisite silver products, hand-chasing, and repoussé work, Samuel Kirk & Son (renamed Kirk-Stieff Company after a merger with The Stieff Company) was the oldest continually operating silversmith in the United States when it closed its doors in 1999. To this day, collectors including the White House, which commissioned silver during the Cleveland and Eisenhower administrations, covet Kirk- Stieff silver.

81.

First company to PRODUCE stainless steel

During the early 1900s, metal scientists discovered that adding chromium in a batch of iron produces a durable steel resistant to rust and corrosion. “Stainless” steel, however, remained a costly luxury item until Baltimore’s Rustless Iron & Steel Co. found an inexpensive way to mass produce the alloy, making it affordable for the country’s growing middle class.

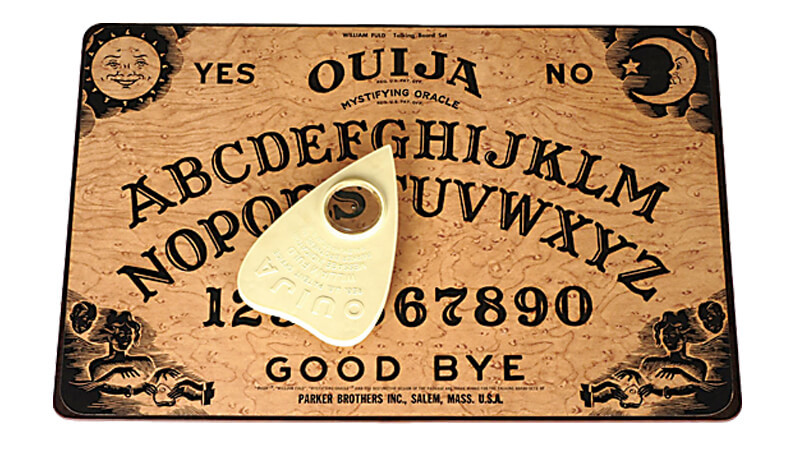

82.

OUIJA BOARD INVENTED HERE

In the 19th century, modern medicine still had a long way to go and Americans had a closer relationship to death. It’s in that context that entrepreneur Charles Kennard, coffin maker E.C. Reiche, Baltimore lawyer Elijah Bond, and Bond’s sister-in-law, Helen Peters—who claimed spiritual gifts—combined to create the Ouija, a “talking board” that served as a channel to the dead and somehow won a U.S. patent in 1890.

83.

Upton Sinclair

“[Druid Hill] is such a beautiful park,” Upton Sinclair once recounted. “I used to walk over from Grandfather Harden’s house on Maryland Avenue with a book of Shakespeare under my arm.” Author of meatpacking industry exposé The Jungle, and a Pulitzer Prize winner for his novel on the Nazi takeover of Germany, Sinclair’s humanistic values were shaped by the juxtaposition of his father’s poverty and his maternal grandparents’ wealth.

84.

The cone sisters bring back paris

the baltimore museum of art

Etta and Claribel Cone first collected art to decorate their Baltimore home. But while on trips to Paris, they visited Gertrude Stein—who Claribel knew from their days at the Women’s Medical College at Johns Hopkins—and she introduced them to a cadre of artists, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso among them. The sisters were drawn to the brilliant color and groundbreaking style of these modern masters, and when they returned home laden with paintings, sculptures, and drawings, they were doing more than increasing their art collection—they were bringing modern art to America. Matisse, in particular, inspired the Cones (he affectionately called them “my Baltimore ladies”) and in total, they accumulated roughly 500 of his works, which are considered the largest collection of his art in the world. Upon Etta’s death, their 3,000-object collection was left to the Baltimore Museum of Art, where, as Claribel said, “the spirit of appreciation for modern art in Baltimore became improved.”

85.

HARD-BOILED DETECTIVES

The writer of The Maltese Falcon and The Thin Man, Dashiell Hammett dropped out of Baltimore’s Polytechnic Institute at 14, working odd jobs before landing a gig with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, an experience that formed the basis of his noir career. Always an avid reader, and with a hard-drinking education from the streets, he initially resumed his detective career after contracting tuberculosis during World War I. He later trained as a reporter and wrote his first pulp magazine stories to make ends meet.

86.

H.L. Mencken: THE SAGE OF Baltimore

getty images

No one can deny that Henry Louis Mencken had a true gift for criticism and satire, documented in his legendary columns in The Sun. As Jonathan Yardley noted in his review of a 2002 Mencken biography, “Nobody else could make so many people so angry, or make so many others laugh so hard.” Working at a time when writers like F. Scott Fitzgerald also found inspiration here, the Sage of Baltimore, as Mencken would come to be known, also had a sociological interest in phraseology that was unique to the United States, and in 1919 he published his book The American Language, which explored the differences between British and American English. At the time, it was the most scientific work on the American language, and it continues to serve as a definitive resource.

87.

First Shopping center AT ROLAND PARK

Designed by the esteemed Baltimore firm of Wyatt & Nolting and built in 1895, the Tudor-style Roland Park Shopping Center at Upland Road and Roland Avenue was the first of its kind in the country. With its string of stores and off-street parking, the shopping strip catered to the residents of one of America’s first “garden suburbs” who needed a place to shop—and park—outside of the city center. Innovative for its time, it featured a doctor’s and dentist’s office on the second floor and essential shops like Morgan Millard (aka “The Morgue”), a popular drugstore and luncheonette on the ground floor—now the site of Petit Louis Bistro.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

88.

ROSIE THE RIVETERS GO TO WORK IN

BALTIMORE’S WWII FACTORIES

Maryland has its own chapter of the American Rosie the Riveter Association, and nowhere were women more critical than in the WWII-era steel plants, shipyards, and aircraft factories of Baltimore. A can-do woman in a denim work shirt flexing her bicep and sporting a red headscarf, presumably to keep the sweat of factory work out of her eyes, wasn’t exactly the 1940s stereotype of American femininity. But young women from Appalachia, the Carolinas, and Baltimore, of course, responded to home-front labor shortages during the early days of the war, as men flocked to join the military. One of the pitches of the federal government’s Rosie the Riveter-recruitment initiative: “The more women at work, the sooner we win.”

89.

FIRST MODERN Gas PUMP

Pittsburgh claims to be home to the first drive-in filling station in 1913, but it was nothing like a gas station today—the modern gas pump hadn’t even been invented. Louis Blaustein, a Lithuanian Jew who had immigrated to the U.S. as a teenager and first worked as a peddler, founded the American Oil Company (Amoco) in June of 1910, making deliveries on the unpaved streets of Baltimore with one horse and a 270-gallon kerosene tank wagon. Among the accomplishments credited to Blaustein and his family-run business—his son, Jacob, was a chemist—are “no-knock” gasoline, the first gas pump to show the driver the amount of fuel being purchased, and the first modern, company-owned gas station, located on Cathedral Street. Charles Lindbergh chose Amoco fuel for his famous 1927 flight from New York to Paris.

90.

Sweetheart cup CoMPANY

First founded as an ice-cream-cone bakery in 1911 in Owings Mills, the Sweetheart Cup Company began producing paper cups after World War II. If you’ve ever sipped out of something that wasn’t glass or clay, odds are it was made by Sweetheart—or Solo Cup, which purchased the company in 2004.

91.

ICONIC GLOBE POSTERS

COURTESY OF GLOBE COLLECTION AND PRESS AT MICA

Musicians knew they’d made it when Globe Poster printed their playbill. Beginning in 1929, Globe created iconic, colorful posters for movie theaters, burlesque shows, drag races—but most influentially for R&B, soul, and jazz performances featuring the likes of Tina Turner and James Brown. Globe closed its doors in 2010 but, thankfully, the Maryland Institute College of Art acquired more than 75 percent of the company’s collection of wood type, letterpress “cuts,” and original posters so its iconic look will live on in the work of students.

92.

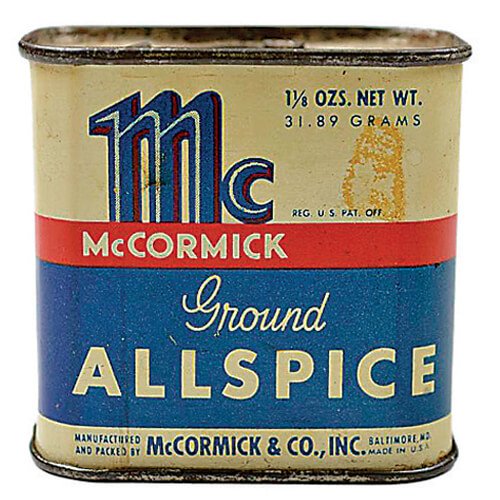

THE MCCORMICK SPICE COMPANY

Since 1889, McCormick & Company—founded by Willoughby M. McCormick, who started the business in Baltimore at age 25 from a cellar—has dominated the industry. After surviving the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, when all assets and records were lost, the business (now headquartered in Glencoe) rakes in $4.3 billion in sales annually and reaches consumers in more than 140 countries and territories thanks to its line of more than 650 spices, herbs, seasonings (including, of course, beloved Old Bay), extracts, and other products. Little known fact: McCormick was also among the first producers of gauze tea bags back in 1910.

93.

TRAFFIC LIGHT innovation

Think the Falls Road and Northern Parkway intersection is one of the city’s most accident-prone? You’d be right. Ironic, then, that the first sound-actuated traffic light was installed at the then somewhat rural crossroads in 1928, the invention of Baltimorean Charles Adler Jr., who used technology he’d developed for railroad crossings. One early problem: Even mooing cows could activate it.

94.

LEXINGTON MARKET:

THE OLDEST MARKET IN AMERICA

Founded in 1782, bustling Lexington Market is thought to be the oldest marketplace in America. When writer Ralph Waldo Emerson broke bread here, he dubbed Baltimore “the gastronomic capital of the world.” With Berger cookies, crab cakes, chicken and waffles, fried okra, and sausages and subs all under one roof, it remains a gourmet go-to.

95.

The catonsville NINE PROTEST THE WAR