Editor’s note: This article was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

The Baltimore Police Department’s aerial surveillance pilot program likely strayed outside its own civil liberties assurances by tracking some Baltimoreans over multiple days and failing to delete images after 45 days, according to a new report by New York University’s Policing Project.

The city’s recently concluded Aerial Investigation Research (AIR) pilot program, better known as the “spy planes,” launched into the skies over Baltimore in May. The six-month police department experiment was aimed at helping identify suspects or others linked to violent crimes—primarily murders, shootings, and armed robberies.

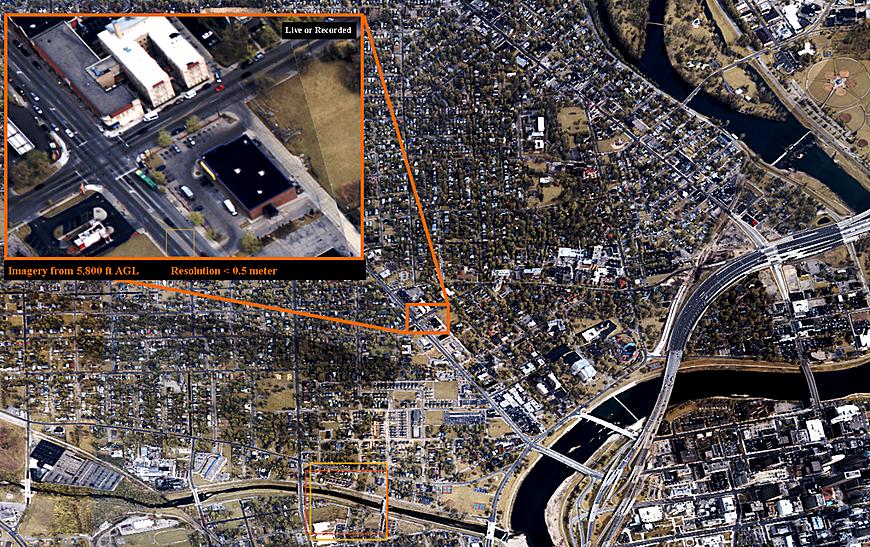

In public statements and contract documents, the Baltimore Police Department and private company, Persistent Surveillance Systems, have stated that the Cessna plane’s 12-camera array would only record “short-term surveillance” and track images “linked to a crime scene” based on police requests for that data. The BPD has repeatedly emphasized privacy limits, assuring that individuals would not be tracked over multiple days (the planes did not fly at night) and that any imagery data not related to investigations leading to arrests would be “stored for 45 days, after which point it will be deleted.”

The Policing Project at NYU School of Law found that’s not exactly how things went down.

For example, city police asked Persistent Surveillance Systems to track “any vehicles that may be arriving or leaving” a home belonging to “the mother of the person of interest” (not a crime scene), according to the NYU audit. One vehicle’s movements in mid-July were later tracked during several days as the AIR program captured the same automobile stopping at nine street addresses and two gas stations—noting that, on one day, “a female [was] observed driving Vehicle 1.”

The aerial surveillance alone, Persistent Surveillance Systems and police maintain, cannot specifically identify people. But, as the NYU report emphasized, the pilot program did not solely rely on the plane’s wide-area imaging system. Instead, the AIR program utilized the private company’s software, iView, to integrate BPD’s network of ground-based tech, including CCTV cameras and automated license plate readers. In that way, the whole surveillance package identifies people’s faces and their vehicles, according to NYU. This integrated network was also noted in the police department’s contract with Persistent Surveillance Systems, though not widely discussed publicly. That contract also enables PSS to use the Baltimore Police Department’s computer-aided dispatch, CitiWatch (which includes other private, business, and residential surveillance cameras) and Shot Spotter information to “make all of the systems work together.” The Ohio-based Persistent Surveillance Systems—founded by former Air Force Col. Ross McNutt, who earned a Ph.D. from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and first deployed his technology to track Iraqi insurgents—also owns that synthesized data, the contract notes.

In a statement on Friday, the Baltimore Police Department says it stuck to the contract limits, repeating that any aerial images not linked to an arrest will be deleted “after 45 days,” and that aerial imagery of people’s movements in the city was captured “only during the day and never at night,” meaning the program “did not allow for continuous, long term-tracking.” In a Dec. 6 court filing, BPD attorneys admitted the surveillance program specifically tracked the vehicle for short-term tracks on multiple days.

NYU’s Policing Project was brought on by the Baltimore Police Department to audit civil liberties and civil rights issues related to the pilot project. The research was conducted with no expectation of outcomes, project leaders say. The $80,000 evaluation was funded by Arnold Ventures, a data-oriented philanthropic LLC that also paid for other outside evaluations, as well as the $3.7 million aerial surveillance pilot itself.

Among NYU’s findings: For the most part, BPD abided by its contract and public statements “with a few significant deviations.” The six-month Aerial Investigation Research pilot was advertised as a means of tracking individuals “to and from crime scenes,” yet the BPD also issued “supplemental requests” not mentioned in the contract, including requests for data not tied specifically to crime scenes. “Much more data is being stored, and for far longer, than public statements would suggest,” the NYU report found.

Because of where the surveillance planes fly, and where ground surveillance is located in Baltimore, the program “inevitably involves disparate racial impacts,” NYU investigators found.

“The AIR Program presents serious concerns about individual liberty,” the Policing Project noted, proposing stringent privacy limits and lamenting the lack of democratic approval via an elected City Council. It was Baltimore’s bureaucratic Board of Estimates, which approved the agreement championed by then-Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young in April. “AIR collects data on countless Baltimoreans daily,” the report added, “the vast majority of whom have done nothing wrong.”

Overall, the program’s image retention policy is about as clear as the fuzzy human “dots” police and PSS have not-quite-accurately described as “pixels” (vehicles, in fact, can clearly be made out as such). In recent federal court filings involving the ongoing dispute of the project’s constitutional legality, BPD attorneys said movements of people linked to crime scenes, known as “event tracks,” could not be separated from other daily footage stitched together for 30-plus mile views of the city, calling the issue “a ‘matter of semantics’ (e.g., the meaning of the word ‘image.’)”

“This debate is anything but semantic,” countered Farhang Heydari, executive director of NYU Policing Project, whose brief last month prompted the BPD’s response. Heydari says the indefinitely saved data is “readily available for additional future viewing and searching. That isn’t much of a deletion policy at all.”

Brett Max Kaufman, senior staff attorney in the ACLU’s Center for Democracy, said the NYU report shores up why the ACLU filed suit against the aerial surveillance program in the first place. “This really just confirms what we have been concerned about and why we thought this program is unconstitutional,” Kaufman says. “We laid out not only why it was possible for government to track people across days, but why it absolutely was part of the intention of the program.”

In April, the ACLU of Maryland, representing Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle and other community advocates, unsuccessfully sued to block the six-month pilot in Baltimore—the first program of its kind in the nation—as a “historical surveillance battle,” citing potential violations of individuals’ First and Fourth Amendment rights. AIR’s last flight landed on Oct. 31, and it’s unclear if the program will resume. Newly sworn-in Mayor Brandon Scott has voiced opposition, saying there’s no proof it works and voicing concerns about residents’ civil rights.

In November, a three-judge panel of the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a lower federal court ruling, which had allowed the pilot (even though the planes were grounded since the six month-period was over at that point). That opinion, and the NYU report, has set off a recent flurry of legal filings, including a supportive brief by the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to request a rehearing of the case, and noting the program, if continued, would further erode community trust in police and “create additional opportunity to exacerbate racial disparities in policing.”

The aerial surveillance program, however, does have some support in the community, including among churches and organizations now urging the city to launch the planes once again. Joyous Jones is a staunch supporter and an elder at Simmons Memorial Baptist Church, whose parishioners witness open market drug dealings and shootings on nearby streets.

“NYU cannot come into Baltimore to tell us what we need,” says Jones, who has comforted mothers grieving over the loss of their sons to street violence. “They can’t speak for me and for the citizens of Baltimore.”

Mid-term AIR data provided by another BPD-contracted program evaluator, RAND Corporation, in September indicated a slight benefit in crime-solving using aerial surveillance technology. Nineteen of 107 cases (17.8 percent) aided by air evidence were “provisionally closed with arrest” between May 1 and August 20—including six homicides. That data was compared to 124 of 874 target crime cases (or 14.2 percent), in which police made arrests without any help from the plane. The percentage difference: 3.6 percent. The Baltimore Police Department said the data was not complete and drew “no conclusions” about its effectiveness.

That hasn’t stopped PSS, and its owner, McNutt, from closing in on deals elsewhere. A three-year agreement is now being considered by the St. Louis Board of Aldermen, with one alderman on Friday promising the program “would have a significantly positive effect.” St. Louis suffered 247 homicides by Dec. 6, with 179 unsolved. That city’s program, funding to be determined, would track a wider array of crimes beyond the Baltimore Police Department’s four categories of homicide, shootings, car-jackings, and armed robberies. The St. Louis proposal would include burglary, arson, motor vehicle theft, drug trafficking, felony larceny from a motor vehicle, and illegal dumping.

David Rocah, senior staff attorney at the ACLU of Maryland, described the group’s battle against the aerial surveillance project as an “Orwellian nightmare come to life” in Charm City.

“If we do not stop it here,” Rocah said, “this technology will surely spread and trample the rights of people in other cities across the country.”

Edited by senior editor Ron Cassie.