Students typically enter the Center for Military History at The Boys’ Latin School of Maryland through a door inside of its Upper School. But for visitors who use the proper exterior entrance and bound up the stairs—the first thing they see is a sectioned off area honoring one of the school’s own.

The late Marine Cpl. Nicholas Ziolkowski was a well-liked student athlete who enlisted after graduating from Boys’ Latin in 2001. Sadly, he passed away in 2004 while fighting in Iraq. Museum curator and longtime military history teacher Butch Maisel—who has taught at Boys’ Latin for nearly 40 years—lights up when he talks about him.

“Nick’s mother was the first to see the exhibit,” Maisel mentions while explaining Ziolkowski’s memorial, which houses his boots, as well as other personal belongings. “This helps us understand why we do what we do.”

To be fair, Maisel lights up talking about everything and everyone in the museum. But Ziolkowski is an important representation of what the space is all about—providing students with real world, personal accounts of those who have served our country in periods stretching from the Revolutionary War to the War on Terror.

“Our goal is to help the boys develop a vision for themselves that’s greater than who they are and understand what it means to be a man who lives out the values of courage and integrity and passion,” says headmaster Christopher Post, who is in his 12th year at the school. “There’s no better, more meaningful example of that than people who have led lives of service and sacrifice like our veterans have.”

Housing more than 10,000 artifacts and documents identified to specific service people, the 2,200 square-foot facility—previously a cafeteria that was converted three years ago—is a living, breathing monument to military veterans and their history. The exhibit hosts more than 3,500 visitors annually, including veterans groups, senior citizens, community associations, and students from surrounding schools.

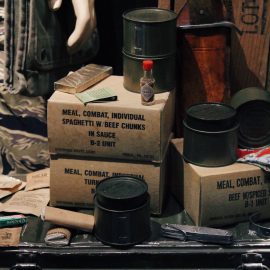

Organized chronologically, each section is dedicated to a different wartime. Viewers could easily spend a considerable amount of time studying each of the displays, which are, in essence, life-size dioramas showcasing every imaginable type of memorabilia and mannequins dressed in uniforms true to the time. Each mannequin represents an actual person who has served, and many of them are Boys’ Latin alumni—which allows Maisel to put a face to a name for his classes.

“I teach on a more personal level,” Maisel says. “I know the stories of the people in here and others. This is really about people.”

The layout is painstakingly tended to by Maisel, who has been collecting since the early 1970s. He co-curates the exhibits with his son, Chris, a first lieutenant in the Maryland Army National Guard—devising a strategy for how best to display everything. What started as a hobby has developed into his life’s work. Quiz him on anything and he has a document, piece of history, or story related to it.

“We have enough artifacts that would fill the whole museum again without display cases,” he says of the personal collection he’s amassed in two separate storage sheds.

He has a longtime affiliation with the military, as his father is a decorated World War II veteran and he himself attended McDonogh School—which was a military school at the time. Maisel’s brother was killed in combat in Korea, and some of his belongings are memorialized in the museum, as well. Through his collecting, Maisel has forged connections and friendships with those who share his passion, establishing a pipeline for trading and sharing artifacts with collectors across the country.

Though he has seemingly dedicated his life to telling the stories of veterans, Maisel doesn’t talk about specific battles all that much—Boys’ Latin has history classes for that. In some ways, this allows him to get into the intricacies of military history and culture. The tenets of his classes surround uniforms, weapons, equipment, tactics, medical care, and military stories. It’s one thing to speak in the abstract about these things, he says, but it’s another to allow students the opportunity to see and touch actual pieces of history.

While most of the museum is static, Maisel offers one rotating display case in which he—along with the input and influence of students in his senior-level museum curation class—is able to showcase his massive back catalog of artifacts tailored to a particular theme. Past exhibits have centered around music, the history of camoflauge, female army nurses, and the 20 artifacts that mean the most to Maisel personally.

“In general, this country often doesn’t fully appreciate some of these things,” Maisel says. “It does start to fade, but that’s why museums are important. You can’t have your history disappear.”

One of Maisel’s main goals is to connect his students with the country’s past while they’re young. He assigns a paper in which students talk with a relative or friend who has served. One class even interviewed Vietnam veterans for the Library of Congress. These are often heavy, emotional experiences that define and stretch the boundaries of education. The way Boys’ Latin sees it, there is no substitute for the real thing.

“Our boys learn best by having real-world, hands-on application of material,” Post says. “This an active workshop, and they can understand for themselves there’s an idea that’s greater than the immediate needs of a 16-year-old boy.”