News & Community

A landmark is reborn in the birthplace of the American railroad.

By Lydia Woolever

Photography By Justin Tsucalas

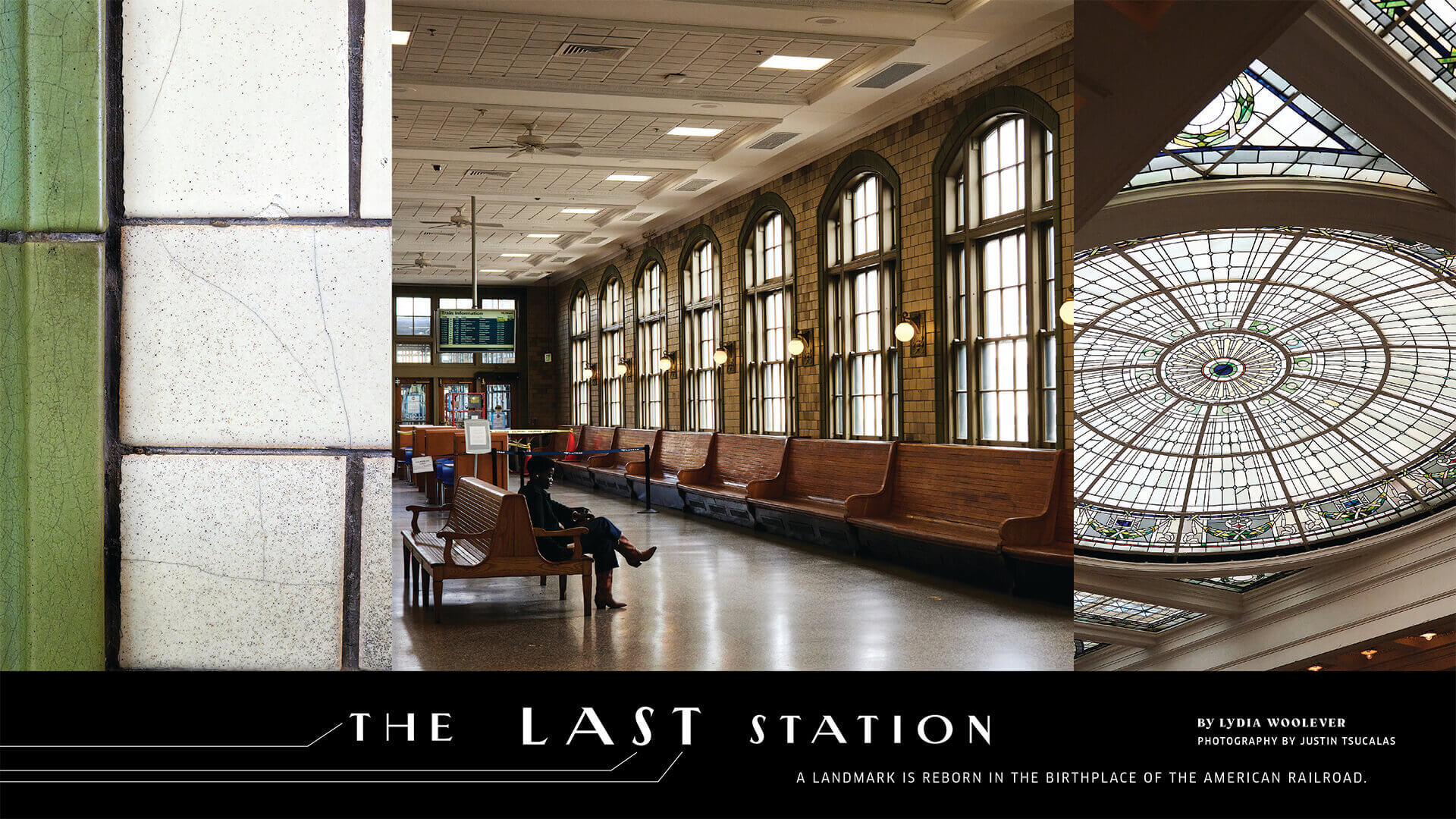

Opening Spread

Inside Penn Station; the

Tiffany skylight.

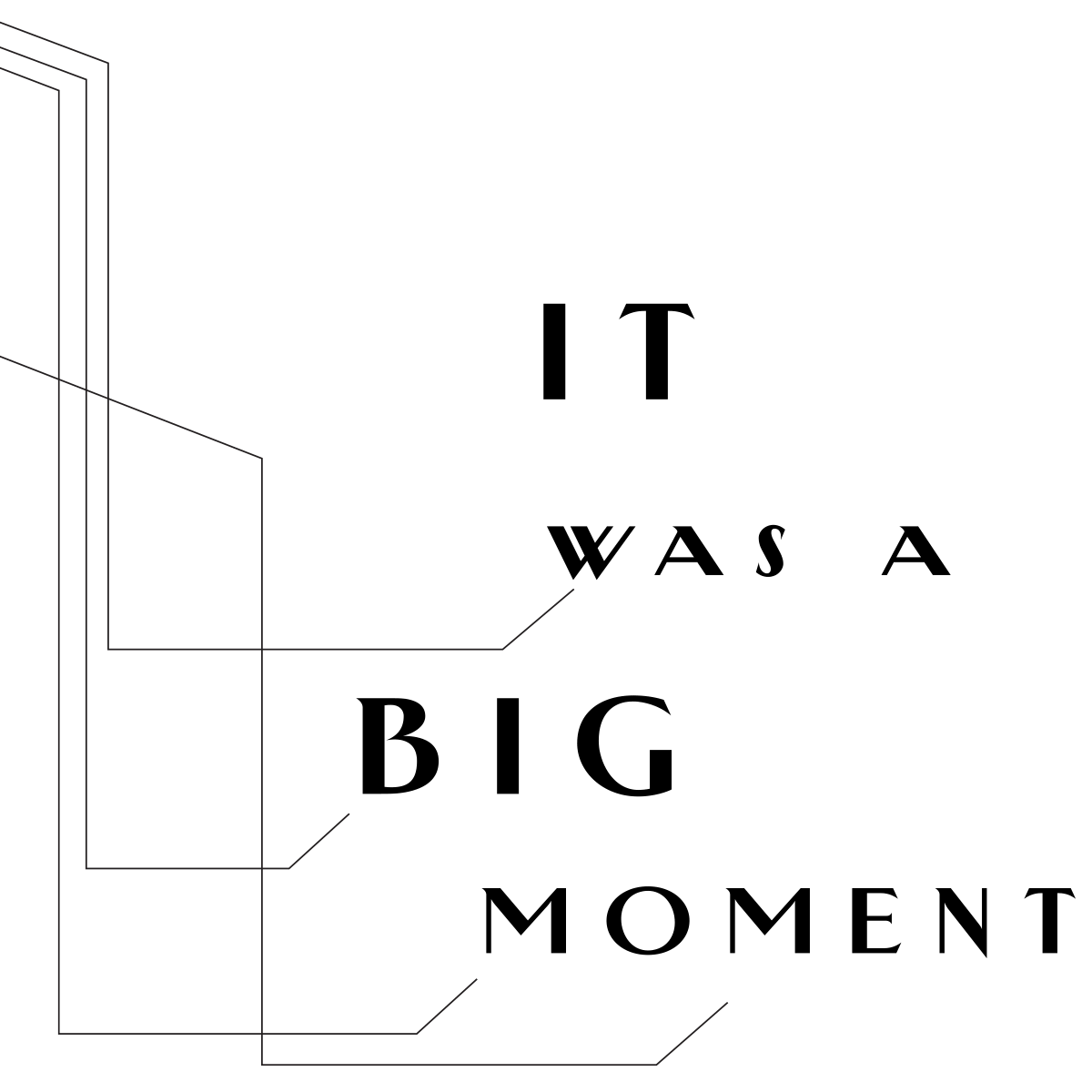

for Gamble Latrobe. When the new train station first opened its doors on North Charles Street in Baltimore, the 45-year-old native son had already spent a career climbing the ranks of the booming railroad industry, rising from an entry-level engineer in 1884 to the local head of the Pennsylvania Railroad—a position that made him the man of the hour on this Thursday evening, September 14, 1911.

Railroading was in Latrobe’s blood—his grandfather, Benjamin Jr., was chief engineer for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, helping to lay the company’s first tracks—but landmarks were, too. Considered one of the greatest architects in American history, his great-grandfather, Benjamin Sr., designed the likes of the United States Capitol and Baltimore Basilica, while his father, Charles, a Baltimore City engineer, can be credited for the Patterson Park Pagoda and the original bridges that crossed the Jones Falls.

Along that same waterway, Gamble now stood, tall in stature, with a thick mustache, in the halls of his own monument—a four-story Beaux Arts train station, decorated with ornate granite and marble finishes, that would carry out its first service tonight. For years, Latrobe had been a loyal advocate for the station’s completion, and now, when the wooden hands of the façade’s grand clock struck 8 p.m., it would become his official charge. “The building of the new Union Station on Charles Street may be regarded, to a great extent,” wrote The Sun at the time, “as a monument to him.”

Hours before the first train pulled in around 1 a.m.—a New York express bound for Washington, D.C.—some 5,000 people flooded through the oak doors of the arched entryways into what was then known as Union Station, and not because they were all travelers. The last station, built here in 1886, had been overcrowded, uncomfortable, and, at times, downright dangerous, with passengers crossing active tracks to reach their trains. Before that, the original structure, circa 1873, was little more than a wooden shed. The new Union Station was state of the art, it promised change, and after decades of complaints and a year of construction, residents were anxious to see inside.

Gamble Latrobe. 1916-1917 PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD YEAR BOOK, RAILROAD MUSEUM OF PENNSYLVANIA, PHMC

Latrobe led the crowd around the building, showing off the new ladies’ parlor, men’s smoking room, newsstand, lunch counter, dining room, telegraph and telephone booths, and, of course, the colorful skylights made of Tiffany stained glass, yielding expressions of awe and approval. After all, this was finally the finery fit for a major East Coast metropolis—not to mention the birthplace of the American railroad.

“There is not a better railroad station in Philadelphia, in New York, or in the country than this,” touted Latrobe to the press that evening, “and it all belongs to Baltimore.”

But much like Latrobe’s legacy, this sense of wonderment would soon fade. The public quickly resumed its grumblings about what we now know as Penn Station. It was still too small, too smokey, too far from downtown. Even that opening night had minimal fanfare—no bright lights, no ribbon cuttings, its four American flags already blackened by locomotive smoke.

And so it would go for the city and its station, with ups and downs not just in the immediate months and years that followed, but to this day—a century after Latrobe’s death (due in part to “hard work,” per his obituary).

If only he could see it now: his station once again on the verge of rebirth, this time with an even more ambitious vision—of not only improving travel in and out of Baltimore, but connecting the entire city.

Though the question remains: After generations of such promises, will it finally succeed?

Trains, buses, trolleys, and Model Ts at the station, circa 1926. COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE, Z24.1086;

A rendering of the redevelopment sits in a room on the upper floors.

I t’s clearly in need of some work,” says Chris Seiler, marketing director of Beatty Development Group, walking through the upper floors of Penn Station this past November.

Around him, layers of paint flake away from the walls, fading carpet peels back from the floor, rusted radiators lean lifeless in the hallway, and signs taped across scuffed doors read “temporarily out of order.” These rooms were once offices for railroad employees like Latrobe, but today, most travelers don’t know they exist, having sat vacant for decades.

Soon enough, though, they could be full of life again, or so hopes Seiler and the rest of Penn Station Partners, a master developer collaborative formed in 2017 between Beatty and fellow local real-estate heavyweight Cross Street Partners, who together will oversee the $150-million redevelopment of Amtrak’s eighth busiest train station. Before COVID, its Northeast Regional, high-speed Acela Express, and state-owned MARC commuter trains served more than one million passengers a year—a number that everyone is banking on them returning to, and then surpassing, in the years ahead.

In October 2021, a groundbreaking ceremony hosted local leaders holding shovels and donning hard hats. Behind them, a banner foretold of the historic station’s vibrant facelift. More impressive still, it showed that the drab parking lot across the tracks on Lanvale Street would soon be home to an ultramodern expansion—a glowing juxtaposition to the august yet austere flagship, which together could become the crux of a long-awaited renaissance, starting in its Station North neighborhood.

“This will transform Baltimore,” said Mayor Brandon Scott that afternoon. “It will change the lives of [Baltimoreans] for generations to come.”

For those of a certain age, it was déjà vu, having already seen at least two grand plans for such a revitalized transportation hub at this same location in recent history, both also hailed as the city’s great savior—ones that could heal broken infrastructure and bond fractured communities—only to watch them die on the vine instead.

Still, none have come this close.

“These projects move at a glacial pace,” says Seiler, staring up at the central skylight, trimmed in shades of blue and green. “But finally, we’re off to the races.”

Station North before highways, circa 1940. BALTIMORE CITY ARCHIVES

It’s no small feat, breathing life back into this 112-year-old landmark, its worn marble staircase and weathered wooden benches grooved with Maryland history. But scaffolding went up last February, and by fall, construction workers were busy bringing the building’s façade back to its original glory. Stone is being scrubbed. Masonry is being repointed. Windows are being repaired and the roof is being replaced.

For a while there, the old clock stopped ticking, but now it tells time again, looking out over Mid-Town Belvedere, Mount Vernon, and onwards south, toward Baltimore’s harbor, where the railroads once reigned.

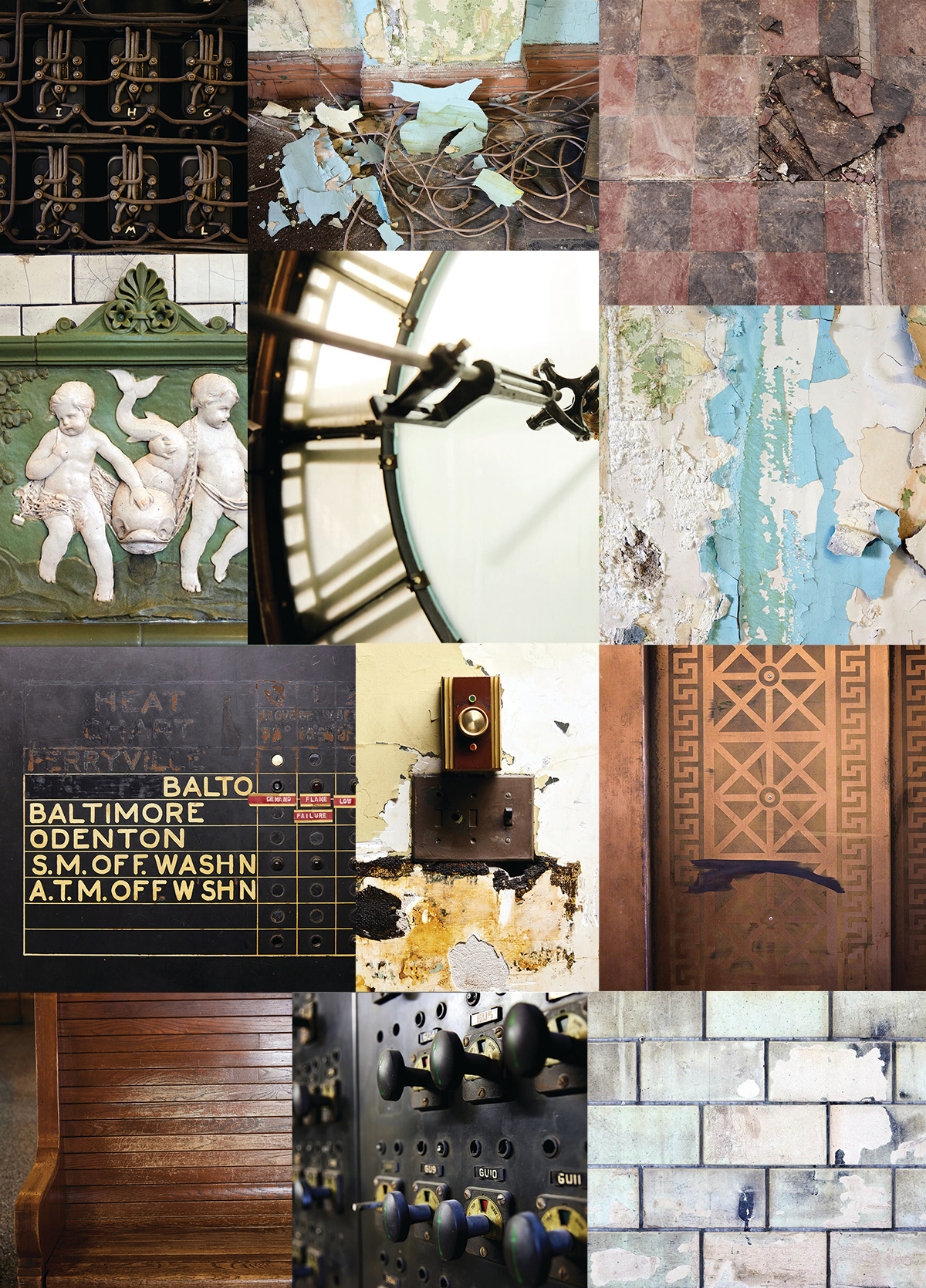

A miscellany of interior details before renovations begin inside the station.

I n many ways, it’s ironic that it has taken so long for Penn Station to get the love that it deserves. After all, this is the place where, just two miles southwest, the American railroad was born almost two centuries ago.

At the time, Baltimore was the second largest city in America, and while its inland port positioned it as an economic powerhouse, there was no major westward river, which other East Coast cities were using to build canals that would open new markets for trade.

But in 1826, a group of locally owned businessmen found the solution in a nascent technology being trialed across the pond in England. They pooled their money, and the next year, the state of Maryland chartered the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad—the first commercial railroad in all the United States.

“It was huge fanfare,” says Jonathan Goldman, curator at the B&O Railroad Museum, located in the company’s original Mount Clare Station on West Pratt Street in Pigtown. “After he set the first stone, Charles Carroll, an early investor and the last living signer of the Declaration of Independence, led a parade across Baltimore. Everyone went. There was music. It was a big to-do.”

The second station, built in 1886. COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE, PP107.75

A mix of iron and granite laid by Irish immigrants, the first tracks opened in 1830, carrying the first passengers to the first train station in what is now Ellicott City, and before long, they unfurled west, toward the Appalachian Mountains, and east, to the Baltimore harbor’s bustling docks, where industries rose up to meet them. In no time, new companies caught on and started sprawling across the city—and country—too.

“You can still see the tracks going through the streets in some places,” says Goldman. “It was the internet of the 1800s. Immediately everyone saw how fast it went, how predictable it was. They abandoned the canals and switched to railroads. And Baltimore was the epicenter of this new technology, for a while.”

The end of the Civil War ushered in an explosion of growth, as well as a ruthless age of industry rivalry, with B&O competitors including the Northern Central Railway, the Baltimore & Potomac Railroad, and its greatest adversary, Latrobe’s Pennsylvania Railroad, which bought up those other companies, and with them, vital economic passageways.

“Think of it like Google and Apple,” says Goldman. “They were big money. They were technology. They were infrastructure. They were commerce. They were travel. For all of human history, the speed limit was how fast a horse goes, which is eight miles an hour. The first locomotive was 13. A hundred years later, they’re more than 100. Just imagine how the world shrank. Lincoln sent troops to Gettysburg by rail instead of marching them from Washington. Electronic communication got developed for trains. Time got standardized for trains. It was transformational.”

It was during this time that the first Union Station was built in Baltimore in 1873, located below street level, just north of the flowing Jones Falls and south of the North Avenue city limits. The board-and-batten structure didn’t last long, replaced in 1886 by a more formal station, named, as in Washington and Chicago, in hopes of becoming a junction for both northern and southern railroads.

But even at a cost of $1 million, the new brick building was still a far cry from a modern amenity, with passengers infamously injured or killed along its tracks. It was the turn of the 20th century, and Baltimore had grown impatient for a dignified station befitting its booming city, ultimately feeling left behind by the railroad.

“It is probable that no city in the United States of the size of Baltimore . . . is so poorly provided with railroad terminals as is this city,” wrote a Sun editorial in 1907. “The company has been promising a new station . . . but the fulfillment of that promise is apparently as far away now as it was years ago.”

That is until 1910, when, under the direction of Latrobe, the old Union Station was demolished, and construction began on a grand new gateway for Baltimore’s future.

The cast-iron canopy; travelers linger in the marbled lobby.

S ome have called Penn Station an acropolis. Flanked by bridges on St. Paul Street to the east and North Charles Street to the west, the 112-year-old train terminal sits at a 45-degree angle on a hillside above the rocky banks of the Jones Falls, as if watching over Charm City.

Time has kissed its steel-framed façade, designed by New York architect Kenneth Murchison and built by the local J. Henry Miller Construction Company, but the building remains a classic beauty, full of European flair and rich details, from its soaring Roman columns, gilded windows, and ornamental roof lines to its intricate cast-iron canopy scalloped in emerald-green glass.

“It was very much meant to be a civic monument,” says James Smith of Quinn Evans, the renovation project’s associate architectural firm. “Penn Station has had a rough life, many parts have been patched, repaired, and replaced over the years, but it remarkably retains its character.”

Inside, terrazzo floors lead travelers into a lobby wrapped in Sicilian marble and dappled by that iconic trio of domed skylights framed with whimsical sconces. Past fluted columns into the main concourse, cream and olive Rookwood tiles line the walls, amidst brass fixtures and elegant benches that curve with the shape of the room above the platforms below.

The Charles Street bridge, circa 1911. MARYLAND DEPARTMENT, PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION: L418

Against this backdrop, it’s hard to say whether the public’s grievances, aired after that 1911 opening, were valid or out of spite. It didn’t help that an even grander Pennsylvania Station had just opened in New York City, hailed as an architectural wonder with seamless service, and soon, ideas for Baltimore improvements were bandied about—relocating near City Hall, adding a rooftop airport, creating a superstation with the B&O.

“That such a vast Union Station is needed is, of course, sheer nonsense,” wrote H.L. Mencken in a 1928 Evening Sun.” “I can recall only three or four occasions when it was uncomfortably crowded—and then it was crowded, not by passengers, but by idlers horning in to gape at [Calvin] Coolidge, or Jack Dempsey, or the Prince of Wales, or some other such magnifico.” For a while, it remained as it was.

The north side of Penn Station, overlooking the tracK.

N ot train travel though, which continued its golden age through the first half of the 20th century. It was a period of peak innovation, with diesel locomotives and electrified tracks introduced in the 1930s, and fast, fancy Pullman cars offering the latest and greatest luxuries, from air-conditioning to dining cars dripping in oysters and martinis. World War II provided another boost, as 98 percent of servicemen and women were deployed by rail, including many out of Baltimore. A temporary USO lounge took over the east side of what had since been renamed “Pennsylvania Station,” while blackout paint, applied to the lobby skylights to fend off enemy war planes, stayed in place until the 1980s.

The station’s old Savarin restaurant.Courtesy of Baltimore Museum of Industry Archives

But by the 1950s, the rise of automobiles and the advent of airlines would precipitate the crash of private railroad companies. The B&O had already been sold, and in 1968, the Pennsylvania Railroad merged with the New York Central, only to give up the ghost two years later via bankruptcy—then the largest of its kind in U.S. history. It was the end of an era, and also the beginning of a new one.

“That’s when it all comes to a head,” says Johnette Davies, historic preservation manager for Amtrak. “Then you’ve got the inception of Conrail, and the creation of Amtrak.”

With an act of Congress in 1970, Amtrak was born as a bailout for American train travel. Inheriting much of the once-private track between Washington and Boston, the country’s government-owned railroad company also took over stations located along what would become its Northeast Corridor, including Baltimore’s Penn.

At this point, Latrobe’s pride and joy had fallen into true disrepair, with dated cars used for deteriorated service along graffitied tracks, and minimal maintenance done inside. Penn Station was seen as a reflection of its surrounding neighborhood, which was riddled with blight. The Jones Falls now trickled out of view, buried beneath the new I-83 Expressway.

In one of his earliest urban revitalization efforts, Mayor William Donald Schaefer did his best to spruce up the joint—from a deep clean to fresh landscaping—and promoted the then-novel concept of transforming the station into a “multi-modal” transportation hub, which, post-oil embargo, would create a one-stop shop for all forms of transit, improve travel around Baltimore, and serve as a waypoint for other cities, even possibly luring residents from D.C.

Little came of it, whether for lack of funding or loss of interest. But by the 1980s, the state’s MARC commuter railway did begin service along the Amtrak tracks, and in 1997, the Light Rail, linked to the BWI Airport, eventually joined them at Penn Station. Today, five bus lines, plus the Charm City Circulator, now stop a stone’s throw away on Charles Street, but the subway never made it, nor did an axed Greyhound terminal.

If Schaefer’s vision were to become a reality, wrote The Sun in 1975, it “will give Penn Station a second lease on life. It will become once again a functional asset to the life of Baltimore.”

The plaza’s Male/Female statue; passengers board a MARC train on the evening commute.

B ill Struever doesn’t remember the first time he visited Penn Station, but when he moved to Baltimore in 1974, the budding developer knew that this “most civilized way to travel” was an indisputable asset for his newfound city.

Michael Beatty and Bill Struever of the Penn Station Partners development team.

In the decades since, Struever, now 70, has invested heavily along the railroad’s tracks through East Baltimore, from repurposing several 19th-century structures with his Cross Street Partners development firm to helping his nonprofit American Communities Trust spearhead the Last Mile Park project, which will use art to illuminate the dark underpasses along the final northern stretch leading up to Penn Station. It only makes sense, then, that he would set his sights on the landmark itself.

“It’s been a long time coming,” says Struever, who came onboard the redevelopment project in 2017, five years after Amtrak first tapped Beatty to conceive a plan for the aging train station, “but good things take time.”

Working with a site on the National Register of Historic Places, the developers must follow strict state and federal preservation standards for every inch of the original “headhouse,” where exterior work, including dramatic new lighting, should be done by fall. A rejuvenated plaza is also being envisioned for reduced car traffic with pedestrian walkways, bike and scooter parking, and designated bus zones. The fate of its polarizing Male/Female statue, once described by City Paper as “Baltimore’s kinkiest artwork,” remains to be seen; the final call will be up to city government.

Come spring, they’ll move indoors, where any remnants from the last major renovation, circa 1984, will be removed, and all other historic details will be meticulously refurbished. Currently home to a newsstand, Dunkin’ Donuts, and the Java Moon Café, the east and west wings will be reimagined for new restaurants and retail, with priority placed on local businesses. The upstairs will be gutted for future office space.

Eventually, the north wall will be blown out and the construction of a bridge across the tracks to the Lanvale Street parking lot will lead to a new concourse for Amtrak. With an airy, luminous design by the Gensler global architectural firm, it will also include access to a brand-new Acela platform and, one day, a skyscraping complex for potential commercial and residential use, encouraging visits for more than just catching trains. In fact, the developers hope you’ll stay awhile, with a glassy south wall overlooking the old station and the tracks below showcasing “train as theater,” says Gensler design director Peter Stubb, as well as a “window to history.”

“Everything is going to be right here,” says Struever, crediting the project’s rollout in part to the city’s late Congressman Elijah Cummings, whose public persistence undoubtedly inspired Amtrak’s $150-million investment. The total bill could cost at least $400 million, to be covered by a mix of sources—federal, state, or private dollars, grants, tax credits, Opportunity Zone funding—with an optimistic completion date of 2025.

It coincides with a nationwide effort to reinvigorate America’s flailing rail system, which narrowly avoided a freight strike before Christmas, and whose passenger service is still recovering from COVID. With a significant lift from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, passed by lifelong locomotive-lover President Joe Biden, Amtrak’s $75-billion overhaul will include an all-new Acela fleet, upgraded Northeast Corridor infrastructure, and, eventually, the $4-billion replacement of the 150-year-old B&P Tunnel in West Baltimore—an infamous bottleneck to be renamed for Maryland abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who escaped slavery by train via the harbor’s old President Street Station. The company hopes to double ridership by 2040. MARC is likely to benefit, too.

But the country’s transit woes are not limited to train travel.

“A mess,” “a disaster,” “on the verge of collapse.” This is the reputation of public transportation in the United States, with transit long passed over in favor of roads that only induce more traffic. And yet studies show that every dollar invested into such infrastructure yields a $4 economic return to local communities, while also providing increased access to jobs, goods, and services for its residents, plus significant reductions in greenhouse-gas emissions in a time of climate change.

A rendering of the station expansion. COURTESY OF GENSLER

Meanwhile, a neighborhood’s service shortcomings correlate with lower incomes and higher rates of unemployment, and in Baltimore, where most riders are people of color and commute times rival gridlocked Los Angeles, a disjointed transit system—including an isolated subway and slow-to-grow bike lanes—continues to perpetuate inequalities.

Like Schaefer a half-century before him, Struever sees Penn Station as a multi-modal transportation hub that could uplift his struggling city, especially if his and Beatty’s efforts are combined with a stop on the new north-south, city-county transit corridors being studied by the Maryland Transit Administration, or the prospective east-west MARC extension to the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center in East Baltimore.

“You can talk all you want about Maglev—the Northeast Corridor is happening,” says Struever, referring to the futuristic magnetic-levitation trains that would move passengers between Baltimore and D.C. in 15 minutes. “We have the most transit-friendly administration in history in Washington right now, and you bring transit up to [Governor] Wes Moore and he starts bubbling with ideas, and then you have Amtrak well along the way. Shame on us if we don’t use Penn Station as a launchpad.”

And part of its promise lies in its very location.

The station’s circa-1911 clock; scaffolding awaits a grand reveal.

I t wasn’t that long ago that the area now known as Station North was considered the end of the earth for Baltimoreans. In the early 1800s, the city’s northern edge along “Boundary Avenue,” aka North, was little more than a collection of country estates. With time, it evolved into an axis of education, industry, and culture, and as the city stretched northward, it left behind landmarks like the circa-1917 Parkway Theatre to live on as tethers from past to present.

Today, the Charles North, Greenmount West, and Barclay neighborhoods that make up Station North are once again in a state of transition, with change then and now coming in fits and starts, and for decades its reputation swinging between “rough-around-the-edges” and “up-and-coming.”

Now located in the geographic heart of Baltimore and designated the city’s first Arts & Entertainment District since 2002, it’s a creative crossroads where an eclectic mix of veteran businesses like Tapas Teatro and Club Charles mingle with newcomers like the Le Comptoir du Vin bistro, The Royal Blue bar—named for a beloved B&O passenger train—and The Parlor pop-up arts space in a former funeral home, with its namesake station always looming large in the distance.

“For as long as I can remember, there’s been talk of this grand Penn Station redevelopment, and then it just doesn’t happen,” says Kathleen Lyon, second-generation owner of The Charles Theatre. “The neighborhood is holding its breath but feeling good. There’s this on-the-cusp feeling—of hope and optimism for new beginnings. What do they say? From the rubble, things rise.”

Still, Station North has a 42-percent commercial vacancy rate, hamstrung by retail turnover and speculative landlords waiting on urban renewal of neglected blocks to yield higher prices. The focus now is on filling in the gaps, which would be a boon to business owners like Lyon, who already benefits from the station’s commuters. For starters, six unused Amtrak-owned properties are currently slated for redevelopment along the tracks.

“Say whatever you want—density brings people, and density brings economic opportunity, and that’s a good thing,” says Jack Danna, director of commercial revitalization for the nonprofit Central Baltimore Partnership. “There’s great potential in creating something that brings these communities together.”

Which they have not been, for a long time, and by all accounts, Penn Station, trapped in a snarl of busy thoroughfares, is the island between them. To the north, the 1.5-acre parking lot on Lanvale Street serves as a barrier to its umbrella neighborhood. To the south, I-83 barricades Mid-Town Belvedere, Mt. Vernon, Bolton Hill, and Johnson Square—though proposed improvements to the Oliver Street promenade aim to better connect the station’s plaza to MICA and its Mt. Royal Light Rail station.

“We’ve been a city of two cities for my 49 years here,” says Struever, lamenting the loss of the Red Line rail project between East and West Baltimore, which secured $900 million in federal funding before being unceremoniously slashed by Governor Larry Hogan. “This is the ultimate opportunity to bring our city together. It is truly the one place where Black Baltimore, white Baltimore, city, suburbs, rich, poor, north, south, east, west all meet.”

But attempts at weaving together disparate parts of the city have been known to tie Gordian knots. Revitalization often means gentrification, which often means displacement of those low-income residents who benefit most from enhanced transit. Equitable development of Penn Station could look like commitments to small-business tenants, living-wage job opportunities, and solutions for the surrounding food deserts, says Lauren Kelly-Washington, president emeritus of the Greenmount West Community Association, who’s been involved in the project’s community outreach, with a third public meeting expected this spring.

“You have a double-edged sword—if you own a home and want to pass on that generational wealth, an increase in value is not necessarily a bad thing, but as rents go up, that changes who can live here, and how will subsidized housing be affected?” says Kelly-Washington. “There’s concern, of course, about gentrification, but people are ready. The area deserves this level of investment. This is the center of Baltimore. And Baltimore needs to pay attention to its center in order to be a shining beacon of the East Coast.”

Video of a train arriving today. Video by Justin Tsucalas

A rika Davenport grew up near Penn Station, living just up the street on Guilford and Lorraine avenues in Charles Village. In the summertime, her grandfather, a firefighter with Engine Company No. 52, would take her on the newly formed Amtrak line to see the sights in New York City.

“I was always fascinated by trains,” says Davenport. “I have a cousin who is a conductor, an uncle who was an electrician, an aunt who worked in payroll—and all they talked about was working the railroad.”

After a career as a court clerk, she applied for an Amtrak job in 1999, coming onboard the first-class car of the Northeast Regional’s then-new Acela trains—at the time a 16-hour, 43-minute roundtrip between D.C. and Boston.

“I worked it every other day,” says Davenport. “Railroading taught me a lot about myself as a young woman. I enjoyed interacting with people and I would sometimes sing ‘New York, New York’ to the passengers. After 9/11, it became part of my routine.”

Now, at 55, Davenport works in customer service, navigating the evening rush hour in Baltimore five days a week. Dressed in a tailored blazer and white blouse with silver earrings, she breaks out in a playful smile when sharing that she’s referred to as “the C.E.O.” by commuters and colleagues.

“It’s not just selling tickets—we’re mothers and sisters, we’re therapists,” she says, having helped travelers with dementia and always on watch for human trafficking. “I treat everyone like they’re at my house. You want them to come back again.”

Throughout renovations, Penn Station will do its best to run business as usual, with dozens of trains rolling in and out morning and night. Baltimore is no longer the tangle of tracks it once was, but after a lifetime of false starts, the city might finally get the station that it has dreamed about, one way or another, for over a century—the last of its local kind.

Only time will tell what that will mean for the future.

“I’ve been all over this station, and whichever way you look at it, there’s a lot of history,” says Davenport. “I’m always in awe when I stop and think about all of the people who’ve passed through here.”