News & Community

Bleeding Black & Orange

From Brooks to Tejada, 50 Glorious Years of Orioles History

Baseball teaches us many things. It teaches us how to win gracefully and, alas, how to lose gracefully, too. It teaches us that it ain’t over ’til it’s over. It teaches us that sometimes a simple game can fill a grown-up with childlike joy. It teaches us loads of patience—patience during a rain delay, patience during a losing streak, patience as we watch a hitter step into the batter’s box and out of the batter’s box . . . and step back in again. But in the end, it mostly teaches us about loyalty. For 50 years, the Orioles have been a team we, as a community, can proudly remain loyal to. So for this, our special 50th anniversary tribute to the O’s, we decided to look back and look forward. Our Orioles timeline highlights the ups and downs of Orioles past (Brooks! Palmer! $#@!* Jeffrey Maier!) Our interview with Rafael Palmeiro welcomes back a sweet-swinging fan favorite. In The Other Iron Man, we affectionately profile Ernie Tyler, the oldest living—and hardest working—ball “boy” in the game. And finally, we sit down over banana cream pie with the new navigators of the Orioles’ future: Jim Beattie and Mike Flanagan. Judging from what these two have to say, we think our loyalty (and patience) is about to be rewarded again.

On the night Cal Ripken played his final game, the Orioles held a pre-game ceremony honoring the more famous “Iron Man” for his contribution to Baltimore baseball. In his speech, Ripken thanked those that had helped and inspired him along the way. He called Ernie Tyler on the field and presented him with a Ripken game jersey mounted in a Cooperstown-style frame. Cal inscribed the front: “Ernie, We both know who the real Iron Man is. You’ve amazed me for years. Stay Healthy & Keep Going. Cal.” Tyler loves to challenge the phrase, “We both know who the real Iron Man is.” “You can take that two ways, you know?” he says with a chuckle.

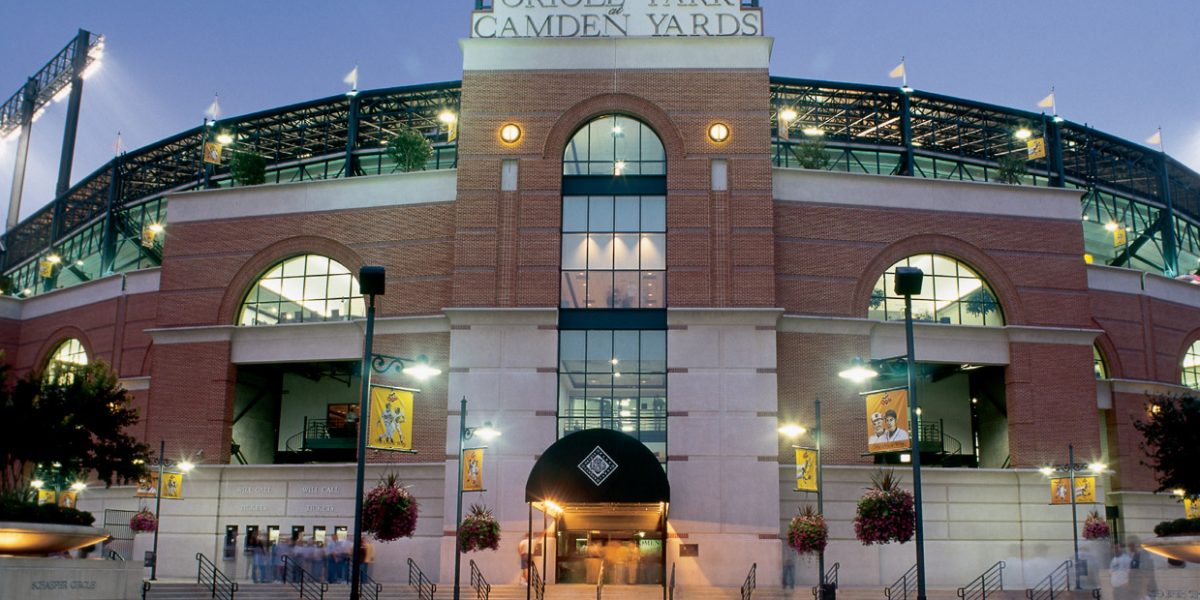

Sitting in his long narrow office under the Camden Yards stands behind home plate, Tyler rubs the gray Delaware River mud—the official mud used by major league baseball— on one of the 80-some baseballs he prepares for each game. The mud is slathered on so that the pristine white ball doesn’t glare in the light. Tyler explains how another ball boy’s gaffe helped him get his job.

“It was 1960,” he recalls. “I was working as an usher at the time. I knew some people that worked with the club, and one of them approached me because the previous fellow that gave the balls to the umpires had touched a ‘live ball.’”

Touching a “live ball”—or a baseball still in play—is a cardinal sin in the world of pro ball. The ball boy was shown the door. Tyler, hardly a boy himself at that time (he was 34), was asked to do the job.

Tyler works the ball as he talks—rubbing the baseball until it has a uniform color, then rotating it between his hands as he looks for defects. The work is meticulous, but it has the easy, inevitable feel of a well-practiced ritual. At this point,

Tyler could check for ball defects in his sleep. “I wouldn’t want anything less than a Major League quality ball finding its way into a game,” he says. “There seems to be a lot more defective balls now and most of the defects don’t show up until you work with the mud.”

In Tyler’s office, a small television sits on a table replaying the previous night’s game. On his desk is a Plexiglas case containing each phase of a baseball’s construction, from the rubber core to the stitching. He takes that exhibit with him when he makes public appearances on behalf of the Orioles at schools, nursing homes, and the Babe Ruth Museum. The walls are lined with large color photos of various umpire crews.

The umpire’s room and Tyler’s office adjoin each other, a necessary convenience since Tyler is not only the ball man, he’s also the umpire attendant—the person who ensures that all of the umpires’ needs are met: their shoes polished, their allotment of game-day tickets waiting at Will Call, and their shelves stocked with chocolate, aspirin, magazines, and beverages.

“They consider me one of them,” Tyler says proudly. Indeed, Joe Brinkman, the silver-haired umpire who has spent 31 years in the majors, remembers his first-ever Baltimore Orioles game for two reasons: “Brooks Robinson hit a three-run homer and I met Ernie Tyler.”

Adds Brinkman: “When I come to Baltimore there are three things I look forward to: crabs, crab cakes, and seeing Ernie.”

Ernie Tyler grew up in the Peabody Heights neighborhood, close to the Baltimore Museum of Art. He attended St. Phillip and James elementary school, then Mount Saint Joseph High School. The old Oriole Park— on 29th Street and Greenmount Avenue— was a short walk from Ernie’s house.

When he was in high school, Tyler got a job as a ball boy. Not behind the plate, but in foul territory down the lines. The job back then included shagging fly balls during batting practice. The only pay was the reward of watching the game for free from field level.

“And I was happy being in the park, just being around the game. I still am,” says Tyler, placing the baseballs into the large blue sack he will carry onto the field for tonight’s game.

In 1942, when one of Tyler’s neighborhood friends was killed in the war, Tyler and five of his buddies enlisted. He was sent to radio school and his first assignment was with the British Royal Air Force, based in Oran, Algeria. He was then assigned as a crewmember of a B-52 Bomber that flew raids over Europe as part of the Army Air Corps, precursor to today’s Air Force.

He’s loath to discuss his experiences in the war.

“How many guys do you know that want to talk about their war experiences?” he says bluntly. “It was something that had to be done.”

Tyler was stationed in North Africa when he met his wife, Juliane, a French girl who was living with her family near the base. “Some of the guys I worked with were musicians and we set up a dance hall,” Tyler recalls. “Local girls would come to the dances with their parents as chaperones. I spoke some French, and [Juliane’s] folks invited me to their house for dinner on a regular basis. This went on for two years, and I actually got a six-month extension of duty when my time was up because I didn’t want to leave her.”

Ernie and Juliane were married in l944. Their union has produced 11 children and 37 grandchildren. Three of their daughters have worked for the Orioles in the ticket department. All five of their sons served as batboys at various times, and currently sons Jimmy and Fred are employed by the ballclub as clubhouse managers; Jimmy for the home team, Fred for the visitors.

Neither has missed a day of work since they started.

Fred credits his father for instilling such a strong work ethic in his children.

“Showing up is one thing,” says Fred, who was the All-County shortstop in Maryland when a player named Cal Ripken from Aberdeen was the All-County pitcher. “But look out at [my father] in the 10th after the rain delay and watch him.” For night games, Tyler arrives at the ballpark sometime around 11 a.m. and, on average, gets home to Forest Hill sometime around 1:30 the following morning.

MUSES FORMER ORIOLE FIRST-BASEMAN BOOG POWELL:

“WHAT WOULD BALTIMORE BASEBALL BE WITHOUT ERNIE TYLER?”

With extra innings the day is even longer. That, notes Fred,

is what a work ethic is all about. But Tyler downplays his hard work—and his streak— much the way Cal Ripken did his. “I just do my job,” he says matter-of-factly. “Sure, there were nights when I didn’t feel good, but there was never a reason to take off, or I would have. Look, if you have a job you go to work if you can . . . I didn’t set out with the idea of a streak, any more than Cal did. It just happened. I didn’t think about it much until game number 2,500 when the ball-club presented me with a watch. Up until then nothing much was made of it.”

For the record, on September 14, 1991, the Orioles stopped their game with the Cleveland Indians in the sixth inning and Cal presented Mr. Tyler with a watch on behalf of the club.

A few years later, when the Orioles played the Detroit Tigers on April 9, 1998, it was Tyler’s 3,000th consecutive game. Governor William Donald Schaefer sent him a congratulatory letter. In honor of that same milestone, Orioles owner Peter Angelos gave Tyler an all expenses paid trip to Paris, where Tyler and his wife visited her family.

“It was a kind thing for Mr. Angelos to do,” he says.

Tyler’s backless stool on the field sits just behind the visitors’ on-deck circle, exactly 58 feet from the plate, and dangerously close to the action. There have been countless near misses, but only twice has a ball left a mark. He remembers each vividly.

Late in the 1966 season, Steve Barber fouled off a pitch that struck Tyler in the right forearm before denting the fence that separated the playing field from the fans. That ball left a permanent reminder of its fury on the fence and on Tyler, who carries a marble-sized knot on his right forearm where the ball struck him.

The other close call came in 2001, when Delino DeShields fouled off a bunt attempt and the ball hit Tyler just below the left kneecap. After the game he went to the team trainer.

“The ball left stitch marks it hit me so hard,” says Tyler rubbing the knee as if stroking away remnants of pain. “But, I was very lucky. The trainer said an inch or two higher or lower and the streak would have been over and I would have had a serious injury.”

But the biggest threat to Tyler’s record of consecutive games came from something a little more serious than a baseball ding. In January 1995 he was diagnosed with liver cancer.

The pain started in the latter part of 1994 season. Tyler felt so poorly that he had to have one of his sons help him with his pregame duties. Never one to dwell on discomfort, he delayed seeing a doctor. Finally, in January, l995, he went to Fallston General Hospital, where a radiologist detected a small abnormality and sent him by ambulance to Johns Hopkins for further tests.

“It was a Friday night. The doctor told me I had liver cancer and that I could wait for a little while and take care of whatever business I needed to tend to, or he could operate on Sunday and have me ready for Opening Day,” says Tyler.

Needless to say, a team of surgeons operated that Sunday. They removed approximately half of Tyler’s liver.

Tyler rehabbed by walking as much as possible at the White Marsh Mall. He went to Florida for spring training, but did not work for the club as he had previous springs. “I was still tired a lot,” he says.

But true to the predictions of his doctors, Tyler was back on the field for Opening Day, 1995, and the streak continued.

“I can’t see me leaving this job unless I get hurt or have some serious illness,” he says. “I’d be a fool to leave a job I love so much. One of the reasons I’ve lasted this long in this job is because I treat people like people. You treat them the way you want to be treated and everything else works out. I love everything about the job, I can’t imagine anything better.”

The Other Iron Man

In 43 years, Orioles “ball man” Ernie Tyler hasn’t missed a single day’s work.

By Howard Hart

On September 21, 2003, a member of the Baltimore Orioles worked consecutive game number 3,982. There was no parade. No post-game ceremony. No fanfare. And that’s just the way “ball man” Ernie Tyler likes it. In 1960, when Tyler’s streak started, Dwight D. Eisenhower was president, television was black and white, and Paul Richards was managing the Orioles. Gasoline was 30 cents a gallon, phone calls were a dime, and the Birds started a shortstop named Ron Hansen who would go on to win Rookie of the Year honors in the American League.

Not included in Tyler’s official streak are the three World Series appearances, numerous playoff games, and his work for the two All-Star games held in Baltimore. Neither, for that matter, are his games as an usher. (Tyler start-ed working for the Orioles as an usher at the l958 All-Star game.) Add all those absence-free games up, and the streak is even longer.