There are so many places you could start a story about Yahu Blackwell.

He’s 33 years old, and has already lived a life worthy of novel. He’s a former police officer, who was also arrested as a teenager. He’s a professional boxer, and his next fight is Saturday at a hotel in Rosarita Beach, Mexico. He’s a businessman, too. For the last year, he’s been preparing to open Baltimore’s newest Rita’s Italian Ice location in the Rotunda courtyard in Hampden. “A new sink is going in today,” he recently told us by phone.

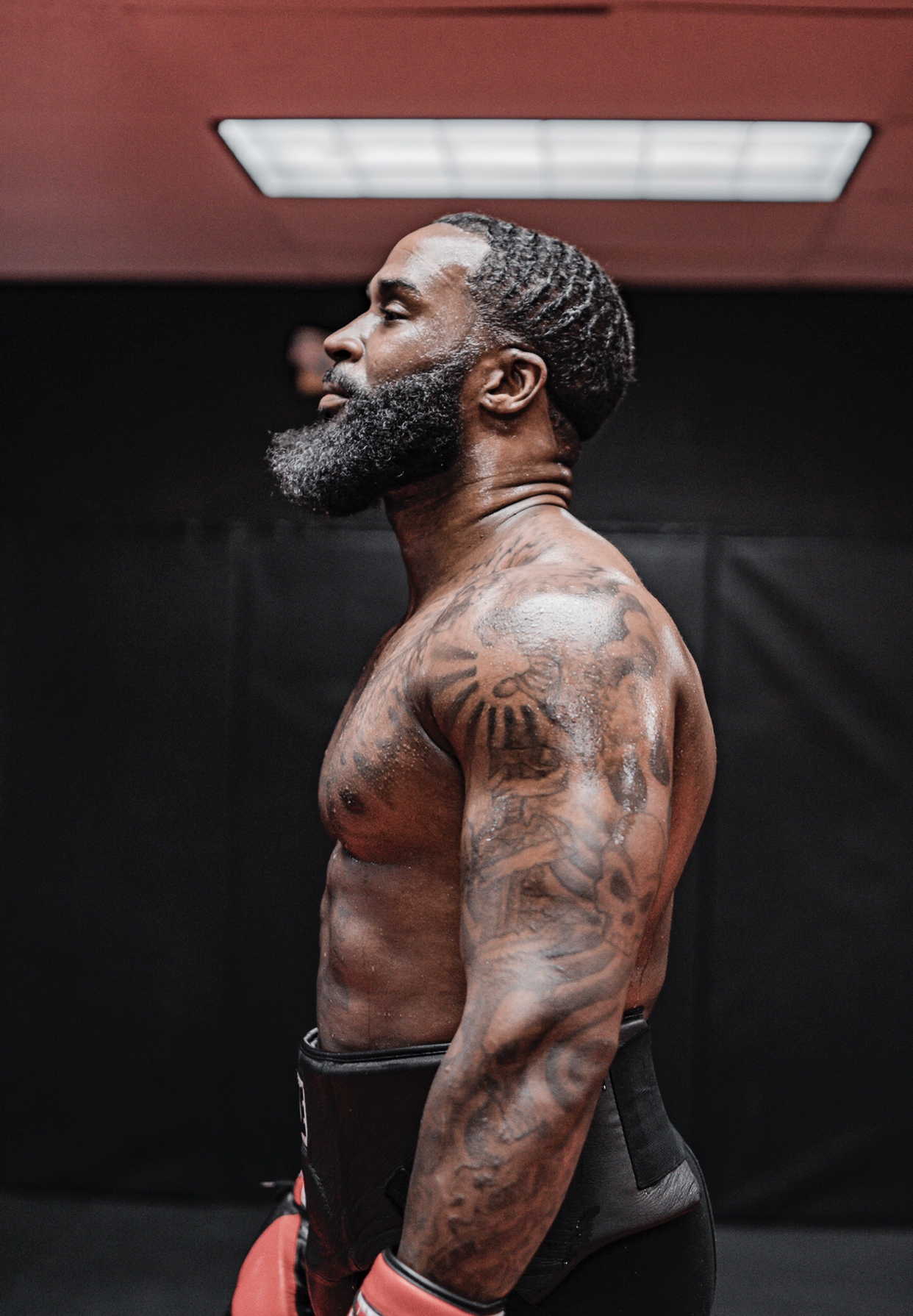

Of Nigerian descent and Jewish faith, Blackwell’s first name, Yahu, appropriately means “everything” in Hebrew. He is busy. One look at his Instagram account can give you a great glimpse of it. There are videos of the 5-foot-10, 200-pound-ish fighter at work, and the bio at the top of his page reads: “King From the Akan People | Hebrew Blooded | Pro Boxer.”

And everything this local hero living in Owings Mills has worked for until this point seems to be aligning as planned right now. “I know that sounds cliché, but I tell kids all the time, ‘If you put your mind to it, you can really do it,’” he says. “I’m proof.”

Blackwell didn’t go to college and has no formal business education. But, as he told Forbes a few years ago, his goal is “to become the richest athlete from Baltimore.” And after going 156-28 as an amateur boxer, becoming the World Boxing Union novice world champion, and starting 15-0 as a pro cruiserweight in the International Boxing League over the last decade—he still plans to fight for at least another five years—Blackwell’s out-of-ring pursuits are just getting going. The Rita’s grand opening, a few years in the making, is approaching, and he has eyes on real estate projects in the area where he grew up.

That’s really where his story begins. He’s a product of the relatively low-income Lansdowne and Edmondson neighborhoods in south and west Baltimore, and the son of the late Sandra Blackwell, a doting mom and hospital worker, and father, Dwayne, who’s been out of the picture for most of his life. “A typical Baltimore story,” Blackwell says of his dad. “Got caught up selling drugs, ended up getting hooked on drugs, and he’s been fighting those demons his whole life.”

Another male influence, a neighbor and Baltimore County police officer, Rodney Kenion, introduced Blackwell to boxing. He secretly trained at Mack Lewis Boxing Gym in East Baltimore without his mother’s knowledge until he came home with a tournament-winning trophy as a teenager. Mom tried to dissuade him from the violent pursuit, at one point even telling his coaches to give him an extra beating one day at the gym. They did. It didn’t work. “She picked me up in the car afterward and said, ‘See, you don’t want to do that?” Blackwell recalls. “I was like, ‘No, I want to go back.” It was an outlet.

Almost five years later, while riding in a car with friends who were carrying guns, an 18-year-old Blackwell was face down and handcuffed in the street, he says, with another officer holding a gun to his head.

“I was just sitting in the backseat, and we get stopped, and they take us out the car, make us sit on the sidewalk, you know how that goes,” he says. “That was the wake-up call for me. It was such a bad experience. I remember I was laying in my cell, and I told God, ‘If you get me out of this. I’ll be the person that you want me to be.’”

A prescient Baltimore County judge, Ruth Jakubowski, let Blackwell go and expunged his record after hearing his lawyer’s arguments about him being a good kid in a bad neighborhood. “I believe you’re going to make your mark in the world,” he recalls her saying. “But don’t make a fool out of me and come back here.” He did go back, but not how the judge expected.

After Blackwell was arrested, he followed Kenion’s path again, at his mom’s suggestion. Blackwell became a cop himself, putting him on both sides of the renewed, ongoing national debate about policing in America.

“The police needs to be a part of the community,” he says. “And not a thing that’s feared by the community. When I was arrested, I thought they were going to kill me.”

Two years into his police career, Blackwell—who was boxing as an amateur while trying to get signed by an agent—had another chance encounter. This time it was with a local businessman, Josh Dreiband, the vice president of the Northwest BMW car dealer. He had seen Blackwell sparring at the Ferocity MMA gym in Northwest Baltimore where they both worked out. One morning, Dreiband had accidently left money out in the open in the locker room. Blackwell saw it, but didn’t take it. Instead, he struck up a relationship with Dreiband, who eventually offered him a $250,000 signing bonus and the promise of representation.

For a lot of people, that would be that. But around that time, Blackwell read a Sports Illustrated article that estimated 60 percent of former NBA players are broke within five years of retirement, and later he was watching a documentary that focused on the high percentage of professional athletes that blow all their money.

“I was like, ‘these are guys making $30-, $40-, $50-million contracts, what do you mean they’re broke?’” he says. “It was because they didn’t make any investments. They were living off their talent, but eventually that comes to an end. I knew that I need to also be skilled in this area as well if I want longevity.”

As he started to make between $30,000 and $50,000 per fight along with about $20,000 annually in endorsements, Blackwell started saving money with eyes on starting his own business. He was reading about successful pro athletes-turned-entrepreneurs, like Shaquille O’Neal and his dozens of Five Guys burger joints and Krispy Kreme donut shops. Family and friends suggested Blackwell start a trucking business.

“I was just saving, saving, saving. I would pay my bills, put a little money to the side, my fun money, go out to eat, go to movies, then I would just save everything,” he says. “Then I was just trying to figure out how I was going to invest my money.”

Three years ago he got his answer in unfortunate circumstances. His mother got pneumonia and Blackwell says doctors in a local emergency room performed a surgical procedure on her lung that they shouldn’t have, leaving her struggling to breathe and eventually with heart failure (and a malpractice suit pending). As his mom became weaker and weaker, she asked for one her favorite foods, a chilled Italian ice. She passed away on July 5, 2015 at the age of 50. “When the situation happened with my mom,” Blackwell says, “that’s what solidified Rita’s.”

For about the last month, Blackwell has been maneuvering through the social-distancing era and putting the finishing touches on the Rita’s kiosk at the Rotunda that will open soon. (The signage just went up this week.) And he’s also been training for his next fight, as usual. The day typically starts with a two-mile run in the morning if the weather is good, 10 trips up a 300-flight concrete outdoor staircase in Timonium, followed by a mile run and boxing at a private gym.

“It hasn’t really bothered me much,” he says of the pandemic and stay-at-home rules, “because I’m always trying to find something productive to do anyway.”

It’s not hyperbole: Yahu is everything, and then some.