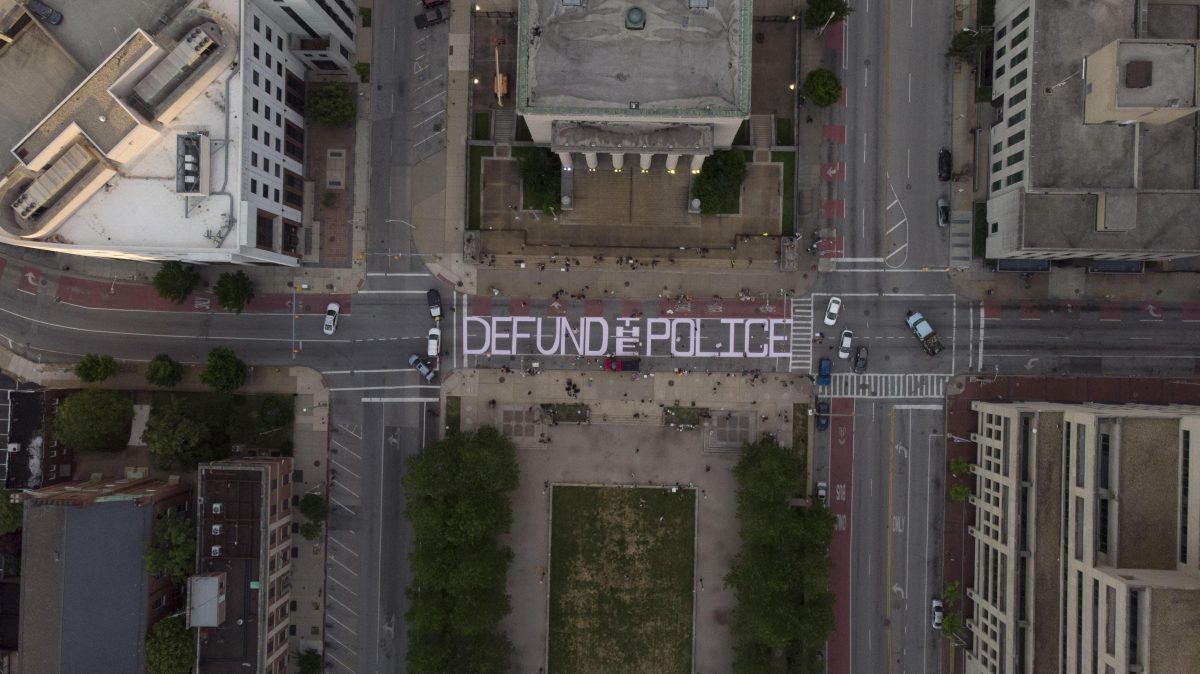

Two-hundred-plus demonstrators calling for cuts to the Baltimore Police Department (BPD) budget, and a reallocation of BPD funding to other agencies, marched to City Hall Friday afternoon with several protestors painting “Defund the Police” in large, block lettering on Gay Street.

Protest organizers, including local grassroots group Organizing Black, said they set the time and place of the rally to send a message to the City Council as they began their virtual budget hearings Friday afternoon. Among those attending the budget hearing was Police Commissioner Michael Harrison, along with other officials.

“The police budget increases every year, and every year, there’s more crime,” Taz Gaines, with Organizing Black, told reporters as the street painting got underway. “Why are we still increasing funding? We should be taking away funding and adding it to education and housing. It’s not just about defunding the police, but reinvesting that money back into the city.”

Marchers met at Baltimore’s Central Booking and Intake Center at 3 p.m. Friday before walking the roughly 10 blocks to City Hall, where they met other demonstrators. Other groups partnering in the rally included Baltimore Bloc and CASA.

Throughout the past 30 years, the BPD’s budget has tripled while Baltimore City Recreation & Parks funding has remained nearly flat.

According to a 2017 Fiscal Year study by the Center for Popular Democracy, which was published by Forbes last week, Baltimore has the highest level of per resident policing, by far, of any large city in the country.

With a city operating budget of $2.6 billion that year, $480.7 million was dedicated to policing in Baltimore. That represented 18.2 percent of Baltimore’s total operating budget, which equates to $772—the highest level in the report by far—per person on policing, a figure more than double that of Los Angeles, for example.

Recent Morgan State University graduates Chrissy Okemkpa and Taylor Boykin attended the rally in front of City Hall. Both said it was important for them to be present given the recent protests against police brutality in the wake of the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, as well as the subsequent calls to shift police funding to other functions that benefit the community—which they believe is needed.

“It’s not enough for people to just be on social media and say they support something,” Okemkpa said. “We wanted to be here. We wanted be present. That’s how you show you support the movement and calls for reform and changes.”

She continued: “We went to school in the city. We’re both from Baltimore, and the city spends too much money on policing—we see it. There’s a lot of inequities that need to be addressed—public health, food desserts—and yes, police brutality.”

Boykin also highlighted the need to shift the police department spending elsewhere.

“Education definitely needs more money,” said Boykin, who mentioned a need for more recreation centers and after-school, weekend, and summer opportunities for city students.

Michaela Brown, one of the Organizing Black leaders, said the group is demanding that 50 percent of the police department’s budget be redirected to infrastructure, education, housing, health care, and social services.

She also said they were calling for the repeal of Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights (LEOBOR), which can hinder investigations into allegations of police violence. Police supervisors, for example, may not question their officers for 10 days following an incident report.

City Council members met virtually last week to review the $3 billion operating budget put forth by Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young for the next fiscal year, which is scheduled for a vote on Monday. Young’s proposal would give the Baltimore Police Department a budget of $550 million, which is roughly 20 percent of the entire city budget and an increase of around $21 million.

Council members can negotiate funding priorities with Young and his administration, but they only make cuts to the proposal and cannot increase spending in any one area.

A perennial problem with the police budget is the roughly $40-$50 million that is spent each year on overtime. Police Commissioner Harrison said he is determined to do better, and he demonstrated that by decreasing overtime costs by about $5 million in the last year. He also eliminated vacant positions and generated savings through reduced legal settlements.

More cuts, Harrison warned, will “have very serious consequences,” such as longer response times and more unsolved crimes.

Even before recent protests, Young described the fiscal 2021 budget process, which goes into effect in July, as “incredibly difficult,” given projected revenue decreases because of the COVID-19-related economic shutdown.

“Every City and county in the country are facing difficult budgetary decisions, and Baltimore is no different,” Young said last month when he released his budget outline. “What sets us apart, however, is the fact that even in the face of financial pressures, our commitment to our children and families is rock solid. The budget I presented makes very clear that Baltimore values its children, older adults, and most vulnerable residents.”

Earlier Friday morning, hours prior to the march and rally at City Hall, other protesters met outside the South Baltimore rowhouse of City Councilman Eric Costello, the chairman of the council’s budget and appropriations committee, calling for him to cut police spending and redirect the funding to other urgent needs. Costello responded by phoning—and apparently expressing anger toward—a local parent of one of the photojournalists covering the protest.

Costello later issued an issued an apology for his actions.