Business & Development

Back as Under Armour CEO, Kevin Plank is Ready to Take on the World’s Top Athletic Brands

Under Armour is once again the underdog—but maybe that’s what it needs to thrive.

Under Armour’s sleek new global headquarters gleams on the edge of the Baltimore Peninsula, shading the crowd gathering along the building’s west facade from the warmth of the rising sun.

They have ventured out on this chilly morning in December to celebrate the grand opening of Under Armour’s Flagship Brand House, a reimagined retail experience that covers 24,000 square feet. It’s billed as the fusion of athletic innovation, passion, and storytelling—the things Under Armour is leaning into to reconstitute its brand identity.

The temperature has barely inched past 20 degrees.

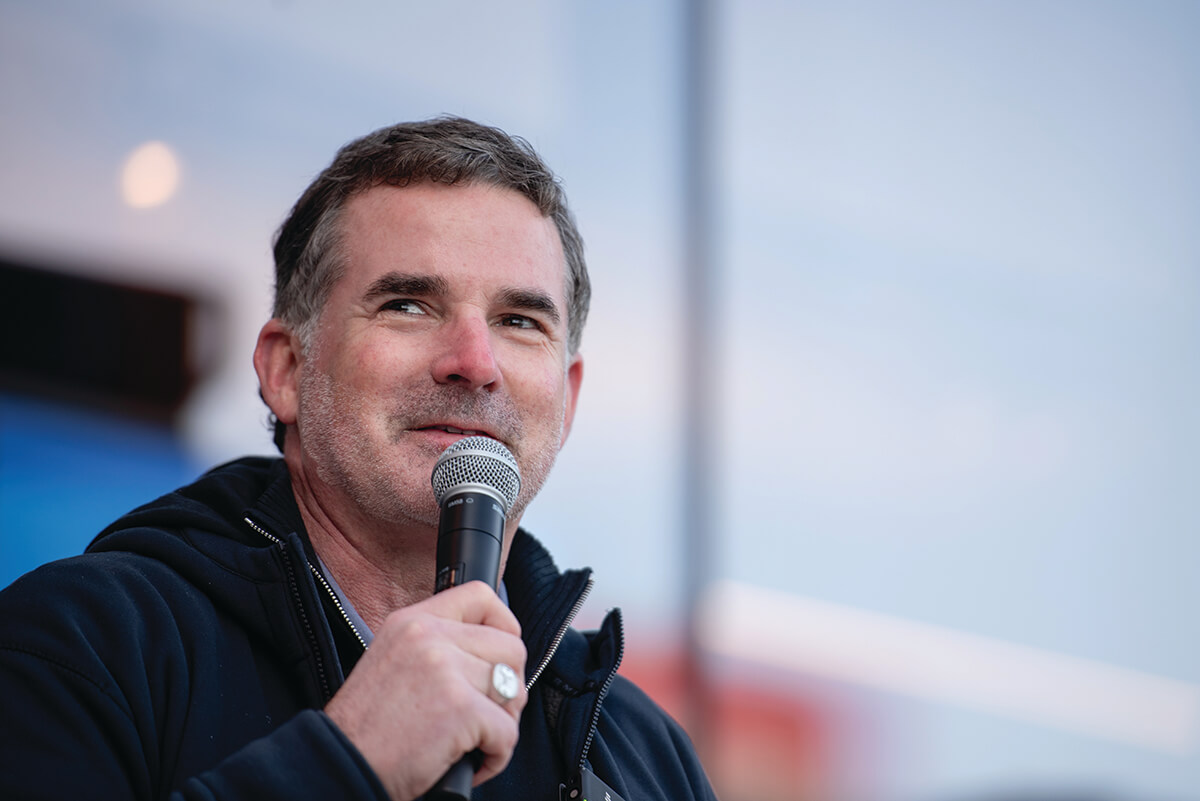

“I thought it would be colder, so I wouldn’t need to talk long, but I’m wearing Under Armour, so I might take a few minutes,” says a mic-wielding Kevin Plank, who’s layered in a logoed navy blue jacket, black zip-up sweater, and pale blue collared shirt. His presumably off-brand black jeans touch the tops of company-issued purple and gray sneakers.

The throwaway line scores chuckles and cheers from the gaggle of onlookers who blow into their hands and grip paper cups filled with complimentary hot chocolate.

Plank stands next to a podium emblazoned with the crisscrossed “U” and “A” that form his company’s iconic logo and turns to acknowledge the local dignitaries who have shown up to support Baltimore’s hometown brand. Mayor Brandon Scott and Councilwoman Phylicia Porter are there. So is University of Maryland’s head football coach, Mike Locksley. WNBA superstar Kelsey Plum, who is on Under Armour’s roster of athlete ambassadors, adds an air of national celebrity to the festivities.

“Today, standing here and surrounded by all of you—I’m just damn proud,” says Plank. “I’m proud of this company, proud of our journey, proud of our resilience. We’re the underdog brand that’s defined by its lunch-pail-carrying, get-the-job done attitude that matches Baltimore’s grit and determination.”

Plank counts down to the official opening of the Brand House and pushes an oversized red button that sets off a burst of pyrotechnics and welcomes the crowd in from the cold as the Towson University marching band plays stadium fight songs.

It’s an intoxicating scene and makes you believe in Under Armour’s unmet potential.

For Plank, it’s an opportunity to turn the page on years of controversies, stagnant sales, and lack of a clear brand identity that caused him to step down as the company’s CEO before retaking the top spot a year ago. He’s back to regain the buzz Under Armour created when it burst onto the scene and reshaped the athletic apparel industry in the 1990s. He understands the challenges ahead and hears the skeptics. He also remembers the first time he beat the odds to launch a revolutionary company from scratch.

“I get reflective on a day like this,” says Plank. “When you’re an entrepreneur and you’re just getting going, you’re constantly looking for validation. Have I gotten better? Are we growing? You’re just trying to find a way.”

Under Armour’s origin story is the stuff of start-up legend. Plank grew tired of wearing sweat-soaked cotton T-shirts under his uniform as special team captain of the University of Maryland football team.

After graduating, he prototyped what would become Under Armour’s signature HeatGear T-shirt, a performance base layer that wicks away moisture to keep athletes dry during intense workouts. It was a game-changing design. HeatGear technology has since redefined the market and informed the design of sports apparel across all brands.

Plank traveled up and down the East Coast, selling the shirt out of the trunk of his car. By the end of 1996, he had earned $17,000 in literal direct-to-consumer sales and launched Under Armour while living and working in his grandmother’s Georgetown rowhome.

Under Armour’s revenue exploded to nearly $300 million by 2005, the year it went public. Annual sales cracked $1 billion in 2010 and continued to climb past $5 billion as the company strung together years of revenue growth of at least 20 percent. However, the company reported a net loss in 2017 as growth slowed to the single digits and stock prices tumbled.

Controversies also began to swirl. The Securities and Exchange Commission charged Under Armour with misleading investors about its revenue growth in the second half of 2015, forcing the company to pay $9 million to settle the matter. Under Armour also paid $434 million to settle a class action lawsuit filed in February 2017 that accused the company of defrauding shareholders about its revenue growth to meet Wall Street forecasts.

Under Armour was no longer an industry darling. Plank stepped down as CEO at the end of 2019 but remained onboard as executive chairman and brand chief. Industry analysts generally applauded his decision, believing the company would benefit from a fresh voice and new direction. Plank lasted on the sideline for close to five years before returning as president and CEO in April 2024.

The sudden and surprising move was met with skepticism. Yes, Plank possesses an innate understanding of Under Armour that only a founder can have and grew the company into a multi-billion-dollar business, but some industry analysts wondered if he could fix the problems that he helped create.

“Under Armour seemed to lose sight of its unique selling proposition and, at times, didn’t quite understand its consumer,” says Danni Hewson, head of financial analysis at AJ Bell, a personal investment firm. “It produced too much of what people didn’t want, particularly during a time when there was already excess inventory in the market.”

HE UNDERSTANDS THE CHALLENGES AHEAD AND HEARS THE SKEPTICS.

With that in mind, Plank immediately announced plans to streamline Under Armour’s product offerings by 25 percent and institute faster go-to-market capabilities. The idea was to spend less time and resources on producing repetitive sportswear so the company could refocus on introducing innovative products that reimagined how active apparel feels and functions.

Plank points to Under Armour’s Stealth-Form Uncrushable Hat, which was introduced a year ago and is made of proprietary cooling material, as the type of forward-thinking design consumers can expect from the company and promises similar types of products are in the pipeline for release later this year.

“Under Armour has made a lot of good products and some better products, but nowhere near enough best-level products,” he says.

During an earnings call last November, the halfway point of the company’s fiscal year 2025, Plank reported $50 million more in adjusted operating income than what the company had forecast. He said half of that found money would be spent on marketing and brand building efforts to deepen the company’s connection with consumers. Plank’s turnaround efforts were beginning to gain traction, but industry analysts warned about a long road ahead in a fragmented athletic apparel industry that makes it difficult for Under Armour to stand out.

“The level of innovation in the market has increased significantly,” says Hewson. “Consumers are interested in purchasing the latest hot product instead of remaining loyal to a brand.”

To make matters worse, Under Armour has lost shelf space at big box retailers that help drive sales. David Swartz, senior equity analyst at the investment research firm Morningstar, says the company used to generate about 40 percent of its revenue through Dick’s Sporting Goods and Sports Authority. When Sports Authority went bankrupt in 2016, Dick’s was also struggling financially. Under Armour responded by shifting most of its inventory to Kohl’s, a decision that proved costly.

Although Dick’s didn’t cut ties with Under Armour, it began to reserve prime shelf space for Nike and Adidas and rising newcomers like On and HOKA. Even Puma and New Balance, which have seen a brand resurgence in recent years, are prominently displayed. Under Armour is no longer at the top of Dick’s preferred brands list, preventing it from riding the wave of explosive sales growth the sporting goods chain has experienced in recent years.

Under Armour’s brand visibility took another hit when Kohl’s was forced to close several stores in 2024 due to slumping revenues. Swartz believes Under Armour can improve its retail presence by rebuilding its relationship with Dick’s and prioritizing other stores, particularly Foot Locker, which is diversifying its brand offerings and presents a growth opportunity.

Under Armour’s revenues currently rely heavily on selling discounted products at outlet stores. Plank wants to move away from that business model by creating a premium brand that consumers will pay full price to wear.

“For that to happen, the products need to be high quality, innovative, and deliver on their performance promises,” says Hewson. “Under Armour’s focus on innovating practical sportswear is key. If the company manages to position itself as an aspirational but affordable brand, it can persuade consumers to buy at full price. It’s a delicate balancing act. Products need to be desirable while remaining accessible.”

Under Armour has had a 12-year partnership with NBA superstar Steph Curry, one of the world’s most marketable athletes. The company launched the Curry Brand in 2020 and opened the first brand-dedicated store in China last September. Swartz believes the brand is underdeveloped, despite the enormous popularity of the Curry line of basketball sneakers.

“There hasn’t been a widespread consumer recognition of the Curry Brand as a distinct entity like Nike’s Jordan Brand,” he says.

[UA] WANTS TO MOVE PAST BEING A BRAND THAT SELLS ON PRICE TO ONE THAT SELLS ON STORY.

Rather than venturing into the casual athletic or athleisure market, which companies like Lululemon have successfully mined for significant revenue, Under Armour has remained focused on competing with Nike and Adidas for the attention of 16- to 22-year-old varsity athletes, a core demographic the company targets to maximize its reputation as an authentic team sports brand, a differentiator that Plank believes is key to driving the company’s future success.

Still, Swartz remains relatively optimistic about Under Armour’s prospects in a dynamic global market that offers opportunities for multiple winners.

“The key question is whether Plank can capitalize on those opportunities,” he says. “Shifting from being a niche brand to a serious player in global sports requires investing heavily in marketing and product innovation—and quickly. The competition isn’t standing still.”

Eric Liedtke, Under Armour’s executive vice president of brand strategy, says the company has the reputation of a performance-centric training brand for individuals, and men in particular, who are 34 and older—loyalists who grew up wearing the logo.

He acknowledges that Under Armour has been viewed as a bit too tough and intense in its efforts to connect with younger athletes in the past. Think about the company’s iconic ad campaigns and accompanying visuals. Protect This House. The Only Way Is Through. Scowling, sweat-stained athletes in shadowy portraits.

That will all change, says Liedtke, who vows to express the brand in fresh ways that appeal equally to young male and female team athletes, a demographic the company is “maniacally focused” on reaching.

“We’re going to channel the full energy of the brand into messaging that comes through as determined, passionate, fun, and yes, still a little tough and intense,” says Liedtke. “This positioning will be expressed in the most impactful marketing campaign in the company’s history that includes two chapters—reasons to love us and reasons to buy us.”

Under Armour wants to move past being a brand that sells on price to one that sells on a story, according to Kara Trent, Under Armour’s president of the Americas.

“We know the formula,” she says. “We have a portfolio of teams and athletes. We have product franchises and innovations, and we have the platform established to drive meaningful consumer experiences. But now we must execute integrated stories that drive connection to younger athletes—and do it at a level of impact and repetition like never before.”

Plank is back as Under Armour’s CEO because he wanted to be, and the company’s stock structure gave him the majority voting power he needed to retake the top spot. The power play was controversial among industry analysts, but it’s likely that no other executive would want the company to thrive more than Plank does.

“The one thing that he brings to the role is his unique understanding of what Under Armour is,” says Hewson. “A lot of founding CEOs can’t let go because they haven’t figured out a way to impart that knowledge to somebody else in a way that will make their company successful.”

Is Plank’s passion for the brand born from blood, sweat, and tears enough to drive top-line growth? Time will tell. Change won’t happen in the short term.

During the Brand House’s grand opening celebration, pictures of Plank sitting behind cluttered desks in Under Armour’s former office spaces appear behind him on a large digital screen. He tells the crowd that he came up with the “buy a new desk” mantra to gauge the company’s growth during the white-knuckle start-up days when bills were stacked higher than sales receipts. Business was good, his thinking went, if he could afford larger and more ornate work surfaces.

In 1996, the year Under Armour grossed $17,000, Plank bought a $350 IKEA desk. It wasn’t much, but it represented progress.

As revenues grew, Plank needed to expand Under Armour’s operations. He moved out of the Georgetown rowhome in 1998 and into a small space on South Sharp Street in Baltimore. Buy a new desk. Further growth necessitated moves to moderately sized offices on Bush Street and eventually to a large campus on Tide Point. Buy a new desk.

Plank is now standing outside his company’s latest home, a state-of-the-art facility that glows bright red at night, joining the Phillips and Domino Sugars signs as illuminated landmarks that define Baltimore’s skyline and identity.

Plank recounts Under Armour’s journey to remind the crowd, and perhaps even himself, that the company achieved its greatest success when the odds were stacked against it. Under Armour is once again the underdog. Maybe that’s what it needs to thrive.

“I’m approaching the brand like it’s a $5 billion start-up,” says Plank. “Watch as we show the world how great we can be and make this city proud. We’re just getting started.”

This year we celebrate our 50th Best of Baltimore issue—our biggest and boldest yet. Subscribe before 6/20 to guarantee your copy commemorating this milestone anniversary.