Walking into a brand new restaurant always fills us with a sense of excitement and curiosity. I hope the food is good. I wonder if we’ll get a good waiter. I hope the check isn’t too steep at the end of the night.Thoughts start to flood your brain as your stomach growls and you make your way to the table.

My husband and I find our seats at a communal table with a group of strangers and are greeted by the smiling face of 18-year-old Cee-Cee. “Welcome to The Bowl,” she says, holding a mini-clipboard dressed in a Washington Redskins jersey. We quickly learn that this is a Super Bowl-themed restaurant and all the wait staff, considerably younger than your average restaurant workers, are dressed in jerseys and referee-style shirts.

The one-room dining hall is packed and it’s not just because of the great food. This restaurant is a hot spot in the Carrollton neighborhood of Baltimore because of its unique format. Only open on the last Sunday of the month, the menus and themes are always rotating—and it’s totally free. Not to mention, the menu items—like buffalo cauliflower bites, potato skins, mac n’cheese, and fried chicken—are all created and prepared by the children bustling around at the restaurant.

No, this is not your ordinary downtown dining experience. What began as a small group of people going out weekly into the poorest zip code in Maryland to feed the community has evolved into a program that helps to bring culinary skills, job opportunities, food resources, and mentorship to the youth of Southwest Baltimore. This monthly restaurant is just one way they make it all happen.

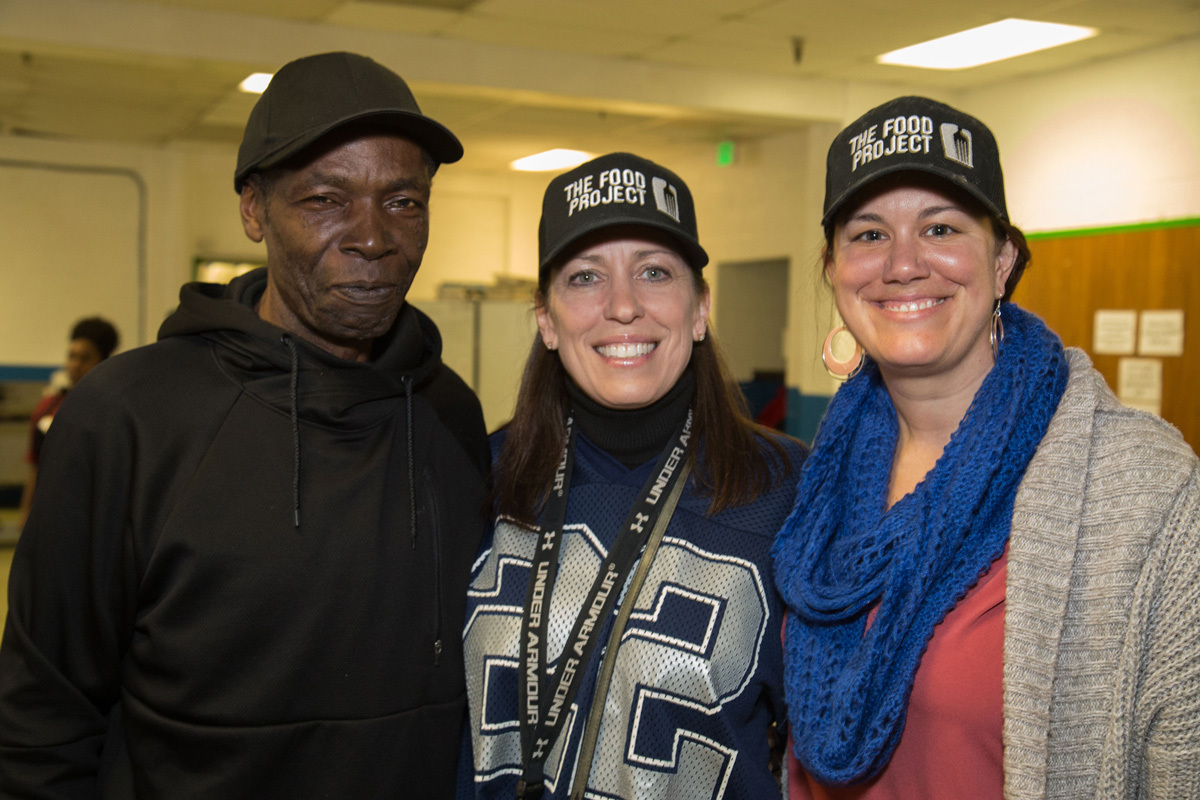

Housed in the the former Samuel F. B. Morse Elementary School is The Food Project, a subsidiary of local nonprofit UEmpower of Maryland that brings resources to underserved communities. The Food Project’s co-founder and director Michelle Suazo, together with her business partner chef Tom Koukoulis of Cafe Mezzanotte and other culinary professionals, set out to create a safe space for youth ages 8-18 to learn how to make healthy food and empower themselves at the same time.

With an idea in mind, along with willing volunteers, The Food Project was ready to get started in December 2016, but had no place to settle or call their own. That is until former councilwoman Rikki Spector came into the picture.

Right around that same time, Spector had been assaulted and carjacked by two young boys when she got a call from Suazo, asking if she would be willing to help the boys who robbed her. Suazo told Spector that she and her team had been trying for months to get help for the kids in the neighborhood where her assailants are from, but no one would listen. To anyone else, this would seem like a bold thing to ask of an 80-year-old woman who was just attacked, but lucky for Suazo, Spector was willing to step in.

“Apparently, they had been working with those boys for two years,” Spector said of UEmpower. “So we went to juvenile court to speak on their behalf. It didn’t take long to realize that the juvenile system is failing these kids and failing us.”

The median household income in the Carrollton Ridge neighborhood is less than $25,000. Nearly half of families live below the poverty line. Lead paint violations are more than three times the city average, and the children are nearly twice as likely to be murdered as anywhere else in Baltimore. Suazo found that, given the choice, the kids she encounters would prefer to be off the street and find other ways to make money. She just needed get them resources.

Spector, who is still well-connected in the city, remembered that when she was on the city council, Baltimore received a million-dollar tax bond to bring city schools “into the 21st century.” During this process, the city had 29 schools that were being declared surplus, and Samuel F.B. Morse was one of them.

“They were going to close this school and the rec center attached. That would have been a huge mistake,” Spector said. “I got my hands up in front of the mayor and the city council and said, ‘No, let us recycle this.’”

Suazo was able to get the space rent-free for the first year, complete with a kitchen, and a cafeteria. The rest of the building is home to the nonprofit “I’m Still Standing” that helps homeless veterans. After a major facelift with some fresh paint along with furniture and supplies donated by The Baltimore Sun, The Food Project now had a place to call home.

“Once we got the space, everything started to come together,” Suazo said. “It was really exciting to get all the kids together to help make this place their own.”

One of the first projects to come from their newly acquired kitchen was Seedy Nutty, a healthy snack made of peanuts, pecans, and pumpkin, sesame, and sunflower seeds. Seedy Nutty’s founder, Rosanne Skirble, discovered this treat during Passover visiting a cousin in Israel and, after marketing and selling herself for a few years, gifted the business to The Food Project to help with social enterprising for the children.

“My journey to retirement had left me with a business that turns out is a lot of hard work,” Skirble said. “I have sown the seeds for another entrepreneur who can take Seedy Nutty from its sweet spot among locals to a broader market looking for a healthier way to snack.”

This business is more than just the production of a snack. Suazo says the kids are learning about food safety, working on a team, marketing, and branding. The children do it all—they bake the snack, package it, and deliver it for resale. They even revamped the logo on the packaging making it unique, eye-catching, and a bit whimsical. Since moving under The Food Project, Seedy Nutty has grown and can be found at Whole Foods in Silver Spring, Center Stage, and Under Armour Brand House in Harbor East. But that is just the tip of iceberg.

“We also share a space with BeMoreGreen social enterprises, Healthy Juice People, Alkaline Bodies, and City Weeds who are teaching the kids how to make fresh-pressed juice, prepare meals, and grow microgreens,” Suazo said. “The idea is that the more social enterprises we can build out of the kitchen, the more jobs we can create for the community.”

When Suazo initially envisioned this program, she thought of food as a common ground that every person shared, no matter class or social status. With the help of volunteers, she provides not only a free meal each month, but also a weekly after-school educational enrichment for the attendees and also social services for the adults in the area.

“This program is unbelievable, if they had one of these in every corner of the city, it would make such a huge difference,” said Vicki Hannah, one of the volunteers at The Food Project. “This is a safe haven for the kids. There’s never been a place for these kids to gather and this fills that void.”

Each day, there is a different type of programming that explores a new aspect of the culinary industry. Mondays are reserved for learning about restaurant development and financial literacy, Tuesdays they host a guest chef like Catina Smith of Just Call Me Chef or Mente Lawson of Blackwall Hitch.

Wednesdays are a special treat for the children because they get to Be A Chef For A Day with chef Monica Lapenta, making pasta and sauces from scratch. This is also the day that behavioral therapist Jerel Wilson of the nonprofit “For My Kidz” comes to mentor the children with his weekly “Table Talks.”

“I help the kids stay engaged in something positive like workshops and also check up on their grades,” Wilson explained. “I mentor them and intervene on the negative stuff and try to help them through whatever issues that may arise. Living in this area can be really tough for these kids.”

Later in the week, local urban farmer and founder of City Weeds and #BeMoreGreen Dominic Nell, better known as Farmer Nell, comes and talks about the importance of nutrition and healthy living. Each week he brings in different fruits and vegetables and teaches kids about urban farming methods.

“Jerel and Farmer Nell are heaven-sent,” Suazo said. “The kids love them and they are also so good with them. They are great positive role models for the youth in this community who are typically used to seeing black men in a negative light.”

Fifteen-year-old Kalik Wise is one of those young men. His story is no different from the rest of the children that attend the program daily: he lives in a crime-ridden neighborhood with no real outlets except being outside or playing basketball. But he began coming to the program back in November and found that it was a great place to escape the troubles that he encounters in his neighborhood.

“I live in Southwest Baltimore and it’s just a lot of drama—shootings, drugs, people on drugs, all that stuff,” Wise said. “I keep coming back [to The Food Project] because it’s fun and we are learning cool stuff. If this wasn’t here, me and my friends would always be in trouble.”

Similarly, “Cee-Cee” Ward, our friendly server, began coming to the program just a month ago and has already been reaping the benefits. Every week, the volunteers help her with resume building and job searching. (She landed two job interviews as of press time.)

“I didn’t think I would like it when I first heard about it,” she said. “I had some friends that came and decided to check it out. It’s been a really big help for me. It’s also nice to get work experience so that, when I get a real job, I have the upperhand.”

Wise working at the restaurant. —E. Brady Robinson

Ward poses with her clipboard. —E. Brady Robinson

Ward, along with the nearly 30 other students in The Food Project, will get an opportunity to gain more experience with the next monthly restaurant on February 24. This month’s theme is called “Black Love,” in honor of Black History Month. As with previous restaurants, the children will use what they’ve learned in the program to create a menu and branding for their next group of patrons.

“It’s a gift that keeps on giving,” said Spector, who still works with her two assailants at The Food Project. “It’s been a journey. But this is what happens when you have resources for the kids in this neighborhood and allow them to take ownership.”