News & Community

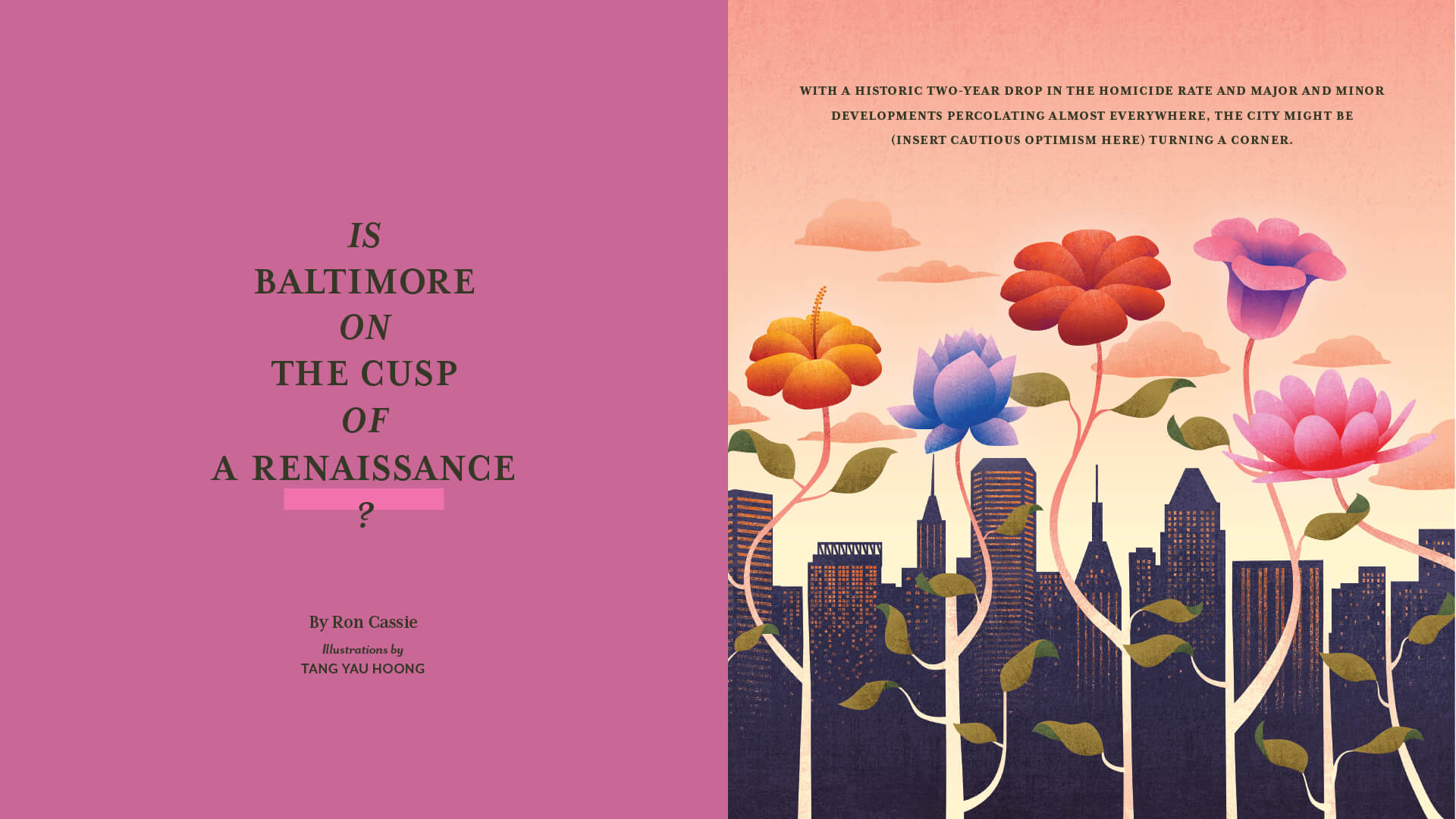

AT THE STATION NORTH event venue known as The Garage this past November, the nonprofit Youth Advocate Programs held a brunch to honor the recent accomplishments of its participants in the city’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy. It was not a particularly elaborate affair and not widely covered by local media, but the celebration did prove moving at times, and hopeful. It also offered a behind-the-scenes glimpse into the city’s still new—and by all indications, quite effective—approach to our half-century struggle with gun violence.

Youth Advocate Programs (YAP) is one of two nonprofits that actively engage with those identified by Baltimore police as having the highest risk of involvement with gun violence. Their staff, and the staff of a similar nonprofit, Roca, works with individuals with gang associations, ex-offenders, and others who’ve lost someone to gun violence—and could be considering retaliation. At the November event, attended by family members, Mayor Brandon Scott, and Stefanie Mavronis, the director of the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement, teenagers and young men shared stories of earning their GED, qualifying for a commercial drivers’ license, getting a job with DPW, moving into stable housing, rekindling relationships, and other milestones linked to reducing community violence.

“I come from hard times,” said one 15-year-old, recognized for his re-enrollment and perfect attendance after missing several years of his education. “We need more people doing this work,” he told the audience, quietly gesturing to YAP life coaches, many of whom live in the same neighborhoods and share similar life experiences with those they serve.

The current Gun Violence Reduction Strategy, put forth by Mayor Brandon Scott in his first term, is the city’s first comprehensive public health approach to gun violence. Individuals determined by BPD intelligence to be most likely to commit gun violence—or be victimized by gun violence—receive an intervention and offer of services and support. As of the end of 2024, 201 individuals have enrolled in life-coaching services through the Group Violence Reduction Strategy effort.

Of that group, 94 percent have not recidivated, and 91.5 percent have not been re-victimized, according to the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement.

First implemented as a pilot project in the Western District in 2022, and still not quite citywide, the Group Violence Reduction Strategy is sometimes described as “focused deterrent,” highlighting critical coordination with the BPD and the City State’s Attorney’s Office. (The intervention offers a variety of support services in exchange for staying out of trouble, representing a “carrot and stick” deal with GVRS targeted participants.) It has been credited by at least one study with helping drive a decrease in local homicides, which this past year saw a historic 23-percent decline.

That drop, on the heels of a 20-percent decrease in 2022—a combined 40 percent-plus reduction over the past two years—is such stunning, inspiring, and trend-shifting news after a decade of unprecedented violence that the significance is difficult to put into words.

Y ITSELF, the dramatic two-year decrease in Baltimore’s homicide rate is a story now receiving national attention. But it is hardly the only good story unfolding in The Greatest City in America, as our park benches have proclaimed, some might say ironically, for 25 years. There are major and minor developments percolating almost everywhere, and not just in the sparkling new “Gold Coast” waterfront neighborhoods of Harbor East, Harbor Point, and the Baltimore Peninsula.

On the west side, a transformed Lexington Market reopened in 2023 after a $45-million renovation. The massive makeover and recreational update of the lake at Druid Hill Park is almost complete. Off North Avenue, a whole new mixed-use neighborhood, Reservoir Square, is being developed in a space formerly known as the “murder mall.” Upton, Edmondson Village, Park Heights, Pimlico, and Penn North—part of the new Pennsylvania Avenue Black Arts & Entertainment District—are all seeing new infrastructure and community investments.

On the other side of town, new homes and newly rehabbed homes have revitalized the east Baltimore neighborhoods of Oliver, Johnston Square, and Eager Park. Closer to downtown, Pigtown, Seton Hill, and Hollins Market, whose revamped historic market reopened in the fall, look livelier than they have in decades. Meanwhile, the huge Fells Point-adjacent Perkins Square project, replacing the area’s worn-out 1940s public housing, is well underway. New housing construction has also begun in nearby Somerset and Oldtown. It’s easy, too, to take Remington’s remarkable transformation for granted. But it was not that long ago that this vibrant, walkable, mixed-use neighborhood was shedding population faster than the city as a whole.

There is so much happening that it’s impossible to include everything. It’s also necessary to note that the construction of affordable housing—an antidote to rising rent and single-homes costs—is long overdue. On top of those promising new home and commercial endeavors—stalled over the past decade and a half by the housing crash of 2007 and the subsequent turmoil following the death of Freddie Gray eight years later—there is what can best be described as the civic pride stuff, too. The kind of public institutions and cultural infrastructure that ultimately might make Baltimore more of a Fortune 500-type player in the 21st century, attracting the private sector investments witnessed in cities like Austin, Charlotte, and Nashville.

We’re thinking of the makeover of Harborplace, approved by voters in November; the wildly successful $250-million redevelopment of CFG Bank Arena, which now attracts A-list talent the entire calendar year; the redevelopment and expansion of beautiful Penn Station; as well as the rapid rise of the Baltimore Peninsula—the corporate home to Under Armour and a modern, mixed-used neighborhood built upon the former brownfield previously known as Port Covington. There is also the combined $600-million renovation funding for M&T Bank Stadium and Camden Yards, the respective homes to our NFL and MLB playoff teams, and of course the $2-billion rebuilding of the Key Bridge, a symbol of the economic engine of Maryland—the Port of Baltimore—and representative of a crucial coming together of the city, county, and state in the face of tragedy.

But let’s also be honest. None of this is to say that Baltimore is suddenly the land of milk and honey. While the homicide rate is down, it remains way too high by any humane standard. The city’s tragic opioid epidemic ranks among the worst anywhere, as does the air pollution crisis in South Baltimore. Maryland’s operating and transportation budgets are in such dire straits that state funding needed to do things like maintain the city roads, expand public transit, and increase school funding is not likely forthcoming any time soon. Even with Baltimoreans in charge of the Senate majority and seated in the Governor’s Mansion.

The election of Donald Trump likely won’t benefit Baltimore, either. Not with the amount of federal jobs potentially on the chopping block, his plans to target immigrants—a growing presence and critical economic component in the city—and the $2 billion of federal money required to build the east-westRed Line.

For anyone who has been here since say, the 1980s—witnessing the exciting development of the Inner Harbor juxtaposed with the loss of the 100,000 manufacturing jobs last century—it’s often seemed like the city has taken one step forward and two steps back. In that regard, we might finally be over the hump in terms of 60-plus years of de-industrialization, disinvestment, and population decline. In 2023, Baltimore City earned a federal “Tech Hub” designation as part of a competitive initiative to expand manufacturing across the country.

Overall, last year, population fell again, but that’s not anomalous—it fell in Baltimore County and across the state, too, and it doesn’t necessarily portend future losses anymore. The number of households in the city rose last year—an indication young people want to live here—a good sign for the future. A couple of other positive signs: Using millions in American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding, the city has finally begun making significant progress in bringing down the vast quantity of vacant properties in Baltimore. It’s progress that should continue with Gov. Wes Moore’s recent announcement of more than $50 million in awards through the Baltimore Vacants Reinvestment Initiative. The city also recently won a $85-millon federal grant to help transform the blighted “Highway to Nowhere.”

We even reelected a mayor for the first time in two decades.

And while we don’t not want to quibble with Mayor Scott’s “Experience the Renaissance” second inauguration theme—part of his job is cheerleader-in-chief—it does seem a bit premature.

Maybe, however, it is time to insert some cautious optimism.

O STEP BACK for a moment, it is important to keep in mind that no city shrinks elegantly. Every older city has faced the enormous challenges associated with suburban flight last century. Detroit, St. Louis, the entire AFC North—Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and Cincinnati—all lost a greater percentage of its peak population than Baltimore.

Through it all, there has always been much to love about Baltimore. Beyond our world class cultural institutions and world class universities, the best crab cakes anywhere, our iconic rowhouses, marble steps, and incredible architecture—there are our resilient, unique neighborhoods.

With those neighborhoods in mind, it is the renovations at nearly 30 public schools, the construction of new school buildings, as well as the welcome addition of brand-new recreation centers around the city—after decades of closures—that are perhaps the most promising developments. Where else lies the city’s future, but with our youth, who, more than anyone, deserve world-class facilities.

Below, we offer conversations, edited for clarity and length, with a half-dozen civic leaders from the fields of public safety, business and commercial development, arts and culture, higher education, and philanthropy.

We asked them for their opinion on the state of the city—or at least their corner of it. With some, we asked specifically if they felt like Baltimore was on the cusp of a renaissance, to use the mayor’s word. Of course, the question remains open to interpretation. How will we know for sure, anyhow?

Is it a single metric, like population or economic growth? In 2022, the city’s economic growth surpassed the state’s overall economic growth rate, posting the eighth best number in the country for a jurisdiction our size, though it slowed down to a more pedestrian GDP growth last year. Another example of one step forward, one step back?

More likely, it’ll be many things and a few more years, if not a generation, before the full picture becomes clear and we’ll know whether or not a stable foundation has been built.

STEFANIE MAVRONIS

PUBLIC SAFETY

The historic 23-percent decrease in homicides last year, following a 20-percent drop in 2022—marks a monumental shift after a record-breaking decade of violence. Stefanie Mavronis, the director of the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement, which coordinates the city’s widely credited Group Violence Reduction Strategy (GVRS), talks about how it works.

he way it looks for us [the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement], is that every week we have a violence review with the Baltimore Police Department. We go through every single homicide and shooting that took place the week prior. Based on the intelligence from BPD, we understand if this was a group-involved incident—and therefore eligible for GVRS attention and resources—or was it, let’s say, domestic or intimate-partner violence? If we see there is a group association involved, those individuals will be eligible for some kind of intervention, although we check with the City State’s Attorney’s Office to also see if they are the target of an ongoing investigation.

Really, the purpose of the review is for us to learn what motivated the incident and who is committing violence on behalf of each other. Is it a group of friends or five individuals who maybe they don’t consider themselves a gang, but we know based on police intelligence they’ve engaged in violence together, or were associated in an incident? Or, have they been the target of victimization? If one person becomes a homicide victim, then these four or five close associates are people that we’re interested in connecting with [given the risk of retaliation].

So, this is fundamentally an intervention strategy involving a person of interest, meaning a perspective GVRS participant, after we locate them on the street in the days after an incident. Once they’ve been identified and engaged, we’ll say, “We see that your associate was connected to this [incident], and we don’t want this to be the end of the road for you. We want to give you an opportunity to receive services. Can we work together? Can we connect you with a life coach? What do you need to make a change and not act on whatever plans you may have had to retaliate?” If there’s someone who did not accept services, and is incarcerated and preparing to be released, we will re-engage with that person because they’re on our radar and we want to make sure they get support and don’t end up back in jail.

What does success look like, in terms of these interventions? And can you tell us about the partners in the GVRS?

Since January 2022, when we initiated the strategy as a pilot in the Western police district, we’ve enrolled 201 people at the highest risk of being involved in violence. That life-coaching work is split between YAP [Youth Advocates Program] and Roca, who works with the young men ages 16 to 24. We know that 91.5 percent of people who have been enrolled in life-coaching services through the Group Violence Reduction Strategy have not been re-victimized and 94 percent have not recidivated. Again, these are the people who BPD intelligence shows us are at the center of gun violence in the Western and Southwestern, Central, and Eastern Districts, where GVRS had been expanded.

The BPD and City State’s Attorney’s office both play significant roles, obviously.

Overall, the most significant thing about the GVRS is the unprecedented level of collaboration across agencies. Everyone is moving in service of a common goal, which we have not often seen before. I think that, and being very clear about our specific roles, is the key reason why we’re seeing the success that we're seeing.

—COURTESY OF GENSLER & ASSOCIATES AND MCB REAL ESTATE.

COLIN TARBERT

[RE]GROWING THE CITY

The CEO of the Baltimore Development Corporation, Colin Tarbert is responsible for retaining and attracting businesses, growing jobs, and increasing investment in city neighborhoods. He discusses Baltimore’s economic trajectory and recent development projects—and if the city has turned an economic corner.

here’s still the Rust Belt connotation with Baltimore, but we’re in a much different geographical situation than Toledo or someplace [like that]. Being on the East Coast, we’re certainly poised for growth. It is hard, but I try to explain this to people who are maybe from D.C. who come here and are like, “Oh, Baltimore, it reminds me of D.C., which transformed dramatically. It could happen here.” I don’t think Baltimore is different in the sense that it can’t happen here, but we really are a more authentic city, we are really a city of neighborhoods, and a lot of folks who live here have this long history. I don’t want to contradict the mayor, but “renaissance” is a word that’s been used before, especially during the ’80s. If anything, my experience has shown me that we can make steady, incremental progress, but the city’s transformation is not going to happen overnight.

Economic development is just less sexy. It’s day in, day out progress that accumulates over time. Think of the Inner Harbor redevelopment, which began under Mayor Theodore McKeldin and William Donald Schaefer implemented. That was dramatic when it came together, but it wasn’t felt citywide. Kurt Schmoke planted seeds for Harbor East and Martin O’Malley took over, and then Harbor Point comes together in the transition from O’Malley to Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. Then, of course, there’s the development of the Baltimore Peninsula, which began under Rawlings-Blake and is happening now. Large-scale projects happen over administrations.

Beyond the major developments you just named, where do you see encouraging signs? If we’re not quite experiencing a renaissance, are their reasons to be cautiously optimistic?

Well, the waterfront area over the last two decades has been transformed. What I’m seeing now is that same type of energy and excitement, maybe not on the same scale, throughout different neighborhoods in the city. Remington has been a big success story. The development in East Baltimore [around Johns Hopkins Hospital] had its fits and starts. But the blight that was there 15 years ago is all gone and now there’s $400,000 townhomes and more investment is following.

Same now with the west side. There’s a lot of small-scale redevelopments happening in pockets. You can look at North Avenue Development Authority and the funding behind that effort. You can look at The Uplands [where Phase II of the affordable West Baltimore housing development was just completed] and at Edmonson Village, which hadn’t seen much positive news in recent years and is getting two new grocery stores.

I think much of the work by the Neighborhood Impact Investment Fund [launched in 2018 to provide access to capital for under-resourced neighborhoods] is flying under the radar. It’s been hugely significant, leveraging, for example, hundreds of millions of dollars into projects like Reservoir Square, which used to be known as the “murder mall.”

In that way, the death of Freddie Gray and the unrest was a wake-up call, that maybe the trajectory that we were on, while it was positive in many economic aspects from 2010-2014, wasn’t as comprehensive and as thoughtful and as equitable as it should have been. It brought a lot of private sector and institutional leadership to the table that were sort of engaged, but didn’t realize how divided or inequitable the city really was.

—PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRISTOPHER MYERS

SHANAYSHA SAULS

SHARED PURPOSE

Led by Shanaysha Sauls, the first person of color and first woman to lead the organization, the Baltimore Community Foundation (BCF) manages more than $300 million in assets, representing more than 940 charitable funds. We asked her about the role philanthropy plays in moving the city forward.

want to say upfront that philanthropy is not a panacea to solve Baltimore’s problems. But I do think we [and other foundations] have flexible capital, and maybe with that flexible capital comes a higher appetite for risk. Essentially, we can serve as a proof of concept for an idea that requires significant public capital. A lot of times that’s the role that we serve—as a catalyst for ideas. We can try something and then partner with other foundations, private capital, and ultimately, the public sector to make it work.

For example, local foundations came together to support the creation of the Mayor’s Group Violence Reduction Strategy (GVRS). When he was mayor-elect, Brandon Scott had begun talking about the importance of trying to bring what was called “focused deterrence” to Baltimore and the way that philanthropy could help that effort. And so, a small group of us in the foundation world decided that we would support bringing it in, obviously under the mayor’s leadership and in coordination with the other law enforcement bodies. I won’t overstate it, but philanthropy was a huge part of the GVRS story. [The city’s Gun Violence Reduction Strategy is credited with helping bring down the homicide rate over the past two years.]

Where else have philanthropic efforts made a transformational impact?

I think of initiatives such as ReBuild Metro in Oliver and more recently in Johnston Square. That’s been individual private capital and private philanthropy working with grassroots organizations to figure out how to reinvest in those communities without displacing the residents. And making sure that residents who’ve been in that community for a long time can participate in the revitalizing of their community. [BCF also makes small neighborhood grants, as for the mural below.]

Another example is the repurposing of community assets that aren’t necessarily on a grand scale but are absolutely important, anchors like the Creative Alliance. That was a partnership between community members and private philanthropy that created an arts asset in Southeast Baltimore. There has been a similar attempt on the west side in recent years with the Ambassador Theater, that’s had its fits and starts. I don’t suggest that it’s all roses and rainbows.

What does the re-election of Mayor Scott and political stability at City Hall mean for the philanthropic community?

I can only speak specifically for BCF, but we exist for Baltimore to win, and we want to partner with the civic, political, and business leaders. That means we’re going we look to the mayor’s leadership. We’re going to pay attention to the issues that he believes are important to move the needle and we’ll look for opportunities to partner on those issues. No matter where you stood politically during the election, we should all feel some assurance that we have re-elected a mayor and we haven’t done that in 20 years, a generation. No major city has stabilized and revitalized itself and experienced a renaissance without continuity in leadership.

Because of the intervening years of uncertainty and instability and some cringe-worthy headlines, there’s often been an impulse that we need to change everything and go in a completely different direction. One thing the foundation community can do is be a responsible partner in thinking about how we do honor the past—be clear-eyed about the past and its challenges—and weave the past, the present, and the future together?

MARK ANTHONY THOMAS

THE NARRATIVE

The Greater Baltimore Committee’s new CEO, Mark Anthony Thomas, has spent the past year working on a strategy to revamp Baltimore’s image and attract investment. With experience leading economic development strategies for New York, Los Angeles, and Pittsburgh, Thomas says the city needs to tell a new story.

ne thing to keep in mind is that cities never evolve back to what they were. The Greater Baltimore Committee [recruited] me in Pittsburgh, which had seen its steel industry [and population] collapse, and whose version of the GBC aggressively helped to reinvent Pittsburgh’s economy. Most people will say they turned the corner in terms of the national narrative. The branding work that I did there was to create a new story and show that there is all this future activity—tech, robotics, virtual reality, chips, AI—that is alive and well and give it definition. The “Next is Now” campaign promoted Pittsburgh as an attractive place to live, work, and play. There’s a popular district now that’s being formed around the Mexican War Streets neighborhood that will connect a lot of their arts assets.

Today, Pittsburgh attracts three times as much venture capital as we do in Baltimore. They are arguably over whatever the hump is that you need to be over. If anything, the areas that need work are the surrounding counties.

GBC hired Resonance and Ipsos, the global place branding and market research companies, to assist this rebranding of Baltimore, and they’ve shared some interesting data and information, to say the least. They say the city needs to stop defending itself from the image of The Wire, that outsiders have a better perception of the city than Baltimore metro area residents, and that a reputation as a great place to live, work, and play drives investment more than lower tax rates, housing costs, or any other factor.

A sales pitch for the city is long overdue. Even during this process, the research is saying that based on the number of institutions and arts, the access to the waterfront, the walkability of the neighborhoods, the restaurant density, the culture that is all around, Baltimore is a very livable city, and no one knows it. If I take an entrepreneur around the city for two days—minus the vacant buildings—they feel like Baltimore is a city that has a lot to offer. If you’ve been to Upsurge’s Equitech Tuesday, you see the young startup community that comes together, and you feel like you’re in a vibrant place. But you don’t know that unless you’re exposed to it. We also need regional consensus around our pitch, and the suburban counties are in alignment, understanding that it’s one labor market, one integrated future.

Suburbs, whether it is Miami or Austin, sell their proximity to its city’s assets. Here, it’s almost like they’ve been degrading the city’s assets. This a moment where that can change.

By rule, business investment and expansion are highly sophisticated. There are billions of dollars that flow between states, which are oriented or directed by an industry of location advisors and, unfortunately, that competition has largely existed without Baltimore being a major player.

As far as The Wire, it’s the economic story at its core that’s been more damaging than the crime story. The city is a place that lacks opportunity, where the conditions are so poor, there’s blight, etc. We can get ahead of The Wire. I believe that. I’ve studied what Detroit has gone through since bankruptcy and the progress they’re making. The Economist had a piece saying it is inarguable that they turned a corner. They had 700,000 people there for their huge NFL draft event last year.

CARA OBER

CITY OF ARTISTS

Baltimore has long celebrated its diverse culture—our distinctive neighborhoods, rich architecture, civil rights legacy, and Chesapeake cuisine. BmoreArt founder Cara Ober explains why Baltimore should also be recognized as a City of Artists, coincidentally, the title of a recent coffee-table book put out by her magazine.

unpacked this a bit in the introductory essay for City of Artists. First, the 16 writers and 16 artists in the book offer proof that Baltimore is a city of artists. They’re novelists, journalists, art historians, and poets. We intentionally selected writers whose careers were much larger than Baltimore, and we similarly selected 16 visual artists whose careers were at that same professional level. So, it’s writers and artists whose careers are national or international, but they choose to live in Baltimore. The initial lists were much longer than 16, but we culled and paired writers and artists who shared a similar aesthetic or concept behind their work.

Part of this pairing was about who lives in Baltimore and why. That’s the question the book asks. We asked writers to share a story about a specific place in the city, and then to explore what that means to them [and how it shapes their ideas and work]. They each picked a different place and, in most cases, dove into the history of that place, its social, political, artistic context, and presented an argument about why it matters and what it means to them. Our city is steeped in history, which I see largely as a positive thing, but many of them are presenting issues and problems and conflicts in the city and showing that those aspects of Baltimore life enrich one’s art practice, and not just the writers, obviously. Artists imbue it with meaning and urgency.

What do you see as the city’s strengths and weaknesses in terms of creating a full-flowered arts and cultural renaissance?

The price of real estate is what makes Baltimore more appealing to artists than D.C. or New York, for example. You’re able to have space to realize your ideas. The thing we’re missing is that professional infrastructure. We’re missing the businesses [that fund the arts], we’re missing the commercial gallery system, the major art market that comes with communications and marketing—and the professionals adept at cultivating collectors. Artists are forced to take all of this on here, which is why many things tend to stay hidden, insider-y, or at certain professional level. We’re missing those parts of the cultural ecosystem that New York and other cities have. This is a conversation that I’ve had with arts funders and professionals working in nonprofit sectors in other cities. There are more [big] businesses, for one, and those businesses actually support the arts as well. In Baltimore, who are the big businesses? What are we are making here?

Once we have a new administration in Washington, knowing how many jobs in the region are dependent upon the federal government, it’s going to be interesting to see what the impact is locally.

Baltimore, however, is also a place where people who stay here, stay here for a reason. There are the graduate schools, there is the “meds and eds” aspect. But others who choose to stay are people who have a desire to build something—creatively, economically—or just build community. It would be great if we had a corporate support whose philanthropic funding could grow and sustain an arts ecosystem. It would be great if there was the kind of infrastructure that links everything together. I think that’s what needs to happen for there to be an actual renaissance.

—PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRISTOPHER MYERS

DAVID WILSON

BRAIN GAIN

With construction booming at Morgan State, enrollment at an all-time high, and the school on the cusp of the highest classification for research universities, we asked President David Wilson to talk about the HBCU’s remarkable growth and what it means for Baltimore.

organ is in the most transformational period in its history and that’s saying a lot. Our institution has been around for 158 years. We’ve grown from 7,000 to 11,000 students—from nearly every state and more than 70 countries—and that growth is across the board, the undergraduate, masters, and doctoral levels. People now understand all over Maryland, the United States, and indeed all over the world that a Morgan education can take them anywhere they want to go, and that’s important. As my dad would sometimes say to me, “Son, the cat is out of the bag.”

Updating the campus itself, “our spaces and places,” has been a majority priority during my 15-year tenure. We’ve held five ribbon-cutting ceremonies in recent years for newly constructed and/or renovated and reopened facilities, including Hurt Gymnasium, the new Health & Human Services Center, and three residence halls. The standard here is clear, and that’s to be an institution that is comparable in every way—functionality, amenities, research labs—to any college in the state and any college in the nation.

Regarding our research, Morgan is on the cusp of joining the University of Maryland College Park and Johns Hopkins, and of recent note, UMBC, as the only R1 research institutions in the state—the highest classification. For further context, when I first arrived, we were generating $18-19 million a year in research grants, and we’re on track to surpass $100 million next fiscal year. Also, in 2023, Morgan set a record among HBCUs by obtaining 13 patent awards in a calendar year, ranking in the top 100 universities in the country. Keep in mind, Morgan is really punching above its weight class. If you look at the University of Georgia, for example, they received $570 million in research grants, but only produced two more patents. Meanwhile, numerous professors have become national fellows and been inducted into national academies.

So, how does Morgan’s growth and success translate to the broader city and metro area?

The impact of Morgan in Baltimore is felt on several dimensions. The last study we did showed Morgan directly contributes to roughly 8,000 jobs and $800 million in tax revenues coming to Baltimore, with an economic impact of $1.5 billion. In other words, Morgan has added to the economic foundation of Baltimore City. Secondly, there is the “innovative economy” impact—17 percent of our graduates work in STEM fields, overwhelmingly in Maryland. At the same time, the university has one of the best performing arts programs in the nation [including Morgan’s internationally celebrated choir and Magnificent Marching Machine band] and our business school was just ranked No. 60 by Bloomberg Businessweek, the only HBCU ever to crack that list.

When you put all these things together, Morgan can play a critical role in elevating Baltimore City to a point where it could resemble Route 128 outside of Boston, which [because of its great universities] became a tech, biotech, and entrepreneurial hub, a sexy place where people want to go to school and stay after they graduate because of its energy and creativity.

For Baltimore, it’s about harnessing the talent of these newly minted graduates and up-and-coming professionals who want to be a part of something like that. Morgan is one of the institutions that could be central to building that kind of an ecosystem in the city.