News & Community

The Last Autoworker in Baltimore

After 85 years of local history, General Motors has shuttered for good. Like Bethlehem Steel, it has been replaced by an Amazon fulfillment center.

Guy White’s alarm goes off at 4:40 a.m. The same time it has for the past decade for the UAW Local 239 shop steward. It’s early, but it beats the years working nights and crazy swing shifts. He tries not to disturb his wife—the kids are grown and gone—and starts a pot of coffee. He grabs a couple of hard-boiled eggs, packs a sandwich for his lunch box, and attempts to keep his thoughts on his daily routine. Most of the coffee, as usual, ends up in his thermos for the 20-minute commute to White Marsh and the General Motors plant there, which has been sitting idle, as quiet as his kitchen at 4 in the morning, since mid-May. It is now the third Friday in September, and the United Automobile Workers’ existing contract with GM is set to expire over the weekend. He’s scheduled to fly to Detroit the next the day to vote on GM’s offer and whether the UAW should strike over wages for new hires and recent plant closings.

UAW Shop Steward GUY WHITE IN FRONT OF THE UNited Autoworkers UNION Hall IN GREEKTOWN Just

Prior to THE SHUTDOWN of

the GM PLANT

IN white Marsh.

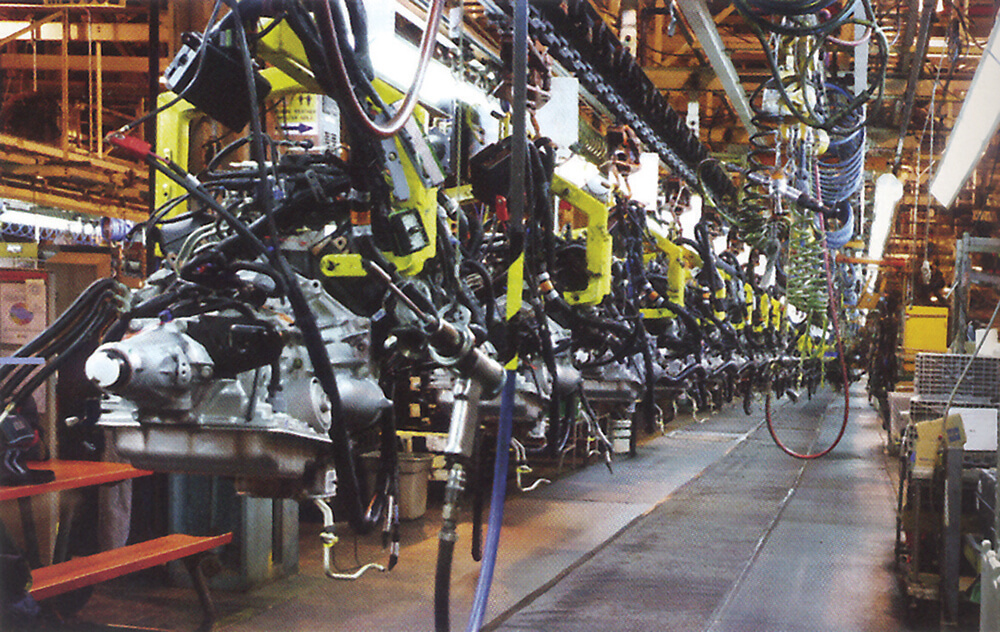

For White, however, and the 250 White Marsh union autoworkers, the die has been cast. Late last year, GM informed them that the plant’s beloved-by-gearheads, six-speed, heavy-duty Allison transmission—the kind that powers the Silverado and Sierra pickups—was being replaced by a newly designed 10-speed transmission. That new transmission, management added, would be made in Ohio.

For the past few months, White had kept going to his office to facilitate relocations and retirements for his fellow UAW members. In fact, White was so sure that Friday morning in September would be his last that he had cleaned out his desk and booked a Delaware shore vacation. He put in 19 years at White Marsh and, before that, 15 at the old GM facility on Broening Highway. When he clocks out at 2 p.m., it punctuates the end of GM’s epic 85-year relationship with this city.

At its peak here, the Big Three automaker produced American classics such as the Pontiac Grand Prix and GTO, the Chevelle and Monte Carlo, the Oldsmobile Cutlass and Buick sedans—not to mention Chevy pickups, station wagons, and later, three million Astro and Safari minivans. Even during the stagflation of the 1970s, the Broening plant hummed along, employing 7,000 autoworkers in Southeast Baltimore. In those days, Western Electric and Lever Brothers were still down the street; Bethlehem Steel was a stone’s throw away.

“General Motors announced after everyone returned from the Thanksgiving holiday the plant would become ‘unallocated,’ meaning we wouldn’t have a product,” White explains, standing outside the UAW union hall in Greektown on a recent morning. He’s still trying to understand management’s decision to close the factory, which had also produced Chevy Spark electric motors, and to grasp the end of the automobile manufacturer’s near-century history in his hometown.

“I’m 62. My wife wants me to retire, but I was hoping to work a few more years,” White says. “We were still busy, working seven days a week to fill orders.”

Two weeks later, walking a picket line outside the empty, 600,000-square-foot facility in support of the national strike that was eventually called by UAW (and finally resolved last week) White continued to push the case for his plant. “We have experience in electric motors. We have experience in transmissions,” he tells a reporter from The Sun. “This is a good-sized building. I don’t care what we build. Scooters? Bicycles? Just give us something to build.” Instead, the union hall itself is for sale.

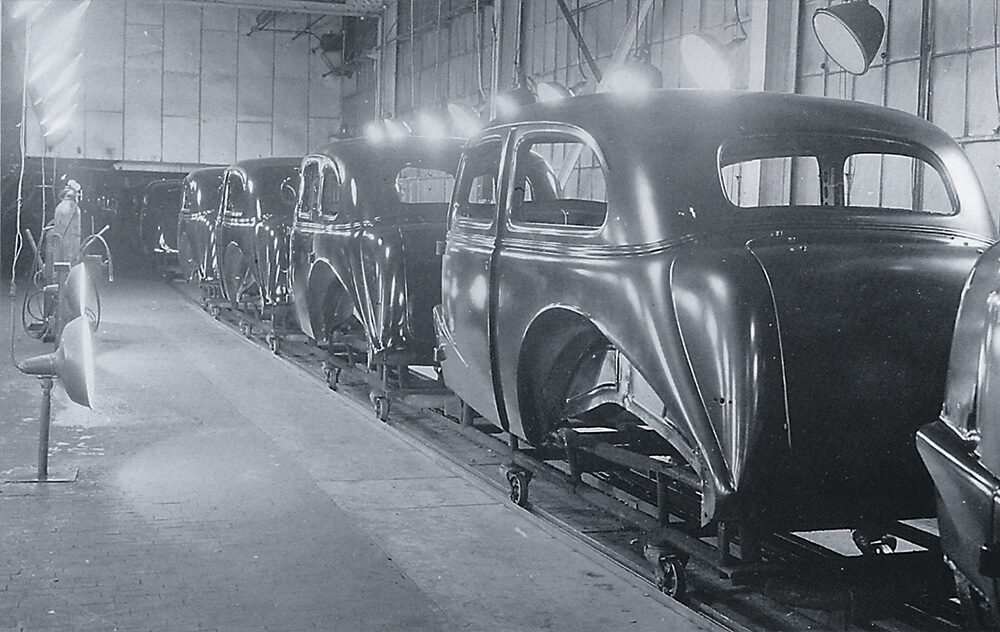

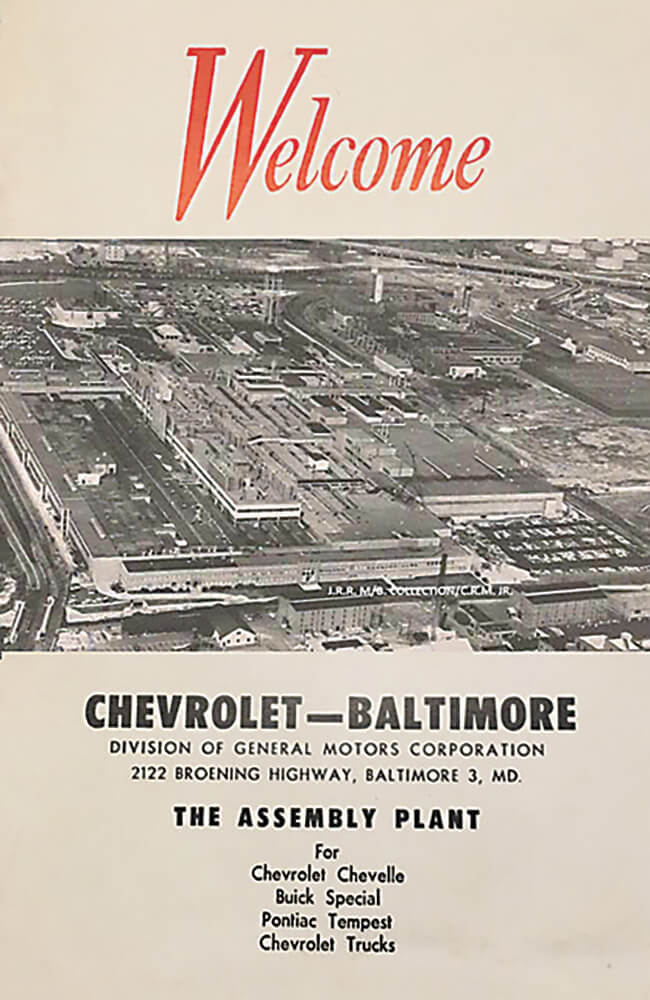

The story began in the fall of 1934: With the automobile industry exploding, representatives from the Chevrolet Motor Company, a division of GM, came to town to put shovels in the dirt alongside then-Mayor Howard Jackson for the groundbreaking of a massive assembly and body plant at Broening Highway. A dozen years earlier, there had been one automobile on the road for every 11.5 Americans. By the time the plant opened, there was already one car for every four people. To keep pace, Chevrolet said the factory would be operational in record time, produce 80,000 vehicles a year, and, with the nation in the throes of the Great Depression, deliver 1,500-2,000 jobs. It was a godsend. City officials promised only Baltimoreans would be hired, and Chevy executives were feted with a downtown parade.

Covering the equivalent of 40 football fields, the original GM plant consisted of five buildings, rail lines, driveways, walkways, test roads, and a parking lot for employees’ cars. (At a recent UAW retirees meeting, 100 percent of the vehicles in the packed Oldham Street lot were American-made, 95 percent GM brands.) The first trucks and cars rolled off in March 1935. That May, the United Automobile Workers was founded in Detroit.

In Baltimore, the auto industry, GM, and the UAW would come of age together.

Even during THE stagflation OF THE 1970S, THE Broening PLANT hummed along, employing 7,000 autoworkers in Southeast Baltimore.

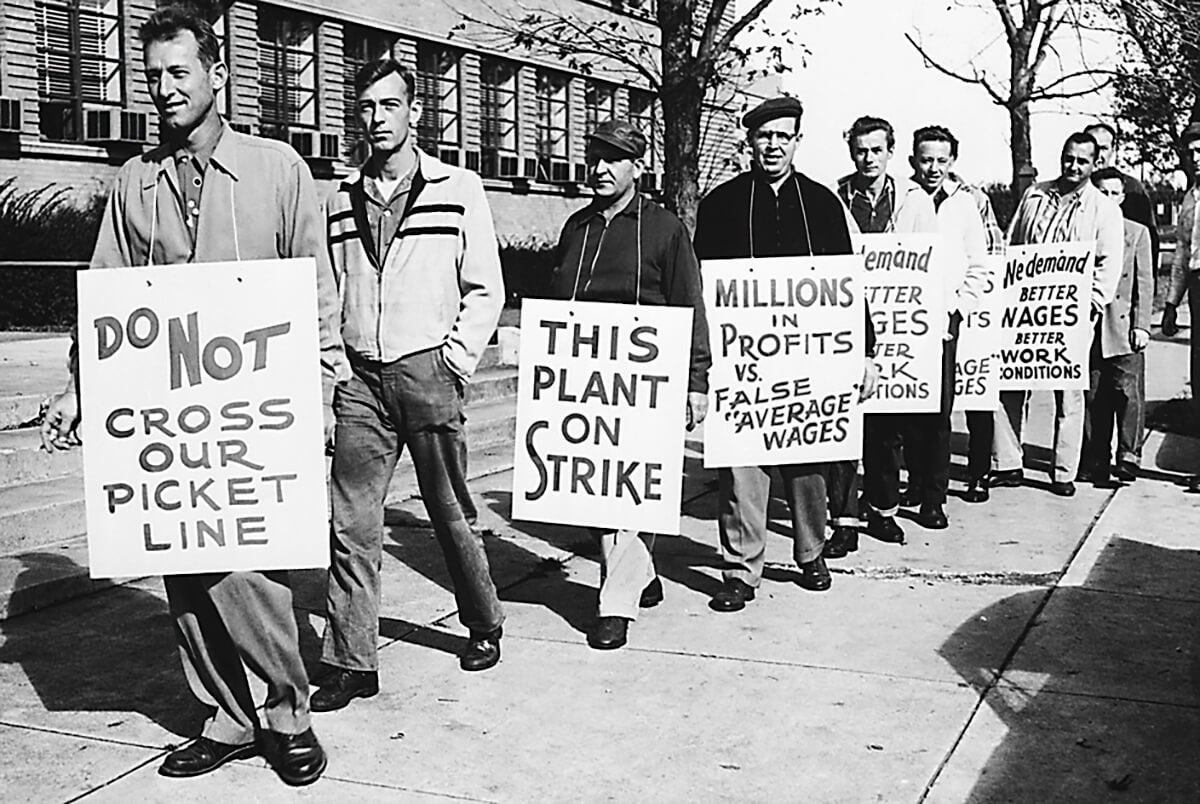

“It was a time of a huge organizing movement, in large part because New Deal policies and court decisions made it possible,” Baltimore labor historian Bill Barry explains. “There were marches and tough sit-down strikes in the ’30s, including a two-month strike in Flint [settled when Michigan Governor Frank Murphy negotiated GM’s recognition of the UAW in 1937], and the creation of the National Labor Relations Board.” Ford, which had set up a security and espionage unit within the company and was not reluctant to use violence against union organizers and sympathizers, didn’t recognize the UAW until 1941. “By the 1950s, an era many people say they want to return to, more than a third of the U.S. workforce was represented by a union,” Barry adds. “Today, it’s 11 percent.” Those union jobs at GM, as well as Bethlehem Steel, once the world’s largest steel plant, became the bedrock of Southeast and East Baltimore neighborhoods in the city, and Dundalk, Turner Station, Rosedale, Parkville, Essex, and Middle River in the county.

“Half of Dundalk worked at Beth Steel, the other half at GM,” says Fred Swanner, a past UAW Local 239 president, who graduated from Dundalk High School in 1968 and started at Broening Highway a few days later. “You didn’t turn down a job that good. [Economists] say each job at a GM plant generates or affects five to seven other jobs and someone in every household worked at one of those two places, or the Port, or a job that supported those industries.” The Broening site, which over time tripled in size to 180 acres, sat inside the city line, with Dundalk on the other side. By 1960, with a population topping 85,000, Dundalk was the second-largest city in the state. But like Baltimore, it shed 30 percent of its population over the next few decades—the result of the city’s and nation’s deindustrialization—and long ago became a symbol of changing economic conditions. Jimmy’s Famous Seafood remains on Holabird Avenue, but nearly every other GM post-shift bar and restaurant, the Chevrolet Inn and Poncabird Pub, to name two, have disappeared.

Looking for a real-time bellwether? A one million-square-foot Amazon fulfillment center sprang up on the exact site of the demolished Broening Highway plant in 2015. It was no small coincidence that at Sparrows Point, atop the same grounds where Baltimore steelworkers smelted the iron ore that built the Golden Gate Bridge and the Empire State Building—and the muscle cars down the road at GM—a second, 855,000-square-foot Amazon fulfillment center popped up last year. Needless to say, the thousands of packaging jobs at Amazon—the highest-valued company in the world, owned by the wealthiest man in the world—pay half the wages of a union steel or automobile job. And they don’t include the health, pension, vacation, sick and family leave benefits, nor the job protections that typically come with a collective bargaining agreement. From August 2017 to September 2018, for example, 300 workers were fired from the Amazon fulfillment center at Broening Highway, according to documents from a recent wrongful termination suit. “It’s a sign of the times,” Barry laments. “But it’s up to them to organize,” he says of Amazon workers.

Meanwhile, GM’s decision to close its modernized White Marsh plant remains frustrating, to say the least, for UAW members and the elected officials who fought for $115 million in local, state, and federal grants to build its electric motors operation in 2012. That money came on top of a federal $50 billion bailout loan (cost to taxpayers: $11.2 billion) during GM’s 2009 bankruptcy.

“It’s a killer,” says Congressman C.A. “Dutch” Ruppersberger of GM’s decision to close the White Marsh facility. “And it makes me mad.” Ruppersberger pushed for the plant when he served as Baltimore County Executive and its subsequent revamping while on Capitol Hill. By GM’s own metrics, it’s one of its most efficient facilities in North America, he notes. “The American people invested in General Motors, and GM shows no loyalty in return,” Ruppersberger says, his voice rising. “There’s no loyalty to the community and to the taxpayers that have made their shareholders a lot of money. Instead, they’re moving plants to Mexico. It’s corporate greed,” continues Ruppersberger, who fired off a letter to GM CEO Mary Barra, attempting to claw back the taxpayer grants without success.

Worth highlighting: GM earned $35 billion in North American profits over the past three years. Barra, whose father was a UAW tool-and-die maker for 39 years, makes 295 times the average employee and took home nearly $22 million last year.

Courtesy of GM ARCHIVES

pamphlet describing the Baltimore Assembly plan.

At 18, Guy White, the future UAW shop steward, enrolled at then-Towson State University after graduating from Perry Hall High School in 1975. But he quickly realized he didn’t want to sit in a classroom for another four years. He liked working with his hands and figuring out how things functioned and took a job in a motorcycle shop. Riding was a hobby. He realized soon enough, however, the pay wasn’t going to cut it. He tried driving a truck. Again, he didn’t see a future in it for himself. “I couldn’t take staring at the road all day,” he says. Eventually, an acquaintance, and good math scores, landed him a steamfitter apprenticeship. It was a path to earning a genuine living, and he asked his girlfriend, now-wife Clare, to marry him. Following assignments at the former Hawkins Point Glidden Paint factory and toxic Allied Chemical plant in Harbor East (“You could see the vapors rising toward the skylight windows.”), he was relieved when he got switched to the Broening plant. He quit the steamfitters local to join the UAW just after GM awarded the plant a major minivan contract. For the next two decades, sturdy, no-frills Astros and Safaris were the plant’s lifeline. When sales slipped in the early 2000s, GM pulled the plug on the facility without ever bothering to upgrade the minivans’ design or retool for another product.

White, fortunately, had already moved to the White Marsh transmission plant. As the Broening facility wound down, 2,100 UAW members were forced to other plants—mostly in Michigan and Texas. “I was lucky.”

He and Clare had bought a brick, Cape Cod-style home in Parkville. Four bedrooms, two upstairs and two downstairs. They raised three kids there and sent them to college. They went to Ocean City. “Do you get rich working in a union? No. Was it easy? No,” says White, who, at 6-foot-1, remains solidly built. “Working in an auto plant isn’t for everyone. But being part of a union meant my wife could be with the kids. It meant we worked with a sense of purpose and dignity, which was important to me, personally. Even before I was hired there, my father drove Chevrolets because that’s where people who lived in our neighborhood worked. You know, there still isn’t anything out of Germany or Japan that’s better than the Allison transmissions we made.

“I got 30 years in and can retire with a pension,” he says. “I joined the UAW in 1985, the beginning of the end for manufacturing and union jobs in this country. I tell people I feel like a surfer who caught the last wave.”

Striking Baltimore UAW Members in 1958. Courtesy of GM ARCHIVES

But others are still scrambling. Lou Phipps, a forklift operator at White Marsh, needs two more years to retire. UAW benefits rep Cindy Alfred-Smith is in the same boat, only with more cargo. She’s worked for GM for 25 years, has two kids in school, and now is faced with the likelihood of having to pick everyone up and move to a different part of the country. Several temporary workers, who had jumped from Amazon to the White Marsh plant in hopes of earning fulltime UAW jobs, are out in the cold with the factory’s closing. John Sofia, who has 25 years in, plans to move to Missouri, which would be his sixth GM plant, in an attempt to earn his 30-year pension. He recently moved his mother, suffering from dementia, into a nursing home and likely will have to leave her here and trek back and forth when he can. “Everybody has worked at multiple plants,” says Phipps. “We call ourselves ‘GM gypsies’ because you make so many moves to get your time in, as one plant after another closes. It’ll be five plants for me—Broening Highway to Wilmington, Delaware to Lordstown to White Marsh now to Missouri. It takes a toll on families. Many times, one spouse has a job they can’t leave, or they don’t want to sell the house, take the kids out of school. People work and drive home from Massachusetts or Ohio on the weekend. It causes a lot of divorces.” Phipps’ son Tony also worked at White Marsh. He’s already transferred to a Texas plant, but his wife, a nurse, and children are remaining here for the time being.

inside the amazon center where the gm plant used to stand.

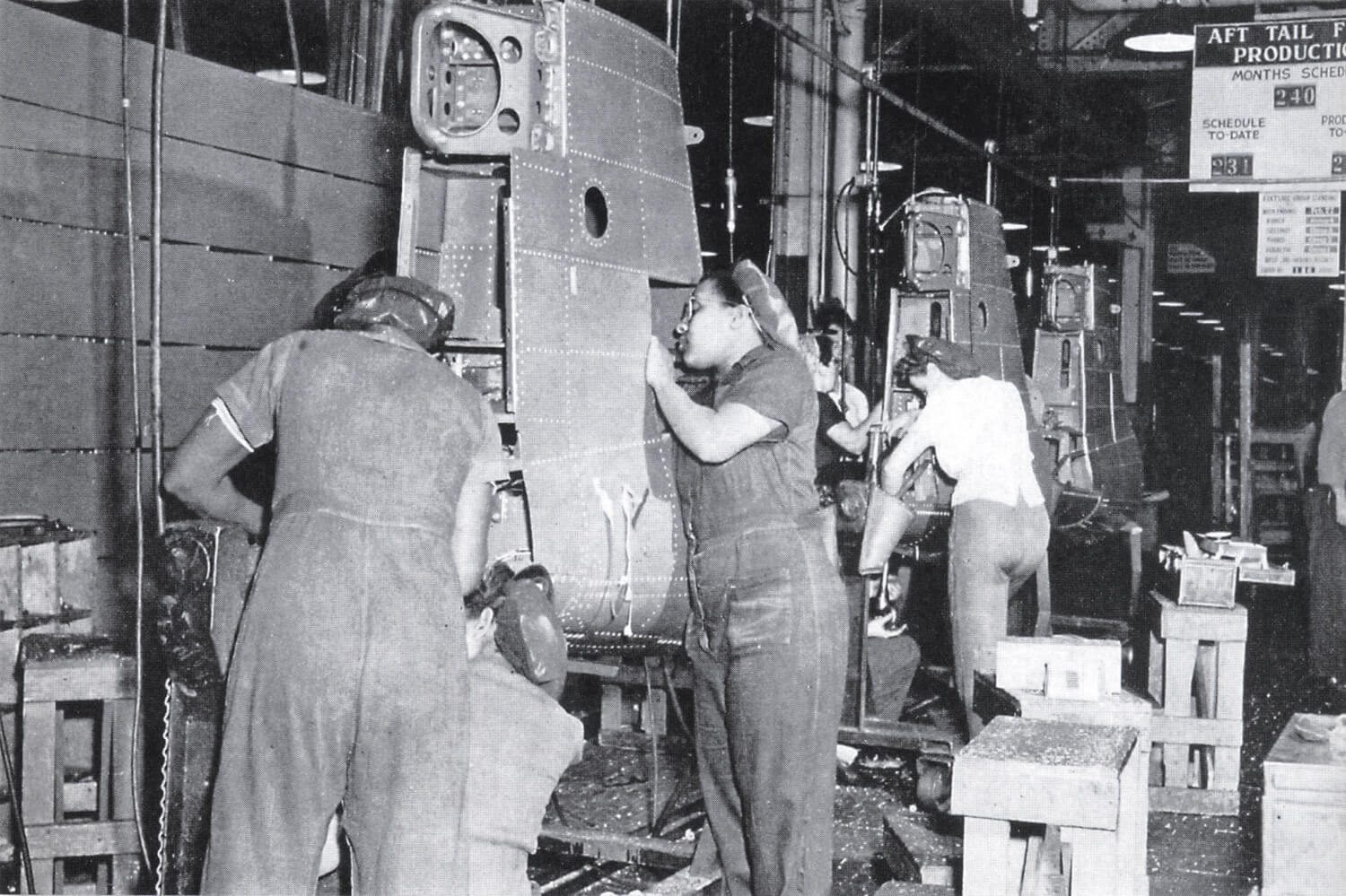

For much of the 20th century, the UAW and Big Three automakers were at the forefront of the major issues of the day. During World War II, the GM plant at Broening Highway was transformed into a defense factory, employing “Rosie the Riveters” to build aircraft fuselages as autoworkers went off to fight. After the war, the UAW became a key partner in the Civil Rights movement, supporting the integration of factories, the Freedom Riders, and voter registration efforts. UAW president Walter Reuther stood behind Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The union supported Cesar Chavez’s United Farm Workers. When Nelson Mandela was finally freed from South Africa’s Robben Island prison, he demanded a visit to local UAW in Michigan to thank the union, which had withdrawn its funds from banks with ties to country in 1978.

It’s a progressive history that White, Swanner, the former UAW Local 239 president, and other union members are proud of.

Atop the exact site where Baltimore steelworkers smelted the iron ore that built the Golden Gate Bridge and the Empire State Building, a second, 855,000-square-foot Amazon fulfillment center popped up last year.

For them, if there’s been a silver lining in the recent strike, it’s that it garnered front-page coverage and made the union relevant again. When GM dropped worker health benefits on the second day of the strike, public support tilted their way. Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Cory Booker joined striking members in White Marsh—as did Baltimore County Executive John Olszewski Jr. Union musicians from the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, who recently settled their strike, members of the Service Employees International Union, American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, United Steelworkers, and Johns Hopkins nurses, organizing with National Nurses United, also joined in solidarity.

Some observers think the UAW strike, its longest since 1970, may signal a broader comeback for unions on the heels of successful red-state teacher strikes in 2018. Overall approval for unions is up to 62 percent. “We are at an inflection point in terms of union support, which is at its highest levels in 15 years,” says Art Wheaton, professor of labor at Cornell University and an auto industry scholar. There is also an increasing public recognition that real wages have remained flat since 1973, despite a half-century of dramatic wealth and productivity gains, even during the current period of low unemployment. “Income inequality certainly is playing a role as well,” Wheaton says. In Maryland, notes 1199 SEIU vice president Lisa Brown, unions led the recent and successful “Fight for $15” and paid sick-leave campaigns.

vehicle production was halted for four years at Broening highway as "rosie the riveters" builT fuselages for U.S. Aircrafts during World war II. Courtesy of GM ARCHIVES

"I'm The big sister, that's my role, and they knew they could count on me to pay for a funeral or an emergency expense when it came up, because i worked at gm."

It was the basic chance to make a sustainable living that brought Barbara Travers and Karen Saulsbury to Broening Highway in 1972. There were few comparable opportunities for young black females, let alone mothers, and they were among the first women to join Local 239. “I started five days before she did,” Travers says with a laugh, gesturing to Saulsbury, as they walked the UAW picket line in late September. Each had 47 years when they were laid off. Both are outgoing, with quick smiles, and remain extraordinarily fit after nearly a half-century working on their feet. Travers started eight months after giving birth to twins. Saulsbury had a 1-year-old son when she began her career.

Travers added molding and trim at the end of the assembly line. Saulsbury locked steering wheels in place—60-plus an hour. Their GM union jobs certainly provided financial security, but also a degree of emotional stability for them and their loved ones. The jobs made an impact that has rippled through subsequent generations. “To provide for my family meant everything,” Travers says. “I helped my three children go to college. I have six grandchildren, three of them have graduated from college. A fourth is at the University of Maryland-Eastern Shore. The other two are in middle school.” She adds that she’s also the oldest of eight siblings.

“I’m the big sister, that’s my role, and they knew they could count on me to pay for a funeral or an emergency expense when it came up, because I worked at GM.”

Saulsbury’s son is in management at an East Coast flooring company, and her daughter is an OB-GYN doctor at MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center. Her oldest grandchild is in college in Florida and plans to become a doctor, too.

Neither Travers nor Saulsbury planned on retiring yet, and it’s still sinking in.

Sporting a Lamar Jackson T-shirt, Saulsbury gives Ray, a fellow UAW member, also wearing Ravens colors on this Friday, per Baltimore tradition, a hug goodbye as the picket line breaks up a couple of hours after lunchtime. “I’ll see you tomorrow,” she tells her longtime coworker. “Oh, my God. No I won’t,” Saulsbury says, suddenly catching herself. “We’re all wearing purple, and here I am thinking tomorrow we’re going to work our Saturday shift. Give me another hug.”