News & Community

Baltimore’s Anonymous "Bike Blaze Guy" Comes Clean

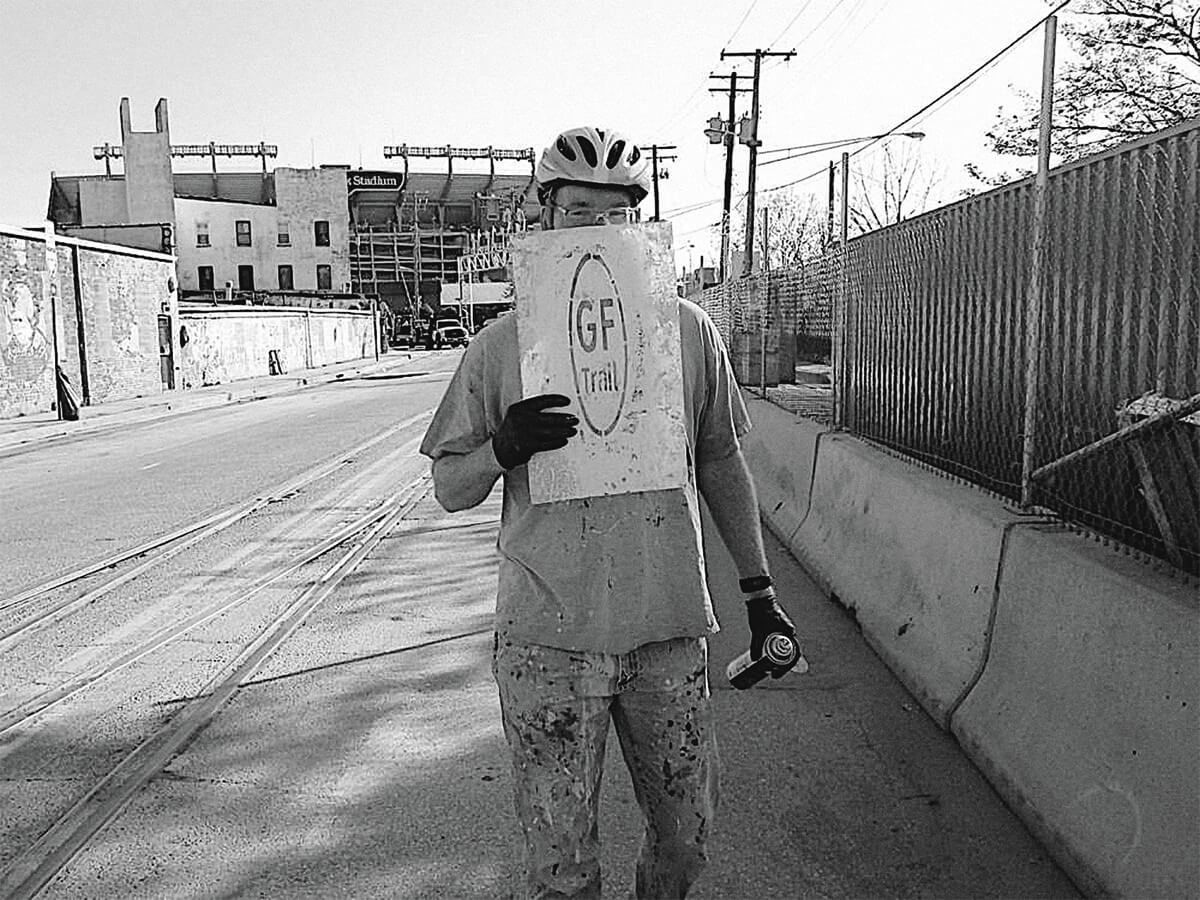

Recently retired, John McDonald has passed his stencils off to a team of bicycle advocates.

The first time John McDonald rode the Gwynns Falls Trail, he lost his way. The second, third, fourth, and fifth try, too. Only on his sixth attempt did he finally navigate the full length of the city’s glorious, if complicated, 15-mile urban bike trail.

Completed in 1998, the Gwynns Falls path stretches from Federal Hill to Middle Branch Park in South Baltimore, through Pigtown to the Dickeyville Historic District, and all the way out along the stream valley where it gets its name to the open meadows and Piedmont forest at the far western edges of the city.

The unique greenway connects no less than 10 parks, 32 neighborhoods, and 31 historical sites, interpretative panels included. It’s a treasure, if originally a hidden one.

“Each time I started riding, I’d gradually realize I’d wandered off the trail and have to get back on track,” says McDonald, a lifelong cyclist and now retired college professor. “I thought it was great, I just didn’t think it should be so difficult to follow. I didn’t want to keep stopping every few minutes to pull out a map because that’s not fun. It needed signage.”

Like any conscientious citizen, McDonald initially approached the city, specifically former Baltimore bike and pedestrian coordinator Nate Evans, about a solution.

“That was 2012, when the city budget for bicycle infrastructure was probably $500,000—less than $1 a resident,” McDonald recalls. “Nate kind of laughed. There just wasn’t money for any more traditional metal sign posts.”

Then, inspiration struck. McDonald’s father had been an Appalachian Trail volunteer in North Carolina and helped paint the iconic trail’s white blazes. If markers on trees worked for hiking trails—why not road-blazes for bicycle trails?

He pitched Evans again, who told him spray painting “blazes” on city-owned streets wasn’t in compliance with federal transportation guidelines and Baltimore DOT wouldn’t go for it. Essentially, it was illegal, Evans said, adding, however, it was a great idea and if asked, he’d deny he had ever heard anything about it—wink-wink. “That’s when I became ‘Bike Blaze Guy,’” McDonald says.

Over the next seven years, McDonald loaded his beat-up, 1982 Fuji 12-speed and bike rack with cans of spray paint and stencils. He marked out 500-plus green blazes—before and after each turn—on the Gwynns Falls Trail, 300 more on the Jones Falls Trail, and another 100 blazes for good measure on the shorter Middle Branch Trail. All done anonymously, on his own dime. All requiring semi-annual repainting.

There were occasional hiccups. A troublesome Federal Hill resident inexplicably barked at him for defacing a pot-holed and glass-strewn street. And there was a pair of run-ins with police, who decided the bespectacled, unassuming professor in the paint-splattered jeans wasn’t worth hassling.

But clearly McDonald is not easily dissuaded when he sets his mind to task, and the simple gratitude of local bicyclists who stumbled upon him at work proved more than enough to sustain him. (The photo above was taken by one such bicyclist.) Later, people at Rec and Parks and Bikemore, the local nonprofit, came to know him and kept his identity a secret.

In fact, it was not until retiring from the University of Delaware in 2019 and deciding to move to Washington state that the 62-year-old McDonald “outed” himself at a Bikemore-thrown going-away party at Peabody Heights Brewery. The hope was that a crew of volunteers could be recruited pick up where he left off.

Today, Eleni Giorgos, a 31-year-old mom who started bicycling in the city as a student at MICA, coordinates a team of 14 “blazers.” Rec and Parks even buys the paint these days.

McDonald, meanwhile, has resumed tackling the kind of long-distance rides he’s loved for decades. Figuring out the logistics has always been part of the fun, too—even if, as with the bike blazes, he sometimes bites off more than he probably should.

“I finally did a cross-country trip in 2015, Portland to Baltimore,” he says. “Forty-seven days, averaging 87 miles a day. When I reached Ohio, I was ready for it to be finished. You know when you travel and there are little things from home they don’t have? And when you start seeing them again, you know you’re almost home? When I got to West Virginia, I stopped in a convenience store and saw a bag of Utz potato chips on the shelf. Best bag of potato chips I ever had. After that, I was like, ‘I can do this.’”