News & Community

Are We Still Charm City?

We wrestle with the complicated legacy of our town’s most enduring nickname.

Baltimore has been a city of many nicknames: the moth-eaten “Monumental City,” the wishful “City That Reads,” the disparaging “Mobtown,” and the truly disheartening “Bodymore.” And, of course, to this day, there is still “Charm City.”

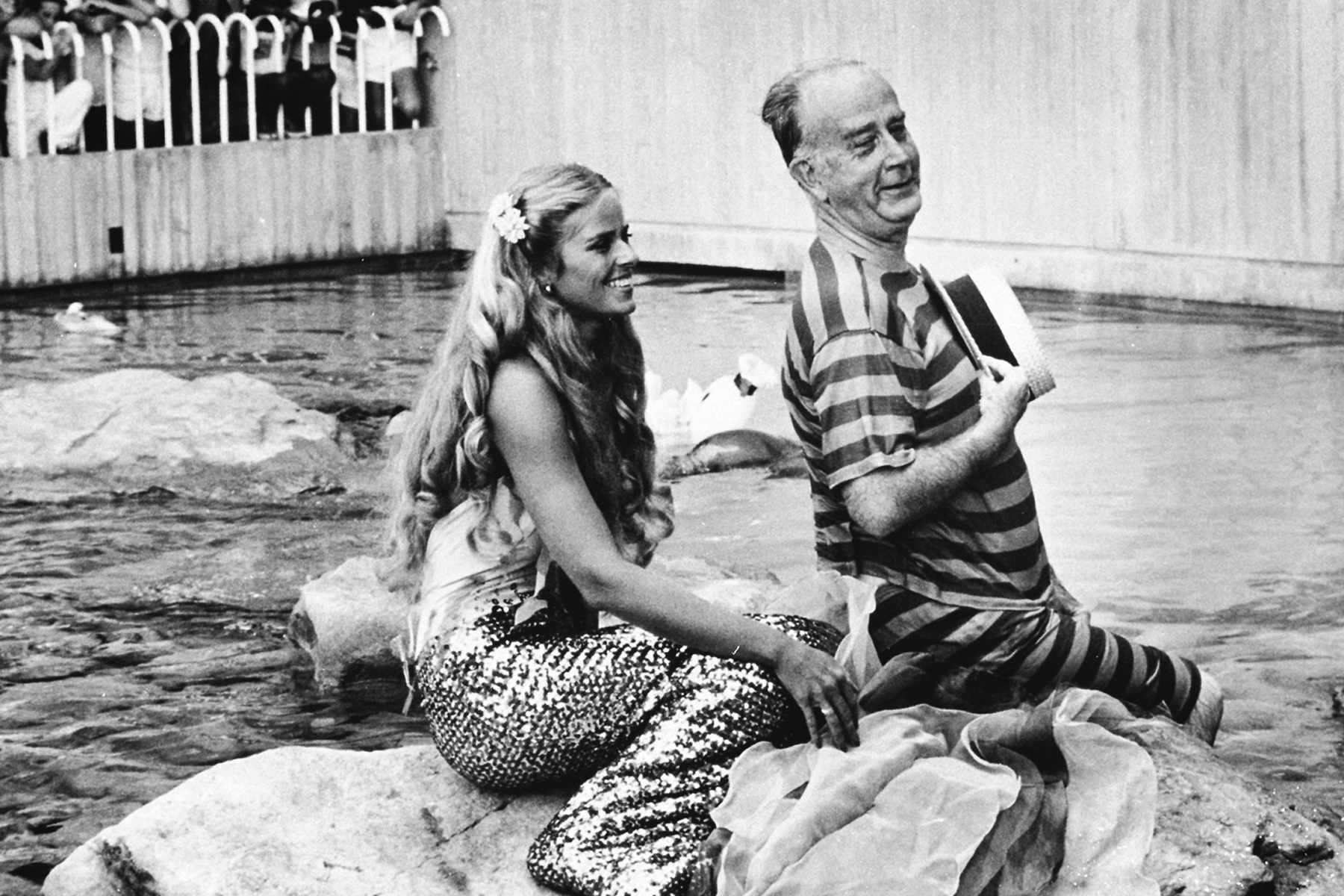

William Donald Schaefer at the National Aquarium.

Over the years, “Charm City” has become so much a part of this town’s branding that it’s hard to remember a time when it didn’t exist. Although the word “charm” was applied to Baltimore in some of H.L. Mencken’s early-20th-century writings, the moniker is only 44 years young.

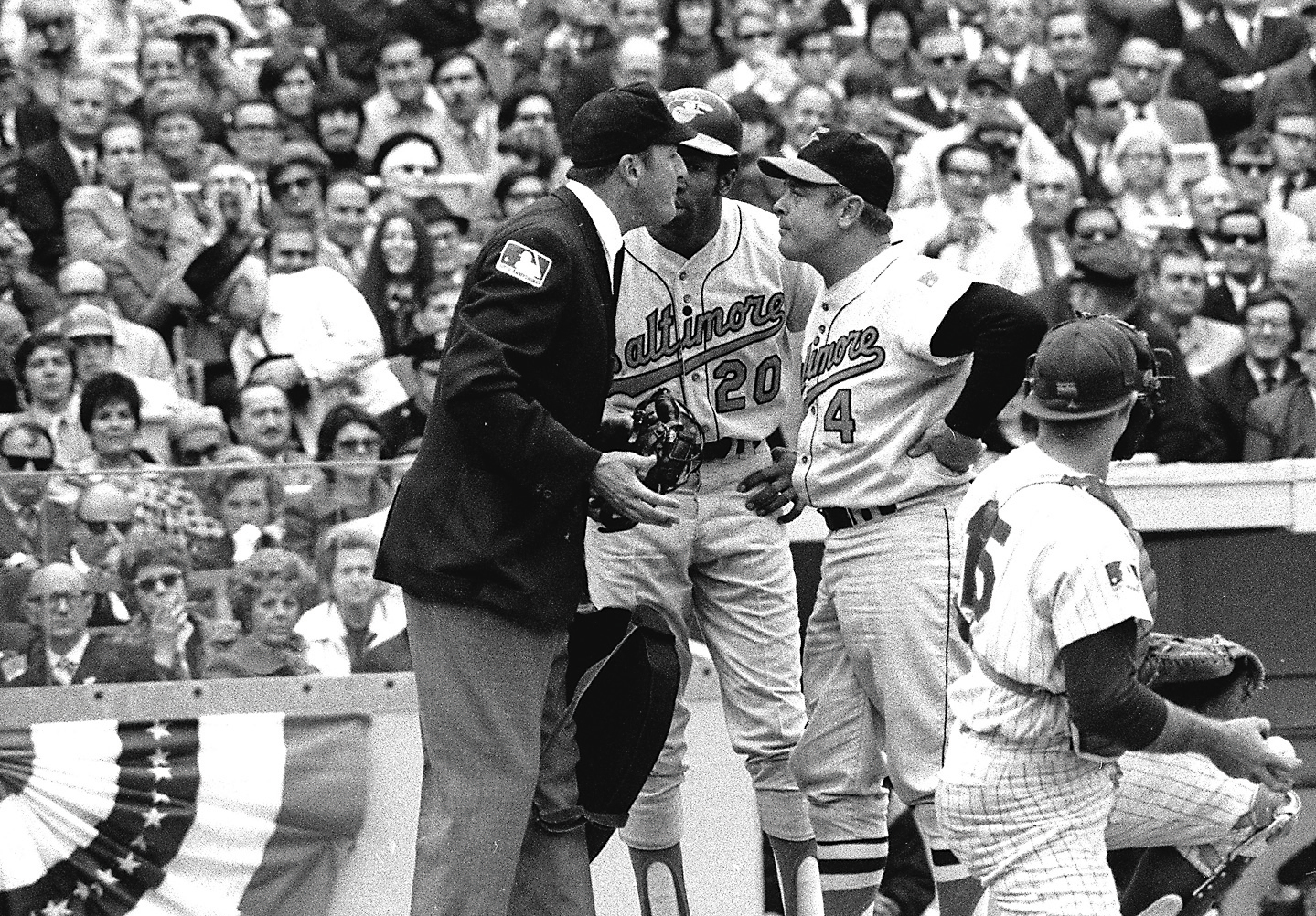

As many millennials and transplants won’t recall, it was born out of a marketing campaign under the resourceful Mayor William Donald Schaefer. In the late 1960s, toward the end of his first term, in the face of both suburban exodus and the death of our industrial backbone, Baltimore was dubbed by Sports Illustrated as “A Loser’s Town,” “Yesterday Town,” and “The Last Frontier.” (Talk about nicknames we didn’t want to stick.) Schaefer knew he had to do something about the city’s image—and fast.

And so with his can-do attitude, and fresh off the success of the City Fair, “Charm City, U.S.A.” was born during a heat wave in the summer of 1974, with advertisements gloating about the city’s hidden treasures gracing the pages of The Sun and The New York Times. “Baltimore has more history and unspoiled charm tucked away in quiet corners than most American cities put in the spotlight,” the ads read alongside a photo collage of crabs, marble steps, historic landmarks, and the fiery Blaze Starr.

The image of “charm city,” centered around the pleasing waterfront and blue-collar pluck, has been a notably limited narrative.

What Charm Means To Me...

“The people of Baltimore define the city's charm. Every day in my former role as health commissioner, I saw residents pull together as a community to help each other in times of need. I saw their extraordinary dedication and passion for our city. That’s why Baltimore will remain my home.”

Leana Wen | Planned Parenthood president

“The cynical may laugh,” acknowledged one local ad exec involved in the campaign at the time, “but it’s a city of charms, and we have to believe that.” Others were less charitable, suggesting that Baltimore, having lost its credentials as a working-class town, was trying to will a new identity into existence. One city promotional rep even cracked that the nickname was created “in absence of anything better.”

To add insult to injury, the campaign’s roll-out was largely seen as a total flop, with the city pushing back its release because of concurrent police and sanitation strikes, while also nixing the proposed free charm bracelets after it was determined they couldn’t afford the swag.

Baltimore magazine, among others, got in on the rebranding bashing: “Spare us!” we scoffed about the nickname in 1980, considering it nothing more than “anxious boosterism.” But little did we know then, the nickname would stick, surpassing the hyperbolic “Greatest City in America” and our personal favorite, “Come to Baltimore and Be Shocked,” courtesy of Mr. John Waters, over the course of the next four decades.

Admittedly, there always was and is still a lot to love about “Charm City”—including the desire to defend our underdog status and celebrate our undiscovered treasures. The nickname arrived at the same time, after all, that conservationists had just won a battle to save Fells Point and designate the neighborhood as our state’s first national historic district. There were plenty more rowhomes, hallowed monuments, and bold characters who could be on the verge of extinction if we didn’t give them their due.

Baltimore's iconic compact rowhomes, Formstone and all.

But all these years later, amidst seemingly ever graver concerns—spiking violence, the Baltimore Police Department disgrace, continued population decline—the moniker can’t help but feel, well, hard to live up to. The bloom is off the rose, so to speak, and even as national publications hail us as a happening city to visit, it has forced us to reckon with the nickname’s unspoken truth: that the image of “Charm City,” centered around the pleasing waterfront and blue-collar pluck, has been a notably limited narrative.

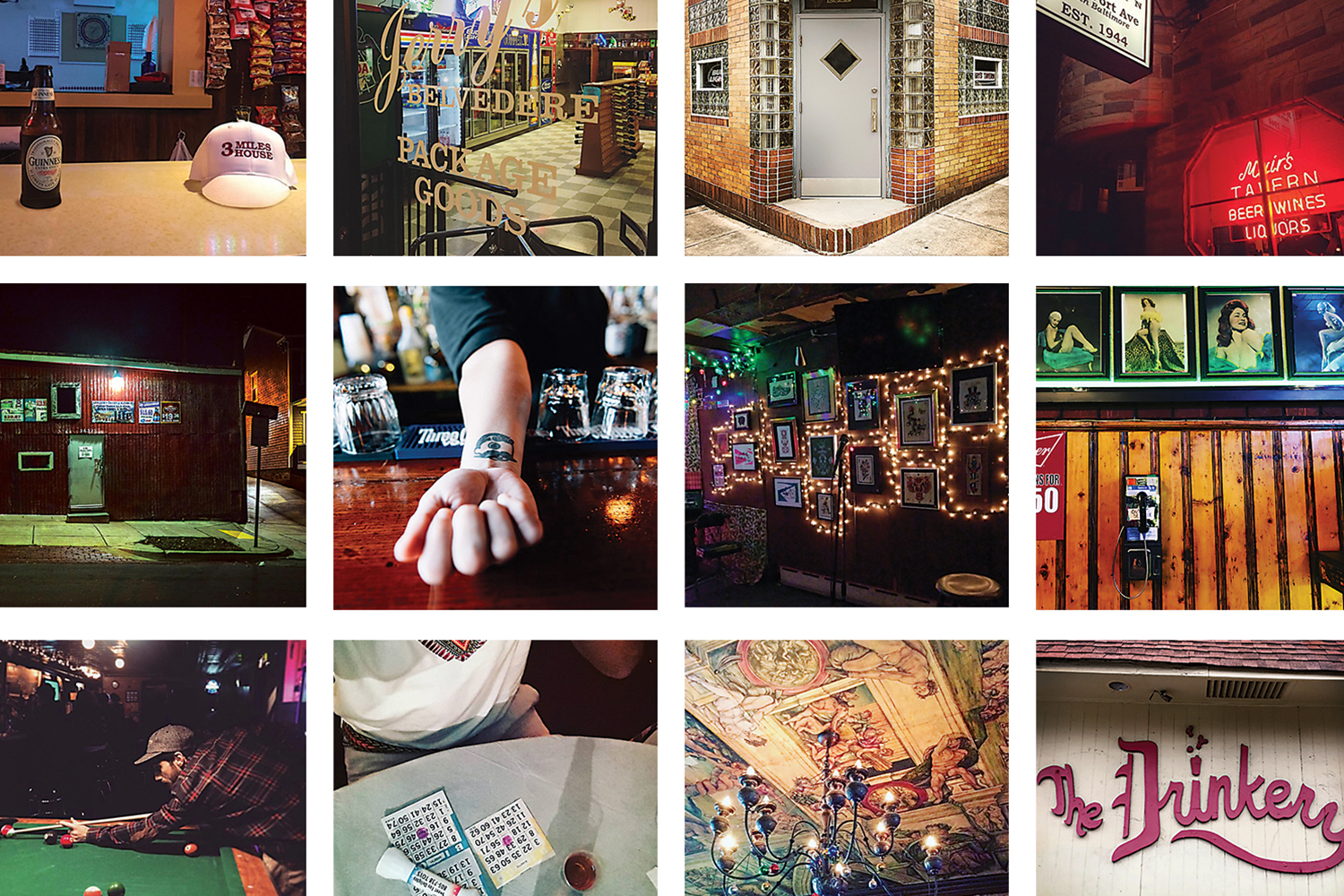

When we started to explore the concept of this cover story, we were initially interested in whether or not Baltimore had lost its charm—as the dive bars closed, as the city skyline changed, as gentrification took root in an increasing number of neighborhoods. We wondered if the failings of our great systems—infrastructure, education, law enforcement, politics—left any room for hope. But, in asking those questions, a different, thornier, perhaps more revealing question emerged: What was our charm in the first place?

What Charm Means To Me...

“I find a lot of charm in the resilience of Baltimore. There’s so much light and beauty, even in the places that look hopeless and dark, and to me, you don’t get more charming than that.”

Erricka Bridgeford

Baltimore Ceasefire co-founder

“[The ‘Charm City’ campaign] was about history, but in a particular way,” says Mary Rizzo, an American studies historian and author of a forthcoming on the city’s identity. “Part of what gave the city value was that its neighborhoods were seen as sites of community, and those communities were really defined as white ethnic communities, like Little Italy and Greektown, where Old-World neighborhoods still existed.” Ascribing special value to those neighborhoods was inherently problematic in an already majority-black town. “How do we represent a city, and who gets to tell that story?” poses Rizzo. “Charming, eccentric whiteness has become central to the official way that Baltimore represents itself.”

Even then, in the 1970s, people of color were not oblivious to the nickname’s apparent flaws: “I remember when it happened, we all looked at each other like, ‘Charm City?!’” says local artist Joyce J. Scott. “It was a glossing over.” And young people of color today have been even more forthright: “My friends and I call it ‘Bodymore Murderland,’” writes East Baltimore author Kondwani Fidel in his new book, Hummingbirds in the Trenches. “The white people call it ‘Charm City.’” Adds writer D. Watkins, “I never felt like I was a part of it. But Baltimore has always been multiple places inside one city.”

Yes, Baltimore has long been seen as a city of juxtapositions and contrasts: on one hand, the simply small-town “Charm City,” with its hons and pink flamingos, and on the other, the urban story of systemic injustices and communities trying to rise up, as depicted on The Wire. “The reality is, there are two Baltimores,” says Rizzo. “But the problem with seeing it that way ignores that they are locked together—that they affect and intersect with each other, always.”

“CHARM CAN BE A DOUBLE-EDGED sWORD. CHARM CAN BE AN ARTIFICE. AND CHARM CAN BE AN ENTRY POINT. A WONDERFUL SCREEN, WITH MANY LAYERS BEHIND IT.”

In a similar way, the more you ponder the word “charm,” the more it becomes increasingly complex—containing numerous definitions and nuances—and for that, it brings out both faithful defenders and fierce critics, just like Baltimore. “Charm can be a double-edged sword,” says Scott. “It can be like a jester, who lures you in before he lowers the boom. Charm can be an artifice. It can be a salve that covers a lot of contagion. And charm can be an entry point. A wonderful screen—something that is translucent, with many layers behind it.”

Schaefer’s 1974 slogan got many things right: our priceless architecture, our unparalleled history, our pop culture icons, and our deep-rooted traditions. We are all of those things, and yet we are so much more—611,648 disparate threads weaving together into the singular, imperfect fabric of this city. “Baltimore’s architecture is unbeatable, but not without the people who live in it,” says Kevin Brown, owner of the Station North Arts Café and Nancy by SNAC. “There are wonderful things happening here, and there are awful things happening here, too. But this is Baltimore: on any given day, it will hug you, or punch you in the gut.”

Celebrating LGBTQ pride in Mt. Vernon.

In many ways, it’s true, the city is changing, and some of its old charms will get buried in the wreckage. Something is undeniably lost as the Club Hippo closes and becomes a CVS, or Haussner’s is torn down and replaced by condos, or the relic of Recreation Pier transforms into a glitzy hotel with rooms up to $10,000 a night.

But as we move further into the 21st century, we see in the clearing many new (and old) images that would make it into our version of a city campaign: our increasingly inclusive arts scene, our new restaurants laser-focused on community, and, yes, still, the historic structures all over Baltimore that we continue to fight for. We still have the city’s crabbers that keep hoofing produce to hungry Baltimoreans; the shot-and-a-beer bars that let you linger past last call; the Formstone facades and screen paintings that stubbornly remain on rowhomes like badges of honor. There are other things, too, that are harder to capture in a photograph or catchphrase, though they are the pulse of Baltimore: enduring grit, endless gumption, a self-deprecating sense of humor, and, perhaps most importantly, our collective love for this city.

Maybe we aren’t the old Charm City we used to be. Maybe, with some hiccups along the way, we’ve become, and are still becoming, a better one. “Of course, this is a charmed city,” says Scott. “But I see charm as multifarious—a giant, amorphous, ever-changing thing. It’s really up to the people who are living in it, who are of it, to constantly redefine it.”