News & Community

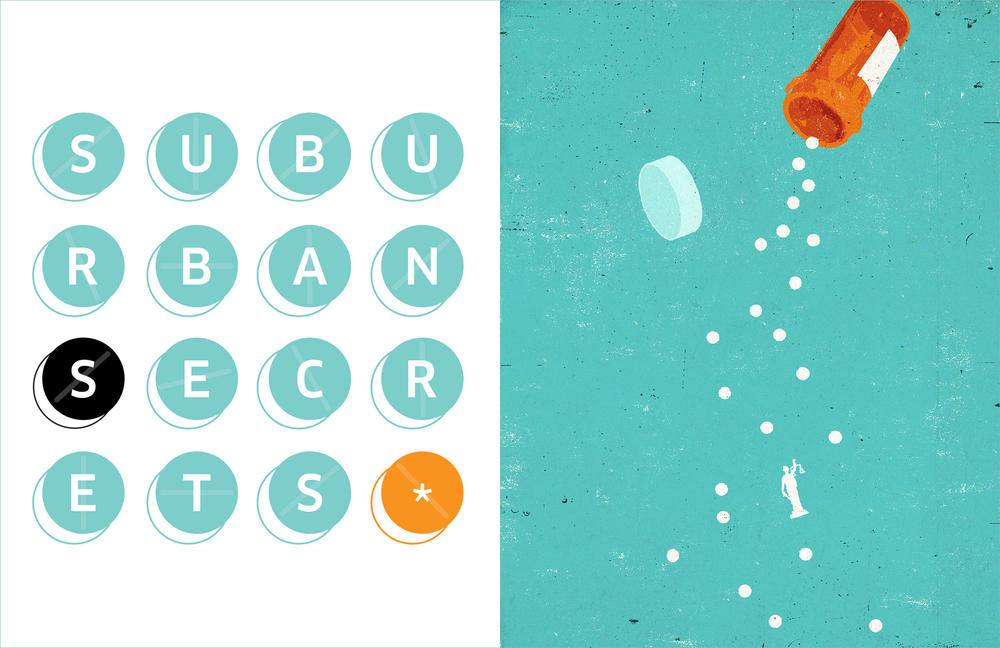

Suburban Secrets

A Baltimore County mother and lawyer gets charged with oxycodone distribution and smuggling prescription drugs into jail. Only police and addiction specialists don’t seem surprised.

At 7:43 a.m., on a clear, otherwise picture-perfect morning, the first day of October, Baltimore County Vice Narcotics and Gang Enforcement Team officers—in full tactical gear with weapons drawn—begin yelling and pounding on the front door of a four-bedroom, two-and-a-half bath, two-and-a-quarter acre brick home on Manor Road in Phoenix. If they’re not up already, families in this bucolic neighborhood will be soon, trying to get their kids off to school. One next-door neighbor comes outside, concerned that there’s been some sort of medical emergency.

“Police with a search warrant!” the officers bellow. “Open the door! Police with a search warrant! Open the door!”

The home’s windows are open—it had been that kind of breezy, autumn sleeping weather the night before—but there’s no response from inside the house. And now the police, having announced their presence, break through the door with a battering ram. Just inside, standing in the living room near one of the two sofas, officers immediately identify 50-year-old commercial insurance broker Francis “Chip” Carnes. But initially, they are unable to locate the target of their search warrant—Carnes’s fiancée, attorney Jill Swerdlin—though they do locate her 8-year-old son in an upstairs bedroom.

Eventually, police discover Swerdlin in the basement of the $370,000 home, near a washbasin—there’s a Ziploc-type baggie with white residue atop the sink’s drain. Handcuffed and brought upstairs, Swerdlin, still in a long nightshirt, is told to sit in the living room across from Carnes, also in handcuffs, where both are read their rights per Miranda. That’s when Det. Douglas Kriete, a thickly built, goateed, ponytailed, 31-year police veteran, asks the couple if there is anything illegal in the house. Carnes, again, not the target named in the warrant, tells Kriete that there may be “some old smoking devices”—the words from the police report—meaning crack pipes, in the bedroom. Swerdlin concurs, according to the same police report, adding that there are guns in the basement inside a safe near where she was found by police.

None of this, however, is why the police are here.

A self-described “Jewish mother of two kids” from a prominent Baltimore County family of attorneys, Swerdlin, 47, was the focus of a five-month investigation and grand jury indictment, with prosecutors alleging that she was the center of a “hub and spoke” conspiracy to distribute illegal prescription drugs. The indictment alleges Swerdlin, a former public defender in private criminal defense practice for the past five years, provided legal services in exchange for illegal prescription drugs; possessed and distributed controlled substances, including oxycodone; conspired to distribute illegal prescription drugs; and—this was the kicker that sparked media attention when she was arrested—smuggled illegal prescription drugs into the Baltimore County Detention Center.

But while being questioned, Swerdlin initially refuses to talk about her role in obtaining or exchanging illegal prescription drugs, according to police. Only when Kriete threatens to end the interview and simply take her away, he testifies later, does Swerdlin open up to his more obliging, younger partner—the “good cop/bad cop” routine. Once her son has been fed breakfast and walked to the bus stop at the end of driveway, Swerdlin, who would certainly be expected to understand what’s she’s agreeing to do, appears to come clean.

This is what she wrote:

“In 2009 I was in a serious car accident and due to my injuries I was prescribed oxycodone. After approximately a year my dr. discontinued my prescription. I was still in pain and addicted to oxycodone so I purchased them from people who were selling them for money. I have given other people pills who needed them and I have asked other people close to me to get them for me. I am ashamed about my behavior especially because I am an officer of the court and have been a professional for 23 years.”

Then, potentially damaging, in terms of legal consequences—Swerdlin also participates in a written Q & A. In response to detectives’ questioning, she affirms, among other things, that she involved her 28-year-old legal assistant (charged with possession and intent to distribute) in oxycodone exchanges and that she brought, on one occasion, illegal prescription drugs to a client jailed at the Baltimore County Detention Center to increase her fee. She gives up the names of 11 people from whom she received oxycodone pills, including former clients with violent histories. And when detectives also ask if she provided oxycodone to her 20-year-old son Brett, who has pled guilty to one count of possession of a controlled and dangerous substance in an arrest related to the investigation, she writes, “Yes.”

TOWSON-BASED CRIMINAL DEFENSE ATTORNEY JILL SWERDLIN AFTER HER ARREST ON PRESCRIPTION DRUG DISTRIBUTION CHARGES

That would seem like case closed. Police take “green dot,” pre-paid debit cards from the house, confiscate a cellphone, planner, and receipt book as evidence—as well as a couple of pills, more baggies, vials, and paraphernalia. End of the story; except it’s not. Seven months later, in a Baltimore County Circuit Court criminal motions hearing this past May 16, Swerdlin—tall, slim, in a conservative black dress, sweater, and heels—claims her civil rights were violated by officers and that a quid pro quo offer was made by detectives.

Fidgeting, shooting glances back at Carnes (who was eventually charged with possession of cocaine and paraphernalia) from the defense table—and told at one point to “sit still” by Judge Timothy L. Martin—an understandably anxious Swerdlin and her attorney argue that her statement, particularly that less sympathetic Q & A, should be thrown out. In the meantime, the Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland has sought an injunction to stop Swerdlin from practicing, alleging professional misconduct in a civil suit, including misleading clients about her ability to influence judges, and accepting money for legal services and then failing to provide those services. Swerdlin and Carnes also face a forfeiture suit regarding the shotguns (essentially Carnes’s hunting rifles) located in the Manor Road house because of the proximity to alleged illegal narcotics.

Then there are other personal things to contend with: Her Pikesville townhouse is in foreclosure; there are contract and tort claims being brought against her by two former clients; plus, family issues—her son Brett is living in a North Carolina recovery house, while his father, her first ex-husband, has stopped talking to her. Swerdlin, who agreed to be interviewed for this story even as she faces a plea hearing in mid-June, says she’s been clean and sober ever since her arrest and subsequent treatment, but it’s a lot for anyone deal with, let alone someone trying to recover from drug addiction.

But there’s still the broader question. How exactly does all this suddenly happen to a former St. Paul’s School mom with no previous criminal record? Why, for example, do Baltimore County police and addiction specialists say they aren’t surprised anymore that an upscale lawyer, following a doctor’s prescription for pain medication (at least initially), finds herself hustling pills from convicted drug dealers? Just how bad is the prescription painkiller problem in the suburbs?

If the stereotype persists that somehow this country’s drug problem is an inner city, “urban” crisis—read: low-income, poorly educated blacks or Latinos using crack cocaine or heroin—it’s time to put an end to that notion. And if the belief persists that soaring prescription opiate abuse in the U.S. is somehow relegated to Appalachia or some other poverty-stricken region where unemployed white people live—it’s time to put that notion to bed, too.

One good way to get a handle on the extent of the prescription drug problem is to look at the hard data on accidental overdoses.

In 2010, prescription drugs killed more than 22,100 people in the U.S.—triple the number from a decade ago, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)—and more than twice that of cocaine and heroin combined. What’s more, opiate pill addiction is now being blamed for reversing an earlier decline in heroin-related overdoses. Two years ago, the Maryland Department of Health reported that heroin-related overdoses had begun to spike again, and they linked the uptick to prescription opiate use that eventually becomes heroin use when the addict can no longer find or afford prescription opiates.

Most dramatically, recent studies show that for the first-time, more deaths are attributed to drug overdoses than car accidents or gun violence. But still think someone from Swerdlin’s demographic is an atypical drug addict or that it’s largely a teenage problem? According to the CDC, prescription drug overdose rates are highest, by far, among whites when compared to African-Americans or Latinos, and also highest among those aged 35-54—with both rates continuing to climb. Prescription overdose death rates among women, in particular, have reached unprecedented levels, increasing 400 percent from 1999 to 2010.

“This cuts across all boundaries, all levels of society,” says Mike Gimbel, Baltimore County’s former “drug czar” for 25 years. “And it is a huge problem in the private schools. But when teenagers start experimenting with pills today, they usually begin in their parents’ bathroom cabinet.”

And yet all of this is still a fairly recent development. It wasn’t that long ago, in 2006, that the Baltimore County Police Department first deemed it necessary to create a new narcotics unit, the pharmaceutical drug diversion team, specifically to tackle the crisis of the illegal distribution of prescription pills. That first unit only had two officers. Today, the unit is managed by a corporal and a sergeant, who oversee five detectives. In 2013, the unit made 305 arrests, including 168 for felonies, many including violent offenses, and they executed 52 search-and-seizure warrants like the one that brought them to Manor Road—far surpassing the numbers for any other illegal drugs.

Baltimore County police sergeant Bruce Vaughn notes this was all accomplished despite the unit’s having to overcome greater obstacles than other narcotic units, because they’re going after a black market for drugs that are legal when prescribed correctly. Also, HIPAA privacy laws can bog down background investigative work. “These can be complicated cases,” Sgt. Vaughn says. “Like investigating financial crimes.”

According to law enforcement, prescription drugs have become a driver of criminal activity because so much money is involved. The going rate is now $30 for a single 30 mg pill, compared to, say, $10 for a small amount of heroin—and that, for all intents and purposes, prescription drugs have become street drugs. They’re often trafficked by the same people who sell heroin, coke, and marijuana, often violent offenders. The former client Swerdlin allegedly smuggled drugs to inside prison is there on armed robbery charges. He has also been charged with attempted murder in the past. In fact, a number of those initially charged in the indictment with Swerdlin have been found guilty of distributing other drugs previously. Four are former clients and a couple have faced armed robbery and firearm charges.

“We could use five more detectives,” Kriete says. “The prescription drugs take up more than triple [the time] of anything else we deal with.”

Gimbel, himself a longtime recovering heroin addict from Pikesville, calls prescription painkiller drugs like OxyContin “heroin in a bottle” and says that 80 percent of the calls he receives today from families seeking help for a loved one are related to prescription drug abuse. “It used to be 5 percent.” He says anyone taking these powerful pain medications every day for 30 days will begin to build a tolerance—inevitably suffer withdrawal symptoms—and that it should be protocol for every patient to go through a medically supervised detoxification program. “Look, this stuff isn’t coming from Central America, Columbia, Peru, or Southeast Asia,” Gimbel continues. “It’s doctors that are prescribing this stuff.”

Once addicted, he and other recovering addicts say, all bets are off.

“You cross every line that you think you’ll never cross,” says Linda Y., a former Johns Hopkins nurse who was fired for shooting up pain medication intended for patients in the bathroom at work. (She asked to remain anonymous in accordance with 12-step tradition.) The assumption is that a lawyer or nurse, or any suburban professional for that matter, lives two lives once they become an addict, but that’s not true, Linda says. “It’s one life,” she says. “It all revolves around getting what you need.”

She adds that the problem of prescription drug abuse is particularly acute in the world of health care providers given the access that doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and others have to medication—and notes that 12-step meetings in the Roland Park, Rodgers Forge, and Homewood areas are frequented by individuals in those industries. Linda went through a three-year, Maryland Board of Nursing discipline and rehabilitation program, including treatment and drug screens, to earn back full practicing credentials, adding, “I wish it had been five years like it is today. I needed it. It really helped me.”

Bob D., a 49-year-old lawyer who went through treatment for prescription drug addiction at Father Martin’s Ashley’s two-year pain recovery program in Havre de Grace, was initially prescribed medication for a rare neurological condition. But ultimately, the “cure” for his pain became worse than the underlying problem. He hid his addiction as long as possible, “doctor shopping” (going from one doctor to the next, hoping each would authorize a new prescription) and keeping the true number of pills he was taking from his neurologist and partner. “I was obsessed with my ’scripts,” he says. “I started with a pill every day like I was picking up my morning coffee. It was three or four years of a living hell.”

In fact, one of the things Bob says he learned at Father Martin’s Ashley was that drugs used to treat chronic pain, like oxycodone and hydrocodone, are not only addictive and potentially deadly—“my greatest fear was that I would forget how many I took and not wake up one morning”—but often don’t work long-term for chronic conditions. And these drugs can actually create a change in the neurological system where people develop hyperalgesia and become far more sensitive to pain than when they started out on these drugs. Today, Bob follows a routine he began at Father Martin’s Ashley that includes A.A. meetings, meditation, prayer, deep-stretching exercises, and some yoga to treat both his addiction and chronic pain. He reports he’s begun playing tennis again for the first time in years.

Ground up and snorted, or injected, which some abusers do, prescription pain pills can mimic the high of heroin, but even in pill form, opiates can create a false sense of euphoria and well-being, which is part of their insidious nature, says Dr. Carol Bowman, a Father Martin’s Ashley addiction specialist. “An injury sends a message to the brain. The medication, however, blocks the neuroreceptors and sends those signals away—but it also blocks all pain signals,” Bowman says. “It doesn’t distinguish if it’s anxiety, depression, or physical pain.” She adds that it doesn’t take long, either, for the drugs to confuse the brain’s normal “feel-good” chemical processes. “When they stop being taken, they suppress the brain’s natural production of dopamaine, our natural reward system, which also begins another downward spiral.”

Gimbel—who says he’s seen weekend warriors with knee and back injuries get hooked—believes there’s also a deeper societal component underlying the problem. “Everyone who gets admitted to the hospital today is asked to assess themselves for pain on a scale of zero to 10—that wasn’t always the case,” he says. “The target is always zero with the pharmaceutical companies pushing their products, so doctors try to get everyone down to zero. It’s like no one is supposed to experience pain anymore. It’s, ‘Here take a pill.’”

“And of course, all of this is just treating the symptoms,” Bowman adds, “not the actual causes of the original pain, which is what we should be examining.”

It’s this dual track—the physiological and psychological—that makes addiction, and treating addiction, tricky to fully understand, says Dr. Michael Fingerhood, director of the division of Chemical Dependency at Bayview Medical Center. There is a genetic component to addiction that makes some people more susceptible; there is a “phenomenological” component (i.e., stressful events or periods); and there’s the purely physiological aspect (the physical cravings)—particularly with the powerful round of painkiller drugs that were introduced en masse a little more than a decade ago.

“These are not your mother’s Valium or a drink after work: ‘Tough day, I think I’ll have a Percocet.’ But people think they are because they’re prescribed,” Fingerhood says. “I’m not surprised at all that people get to a place where they don’t know who they are anymore and can’t ask for help. Prescription drug addiction is the elephant in the room. It’s the epidemic no one talks about.”

A few days after her mid-May criminal motions hearing, outside a bustling Panera Bread cafe in the Hunt Valley Towne Centre shopping complex, Swerdlin—calmer than she appeared in court, dressed in a sleeveless white blouse, her hair colored a darker hue than in her smiling mug shot—recalls the car accident that ultimately led to her addiction, and to her journey from defense attorney to defendant. She’ll never forget the date; it was her 44th birthday, Jan. 6, 2009.

“I was leaving the Baltimore County courthouse, headed for Wabash Avenue, and it was raining. I was going about 5 mph on Allegheny [Avenue], trying to see, my view was obstructed, and I got T-boned,” she says. “My BMW was totaled, and I was taken to the hospital.” Police reports aren’t clear about who was at fault, but Swerdlin says the young driver of the other car was speeding. Her car did a 180-degree spin, and though she was wearing her seat belt, her face smashed against the empty passenger seat, badly damaging an eye socket and fracturing her cheek. “Of course, when I left the hospital,” she says, “I had the prescription for oxycodone.”

Her doctor cut off her prescription approximately a year later. But she says she needed oral surgery, which led to another prescription. She also says that she hit up friends and family members from time to time for pills, telling them that she didn’t feel well for one reason or another. “I didn’t go the doctor route [doctor shopping] and didn’t want to go through insurance,” she says, adding that she was “professionally, ethically, morally too proud” to have that on her medical records. Instead, she says, she found it easier to get what she needed from clients she was representing, who had been accused of drug dealing.

“Being a criminal defense attorney made it accessible,” Swerdlin says. “I started taking on clients who were drug clients. I started getting a good reputation from defending drug dealers, trying to get them into drug rehab and drug court, and I got to where I was making good money dealing with high-level people.”

She was eventually taking “five to seven” pills a day, starting first thing in the morning, then spread throughout the day, and “not eating lunch for years” while she hurried to track down pills, argue her cases, and make it to school to pick up her youngest son.

She also says that her addiction was “at low level for a long time, probably until six months to a year” before her arrest and “then it went from zero to 60 in a hurry.” She says that she was able to keep her use and behavior a secret from those closest to her, and that Carnes “had no idea” why the police broke into the house last fall.

Court records, police testimony, and allegations from other clients suggest life began getting unmanageable for Swerdlin before last fall, however. For starters, it was not long after her accident in 2009 that her name began to regularly appear as a defendant. Initially, it was for minor things. In 2010, there was a contempt charge that was dropped. Then there were a number of traffic violations, starting in 2011—driving with an expired tag, failing to produce a vehicle registration card, and later driving with a suspended license and other charges. Also, in 2011, her condo association sued for late fees. There’s the foreclosure that begins in 2011. And, Baltimore County police say she popped up on their “radar” in January 2012—a year before she says her addiction become serious—as part of a separate and still ongoing investigation (although Swerdlin is not accused of running any sort of major drug ring).

The first claims of professional misconduct, including that she took money in return for legal services not provided, date back to the fall of 2012. But most of the seven allegations, all of which Swerdlin denies, occurred more recently, in 2013. Baltimore County assistant state’s attorney Jason League, who is prosecuting the Swerdlin case, notes that she continued to represent drug clients even after her arrest until the Attorney Grievance Commission of Maryland filed an injunction.

Her testimony at her criminal motions hearing also differed substantially from that of the four police officers called to the witness stand. She testified that she believed her house was being robbed and under attack, possibly from a disgruntled former client, when police pounded on her door. She says she heard, “Get down, this is a robbery,” not “Police with a search warrant! Open the door!” She also says that she was in the basement near the washbasin when found by police because she was trying to run from the house to get help. Taken with her allegation that male officers helped her get dressed—and not the female officer who was called to the scene—and claims that a quid pro quo was offered (that police told her they would not arrest her fiancé and she’d receive a better deal if she agreed to the Q & A), Judge Martin said in court that he did not find her testimony “terribly credible.”

Of course, disputes in court over the facts aren’t uncommon. At the same time, Swerdlin seems to be walking what could look like a fine line to a jury at the moment: admitting to addiction and obtaining and using illegal prescription drugs while declaring herself not guilty of the most serious crimes of which she is accused.

“I’m an addict,” Swerdlin says. “But I’m not guilty with what they are charging me.”

She also says in the interview at Panera Bread that the Baltimore County police only found a single piece of paraphernalia, a spoon owned by her 20-year-old son, in the search of her and Carnes’s home. (Reached by phone, her son would not comment.) But, according to police reports, four burnt pipes were found, and it was Carnes who was charged with possession, not her oldest son—who lived in her Pikesville townhome at the time. Nonetheless, she suggests that charges against Carnes will be dismissed if she accepts a plea.

As far as the allegations that she took payments in return for legal services not provided—in one case a judge has already ruled in favor of the plaintiff—or other accusations that she implied that she could influence judges, Swerdlin says, “Once people found out what happened to me,” referring to her arrest, “they started coming out of the woodwork, looking for money.”

And finally, she also claims she is being unfairly targeted by law enforcement officials because of her “elevated status” as an attorney. “I’m not being treated like everyone else,” she says. “The state is trying to make an example of me.”

Meanwhile, even as Swerdlin maintains she’s being unfairly treated by law enforcement and prosecutors, she weaves 12-step lingo into the conversation, speaking about taking things “one day a time.”

After being bailed out of jail by Carnes, she entered the Kolmac Clinic’s intensive outpatient program on the campus of Sheppard Pratt. She’s says she goes to A.A. meetings on a daily basis and that it was her 12-step sponsor who was with her all day at her criminal motions hearing.

She says that she believes in God and that everything happens for a reason, and if she had to go through this to become an example for others—a cautionary tale, as it were—so be it.

She admits that her arrest has been “devastating,” but that she has also gotten a great deal of support, receiving, she says, more than 200 messages and e-mails from friends, family, and colleagues. She does admit that she “lied to judges, lied to people, and lied to people that could’ve probably helped me.”

And whatever the outcome of her legal case, successful recovery from addiction remains a fraught road for anyone, requiring life-long care, as with other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, to which addiction treatment and recovery is often compared. Studies show that the majority of those in recovery do relapse, often requiring additional treatment. Fingerhood, the Bayview addiction specialist, estimates that about half of those seeking treatment for opiate addiction and also receiving drugs such as buprenorphine or methadone to stave off cravings, are able to attain “sustainable abstinence”—defined as one year clean and sober. Without medication help, he says, “It’s about 10 percent.”

As her nearly two-hour interview is concluding, Swerdlin says her sponsor tells her that it will take the same length of time off drugs, as on them, before she will even begin to feel like her self again, and she acknowledges that jail is a possibility. “I’ve never been in trouble and hopefully the 43 years before my addiction [will] all be considered,” she says. “I’m happy that my two children have good fathers. If I have to go to jail and do time, then I will do what I have to do.”

She intimates, however, that plea negotiations are imminent, and that disbarment with the possibility of applying for reinstatement five or so years down the line is a more likely scenario than a prison sentence.

If necessary, she says, she will re-invent herself.

“Who knows?” she says. “Maybe I’ll write a book about this one day if I lose my license.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This story will appear in our July 2014 issue, on newsstands later this month.

UPDATE (June 15, 5 p.m.):

Towson-based attorney Jill Swerdlin pled guilty to three charges this afternoon in Baltimore County Circuit Court related to the above story and faces jail time and disbarment, per her plea agreement with the Baltimore County State’s Attorney’s Office.

Swerdlin pled guilty to the distribution of buprenorphine, a drug used to treat opioid addiction, and the distribution of a controlled dangerous substance to a client incarcerated at the Baltimore County Detention Center. She also pled guilty to conspiracy to possess oxycodone.

The sentencing agreement, which will not be officially disposed until the end of July, calls for a maximum 5-year prison sentence for Swerdlin, with all but 18 months suspended. Swerdlin will not be eligible for home detention during her 18-month sentence, but will eligible for work release and may apply for parole. She also consented to disbarment as part of her plea.

Other plea agreement stipulations include three years of parole and probation, drug treatment, and random urinalysis.

Also as part of the deal, Swerdlin, a criminal defense attorney, agreed to meet with prosecutors and Baltimore County Detention Center officials to reveal everything she knows about drug smuggling efforts at the jail. Jason League, assistant state’s attorney for Baltimore County and lead prosecutor on the case, said changes have already been made since Swerdlin’s arrest to improve security at the jail.

According to the plea terms, Swerdlin may also seek to modify her sentence—essentially seek a probation before judgment final disposition—if she successfully completes all of her required stipulations, enabling her, potentially, to regain her law license down the road.

Three others indicted in the Swerdlin conspiracy case have already pled guilty and a fourth is expected to plea guilty next week, according to prosecutors. Six other people charged in the conspiracy still have their cases open.

“She’s different than just an addict because she had access to clients who were in a holding facility, and, as an officer of the court, she was abusing that access by smuggling drugs into prison,” League said afterwards. “Smuggling contraband into prison goes far beyond just that one client—many of the people there have drug problems and for them this is gold. So that becomes a huge problem and obviously, we have an obligation to uphold the integrity of our jails.”

League added that the broad prescription drug investigation that began in January of 2012, and led to Swerdlin’s arrest, remains ongoing.

–Illustration by Richard Mia

Update: This article has been updated to contain a sponsored link from recovery.org.