News & Community

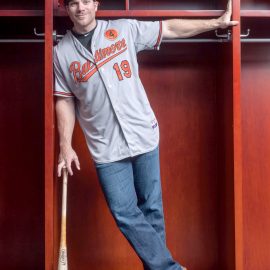

Crush Worthy

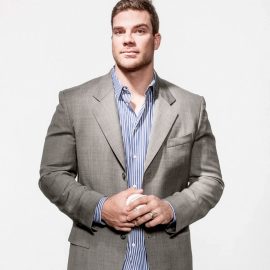

Orioles slugger Chris Davis discusses his ups, and many downs, on the path to becoming a superstar called Crush.

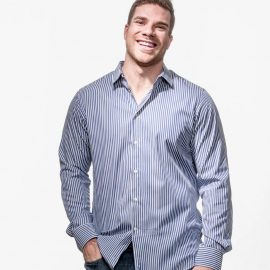

Chris Davis is sweating. Outside it’s another frigid January day fit only for penguins and polar bears, but inside Camden Yards last season’s Most Valuable Oriole has just finished his morning workout, a term that means something different to him than it does to you and me.

During the offseason, he puts in four to six hours in the gym four days a week. Two days from now, 15,000 fans will bundle up for a trip to FanFest, where they’ll fawn over the slugger and daydream of opening day, which in this current snowy and shivery reality seems like an unattainable mirage. Davis knows it’s not.

“Today was lower body,” says the chiseled 28-year-old. “It was miserable. I really enjoy the gym, but there are always things that you don’t enjoy doing. Those are the things that put you at the top. There are days I don’t want to focus on shoulders, or hip mobility, or flexibility, but I know it’s going to pay off in the long run. We usually start out with cardio and conditioning. Some days we’ll focus more on lifting. I’m not going to give away all my secrets, but there’s no doubt I’ll be in shape when we get to spring training.”

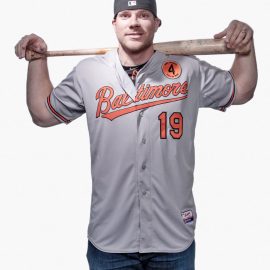

A month later, in a ballpark that seems a world away, Davis steps to the plate in the third inning of the Orioles spring training home opener in Sarasota, FL. The temperature is a blissful 71 degrees, and most fans wear hats to shield themselves from the bright sun. Davis digs in, waves his 35-inch, 33-ounce bat like it’s a toothpick, then calmly blasts a double, scoring two runners to give the O’s the lead. No doubt he’s in shape.

Baseball, as everyone who’s ever played it knows, is a hard game. A game of failure. No one understands this more than Chris Davis, who, at times before becoming the Orioles single-season home run king and morphing into a superstar called Crush, often could barely make contact with the ball.

“Everybody in their life is going to struggle at some point,” he says in the nearly empty Oriole Park clubhouse. “It’s how you bounce back. There were times when I was extremely frustrated. I was almost lost. But I always kept my head up, I always stayed positive. There’s a reason why I’m still here.”

Close your eyes and imagine a typical Texas town. What you’re probably picturing—a small city of farms, ranches, and three high schools where football is religion—is Longview. Davis grew up in the community of roughly 80,000, about 120 miles east of Dallas, and still thinks of it as home. When Chris was 3 years old, his father, Lyn, noticed that his son could toss a ball in the air and hit it with a Whiffle bat. He started him in tee ball the next year and served as his primary baseball coach until he got to high school.

Davis was a big kid, 6-foot-3, 215 pounds when he graduated from Longview High. A former quarterback on the football team and current shortstop on the diamond, he was drafted by the New York Yankees with the third-to-last pick of the 2004 draft. But like just about every boy in the Lone Star State, Davis dreamed of becoming a Longhorn, so he passed on the pinstripes and enrolled in the University of Texas on a baseball scholarship.

It was in Austin that Davis first tasted failure. While he added 10 to 15 pounds of muscle and was “stronger than I’ve ever been,” that power didn’t translate to the field. After fall of his freshman year, he transferred to Navarro Junior College, coached by Skip Johnson.

“He was happy-go-lucky, really a guy that worked at it. But he tried too hard,” Johnson says in a Texas twang. “Chris had power to all parts of the field that wasn’t polished yet. He’d swing too hard. But he always loved to play, loved to have fun and compete.”

Davis credits Johnson for helping him mature both on and off the field, and to learn to respect the game. The men are still close friends and go hunting together in the offseason.

After a stellar season at Navarro, Davis was drafted in the 35th round of the 2005 draft by the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim, but again didn’t sign, betting that he would be a higher pick the following year. The gamble paid off. In 2006, his beloved Texas Rangers took him in the fifth round and offered him a $172,500 bonus. This time he autographed the contract.

“I didn’t come from a lot of money, so I thought that was a good chunk of change,” says Davis, whose father works at a family-owned furniture store and whose mother, Karen, is an adjustor for Farmers Insurance. “I was excited, but it wasn’t so much about the money as it was getting an opportunity to play and feeling like I was ready.”

Davis tore through the minors, treating pitchers like he did that tee ball in the backyard of his childhood home. The Rangers called him up in June 2008. He hit a home run in his first start, but his inaugural at-bat the night before wasn’t quite as glamorous.

“I came up as a kid with a lot of power,” says Davis, who made his MLB debut at 22. “I remember my hitting coach in Single A told me, ‘You only get one chance to hit the first pitch you see in the big leagues for a home run.’ Of course I go up there thinking, ‘I’m gonna go deep my first at-bat because there’s no other way to go.'”

The pitcher had other ideas. He threw Davis a slow sinker, low and inside, the kind of nasty pitch that gives rookies night sweats.

“I was so jacked up that I hit a little nubber off the end of my bat to third base,” Davis says, laughing. “I beat it out. So my claim to fame was I hit 1.000 in the big leagues for a day, which I thought was hilarious.”

The can’t-miss kid, playing for his hometown team in the majors, it seemed so tidy—like a script from a movie. Perhaps the baseball gods thought it was a little too perfect.

“Do you know what the difference between hitting .250 and .300 is? It’s 25 hits. Twenty-five hits in 500 at bats is 50 points, okay? There’s six months in a season; that’s about 25 weeks. That means if you get just one extra flare a week . . . you get a ground ball with eyes, you get a dying quail—just one more dying quail a week and you’re in Yankee Stadium.” —Crash Davis – Bull Durham

Suddenly, after a lifetime of ground balls with eyes, Chris Davis couldn’t get that dying quail. In 113 games with the Rangers in 2009, he hit just .238, and, in 2010, just .192 with one lonely home run. In both seasons, he shuttled between the majors and minors. When Texas finalized its postseason roster in 2010, Davis wasn’t on it.

“I always thought, ‘I have the talent, that’s going to take me as far as I want to go,'” he says. “But when they take your confidence, you really find out what you’re made of. I wasn’t taking care of the things that I needed to take care of off the field that I needed to be successful on the field. Not that I wasn’t working hard, but my heart just wasn’t in the right place.”

If Davis wasn’t a drunk, he certainly was a drinker. Beer, liquor, he’d down whatever you gave him. His routine was ballpark, bar, bed; ballpark, bar, bed. His life had become a Groundhog Day.

“I thought that, as long as I worked hard and was a good person, things were just going to work out,” he says. “I was going hard at both ends. I would drink, I would go out. I’m a guy that you’re not going to have to kick in the butt to motivate, but you’re going to have to pull the reins back to make sure that I slow down. That was how I drank. I’m going to work out, I’m going to play a game, and then I’m going to go home and drink hard. I didn’t understand how to do it the right way.”

Watching Texas in the 2010 World Series as a spectator was a wakeup call. Davis’s teammate, Josh Hamilton, won the AL MVP that season after some much publicized battles with drug and alcohol addiction. Now sober and devoutly Christian, Hamilton became a mentor of sorts to Davis.

“He was just a young kid trying to figure some things out,” says Hamilton, now on the Angels. “I talked with him about where I was in my life and the things that were important to me. I let him know about my faith and the path it takes me on. We discussed some things in my past and the consequences my actions had. Mostly, I reinforced how much preparation it takes to play this game. You can’t cheat yourself or be unprepared. It will show. He always kept an open mind and allowed faith to come into his life.”

Davis, who was raised Baptist, says, over time, sports grew to become his god. He credits his renewed faith with his renewed happiness in baseball, and in life. These days, Davis says he rarely drinks.

“I started dedicating my time not just to me, but to my family,” he says. “I made sure that the way I treated people was the way I wanted to be treated. You realize what’s important when something that has been so important to you your whole life is taken away from you. You realize that someday this game is going to be taken away from you.”

Around this time, Davis met his now-wife, Jill, at a Tex-Mex restaurant in Dallas. “I went down to the Dominican in the offseason of 2010, and she ended up coming down there and staying with me for a month,” he says. “I didn’t have any family down there, and we really grew as a couple. I thought, ‘If this girl is willing to come to a foreign country and hang out with me, she’s worth it.'”

A year later, he proposed over a candlelit dinner on the beach in Maui, and the couple married in 2012. They’re expecting their first child, a baby girl, any day now.

“We all have the choice to live our lives in a certain way,” says Davis, who reads the Bible daily and has several passages tattooed on his body. “We’re not called to judge, we’re called to love.”

Still, his clearer focus off the field didn’t lead to better results on it. In 81 games with the Rangers in 2011, he hit just three homers. At the trade deadline in July, he was regarded by most as an afterthought in a deal that sent Tommy Hunter to Baltimore for Koji Uehara. Davis was elated.

“I already bought [an Orioles] hat and a T-shirt,” he told MLB.com at the time. “It really does feel like a fresh start.”

“Man that ball got outta here in a hurry. I mean, anything travels that far oughta have a damn stewardess on it, don’t you think?”

—Crash Davis – Bull Durham

Ed Ebner is wearing a Chris Davis jersey, and he’s not alone. Davis’s No. 19 is the most prevalent jersey at FanFest, and quite a few young women are wearing “I have a crush on Crush” T-shirts.

“He seems to be a player that I can have faith in,” says Ebner, an O’s season ticket holder from Prospect Park, PA.

No one could have imagined this adulation when Davis became an Oriole. Andy MacPhail, then the O’s president of baseball operations, was enamored with Davis’s potential, and refused to trade Uehara for Hunter straight up. When he offered to throw in about $2 million, Texas agreed to part with Davis.

“Sometimes you’re better off when you’re not in a pennant situation,” MacPhail says. “This was a good ballpark for him to hit in, plenty of opportunity for him to play. We knew he was going to get at-bats. He could rest assured that if he goes 0-4, he’s not going to be out of the lineup tomorrow.”

“There were times in Texas when I had a terrible game, and I would sit the next day,” Davis says. “There were other days when I had a good game, and then I sat the next day. It got into my head. I kept thinking, ‘Am I ever going to get an opportunity to just go?'”

It came here. He emerged in 2012, when he hit 33 HRs, and exploded in 2013, when his 53 dingers and 138 RBIs led the majors.

“I’ve known Chris for a long time and seen him mature and grow as a player,” says teammate and friend Darren O’Day. “His talent has always been obvious. What I think has changed in Chris is he’s gotten much better in terms of his mentality. He’s figured out how to come back from a bad at-bat, or a bad swing, and be ready for the next pitch. He’s figured out that failure is part of the job and he’s bringing a more consistent approach in his head to the batter’s box.”

Davis’s seemingly sudden success and mesmerizing power brought whispers of steroid use. He’s repeatedly denied ever using anything illegal, but the chatter hasn’t dissipated. “There was a time last year when it was frustrating,” he says. “It comes with the territory. People are always going to question you when you’re successful, whether it’s in baseball or anything else.

“For so long, baseball had such a black eye with steroids. A lot of people were hurt that guys were using them. I get it, I understand. I was a fan. I was there when McGwire and Sosa were hitting balls out every other night. Hopefully, it will die down over the next few years. I think baseball has done an outstanding job of implementing a drug-testing policy and a list of banned substances. We have all the information that we need.”

Davis does swear by one PED—performance enhancing drinks.

“I don’t eat a lot of garbage food,” he says. “Trust me, there are nights when I’ll go crush hamburgers, but, for the most part, I try to take good care of my body. I don’t take a lot of vitamins, I don’t take a lot of supplements. After I work out, I want to feed my body what I just deprived it of, so I’ll make protein shakes using almond milk, protein powder, and strawberries, bananas, apples, pineapple, stuff like that. It gives you a lot of vitamins in a quick little shot.”

His strength inspires awe amongst his workout partners. Former Oriole Brady Anderson is one of them.

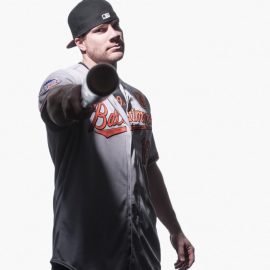

“He can toy with weight, but the numbers really wouldn’t do justice to how strong he is,” Anderson says. “What puts it in perspective is watching him break the bat and hit a home run. He hit a ball in Yankee Stadium where the centerfielder jerked backward, which made me laugh. It was a dead center home run on a ball that he didn’t hit very well. That’s what separates him.”

A free agent after next season, Davis appears poised to be a fixture in the middle of a major-league lineup for years to come. Whether it’s in Baltimore is the key question. “I’ve said it before, I’ll say it every day: I love being in Baltimore,” he says. “This has really felt like a second home to me. It’s hard not to fall in love with this city and this fan base.”

Judging by his reception at FanFest, the feeling is mutual. Davis plays the game with confidence and humility, not fear or arrogance. Perhaps that’s why he was an All-Star last year, while Bull Durham‘s Crash only sniffed “The Show.”

He’s hungry. After devouring a turkey sub for lunch, he heads back to the weight room for yet another mid-winter afternoon training session. There’s always more work to do.