Business & Development

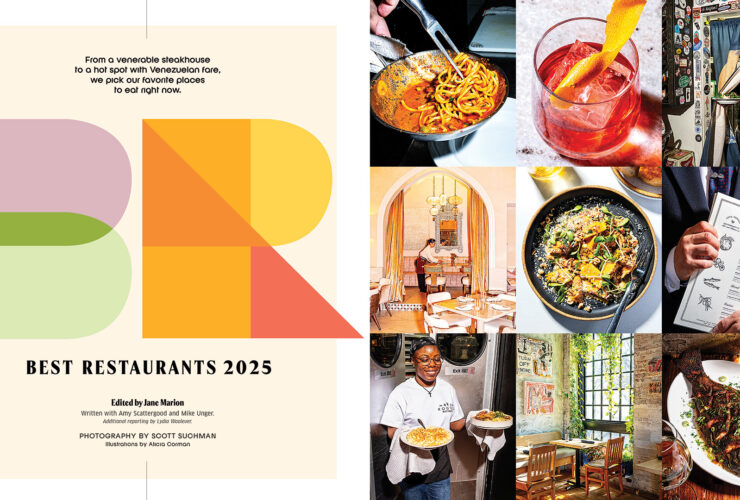

Hunger Games

With 11 restaurants and counting, Alex Smith, along with his brother Eric, is out to conquer the baltimore dining scene.

Chances are, even if you’ve only heard of Alex Smith, you have a strong sense that you don’t like him. And he’s well aware of what you think: private school lax bro, grandson of the late H&S Bakery billionaire and Harbor East developer John Paterakis Sr., and, more recently, owner of some of Baltimore’s trendiest, spendiest fine-dining restaurants, not to mention their sister spots in other states. Among them: Loch Bar, Azumi, Bygone, Ouzo Bay, Tagliata, The Elk Room, and Italian Disco (plus Harbor East Delicatessen & Pizzeria and the Häagen-Dazs in Harbor East).

Chances are, even if you’ve only heard of Alex Smith, you have a strong sense that you don’t like him. And he’s well aware of what you think: private school lax bro, grandson of the late H&S Bakery billionaire and Harbor East developer John Paterakis Sr., and, more recently, owner of some of Baltimore’s trendiest, spendiest fine-dining restaurants, not to mention their sister spots in other states. Among them: Loch Bar, Azumi, Bygone, Ouzo Bay, Tagliata, The Elk Room, and Italian Disco (plus Harbor East Delicatessen & Pizzeria and the Häagen-Dazs in Harbor East).

But here’s the thing about Smith: Your opinion of him only fuels his desire to be better. “When people don’t know me, they hate me,” Smith is the first to admit. “I’ve had people walk up to me in the restaurants and they go, ‘You’re a manager here?’ And I go, ‘Yeah.’ And they go, ‘How do you feel working for a guy like Alex Smith? I’ve met him a couple of times and the guy’s a complete jerk.’”

Smith leans in a little closer and delivers the denouement, which he does with a certain pleasure. “And then I’ll say, ‘I just want to introduce myself—my name is Alex Smith.’”

Smith is 34, and his brother Eric, a co-owner of Atlas Restaurant Group, is 28. Together, they are the youngest restaurateurs in the country to own so many high-end dining establishments. In 2017 alone, they opened four eateries. By the end of 2019—with the planned spring opening of The Choptank, a stylish crab house in the south shed of the historic Broadway Market, the summer opening of a Latin fusion restaurant on the former site of the Four Seasons’ Wit & Wisdom, as well as third locations of Loch Bar and Ouzo Bay in Houston, Texas, and two new places inside the soon-to-be-built Moxy Hotel in Washington, D.C.—Atlas will employ more than 1,100 people. And the ambition doesn’t stop there. Smith’s long-range goal for 2020, he says, is to rack up $100 million in sales.

Veteran Cunningham’s chef Cyrus Keefer, who has worked in many restaurants throughout the city, compares Smith to another restaurateur who opened a record number of restaurants up and down the East Coast. “When [James Beard Award-winning] restaurateur Stephen Starr kept opening restaurants in Philadelphia, no one hated Stephen Starr for being Stephen Starr—and that’s who Alex is going to be in Baltimore,” says Keefer. “The city needs the kinds of restaurants he’s opening.”

While it’s axiomatic that everyone loves a winner, it’s also true that success has a way of making you a target, too. And though total strangers like to engage in trash talk about Smith, it’s that public perception that that eggs him on and gives him the smallest chip on his otherwise broad shoulders. “Do I have to work?” he asks. “I have to work, because that’s all I’ve ever known. I don’t want anyone to say to me, ‘Big deal, your grandfather and father had money. You haven’t accomplished anything.’”

Corporate pastry chef Jacqueline Mearman had heard some of the more colorful nicknames for Smith: the Terminator and Darth Vader. Despite that, she interviewed for a job at Atlas. “What I knew was that he was under 40 and had more restaurants than anyone,” she says. “I went in for that interview thinking, I’m not taking the job—and then I met him.”

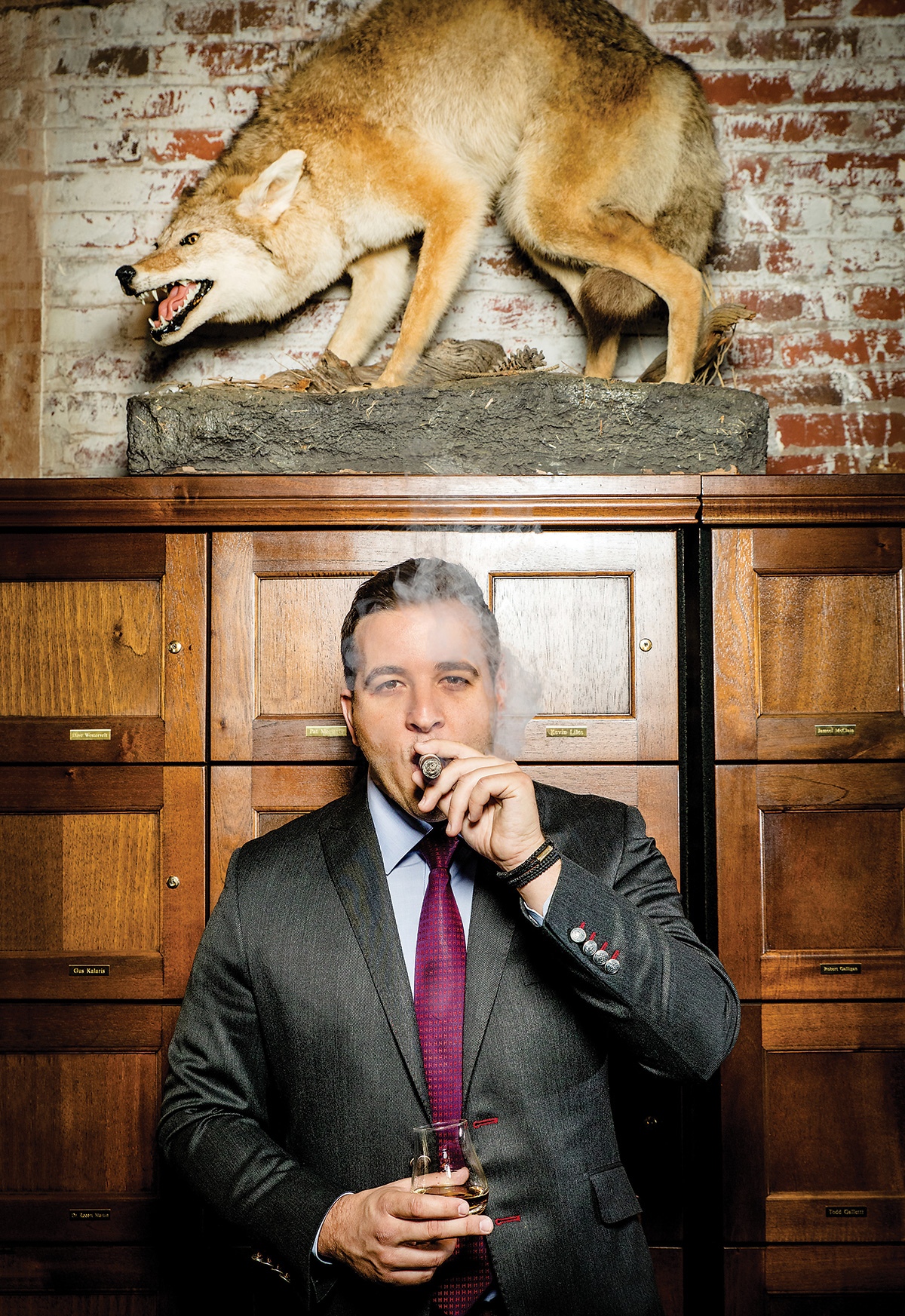

ALEX SMITH is fired up AT his cigar bar

Growing up in Timonium as the oldest of three boys, Smith had no such struggles as the son of doctors Vanessa Paterakis Smith and Frederick G. Smith (who also founded Gerstell Academy, a private school in Carroll County and is a co-owner of Sinclair Broadcast Group, one of the largest independent television broadcasting companies in the country). “I was friendly with everyone in high school and college,” he says. At Boys’ Latin School of Maryland, he was a model student, in possession of both brain and brawn. He was captain of the debate team, president of the honor board, student body president, and an elite athlete who, as a junior, led the school to the Maryland Interscholastic Athletic Association championship in lacrosse and to the ranking of number-two team in the state.

Of course, it didn’t hurt that his bedroom was outfitted with a turf mat, points out his fiancée, Christina Ghani, a national sales and sports manager at Visit Baltimore. “He would roll out of bed and practice,” says Ghani, who was fixed up with Smith by mutual friends a few years ago. “He’d train, train, train in his room for hours—that tells so much about him.” Through sports, Smith learned not only how to play the game, but how to win it. “I’ll never forget when I was in sixth or seventh grade getting into the car after a day when I wasn’t playing well,” he recalls. “And my dad said, ‘Do you even want to be here? Is this something you want to do?’ And I said, ‘Of course it’s something I want to do.’ And he said, ‘Then here’s what your mentality needs to be every time you go out there: If you don’t get the ball, you’re not going to eat tonight. You’re not going to have a place to sleep. You have to go out there and do everything you can to win.’”

It might sound like tough love, but Smith rose to the challenge.

As a college freshman at the University of Delaware, where he majored in business administration and marketing, Smith remained fiercely competitive. “I was very goal-oriented,” he says. “I printed out all the NCAA lacrosse records, and I would break them and then cross them off with a highlighter. It’s the same in business. You have your goals and what you want to do and how you want to expand. And then you cross them off with a highlighter.”

The highlighter approach worked. By the time he graduated in 2007, the Blue Hens’ team captain was regarded as one of the greatest face-off men in all of collegiate lacrosse and held multiple records for it, more than any other player in the history of the sport at that time. While some kids wander aimlessly for a few years after graduating from college, Smith had a clear sense of purpose. While still at Delaware, he made plans to open his first business, a Häagen-Dazs franchise in Harbor East. “The year before I graduated college, my grandfather said, ‘I’m building a movie theater and we need an ice-cream store to go down next to it,’” says Smith. “I said, ‘I don’t know anything about the ice-cream business, but how hard can it be?’”

In 2007, the store opened with a mural of Smith in his lacrosse gear painted on one wall. He worked as his own general manager and put in upwards of 70 hours a week making milkshakes and scooping dulce de leche ice cream. On weekends, he played major-league lacrosse for the Rochester Rattlers.

From the outset, the business was a family affair. He hired Eric and some of his classmates from Boys’ Latin to work behind the counter. By 2010, he opened his second venture, the Harbor East Deli, located just down the street.

Working hard and keeping business brisk came naturally to him, but even then, he endured insults to his face. “Funny story,” he says. “A guy wearing a Legg Mason badge came into the deli, and I’m ringing him up. He orders a slice of pizza and soda, and I say, ‘Small or large?’ And he says, ‘Small.’ And I say, ‘For 50 cents more, you can get a large.’ And he says, ‘Okay, a large’—and then comments, ‘I was just upsold by the pizza boy.’” Smith pauses before getting to the real punch line. “My grandfather owns the building he works in,” he continues. “And he has no idea. I just smiled and didn’t say anything—I’d made my 50 cents.”

Brothers ALEX AND ERIC carry on the legacy OF THEIR GRANDFATHER H&S Billionaire John Paterakis Sr.

Back in his neutral-toned condo—a stone’s throw from the President Street traffic circle that bears his grandfather’s name—Smith seems totally at ease. He’s most comfortable here, amidst the décor that reflects his love of the outdoors, a passion he picked up from spending time with his family on their farms on the Eastern Shore and in Montana. There’s a mountain photograph he shot in Montana, a Peter Lik panoramic Alaska landscape, and a leather chair with an animal skin slung across the back. Although she keeps her own busy schedule, Ghani, who is getting ready for a business trip, sits adoringly by his side. He’s clearly relaxed in her presence. (Months later, they’ll add an Australian Labradoodle, fittingly named Atlas, to their nest.)

Here, at his dark wood dining-room table, looking out over the expanse of Harbor East from the 25th floor, he doesn’t have to be “on.” And it’s often this place where he does his most creative thinking. Back when he was coming up with the concept for Tagliata, for instance, he paged through an Italian dictionary and debated close to 200 names before settling on the lyrical word meaning “chop house.” He also studied 50 different fonts before finding the perfect shaped “T” to grace the menu and logo.

Insomnia, not surprisingly, can be an issue.

“I have a tough time sleeping at night, because I’m thinking of all the different scenarios that could play out,” he says. “If you ask me a question about a business and where we are going, I’m going to give you 20 different ways we can improve. I’m planning for contingencies all the time. Who’s my number two or three person if this or that person leaves? I’m prepared.” And when he can’t give in to sleep because his brain is brimming with ideas, in the wee hours of the morning, he relaxes by watching shows about space or turns on The History Channel. “I watch a lot about military history,” he says. “I love learning about World War II and the Korean and Vietnam Wars, and the ancient stuff, too. What’s fascinating to me is that one moment or another can change the course of history.”

In Smith’s life, the moment that changed everything was in 2000, when his Greek immigrant grandfather decided to invest in the then-desolate neighborhood of Harbor East, and, in doing so, changed the landscape of the city. It’s a torch that he and Eric now happily continue to bear for their beloved grandfather, who also passed along his strong work ethic—even from his hospital bed in the last days of his life. “I would visit him in the hospital, and he’d always tell me to get back to work,” recalls Smith. “He wasn’t an affectionate man, but the night before he died, I was in his hospital room, and I said, ‘Pappous, I’m going back to work,’ and he nodded his head. ‘But before I go, I want you to know that I love you.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘I love you, too.’”

Long said to be the “favorite” grandson, Smith was the recipient of a gift passed down from his Pappous—a ring bearing an antique Greek coin of his namesake, Alexander the Great, a powerful ruler and one of history’s most revered military minds, who established the largest ancient empire the world had ever seen. On weekends, Smith wears the ring on the fourth finger of his right hand and removes it only to show that the gold band is slightly bent, having been molded around his grandfather’s finger. “When I put it on, it fit perfectly,” says Smith. “He wore this every day for 50 years.”

It’s an apt heirloom, as Smith sees himself as the defender of the family. When his grandfather’s second wife, Roula Paterakis, sued his children (including Smith’s mother, Vanessa) for her “rightful share” of the family fortune, Smith was the one who most fiercely guarded his grandfather’s coffers. “I’m really trying to protect the family” is all he’s willing to say on the subject. “I’ve taken on the role of protector.”

The same can be said of his relationship with Eric, the youngest of his two brothers, whom he affectionately refers to as “E.” Although they didn’t attend Delaware at the same time, Eric also played college lacrosse there. After graduation, Eric worked in construction for a time, and then Smith brought him on as a bartender at Ouzo Bay. Now, the two co-own the Atlas Restaurant Group, and Eric has been tasked with overseeing the multimillion-dollar beverage program at all of their properties.

“He’s my best friend,” says Eric of his older brother. He’s more reserved than Smith, though, physically, the resemblance is strong. “I always looked up to him when I was growing up,” he says. Together, the former lacrosse team captains are still leading the team. “We never got a chance to play lacrosse together,” Eric says, “but this is our game now—that’s how I see things. We are athletes. I always knew that we’d be a deadly combination.”

ALEX AND ERIC smith at work—and play—at The Elk Room’s private cigar bar

Ever the competitor, Smith tends to view the world of food service in terms of face-offs and showdowns. On the last Saturday before Labor Day weekend, he has geared up for what feels like an evening battle, which typically begins at 4 or 5 p.m. and ends some 10 or so hours later at The Elk Room for a round of pool and drinks with his top team members—an ad hoc all-boys club including Eric, managing partner David Goodman, Tagliata chef-partner Julian Marucci, and Smith’s director of operations, Brian McCormack.

Like a modern-day warrior, dressed in a burgundy jacket with a silver “A” pin (for Atlas), a custom Tom James gray-striped shirt, his favorite J. Brand jeans, and blue leather Gucci loafers, Smith sips a shot of double espresso from Ouzo’s kitchen and gets pumped for the night ahead. As he rounds his Harbor East properties, Ouzo is his first stop of the night. He checks the fish case, pointing out the mammoth langoustines from Norway, discards a wrinkled menu, and checks the evening’s reservations, noting that there are two sets of regulars he’d like to greet when they arrive. “On the first walkthrough, I’m mostly checking tables and chairs and that displays are set up,” he says. “I say ‘Hi’ to the chef, and the second time I swing around, I’m greeting guests.’”

Still at Ouzo, he points out a newly installed DJ booth, part of the “program” in which Atlas spends approximately $300,000 a year for music, such as the live jazz at The Elk Room or the piano player on the 1926 Steinway at Tagliata.

“I don’t want anyone to say to me, ‘Big deal, your grandfather and father had money. You haven’t accomplished anything.’”

More than anything, he loves talking about the restaurant business—about his restaurants, other Baltimore restaurants, and restaurants he’s eaten in from Miami to Tokyo. “You want to know why restaurants are closing?” he asks. “They are closing because the restaurant business is evolving—and the restaurants are not evolving with it. So when you see places closing, or these places that have been in business for 25 years providing decent food in an okay atmosphere, that’s not enough for businesses to be successful anymore. Millennials go home and get on Grubhub or Uber Eats if they want a turkey club. To get the millennial off the couch, it’s not just about the food anymore. It’s about the entertainment, it’s about the experience. Restaurants in Baltimore are dying because they are doing the same thing they did 20 years ago.”

Prior to opening a restaurant, Smith has been known to do painstaking research. For Tagliata, he ate his way through the great chophouses of America, from New York to Houston. For Azumi, he traveled to some of the country’s top-tier fish palaces—Nobu, Morimoto, Zuma—and recently took a team of staffers to Japan for new elements such as a robata grill and soon-to-open teppanyaki table. For Ouzo Bay, he drew on what he knew from frequent family trips to the Greek homeland and dined at chichi Hellenic hotspots like Milos in New York.

And he approaches it all as if he’s still on the turf field of his childhood. His father’s words—Go out there and do everything you can to win—likely looping over and over in his head. “No one is going to outwork me,” says Smith, as he continues his swing across Harbor East. “I check in with every dishwasher. I talk to the runners, and the bussers, and the hostesses, and the managers, and the chefs. I make the rounds and greet the guests and am in the kitchens every night. It’s a grind, and you have to have the will to do it.”

After Ouzo, it’s on to Loch Bar, a 2,700-square-foot, upscale seafood house he says is one of the highest-grossing restaurants on the East Coast per square foot. “Even higher than Le Diplomate,” he says, referring to Stephen Starr’s popular French bistro in D.C. Then he’s off to Harbor East Deli, where he makes sure that former mayor Sheila Dixon’s catering delivery to the Marriott Waterfront for her daughter’s wedding party went smoothly; to Azumi, where Smith speaks with chef Andy Gaynor about the 200-pound tuna they hauled in last week from Japan for a glossy Atlas promotional video; to Bygone to talk about a new chef’s coat and aprons with executive chef Matthew Oetting; and to The Elk Room, to walk the floor and remind a staffer to have a new employee sign a nondisclosure form for the private cigar club.

MAKING THE DAILY ROUNDS IN HARBOR EAST.

The last stop on the rounds is Tagliata, where he throws on the spotlight over the piano (“They always forget to do that,” he says.), before hitting the street to hug some of the valets standing outside Italian Disco and rounding back to Ouzo Bay again.

“With each concept, we are giving something back to the city,” says Smith as he walks briskly down Fleet Street. “We are trying to bring unique experiences to town. In our own small way, we are making a difference, and that’s why we keep going. Part of the drug-like effect for me is seeing people walk onto the properties and say, ‘Wow, look at this. Can you believe we have this in Baltimore?’”

As the night wears on, Smith is increasingly energized, engaging in a new version of one of his favorite pastimes—crunching numbers (once, for fun, he figured out that his grandfather had sold enough bread each year to make it to the moon and back) and checking the restaurant’s “stats,” using his dining analytic apps to look at such things as the number of guests dining at each restaurant, real-time sales figures, photos of the dining rooms, VIPS, even a customer’s favorite drinks. “Look at this,” he says, gesturing to his phone. “We’ve served 300 at Azumi, 250 at Ouzo, 300 at Bygone, 350 at Tag, then there’s Disco, Elk Room, Loch Bar, that’s about 1,800 to 1,900 sit-downs.” He cites some impressive off-the-record sales figures and sums up, “Just say that we are selling a lot of food.” When he’s not in the “back of house” with his staff, Smith is in the front with customers, shaking 200 to 300 hands each night by his own estimate. Inevitably, he says, pointing to his shoulder, “by the end of the night, my jacket will have all of this lipstick and make-up on it from the hugs.”

On any given evening, those hugs and handshakes might come from “regulars” such as Maryland Public Television stalwart Rhea Feikin, Ravens owner Steve Bisciotti, Maryland Shock Trauma chief Thomas Scalea, or Sun shutterbug Sloane Brown. On this night, that includes schmoozing with the executive vice president and CFO of Exelon, Joseph Nigro, and his wife, Melissa.

While Smith see himself as the great protector of the family, he also sees himself as a defender of the city that he loves—one that tends to get a bad rap. “I care about building something,” he says. “These restaurants will not be here in many years to come, so it’s not about the bricks and mortar, but an idea. They are important to the culture of the city. It’s important that Baltimore be thought of not just as a place with a bunch of crab shacks. I want to make an investment here and see the city grow.” Late at night, after the rounds have been made, after most of the patrons have headed home, inside The Elk Room, Smith leans on a leather wingback chair and is feeling contemplative as he talks about his love of the cosmos and the constellations. In his tired state, his mind starts to wander. “I love to think about the unknown,” he says. “It’s why I love space. When astronauts come back from space, they describe this sense of euphoria, this feeling of awe that they get at looking down and seeing the 7.5 billion or so people who live on earth.”

On a more micro level, it’s the feeling he gets when he sees people eating in his restaurants. But while he’s a bigwig in Baltimore, he holds no delusions about his place on the planet. “We are dust down here,” he says. “I’d love to go to space and get that feeling of euphoria.”

It could happen one day, since for Smith—like his grandfather—not even the sky seems to be the limit.