This story was produced in partnership with the Garrison Project, an independent, nonpartisan organization addressing the crisis of mass incarceration and policing. Explore more of the project’s coverage, here.

Around 10:30 a.m. on May 22, 2020, 60-year-old Steven Lamont Clark Sr. was shot and killed in front of his home in West Baltimore’s generally quiet Forest Park neighborhood.

The crime scene on the 4200 block of Norfolk Avenue was small—a pool of Clark’s blood, three .40 caliber bullet casings, and a baseball cap on the ground.

The Baltimore Police Department homicide detectives who canvassed the area wrote in their report that they were told by eyewitnesses, including one of Clark’s brothers, that the shooter “entered a blue pickup-style truck,” after the murder.

Clark’s family also told detectives that days before the murder, Clark’s oldest son had gotten into some type of “beef” and physical altercation with a person they suspected of the shooting. They believed Clark was killed in retaliation for the fight involving his son. “He’s in the streets,” Clark’s sister Denise said of her nephew in an interview with local news affiliate Fox45.

The week of Memorial Day, 11 people were murdered, including Clark. There were 39 murders that month, and the year ended with 335 slain. It was the sixth straight year of 300-plus homicides.

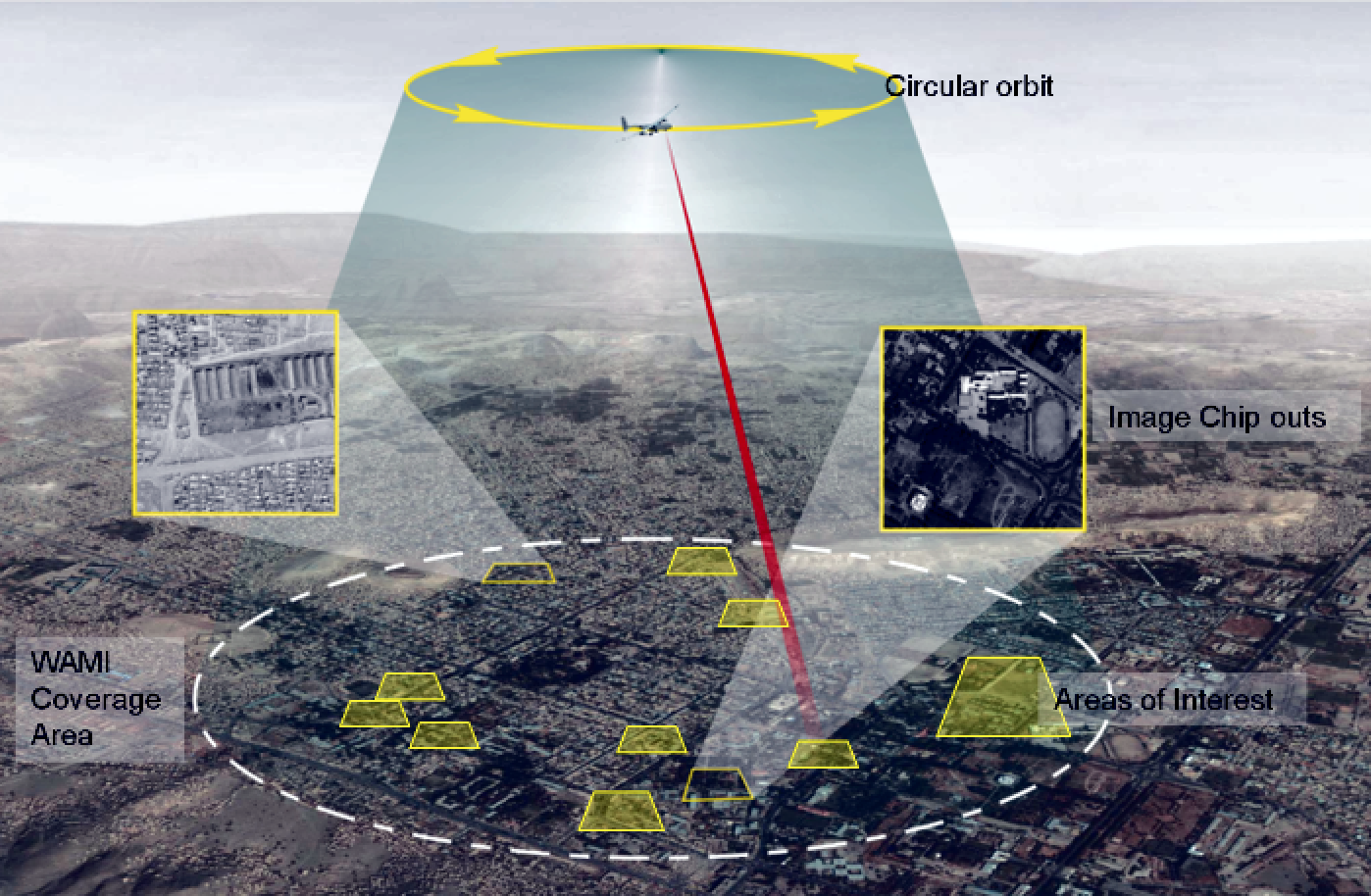

Coincidentally, less than a month before Clark’s murder, two citywide surveillance planes—equipped with state-of-the-art video cameras—were relaunched over Baltimore as part of a six-month pilot program by the police department. The daytime shooting was exactly the kind of violent crime that a dozen, 192-megapixel cameras attached to a plane circling West Baltimore were supposed to help police solve.

The “spy plane”—as Baltimoreans coined the single-engine Cessna—had flown once before. Throughout 2016, it was operated by Persistent Surveillance Systems, a private company, in an arrangement with the BPD in what was called the “Community Support Program.” The plane was operated by military technologist Ross McNutt and funded by Texas billionaires John and Laura Arnold, who run Arnold Ventures, a philanthropic organization whose focus areas include the criminal legal system.

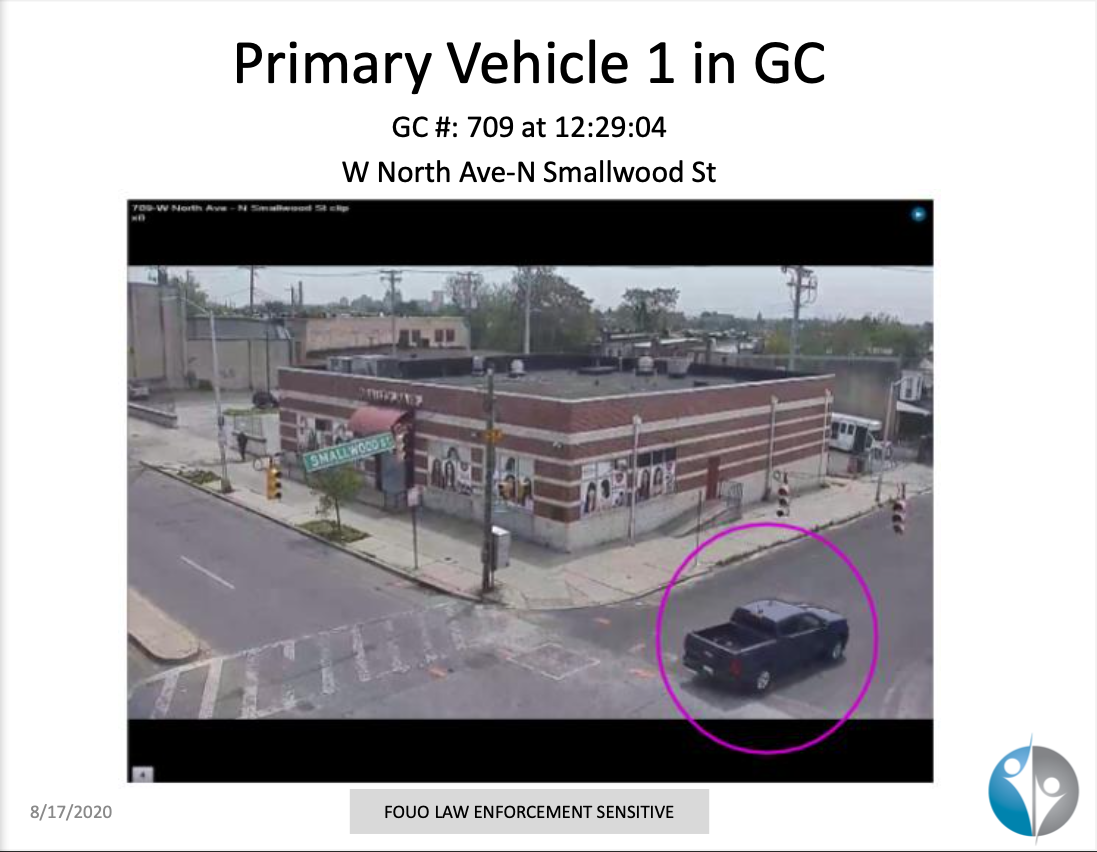

The plane circled over the city at roughly 5,000-10,000 feet, and took one photo every second, capturing about 30 square miles of the city at a time. After a crime occurred, analysts rewound and fast-forwarded its footage and reported their findings to police. Detectives and analysts cross-referenced the plane’s findings with Baltimore’s public and private on-the-ground security cameras, which can capture a face or license plate number.

But the initial 2016 spy plane program had not been disclosed to the public. Baltimore residents and elected officials only learned of it thanks to an August 2016 Bloomberg Businessweek story exposing its deployment. Baltimoreans were outraged that they were secretly surveilled by a plane and learned of it in the news.

“The secrecy of the program has precluded any oversight of the technology’s use,” the Maryland Office of the Public Defender said after the plane and its purpose were revealed. “Widespread surveillance violates every citizen’s right to privacy; the lack of disclosure about this practice and the video that has been captured further violates the rights of our clients who may have evidence supporting their innocence that is kept secret.”

Nonetheless, after Businessweek revealed its existence, the plane was not prohibited from flying, even though its flights were not particularly effective in solving violent crime. Instead, it went through a reform process. McNutt, the plane’s inventor, pitched community organizers, church leaders, and mothers of gun violence victims on a rebranding of the plane. “This is not a law enforcement tool,” he told residents. “This is community assistance.”

There were public hearings and a Memorandum Of Understanding (MOU) between the city and Persistent Surveillance Systems. The MOU ensured that the plane’s flights in 2020 would be disclosed to residents, its data properly stored, and that it would only be used to investigate murders, shootings, armed robberies, and carjackings. Researchers would also observe its use and organizations such as the Policing Project of New York University would produce an audit (co-author and Williams College professor Benjamin H. Snyder, author of the forthcoming book, Spy Plane: Inside Baltimore’s Surveillance Experiment, was a researcher observing the plane).

Ultimately, the Baltimore Police Department’s daily, overhead surveillance of its citizenry was ruled unconstitutional a year after its second experimental run. So how, and why, did the City State’s Attorney’s Office incarcerate a West Baltimore man named Terrence Carter for three years in the Clark murder case with dubious evidence linked to the use of the illegal spy plane?

Detective Tavon McCoy turned to the Community Support Program for help in solving the murder of Steven Clark Sr. But the plane was not flying when Clark was killed. It cannot operate in inclement weather and it was raining that morning.

However, in the days after the murder, police had put out a BOLO—an acronym for “be on the lookout”—for the blue pickup truck seen leaving the Clark crime scene. A Baltimore police detective, working as supplemental security at Mondawmin Mall on May 19, told detectives he interacted with two men in a blue pickup truck. Police pulled security footage from outside of the mall, which showed the truck in its parking lot.

McCoy wanted to track the truck on that day using the plane, hoping it could help identify its occupants and their whereabouts. He put in a “supplemental request”—a workaround included in the MOU to enhance the scope of the plane’s surveillance—and subject to approval by then-Baltimore Police Commissioner Michael Harrison.

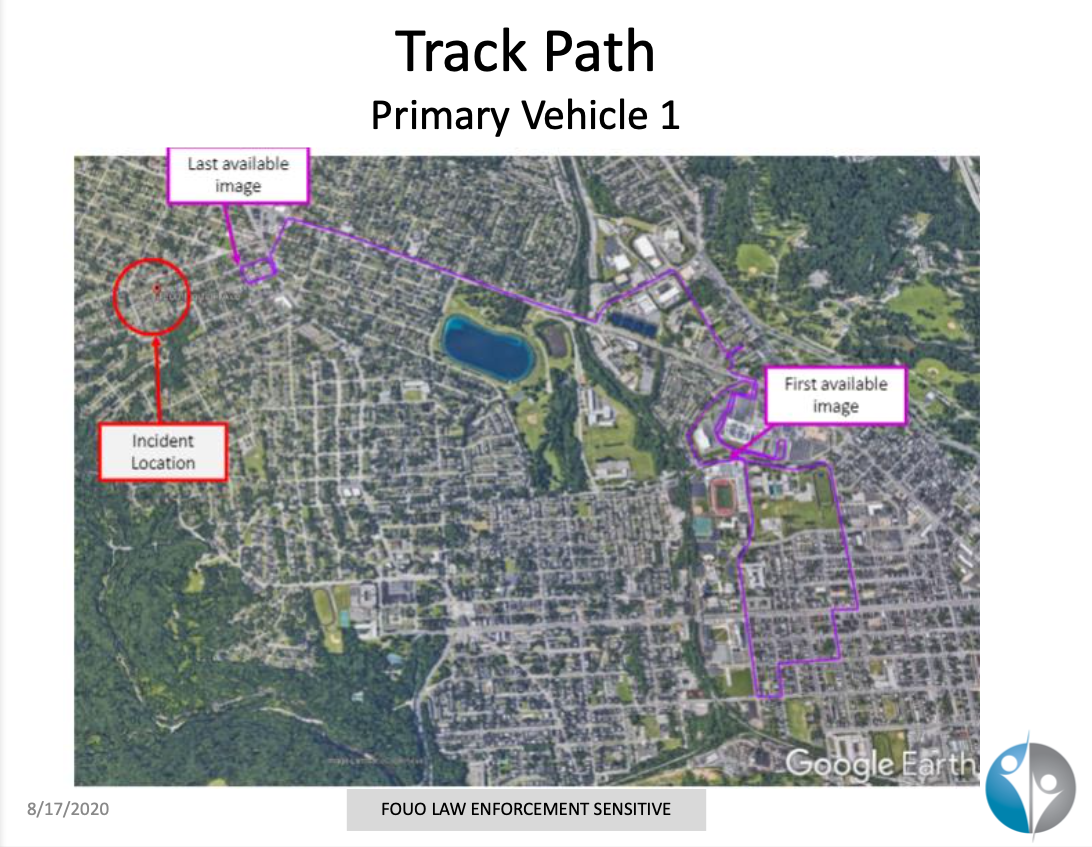

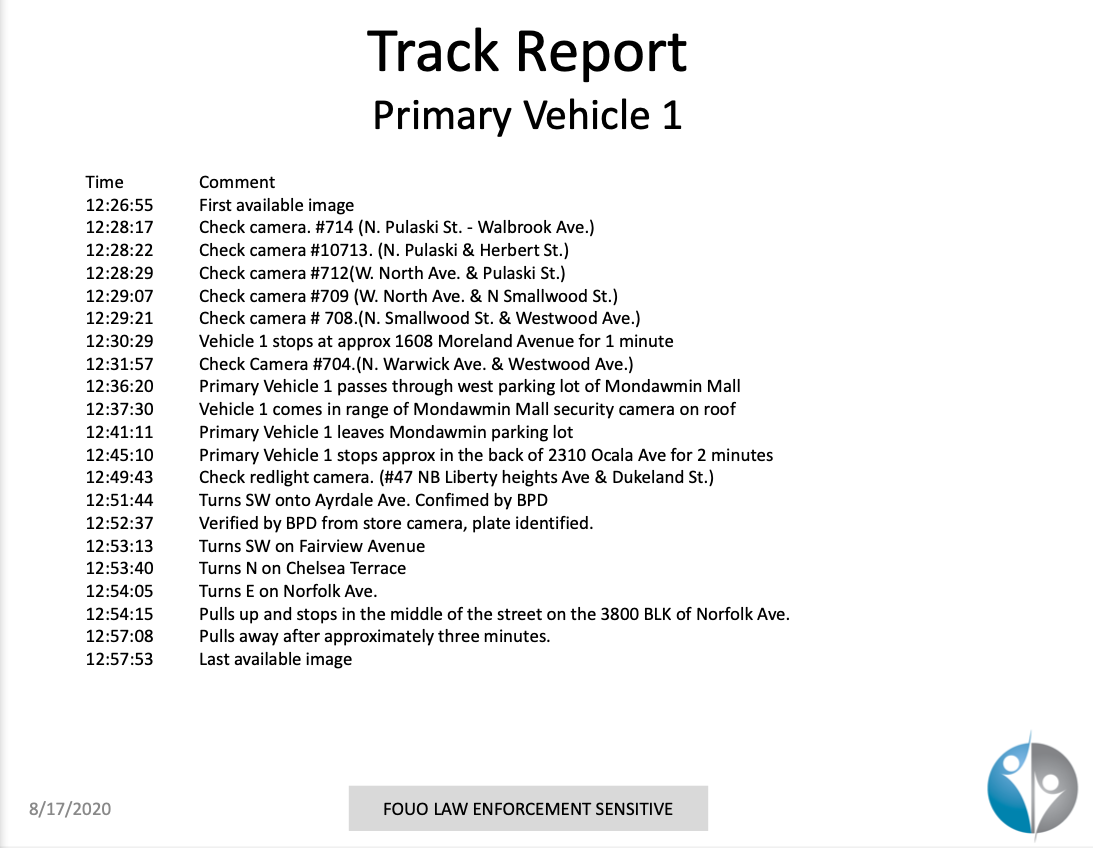

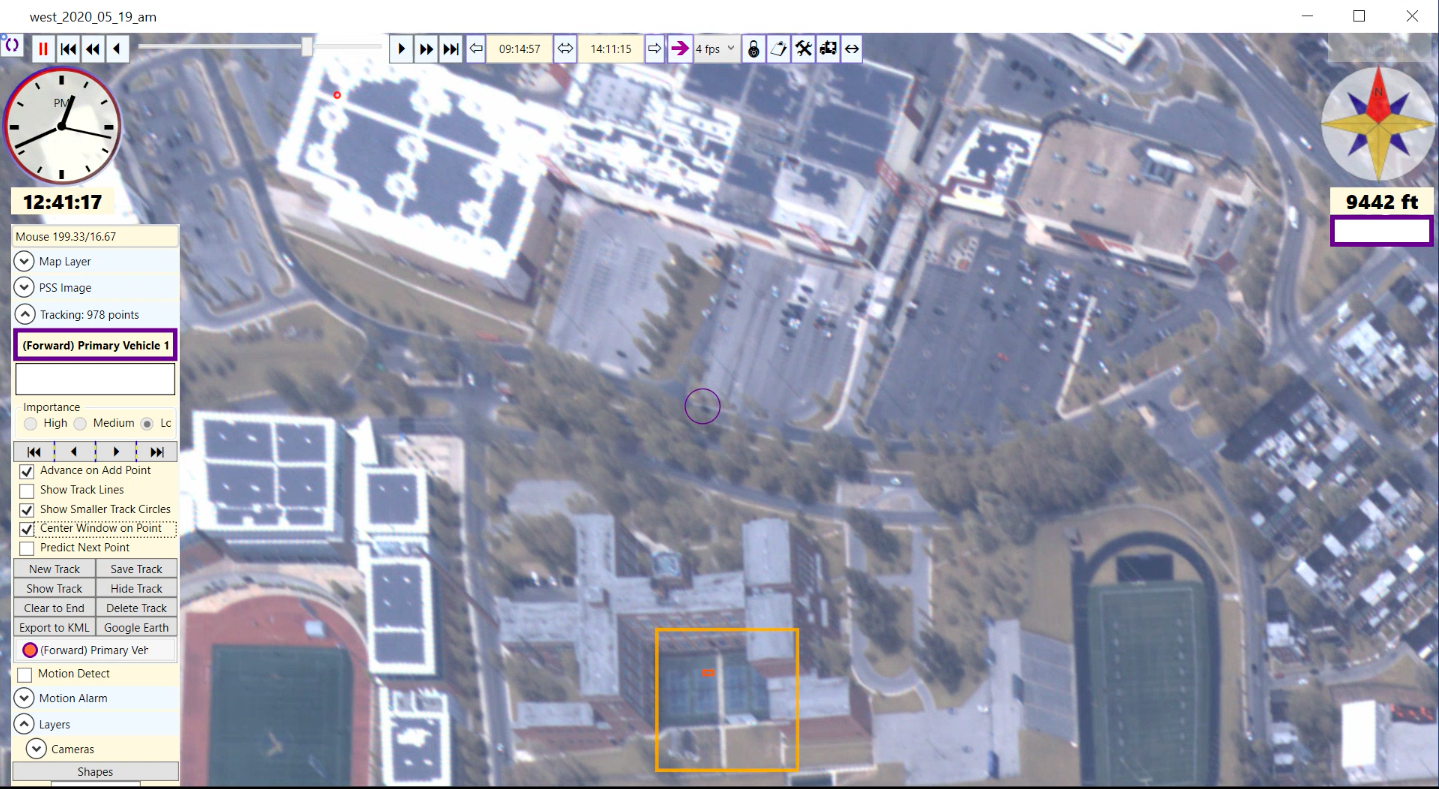

On May 26, 2020, Community Support Program analysts and homicide detective Evan Zimrin reviewed the plane’s footage at the mall for May 19, three days prior to Clark’s killing, searching for a then-unnamed murder suspect in a blue truck.

From an office downtown, analysts pulled up the plane interface—a low-res overhead view of the city moving at a rate of one frame per second—and tracked the truck to and from Mondawmin Mall. They observed the pickup driving around town and highlighted locations where it had stopped.

At some point, analysts lost the truck on a road covered by trees. At another point, one of the plane’s wheels blocked the cameras entirely and the vehicle’s route was lost again.

Separately, another analyst used the locations pulled from the plane footage to locate the truck in the city’s on-ground CCTV surveillance-camera footage. In some of the footage, parts of the license plate number were clear. With the make, model, and color of the truck and one or two license plate numbers visible, detectives easily identified the vehicle and its owner—Enterprise Rent-A-Car.

Baltimore homicide Detective Marcus Sanders had also gathered a significant amount of ground security footage from the day of the murder. He pulled security camera video from nearby apartment buildings and a gas station that showed the truck near the scene of Clark’s murder before and after it occurred. Sanders also learned the truck was returned to an Enterprise Rent-A-Car location around 3 p.m. on the day of the shooting, despite being rented through May 25.

The Community Support Program prepared a report on its findings. The plane’s investigative summary noted that on May 19, the truck stopped at a location “associated with the person of interest” in Clark’s murder three blocks away from the site of the murder. The report also noted that the location where the truck was last seen before the plane wheel blocked the frame was near the site of the murder.

But using the plane’s surveillance footage to look at an alleged suspect’s routine in the days prior to an alleged crime violated the plane’s MOU.

The MOU says supplemental requests should only be used in “extraordinary or exigent circumstances” such as a child abduction. In the Clark murder investigation, the plane was used to surveil a vehicle merely associated with the suspect days before the crime and miles away from the crime scene.

Still, McCoy’s supplemental request to surveil the truck days before the murder was approved by Commissioner Harrison. The NYU Policing Project’s audit of the surveillance plane published in December 2020 criticized the BPD’s use of supplemental requests. They said this use of the plane gave police too much unchecked leeway to track citizens.

David Rocah, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU Maryland, told Baltimore magazine and The Garrison Project that he wasn’t surprised the plane was used for purposes beyond what officials promised.

“When the spy plane was being used in secret, when it wasn’t disclosed, they said, ‘Well, it was only for murders,” but Rocah explained, it turned out it was used for many other crimes including low-level crimes such as illegal dumping. Then in 2020, Rocah added, the plane operators and the city enacted a “highly scrutinized, supposedly highly restricted pilot program in public” and went on to violate the MOU. “They cannot tell the truth,” he said.

Police believed that the person who killed Clark was Terrence Carter. In charging documents, detectives did not explain—or provide the basis for—their belief that Carter, then 32 years old, murdered Clark. They did not mention use of the surveillance plane, but instead asserted that they “obtained” unspecified information, from, among others, an “anonymous source,” that led them to believe Carter was responsible. Detectives said cell-tower site data showed that Carter was in the general vicinity of the homicide as well. Det. Sanders also obtained outside security footage of Clark’s son’s home, which showed someone entering his apartment and then leaving hours later, seemingly limping, as if he’d been in a fight. Police believed this man was Carter.

On July 9, 2020, Carter was arrested. According to documents obtained by Baltimore magazine and The Garrison Project, the Community Support Program (CSP) took credit for Carter’s arrest. The investigation summary for the case begins with the following claim: “BPD’s collaboration with CSP resulted in the discovery of Usable Surveillance Evidence supporting case closure that, to our knowledge, would not otherwise have been possible without CSP’s contribution.”

Det. McCoy only referenced “video evidence” in the charging documents, not all of its various sources, and wrote that “witnesses” had “positively identified” Carter as the driver of the blue truck on the day of the murder. “Information was obtained by detectives that there was an altercation between Terrence Carter and Mr. Clark Sr.’s son on or about May 19, 2020,” according to the documents. “Video evidence was obtained showing the vehicle fleeing the scene of the shooting.”

But no witnesses had positively identified Carter that morning, it would later be learned. In fact, there was no video—from the plane or on-the-ground security footage—showing a blue truck leaving the crime scene.

The Baltimore City State’s Attorney’s Office charged Carter with first-degree murder, use of a firearm in a violent crime, and possession of a firearm with a felony conviction. Carter was held without bond.

In May 2021, almost a year after his arrest and incarceration, Carter was offered a plea deal of 60 years with five years of probation, which he rejected. He chose instead to go to trial, and would spend another year and a half in jail awaiting trial even as The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, ruled the following month, in June 2021, that the plane’s 2020 flights were unconstitutional.

The decision stemmed from an April 2020 lawsuit brought by the ACLU on behalf of three parties: Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, a Black-led, Baltimore-based grassroots think tank; Erricka Bridgeford, co-founder of the Baltimore Ceasefire 365 project; and Kevin James, a community organizer and rapper. The ACLU had argued in its suit that the plane “will put virtually all Baltimore residents under constant, aerial surveillance” and violates their First and Fourth Amendment rights.

In the wake of the ruling, prosecutors quietly dismissed most criminal cases that used the plane to gather evidence.

A separate 2020 murder case that used information from the plane was dropped weeks before trial because of the plane’s constitutional issues. The Carter case proceeded, however.

“As a technical legal matter, prosecutors needed to take the ruling into account and they certainly would have been operating ethically and correctly to drop cases in the wake of that decision,” Rocah said. “In my view, there’s no plausible legal argument for them to make [the case] that, despite the Fourth Circuit decision, it wasn’t illegal.”

Carissa Byrne-Hessick, a criminal law professor at the University of North Carolina and author of Punishment Without Trial: Why Plea Bargaining Is A Bad Deal, said the Fourth Circuit ruling should have ended the case against Carter. “If a court told the government that it is unconstitutional for them to have been using this plane, that doesn’t just mean that they can’t use the images shot by the plane,” Byrne-Hessick said. “It also means they can’t use evidence” the plane led investigators to.

On October 24, 2022, the day of Carter’s trial—more than two years after his arrest—a jury was selected and prepared to be sworn in. But then the State’s Attorney’s Office dropped the case. The decision had nothing to do with the plane—its use had still not been revealed to Carter or his attorney—the case had simply dragged on during the COVID-19 pandemic and stood a good chance of being found to have violated Carter’s speedy trial rights, the State’s Attorney’s Office said later.

Prosecutors also said they’d lost one of their witnesses—Clark’s brother died on September 22, 2022—and that they needed more time to locate others.

Shortly after Carter was released from jail, the State’s Attorney’s Office re-indicted Carter on November 18, 2022. He would remain on house arrest until his 2023 trial.

Byrne-Hessick said that while police and prosecutors “didn’t have control over whether a witness died or not,” there wasn’t much done before filing charges again—and bringing charges against someone a second time is rare.

According to James Bentley, the current director of communications for the Baltimore State’s Attorney’s Office, the decision to move forward with the case was made “after consulting the victim’s family” and because police located a new witness. “Due to the close proximity of the trial, we dismissed the case and re-indicted it only after investigating this new information,” Bentley said.

That new witness was Michael Clark, a brother of the victim, who lived nearby. According to police, he said that he heard an argument between his brother, Steven, and the shooter, then heard gunshots, and saw the blue truck driving away.

This past August, the case against Carter finally went to trial. He had been incarcerated for 26 months and then detained on house arrest for nearly another full year.

As expected, Bradley MacFee, Carter’s defense attorney, filed a motion arguing that his client’s right to a speedy trial had been violated and the charges should be dropped. Baltimore District Court Judge Charles Peters determined, however, that the State’s Attorney’s Office had “acted in good faith” when they dismissed the charges. They’d lost one witness to death. Another witness—the man who actually rented the blue truck from Enterprise and police said, had loaned it to Carter—evaded detectives and could no longer be found. Peters acknowledged that re-indicting someone after dropping the charges is “not done frequently.”

“It’s kind of surprising that this case went to trial,” Byrne-Hessick said. “Most cases don’t go to trial.” Byrne-Hessick also explained that limited resources by police and prosecutors means that there were “other cases that they didn’t fully investigate and prosecute because they were working on this case.”

McCoy, identified as the primary detective on the case, did not testify at Carter’s trial. McCoy was among those included on former State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby’s “do not call” list, a publicly available list of police officers who have been deemed untrustworthy or not credible in court. In 2019, McCoy was accused of lying to the girlfriend of a murder suspect, interviewing her for 12 hours after she demanded a lawyer. McCoy’s involvement in the case was not disclosed to the jury in Carter’s case.

Evan Zimrin, the homicide detective who worked on the surveillance plane part of this investigation, also did not testify.

At one point during a motion hearing in front of the judge, Det. Sanders, who was also on Mosby’s do-not-call list, claimed one of the witnesses could make a positive identification of the shooter. “I can’t recall whether [the witness] was testifying to the person he saw shooting, but I believe he was present during the shooting,” Sanders said on the stand.

Amy Brown, a prosecutor with the State’s Attorney’s Office, corrected Sanders, noting that no witness saw the shooter.

During the trial, Sanders also took the stand, to answer questions about his investigation and the on-the-ground surveillance footage he obtained. According to Sanders, the truck was rented by a man investigators said knew Carter. There were calls and text messages between Carter and this man. Police claimed cell-phone tower data showed Carter near the scene of the murder and driving away from it.

MacFee argued that Carter lived less than two miles from the location where Clark was killed and that cell-phone tower data simply put Carter’s phone “in the general area” around the time of the shooting.

Additionally, prosecutors argued that Carter was in a fight with Clark’s son. He went to the emergency room on May 19.

MacFee stressed to the judge and jury that there had been no positive identification of Carter in any of the on-the-ground security footage. The footage showed a blue truck rented out by someone Det. Sanders said knew Carter, with whom Carter communicated, near the scene of the crime and before and after the crime. None of the witnesses presented, however, identified its driver.

“There was no post-arrest investigation done in this investigation at all, which is why we have nothing,” MacFee said to the jury. “Despite not being the lead detective but the only one that we have the opportunity to meet with during this case, Det. Sanders testified that he has no idea who was in that truck on the morning of May 22, 2020 when Clark was killed, or how many people were in that truck.”

“This is a circumstantial case,” Assistant State’s Attorney Brown explained to the jury. She insisted, nonetheless, that all of the security camera footage, along with cell-phone data that placed Carter near the murder scene, were “more than enough to infer” his guilt.

On August 23, Judge John A. Howard sequestered the jury and for about half an hour, reviewed footage from the gas station and apartment complex, as well as footage of a man leaving the home of Clark’s son with a limp. He concluded that the case should not go to the jury and that there had been “no identification” of Carter.

“The state has presented a case in which there has been no identification by direct testimony or anything that would corroborate testimony—DNA, fingerprints, anything of the like—that Terrence Carter was the person who killed Steven Clark on May 22, 2020,” Howard said. “The state, with limited resources, has presented to the court a very interesting series of unfortunately unconnected events.”

Howard then dismissed the case—permanently this time. “Taking all of those pieces together and in spite of a relatively herculean effort by Ms. Brown,” Howard said, “the court is persuaded that the evidence is not sufficient to establish the guilt of the defendant.”

MacFee said he did not know the surveillance plane was used in his client’s case until he was contacted for an interview by Baltimore magazine and The Garrison Project for this story.

“If you use it without a warrant, it very possibly becomes a suppression issue,” he said. “If I had learned the means by which they determined certain aspects of the case, I would’ve moved to suppress the identification of the vehicle and I believe it would’ve put an end to the case at that stage.” MacFee said he “might have even used [the existence of the plane] in a bail review hearing. ‘Hey, look Judge, let the guy go because half their case they are not going to be able to use.’”

For Carter, it had been a three-year ordeal, much of it spent incarcerated. Carter spent more than two years in jail and nearly one more on home detention waiting for the State’s Attorney’s Office to prepare for trial. MacFee called it “oppressive pre-trial incarceration.” During this period, Carter lost his job and could not see his daughter. While on home detention, he was not allowed to look for work. Clark’s family, meanwhile, never got justice for their loved one.

“There are all kinds of collateral consequences when somebody sits in jail. People lose jobs, people lose houses, bills get behind, relationships go bad,” MacFee said. “The collateral damage is considerable. This dragged-on for three years. You know, that’s time that [Carter] will never get back.”

In response to Baltimore magazine and The Garrison Project’s request for comment, Bentley of the State’s Attorney’s Office said, “Based on our investigation, the State did not use any spy plane information to establish its case. It is our understanding that the Detectives found the spy plane footage from days before the incident unhelpful because they already had the information from other sources.”

MacFee believes that the use of the plane should have been disclosed by the state. “You can’t surreptitiously go around using this technology that is not to be used either at all or without a warrant,” MacFee said. “If they did use that plane to investigate any part of that case, even if they don’t use it at trial, it’s still a tool that you’re not able to use absent a warrant.”

For Byrne-Hessick, the use of the surveillance plane without disclosing it is only one of the issues with the case.

That Carter was taken all the way to trial only to be dismissed by a judge due to a lack of evidence is concerning: “This seems to be an awfully weak case to take to trial—and this really messed up this guy’s life. Not much evidence and you have a judge that dismissed it. What went wrong here?”

Former City Paper editor-in-chief Brandon Soderberg reports on cops, guns, and drugs. He is the co-author of the book, I Got a Monster: The Rise and Fall of America’s Most Corrupt Police Squad.

Benjamin H. Snyder is the author of Spy Plane: Inside Baltimore’s Surveillance Experiment (2024 UC Press) and his work centers around surveillance, tech, labor, and inequality. He teaches sociology at Williams College.