News & Community

Articles of War

The Maryland Historical Society’s documents, weapons, and personal items offer a glimpse of the Civil War the way Marylanders lived it.

Bull Run, Antietam, Gettysburg, Shiloh . . . on and on go the names of unforgettable Civil War battles. The seemingly endless list of destruction that spanned 1861 to 1865 left 600,000 men dead and a landscape forever scarred by the blood of brother against brother. In Maryland, a border state, the tale of division and disunion was writ large. One contemporary described Maryland during the Civil War as “the weeping maiden, bound and fettered, seeking relief.” Although officially allied with the Union, many Marylanders sympathized and supported the Confederate cause. Maryland during the Civil War is a tale of voices and loyalties split in two.

On April 15, the Maryland Historical Society’s newest exhibition, “Divided Voices: Maryland in the Civil War,” opens to the public. Unlike many exhibitions that tackle the monumental subject of the Civil War with a death march of dates and facts, MdHS has taken an interpretive path that focuses the lens on the individuals who bring the story to life. Some of the highlighted figures are familiar—Frederick Douglass, Clara Barton, Abraham Lincoln. Other individuals highlighted in the exhibition are seldom mentioned except by scholars and aficionados of the period, but their stories provide windows into what the war was like for the Marylanders who lived through it.

Through these individual stories and more than 300 objects and images from the period, some of which appear here, the war comes alive. Visitors will be struck by the depth of this collection and the endless stories these objects, documents, photographs, textiles, and weapons can still tell. The Maryland Historical Society is providing a rare experience, a most appropriate commemoration of one of the darkest chapters in our nation’s history.

—By Alexandra Deutsch, Chief Curator

DRUM OWNED BY UNION DRUMMER BOY JAMES W. SANK, 1863

DRUM OWNED BY UNION DRUMMER BOY JAMES W. SANK, 1863

This exquisitely decorated drum bears a silver plaque that reads: “Presented to James W. Sank, by the officers and men of Camp A Purnell Legion Md. Vols. May 1863.” Sank was one of many young men who were drummer boys, marching beside the ranks and often facing the most brutal fire. On the interior of the drum, a label reads, “From the Union Manufacturing Co. 98 W. Baltimore Street, Corner of Holiday, Baltimore, Maryland Drums of all sizes from $1 to $50.” Sank survived the war and returned to Baltimore to serve as a lettercarrier.

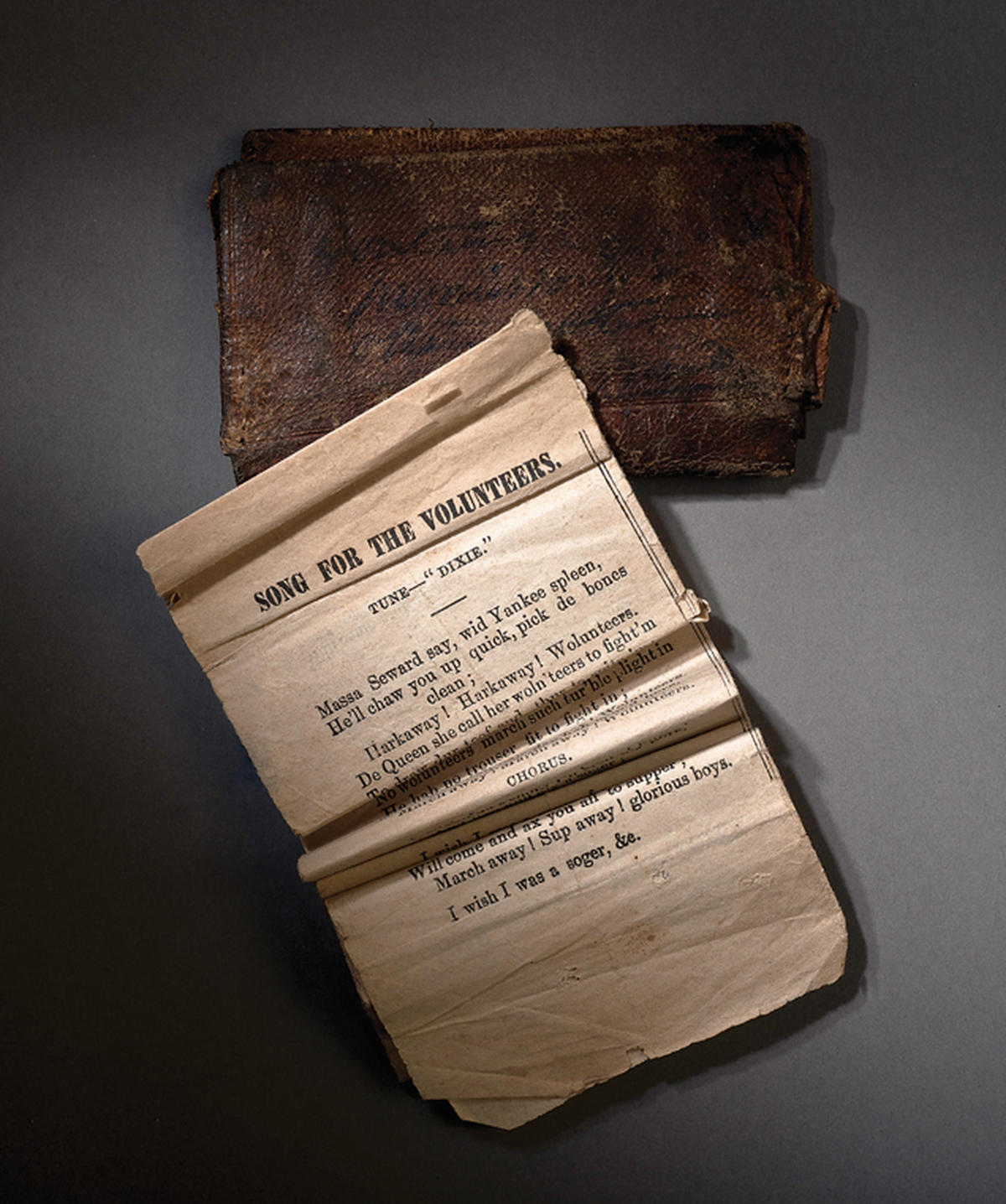

WALLET AND PAPER INSIDE WITH THE WORDS TO A “SONG FOR THE VOLUNTEERS”

WALLET AND PAPER INSIDE WITH THE WORDS TO A “SONG FOR THE VOLUNTEERS”

This small leather wallet is typical of the kind carried by Civil War soldiers, found with two period newspaper clippings inside. Sadly, the owner’s name, which was once written on it, is now illegible. The first clipping is “A Song for the Volunteers,” a song set to the tune of “Dixie” that mocks the African-American man’s desire to fight in the war, a clue that the owner was a rebel. The second clipping is a poem called “The Widow’s Offering,” a tale of a widow and her children who are left penniless after the man of the family is killed in battle.

VETERAN’S BADGE OF THE ISAAC R. TRIMBLE CAMP 1025

VETERAN’S BADGE OF THE ISAAC R. TRIMBLE CAMP 1025

This badge was owned by a member of the Isaac R. Trimble Camp, a Confederate veterans group named after one of Baltimore’s most revered rebels. Two days after the Pratt Street Riot, Mayor George William Brown asked West Point graduate Isaac Ridgeway Trimble (1802–1888), a commander of the Baltimore militia companies, to protect the city from further Northern incursions. Trimble philosophically opposed secession, but he became a fierce division commander in the Confederate Army and lost a leg at Gettysburg in 1863.

ARTILLERY JACKET WORN BY RICHARD SNOWDEN ANDREWS

ARTILLERY JACKET WORN BY RICHARD SNOWDEN ANDREWS

Andrews, a Confederate soldier, was severely wounded by a shell fragment at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862. The shell blew apart the jacket and tore open his abdominal wall. A country doctor looked at the wound and, aided only by a rusty needle, pushed Andrews’s intestines back into his body, crudely sewed up the wound, and hoped that he had made the body more presentable for the Major’s inevitable death. Miraculously, Andrews survived to be wounded again at Gettysburg and, after the war, to carry his bloodstained jacket with him when he lectured about the great conflict.

COLT REVOLVER, CARRIED BY BALTIMORE CITY POLICE, 1849

COLT REVOLVER, CARRIED BY BALTIMORE CITY POLICE, 1849

When the Pratt Street Riot broke out on April 19, 1861, cobblestones and rocks were not the only weapons used during the attacks. During this tumultuous time, the Baltimore City police under Police Marshall George P. Kane used revolvers like this one, which descended in the Reeder family of Maryland.

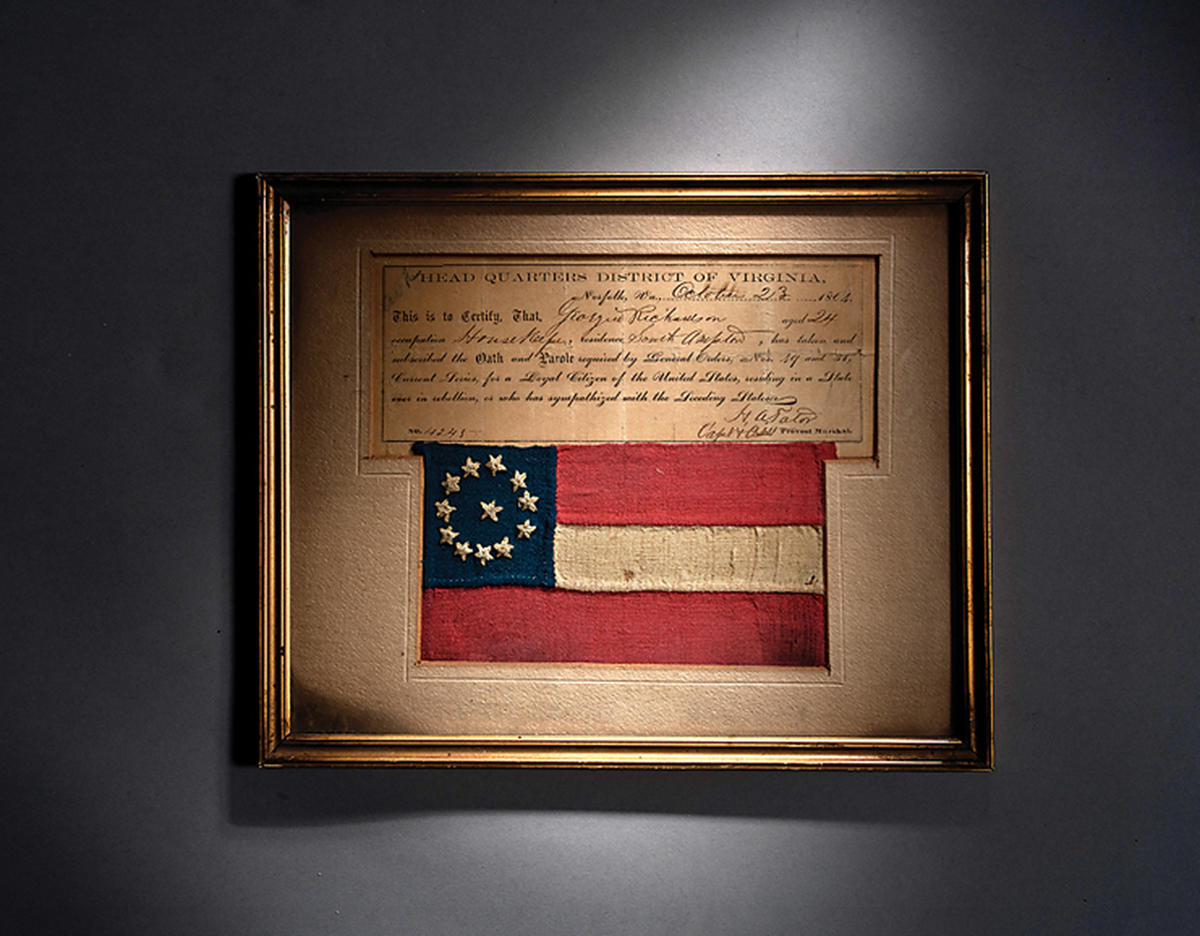

OATH OF ALLEGIANCE WITH HAND-SEWN CONFEDERATE FLAG

OATH OF ALLEGIANCE WITH HAND-SEWN CONFEDERATE FLAG

The document reads, “On November 23, 1864, Georgia Richards, a 24 year-old housekeeper in South Hampton, Virginia, took and subscribed to the Oath . . . required by General Orders 49 and 31 for loyal citizens of the United States . . .” Her pledge to the Union was framed with a Confederate flag, demonstrating that she took the oath only to avoid imprisonment.

GENERAL LEE’S CAMP CHAIR

GENERAL LEE’S CAMP CHAIR

A plaque on the worn, repaired seat of this simple Victorian folding chair reads: “Camp Chair Of Robert E. Lee Used At The Field Headquarters Second Battle Of Manassas War Between The States.” As the battle now known as the Second Manassas erupted, General Lee’s beloved but ornery horse, Traveler, threw him. The General suffered two sprained wrists and retreated to his tent as the battle ebbed and flowed nearby, likely finding comfort in this chair. Baltimorean Joshua Thomas, the chair’s donor, is said to have served as one of Lee’s clerks during the war.

GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC HAT

GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC HAT

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a national veterans’ organization formed immediately after the Civil War. It was limited to Union veterans, and camps were established throughout the country. In 1867, Commander-in-Chief of the GAR, General John A. Logan, established May 30 as Decoration Day, later known as Memorial Day. It was originally intended to commemorate the Union dead of the Civil War by decorating their graves with flowers and flags. Veterans held an annual “National Encampment” every year from 1866 to 1949.

BULL’S-EYE CANTEEN

BULL’S-EYE CANTEEN

Originally, this Civil War canteen would have been covered with wool. Few examples survive with their original fabric coverings. After the war, Philip Eckel Layman, who served in Company A of the 5th Maryland Infantry Regiment, decorated this souvenir with the American flag. Layman fought for the Union from 1861-1865 and served time in Libby Prison, the infamous Confederate facility in Richmond, VA. His grandson donated the canteen to the Maryland Historical Society in 1992.

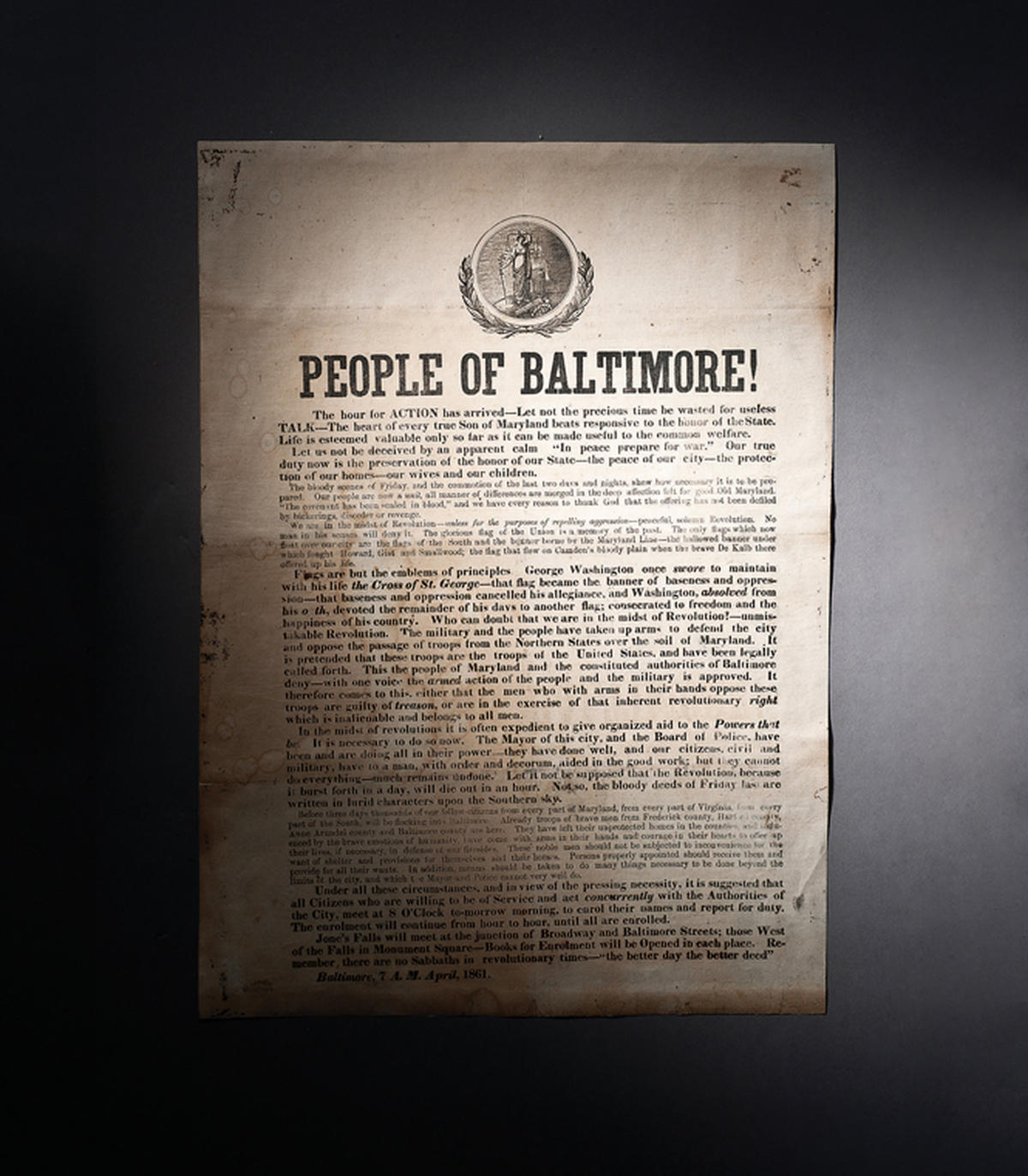

PEOPLE OF BALTIMORE! APRIL 21, 1861 BROADSIDE

PEOPLE OF BALTIMORE! APRIL 21, 1861 BROADSIDE

Tacked to buildings and hung in windows, broadsides spread word quickly and effectively. This one was printed two days after the pivotal Pratt Street Riot during which pro-secessionist and Southern-sympathizing citizens of Baltimore attacked the 6th Massachusetts regiment traveling through Baltimore under Lincoln’s orders. The city was on edge awaiting the next act of violence. This broadside urged the citizens of Baltimore to join up to defend their city and their homes and encouraged them to support the troops pouring into Baltimore to defend the city from Northern abuses.

HAND-CARVED WOODEN ROSARY CARVED BY CONFEDERATE PRISONERS

HAND-CARVED WOODEN ROSARY CARVED BY CONFEDERATE PRISONERS

Today, the picturesque peninsula known as Point Lookout is a Maryland state park known for its natural beauty and recreational opportunities. Its peaceful surroundings belie its history as the location of one of the worst Union prison camps during the war. As many as 52,264 Confederate soldiers, some of them Marylanders, were imprisoned there and endured its wretched conditions. Soldiers found ways to wile away the time during their imprisonment, carving trinkets for loved ones. This rosary was probably made for family and friends who were waiting for the prisoners to come home.

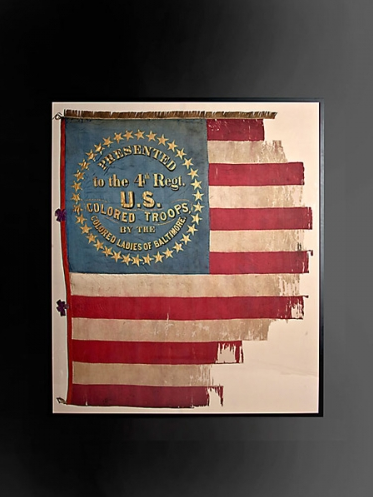

4TH U.S.C.T. NATIONAL FLAG MADE BY THE “COLORED LADIES OF BALTIMORE” CARRIED IN THE BATTLE OF NEW MARKET HEIGHTS IN 1864

Baltimore-born, college-educated Christian Fleetwood had just turned 23 when he enlisted in the 4th Regiment, United States Colored Troops. Led by white commissioned officers, Fleetwood’s education and intelligence propelled him to sergeant major, the highest enlisted rank an African-American could attain.

In the early fall of 1864, Fleetwood’s regiment was part of an assault on heavily defended New Market Heights outside of Richmond, Virginia. After two color guards went down in a hailstorm of fire, Fleetwood seized this flag and rushed into the fray. In retrospect, Fleetwood thought he survived the brutal engagement because he was such a “little fellow” and the bullets went over his head.

Although small in stature, Fleetwood was so admired for his bravery that he was presented with a Medal of Honor, the lasting recognition of his contribution to the war. In 1865, all of the regiment’s white officers petitioned Secretary of War Stanton to promote Fleetwood to the rank of commissioned officer. Although Stanton denied the request, Fleetwood remained committed to his country and continued to serve in military affairs in Washington, D.C. until his death in 1914.

CARVED FIGURE OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN

Little is known about this folk art figure of Lincoln, but it was carved in Somerset County, Maryland just after the war. It is a testament to the lasting memory of the man still revered as one of America’s greatest presidents. The presence of the beard rules out the possibility that it was made when Lincoln ran in the election of 1860. At that time, he was beardless.

CONFEDERATE NAVAL OFFICER’S FROCK COAT WORN BY ADMIRAL FRANKLIN BUCHANAN

Confederate naval officers’ frock coats are rare. This one conforms perfectly to the regulations established by the Confederate naval authorities.

Immediately after the 1861 Pratt Street Riots, career naval officer Franklin Buchanan resigned his post as First Superintendent of the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis and accepted Jefferson Davis’s offer to command the Confederate Navy. In 1862 as commander of the ironclad Virginia, Buchanan attacked and sank the Congress, the Union blockade vessel on which his brother, McKean Buchanan, was Paymaster. Buchanan’s is a story of “brother against brother” on the sea. He was wounded in the fight, missing the Virginia’s momentous fight with the Monitor the very next day.

ROBERT E. LEE’S GENERAL ORDER NO. 9

Upon Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender to the Union Army at Appomattox Court House (a village in 1865) Lee made his farewell address to his men. Lee’s general order to cease fighting and return home is poignant in its simplicity and gratitude for the efforts of those who fought and sacrificed for the cause of the South and for himself. Transcribed by a clerk at the Headquarters of the Army of Northern Virginia, twelve original copies were made to be sent to Lee’s regiments, with an additional copy given to the clerk. Immediately the order began being duplicated with versions disseminating across the country. This is one of those copies, Some of these, such as the Order No. 9 held by the Maryland Historical Society, are signed by Lee himself.

WALLPAPER FROM PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S BOX AT FORD THEATER

Few events in American history are as notorious as John Wilkes Booth’s successful plot to kill President Abraham Lincoln. The actor-turned-murderer hailed from Maryland, a fact sometimes overlooked when recalling his crime. The dramatic manhunt that took place in the wake of that evening at Ford’s Theater tracked Booth through the state and into Virginia where he was killed on April 26, 1865.

This wallpaper, removed from the private box at Ford’s Theater in which President Lincoln was sitting when he was shot, is part of the Mary Ann Booth Papers held by the Maryland Historical Society Library. The collection, on permanent deposit, pulls together several pieces of memorabilia relating to this Maryland family, including letters from Mary Ann Booth to her son John Wilkes Booth and notes. Despite dying a murderer, Booth remained beloved in the minds of his mother and particularly his sister, Asia. This scrap of wallpaper attests to their lingering obsession with a family member who became one of American history’s most despised men.

ADALBERT VOLCK, “SEARCHING FOR ARMS,” MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY H. FURLONG BALDWIN LIBRARY COLLECTION, PP247

Following the Pratt Street Riot of April 19, 1861, the need to preserve Maryland’s allegiance to the Union became even more evident to President Lincoln. The secessionist sentiments that inspired the riot made the divisions within Maryland profoundly evident. President Lincoln took action to keep Maryland in the Union, rescinding the writ of habeas corpus, one of the legal safeguards against unjustified imprisonment. In addition, he placed Maryland under martial law. Soon Federal troops were stationed on Baltimore’s Federal Hill and cannons were aimed at the Washington Monument in the city’s Mount Vernon Square. Individuals under any suspicion of loyalty to the Confederate cause were arrested and placed in Fort McHenry and other northern prisons. Houses were searched for Confederate materials, weapons, and any other evidence of actions against the Union.

In this cartoon, Volck depicts a nighttime “raid” by Federal troops on a Baltimore residence. The women of the house huddle together in their shifts while an older gentleman is menaced by two Union soldiers. Two Confederate flags, the famous “stars and bars” are found, revealing the family’s true loyalties. These “unlawful” searches, seizures, and imprisonments outraged citizens such as Volck, whose defiance of the Union cause was further strengthened by this type of event.

ADALBERT VOLCK, “PASSAGE THROUGH BALTIMORE,” MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY H. FURLONG BALDWIN LIBRARY COLLECTION, PP247

Adalbert Volck (1828–1912) was a Bavarian-born dentist and satirical caricaturist whose political cartoons lampooned President Abraham Lincoln and the actions of the North against the South during the Civil War. A staunch, almost militant supporter of the Confederacy, Volck used the pseudonym “V. Blada” and is said to have been a smuggler for the Confederacy as well as a courier for Jefferson Davis, the President of the Confederate States of America. This image depicts the newly-elected president skulking through Baltimore on his way from Springfield to Washington, afraid of a rumored mob attack on his train. Lincoln’s election had resulted in Democrats assaulting Republicans in the city’s streets.