Our city's historic built environment becomes more inspiring with each passing generation.

News & Community

Baltimore The Beautiful

Our city's historic built environment becomes more inspiring with each passing generation.

Residents of Mount Vernon Place were not happy in the spring of 1907. Three years earlier, they had successfully pushed for legislation prohibiting buildings taller than 70 feet within one block of their prized Washington Monument, which the Municipal Arts Society of Baltimore put forth as “one of the three finest columns in the world, ranking with Trajan’s Column in Rome and the July Column in Paris.” Now, however, the owner of the 69-foot Washington Apartments, the gorgeous Beaux-Arts building which stands to this day on the monument’s northwest corner, had gone to court in hopes of erecting an 8-foot addition. Described as one of the first zoning laws in the U.S., the “anti-skyscraper” decree withstood the constitutional challenge, but it would prove far from the last threat to the character of the cobblestone square and the city’s most elegant architecture.

Another apartment developer challenged the ordinance in 1929. Eleven years later, the chairman of the State Tax Commission proposed repealing the height limit in the name of increasing tax assessments. In 1944 and 1957, officials made plans for crosstown highways just south, and north, respectively, of the square’s Frederick Law Olmstead-designed parks. In the same mid-century era, Mayors Thomas D’Alesandro Jr. and Theodore McKeldin each formed committees whose proposals called for the demolition of many of the historic structures facing the park—in one case to make room for a 22,000-seat arena.

Historic Mount vernon place, springtime, 1948. library of congress; A. Aubrey bodine

Each time, neighborhood opposition galvanized to block the plans. Thank God.

What is the value in paying attention to our architecture and built environment? Each structure (and monument) has a story, of course—who designed it, its aesthetic influences, who lived and worked in its halls, and the initial purpose it served, which we know often changes over time. Century-old warehouses become apartments, rail yards become ballparks, cotton mills become award-winning restaurants, schools become art studios, churches become breweries, and breweries become office buildings. In turn, these structures tell the stories of our neighborhoods—their evolution and, at times, devolution. Our buildings are also repositories of our personal memories. Visit the church where your parents or grandparents married, or their school or place of work, and expect a flood of emotions. Maybe it goes without saying, but it is the city’s architecture, more than anything else, that is responsible for our shared sense of place. Most of the time, it’s a history worth fighting for and preserving, as Mount Vernon’s residents have known all along.

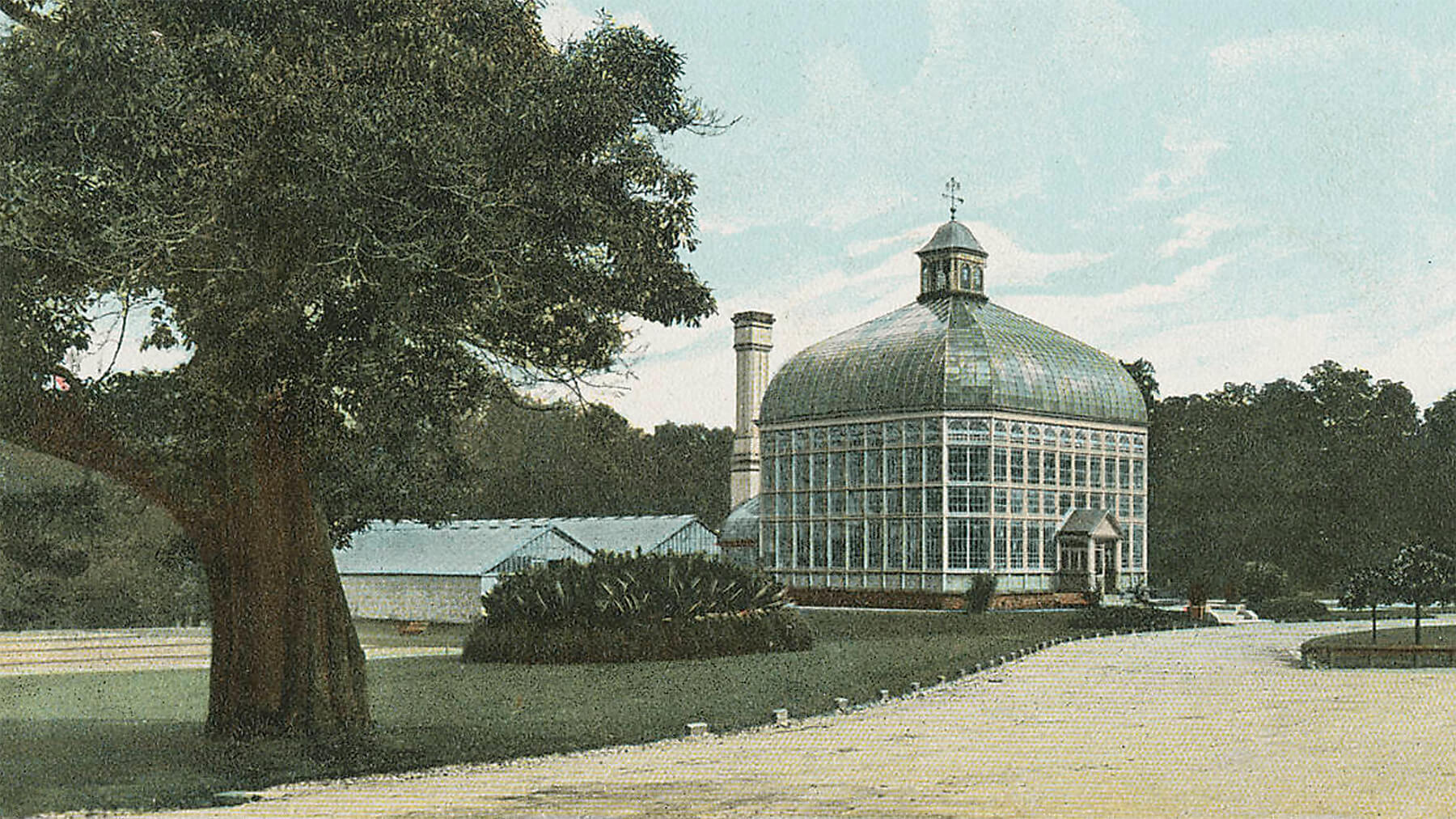

Rawlings Conservatory & Botanical Gardens, established in 1888. Published by the Souvenir Postcard Co, NY ca. 1907

“When we got married, my wife was living in an apartment at Mount Vernon Place, and I owned a house in Federal Hill. So we decided she should move in with me,’” recalls Walter Schamu, founder of the Baltimore Architecture Foundation. “She had agreed, but not before she said, ‘You are taking me away from the most beautiful neighborhood in the country.’”

Centered around the monument and its radiating parks—all of Mount Vernon Place has been designated a National Historic Landmark—are the polychromatic, 1872 Gothic Revival Mount Vernon Methodist Church and the spacious Italianate residence at 11 West Mount Vernon Place, a wedding gift from B&O Railroad president John Garrett to his son and daughter-in-law. The mansion has served as home to the Engineers Club since 1961. Also: the Peabody Institute’s breathtaking library, The Walters Art Museum, the renovated Hackerman House, and The Stafford, the 1894 former hotel and home to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Nearby, the high-Victorian Belvedere Terrace rowhouses, completed in 1881, sit handsomely in the 1000 block of North Calvert.

There is more architecture to admire in the surrounding neighborhood. Enoch Pratt’s renovated cathedral of learning, the magnificent Baltimore Basilica, restored in 2006, the Beaux-Arts-style Belvedere Hotel, and the Gothic-Revival First and Franklin Presbyterian Church are all treasures.

the 1929-built art deco skyscraper at 10 Light Street. From the collection of the Enoch Pratt Free Library.

Baltimore Heritage executive director Johns Hopkins notes midtown’s Old World feel is due to a confluence of events. In the years after the Civil War, he explains, Baltimore was one of the largest cities in the country and a commercial powerhouse, attracting wealthy families and philanthropists to Mount Vernon’s high-on-the-hill location at the same time American architecture was coming into its own. That said, there’s also much to appreciate in eclectic, broader Baltimore: the B&O Roundhouse, the Rawlings Conservatory & Botanical Gardens, Camden Yards, the iconic rowhomes at underrated Franklin Square, 10 Light Street—an Art Deco masterpiece—and the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, the first major downtown building designed by African-American architects (Phil Freelon, who died this year, in collaboration with local architect Gary Bowden).

Hopkins believes Baltimore’s architectural legacy and historic neighborhoods are its greatest assets, along with the waterfront, and that their preservation points a way forward, both in terms of maintaining the city’s density and attracting new investment. “Certainly, we’ve seen it around the harbor, and now we are seeing it happen in other historic neighborhoods,” Hopkins says, referring to the ongoing revivals of Remington, Reservoir Hill, Hollins Market, and Pigtown, among others. “When I look at Baltimore, I see how our past can help us turn a corner,” he says. The 2,500-plus visitors to Doors Open Baltimore, organized each fall by the local chapter of The American Institute of Architects, attest to a renewed and meaningful interest in the city’s architectural history.

What follows on this page are two photo essays celebrating examples of Baltimore’s exquisite architecture—second to none in the United States—and the people and stories behind those buildings.—Ron Cassie

city hall

100 N. Holliday Street

Completed between 1867-1875, the official seat of government barely survived the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904–spared by a single block–and remains one of the most eclectic buildings in the city. An early example of French Renaissance Revival in the U.S., its grand design was the handiwork of a then-22-year-old architect named George Frederick, who had won his first big commission. Among City Hall’s exterior highlights: the tall, multilayered, central dome, one of the finest specimens of ironwork in the country; the mansard roof; the building’s flanking, symmetrical wings; and the first-, second-, and third-story pilasters, detached columns, and deeply recessed windows, which themselves are surmounted by semicircular arches and elaborate keystones. The four aboveground exterior walls are all faced with white magnesia limestone, popularly known as “Beaver Dam Marble,” culled from the quarries near Cockeysville. One more detail: After public outcry over its cost, construction came in $200,000 under budget.

The Equitable Building

10 N. Calvert Street

The steel boom of the late 1800s brought about Louis Sullivan’s groundbreaking skyscrapers, and while the famed architect was building up the Chicago skyline, Joseph Evans Sperry was trying his hand at the same in Baltimore. While he’s best known for his nearby Bromo Seltzer Tower, Sperry is also responsible for this steel-framed colossus that exemplifies the palazzo-style construction that was popular near the turn of the 20th century. Originally built in 1891, its interior (which once housed offices, a billiards hall, Turkish baths, and other attractions) was gutted by the Great Baltimore Fire just 13 years later, but the frame and impressive facade withstood the flames, and the building now lives on as the luxurious Equitable Building apartments.

The Faust Brothers Building

307-309 W. Baltimore Street

Tucked unassumingly among the parking garages and storefronts that surround Royal Farms Arena is a 145-year-old structure that might look more at home in SoHo than along Baltimore Street. The Faust Brothers Building, also known as The Trading Post after a mid-century riding store once housed there, is a vestige of Industrial Revolution-era design built by Benjamin F. Bennett, who was also responsible for Broadway Market and Lovely Lane United Methodist Church, among other local treasures. Its cast-iron frieze, Corinthian columns, and detailed cornices continue onto the Cider Alley side of the structure, granting it the distinction of being the only known building in the world to have such a facade on both the front and back.

“The longer I live, the more beautiful life becomes. If you foolishly ignore beauty, you will soon find yourself without it.”

—Frank Lloyd Wright

george peabody library

17 E. Mt. Vernon Place

Walking into this 1878 cathedral of knowledge, whether for a day of research or a fairy tale wedding, feels like a trip back in time. It’s a master class in dignified opulence, with Baroque, Rococo, and Gothic details, gold leaf, and patterned marble somehow fitting seamlessly into one unified design. Perhaps philanthropist George Peabody’s finest gift to Baltimore, the public space also includes five soaring stories of cast-iron, Neo-Greek columns and a latticed skylight topping off the 61-foot ceiling. The plans for its grandeur were introduced, fittingly, with grand language. Such a gift, wrote the National Intelligencer when Peabody’s donation was announced in February 1857, “sheds a lustre not only on the name of the donor, but also on that common humanity which it adorns.”

The engineers club of Baltimore

11 W. Mount Vernon Place

What better stewards could there be for a Gilded Age mansion than the city’s engineers? The Engineering Society of Baltimore has called the Garrett-Jacobs Mansion, better known as the Engineers Club, home since 1961 and has earned praise for the maintenance of and restoration efforts toward everything from the impressive Mount Vernon Place facade to the Tiffany glass dome lording over its now-iconic spiral staircase. While the view from the street is lovely, it’s the interior of this stately home that shines. Detailed wood paneling, damask walls, gold trim, and herringbone floors make it easy to imagine socialites wandering the halls in their finery during one of Mrs. Jacobs’ legendary parties.

A Finer View

PHOTOGRAPHY & text BY GREG PEASE. edited by christine jackson

Baltimore’s rich architectural heritage has influenced and inspired my photography throughout my professional career. The photographs that follow are part of a larger collection depicting Baltimore’s past and present urban personality. I created these images to pay homage to the visionary architects and urban planners who shaped our city and bring attention to Baltimore’s physical splendor. The buildings featured here are some of the finest architectural examples from the 19th and 20th centuries. Scattered across Baltimore, these structures built for commerce, worship, and government helped define a proud, bold, imposing American city.

Spires of Bolton Hill, from left: Eutaw Place Temple, 1305 Eutaw Pl., Completed: 1892; Corpus Christi Church, 110 W. Lafayette Ave., Completed: 1891; Bethel A.M.E. Church, 1300 Druid Hill Ave., Completed: 1868; Brown Memorial Presbyterian Church, 1316 Park Ave., Completed: 1870.

10 Light Street, Decorative Lion, Completed: 1929

Center Plaza, clockwise from top: Central Savings Bank, 115 N. Charles St., Completed: 1891; 201 N. Charles St., Completed: 1967; Fidelity Building, 210 N. Charles St., Completed: 1893; One Charles Center, 100 N. Charles St., Completed: 1962.

Marburg Mansion, 14 W. Mt. Vernon Pl., Completed: 1895.

Clarence M. Mitchell Jr. Courthouse, Entrance Detail, 100 N. Calvert St., Completed: 1900.

10 Light Street, Decorative Eagle, Completed: 1929.

Baltimore City Hall Rotunda, Interior, 100 N. Holliday St., Completed: 1875.

Saints Philip and James Catholic Church, 2801 N. Charles St., Completed: 1930.

Hotel Junker, 22 E. Fayette St., Completed: 1905.

Windows of University Baptist Church, Exterior, 3501 N. Charles St., Completed: 1921.

American Brewery

1701 N. Gay Street

This monument to Baltimore’s brewing history towers over its neighbors on North Gay Street, cutting a strangely dramatic figure above the surrounding rowhouses. Now the home of social services nonprofit Humanim, the American Brewery Building began its reign over this Broadway East hilltop in 1887, when German brewmaster John Frederick Wiessner looked to his homeland for inspiration during the construction of a new building for his J. F. Wiessner & Sons Brewing Co. The architect’s name has been lost to time, but this five-story Victorian behemoth came to be known among locals as the “Germanic Pagoda” and was once the center of a complex that also featured stock cellars, bottling works, and lodging for both the Wiessner family and new arrivals from Germany. After falling into disrepair in the 1970s, the building was the subject of an award-winning adaptive reuse project that ended in in 2009, allowing it to stand for generations to come.

EUTAW PLACE TEMPLE

1305 Eutaw Place

Baltimore architect Joseph Evans Sperry modeled this Bolton Hill landmark—built in 1892—after the Great Synagogue of Florence, Italy. The former home of Temple Oheb Shalom, its carved marble, fortress-like exterior belies a light, spacious interior, while its three clay-tiled domes remain striking to this day against the city skyline as the sun goes down in the evening. The Byzantine structure also stands as a reminder of the vibrant Jewish community that thrived in the city’s growing northwest suburbs at the turn of the century. The Oheb Shalom congregation, originally established in 1853 by young German Jews near Camden Yards, was founded as an alternative religious home for those among the expanding Jewish community who did not wish to attend the older Orthodox Baltimore Hebrew Congregation (1830) or the more radical Reform Har Sinai (1846). Since 1960, it’s been home to the Prince Hall freemasons, whose members included Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall and composer/pianist Eubie Blake. Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke at the Baltimore lodge on behalf of Lyndon Johnson’s presidential election campaign in 1964.

baltimore basilica

409 CATHEDRAL STREET

When Benjamin Henry Latrobe, friend of Thomas Jefferson and architect of the then-new Capitol, volunteered to design the first Roman Catholic cathedral in the U.S. alongside Baltimore Archbishop John Carroll, he went old-school, presenting a European Gothic model. The bishop, however, rejected his initial plans. “The Gothic style has great beauty and spiritual strength,” Carroll explained. “But it speaks to the past. Our cathedral should share the perspective of the new American nation. It will speak to the future in the neo-classic style of the national Capitol in Washington.” And so it did. Built from 1806-1821, the historic basilica emerged as a symbol of the country’s newly won religious freedom. Casting aside darkening stained glass, Latrobe instead built towering, sunlight-welcoming side windows and placed two dozen skylights in the cathedral’s 87-foot main dome—basking the entire sanctuary in restorative warmth and openness. Wilbur Harvey Hunter, former director of the Peale Museum, described the design, ultimately considered Latrobe’s masterpiece, as “a precise and powerful arrangement of form, space, and mass in a manner reminiscent of the best classical architecture, but entirely original as an ensemble.”

“When I look at Baltimore, I see how our past can help us turn a corner.”

orchard street united methodist church

512 Orchard Street

The oldest structure in Baltimore built by the city's black community, Orchard Street Church has survived in its current form for nearly 140 years. In 1839, after hosting prayer meetings at his Baltimore home for 14 years, Truman Pratt, a free black man who had been born into slavery, joined with other free blacks and slaves and erected what would initially be listed as “Orchard Chapel” in a city business directory. By the time Pratt died in 1877, reportedly at the venerable age of 102, the congregation had outgrown its church. In 1882, a new Romanesque Revival-style building, with a mixture of Renaissance-inspired details and a distinctive Gothic window above its doors—later described as the “foremost colored house of worship in the state”—was built at the same location. Through the decades, it served as host to the Colored Maryland Literary Union and reunions of United States Colored Troops. Today, it is home to the Greater Baltimore Urban League.

arch social club

2426 Pennsylvania Avenue

For more than a century, Arch Social Club, one of the oldest continuously operating African-American men’s clubs in the U.S., has been a cornerstone in the city’s black community. Serving as both an entertainment and civic hub over the years, Arch Social hosted top civil rights leaders, including Thurgood Marshall, Charles Hamilton Houston, and Clarence and Juanita Mitchell. Today, with its eye-catching Baroque exterior, it also remains one of the last venues for live entertainment, notably for jazz, on West Baltimore’s historic Pennsylvania Avenue commercial strip. Its current building, acquired in 1972, was originally erected in 1912 as the Schanze Theater, a vaudeville, moving picture, and dance hall venue, before being remade into a banquet hall in the 1950s. In 2018, the Arch Social Club won a national Partners in Preservation: Main Streets grant by popular vote. Those funds will be used to add a state-of-the-art marquee, hopefully setting the stage for the new Pennsylvania Avenue Black Arts & Entertainment District.

THE SENATOR THEATRE

5904 York Road

The marquee at The Senator has listed the titles of hundreds of films, some great, some not so much. But they all seem a little grander surrounded by the neon, glass, and shiny aluminum of this Art Deco movie palace in North Baltimore. The beloved theater has been saved from closure again and again by film acolytes who treasure its throwback looks and independent nature, and it has often been the theater of choice for premieres from local cinema heroes John Waters and Barry Levinson. Its efforts in both architectural restoration and independent film have been honored by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, Entertainment Weekly, and Men’s Journal, among others.