Climate change is already wreaking havoc on the city’s infrastructure and public health. How will Baltimore cope with the staggering challenges to come?

News & Community

Hell and High Water

Climate change is already wreaking havoc on the city’s infrastructure and public health. How will Baltimore cope with the staggering challenges to come?

Deion Young was taking a rainy Sunday nap when a buddy shook him awake and dragged him to the porch to witness the raging river suddenly bursting past his mother’s rowhouse. When the pair looked up the block, they saw the water wasn’t just coming down the street but flowing sideways, too, out from people’s front doors. By the time the 23-year-old Young turned around, water was coming up through his family’s basement and filling their living room, too.

Next door, Warren Brown, watching TV at his mother’s home, heard the rushing street water and then realized the surging flood was busting through the back door of their finished basement. “Mamma, it’s here,” he yelled to Joyce Fisher, his 89-year-old mom, who was on the phone with a friend in her second-floor bedroom. Just moments later, she couldn’t get downstairs. In the rowhouse on the other side of Fisher, a senior woman trapped alone dialed 911.

A half-mile downhill in the Beechfield neighborhood of Southwest Baltimore, the situation had become dire.

Eight people stood stranded inside an MTA bus surrounded by seven feet of water, which was now tearing up trees and chunks of Frederick Avenue concrete and asphalt and pushing cars into the divots. A family of five, including two children and an infant, climbed from the windows of their Toyota Camry onto the car’s roof, hoping to be rescued from the cresting, manhole-popping brown waters, which had overwhelmed the city’s culverts, drainage pipes, and sewage system. Four others clung for life to a chain-link fence. (Fire Department first responders in motorized boats made 20 rescues.)

THE 5000 BLOCK OF FREDERICK AVENUE IN SOUTHWEST BALTIMORE CITY DURING LAST MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND'S FLOOD. Keith Fields

At the same time, floodwaters rose to the ceilings of Frederick Manor’s basement apartments, where residents carried children to safety on their shoulders. “People were panicking,” says Keith Fields, a father, who lives in a second-floor apartment in an adjacent building. “They were running out of their homes right into water mixed with raw sewage. You could see the fecal matter.”

Emergency responders located one woman, who was swept away while fleeing her drowning car, behind a stretch of rowhouses. A dog, also later found okay, got caught in the high water, too.

When it finally receded, last Memorial Day weekend’s devastating flood had damaged 200-plus homes in the Frederick Avenue corridor. Many households still haven’t recovered. Joyce Fisher has been without a refrigerator, oven, dishwasher, and washer and dryer since last May. She keeps her milk, fruit juice, and yogurt in a cooler packed with ice on her back porch. Her basement, like Young’s, which had been his sister’s bedroom, remains uninhabitable. In many homes, rounds of mold remediation continue. Some have suffered worse.

“We only recently learned three families went the entire winter without heat or hot water because their furnaces were ruined,” says Pastor David Franklin, of nearby Miracle City Church, whose volunteers are still helping to clean, repair, and paint local homes. “It’s heartbreaking.”

Even if you live in Baltimore, the massive flood, which drew FEMA, Red Cross, and NGO disaster teams to the city, likely does not ring a bell. That’s because six miles west, the same catastrophic weather event leveled Ellicott City’s historic Main Street for a second time in three years. That the crisis in the low-income, majority-black neighborhood—also hard hit by the 2016 storm that struck Ellicott City—drew such comparatively little attention certainly raises a red flag about media coverage of at-risk, minority communities. “TV Hill is still in the same place,” says Michael Martin, pastor of Stillmeadow Community Fellowship, which provided food and shelter to residents and first responders in the aftermath of the Frederick Avenue flood. “Those television crews practically had to drive past us to get to Howard County.”

It also raises troubling concerns about the city’s adaptation to climate change amid our already-crumbling infrastructure; who is bearing, and who will bear, the brunt and costs associated with climate change; and which communities have the resources to cope and which need assistance. One often-overlooked example of Baltimore’s infrastructure crisis: the City is nearly a billion dollars behind in deferred basic maintenance of its public buildings and facilities, 68 percent of which received failing grades in an internal Office of General Services report this year. That’s apart from the city’s schools, which are the oldest in the state, lack air conditioning in more than 60 buildings, and face a maintenance backlog of almost $3 billion. And then, of course, there's the blight of 16,000-plus vacant houses Baltimore has never figured out what to do with.

A full year later, the City has yet to begin a hydrology study of the Frederick Avenue flood, much less work to prevent the next one. The Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management has its fingers crossed a FEMA grant to fund an investigation will come through.

The only assistance the City has offered Beechfield residents laboring to replace lost automobiles, appliances, and furniture, not to mention drywall and flooring, is help filling out low-interest federal loan applications, which they note can be used to relocate, if so desired. It’s reminiscent of the advice Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross gave to budget-strapped, furloughed federal workers that they take out bank loans to get by.

Meanwhile, two smaller but significant downpours subsequently beset Beechfield basements again in July and August, adds Martin, highlighting the toll the repetitive flooding has taken on his community. “You can see it tearing apart the fabric of the community,” he says. “Families here for decades are trying to sell their homes, not that they’re going to get a lot for them. It’s just traumatic for folks, many of whom are running on vapors as it is.”

Meanwhile, first-term City Councilman Kris Burnett is scrambling to respond. “Did I run on climate change?” Burnett, who represents Southwest Baltimore, asks rhetorically. “Was it a part of my platform? No. But here I am trying to deal with its consequences every day.”

Heavier rainfalls, a hallmark of global warming, are up 55 percent in the region since 1958. Two-day events, such as the one that devastated Beechfield, are up 92 percent, according to a 2018 study of urban flooding by the University of Maryland and Texas A&M. Frederick Avenue is hardly the only example of repetitive flooding. Intersections in Fells Point flood with each new downpour and evacuations of Clipper Mill Road and Mount Washington when the Jones Falls breaches its banks have become routine. Now consider the deluges overmatching the city’s aging drainage system and shortsightedly built environment—also creating a frightening spike in sinkholes—will significantly worsen.

Forget the notion that we have 12 years to stave off the gravest effects of climate change, a misleading deadline at best. Climate change is a continuum, not a cliff. C02 remains in the atmosphere for decades, some of it much longer, and regardless, global emissions set a new mark in 2018 and are expected to again in 2019. Even if all carbon dioxide ceased today, the climate will continue to warm for hundreds, really thousands, of years, as Daniel Schrag, a professor of geology and environmental science and engineering at Harvard, has said. “A silver-bullet solution is not around the corner,” he adds. “It will require innovative [adaptation] investments sustained for at least the next century.”

Warmer temperatures, a foregone conclusion, inevitably lead to more water vapor in the atmosphere and stronger, more frequent storms.

“Baltimore is not alone. The kind of flooding it’s been experiencing we’ve seen a lot of on the East Coast and Gulf Coast in the last five years,” says Gerald Galloway, a University of Maryland professor of engineering who co-led the urban flooding study. “People are beginning to realize it’s a long road we are going down. The questions are what can be done to help people who don’t have the resilience to recover, and how to do you fix an infrastructure problem when there’s not a big economic return?”

BALTIMORE'S PROJECTED CLIMATE IN 2080 WILL RESEMBLE CLEVELAND, MISSISSIPPI: 9.1°F WARMER AND 58.5 PERCENT WETTER IN THE WINTER.

THE UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND CENTER FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE

According to new modeling, Baltimore’s 2080 climate will resemble that of steamy Cleveland, Mississippi, a town of 12,000 in the heart of the Delta with annual average high temperatures more than 7 degrees hotter than we currently experience. They receive nearly 35 percent more rain and have, as one would imagine, less concrete and more green space to soak it up. In getting your head around the profound nature of that shift in the ecosystem, consider your own body’s reaction when its baseline temperature rises a few degrees above normal. Farmers in surrounding counties who bring their produce to Baltimore’s beloved JFX farmers’ market, many of whom struggled with last year’s record rain, will battle intense rain and drought cycles. Plants, insects, and birds will all be on the move. The chief scientist of the National Audubon Society said after a 2015 study that the Baltimore Oriole, the state bird, “may no longer nest in the Mid-Atlantic, shifting north instead to follow the climatic conditions it requires.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources say warmer winters are already reducing oyster populations.

But Baltimore’s most pressing issue is not street flooding, even as it also imperils a whopping 8,000 structures designated as historic—City Hall, War Memorial Plaza, Shot Tower, President Street Station, Zion Lutheran Church, and the Peale Center, the oldest museum building in the United States, to name a few. (As part of an ongoing $4-million renovation, the Peale Center’s utilities were moved from the basement to the third floor, and aquarium-strength glass was added to support lower-level windows.) Nor is it sea-level rise, which poses an existential threat to the Inner Harbor and Fells Point. Nor is it even the documented warm-weather increase in tick survival and Lyme disease, and the 40-day expansion, since the 1980s, of mosquito season and the increased potential for scary vector-borne diseases such as West Nile virus, dengue, chikungunya, and, of late, Zika.

No, the city’s most urgent infrastructure problem is the continually inundated, century-old sewage system that sent human waste hurtling into more than 5,100 residential basements last year. Seventeen years under an EPA consent decree to fix its broken sewage system and $1 billion in repairs later, backups have instead made a nearly tenfold jump. (One woman near Pimlico settled a lawsuit after 10 sewage backups in five years.) Baltimore’s asthma hospitalization rate, among the highest in the country, and premature-death rate due to air pollution, the highest in the country, leap out as the other most urgent climate change-related issues.

Nearly one-third of all Baltimore public high school students self-report a diagnosis of asthma, which is associated with indoor mold—think heavy rains again—among other factors. Longer and more intense pollen and allergy seasons as spring temperatures rise earlier don’t help. Asthma rates are 50 percent higher for families below the poverty line, and it’s the number one reason city students are absent from school.

“What poses a unique problem in Baltimore is that many rowhouses sit right on top of busy commuter streets and highways,” says Amir Sapkota, a University of Maryland School of Public Health associate professor. “We know extreme heat, which is increasing in frequency, intensity, and duration, drives up ozone levels, and we know that this trend will continue.”

These communities are often the same neighborhoods that experience the urban heat- island effect. The result of a combination of concrete and a lack of tree canopy, it means temperatures in some parts of the city can be as much as 17 degrees hotter than other, leafier sections, presenting an additional risk to those with respiratory and cardiac illnesses. No mere coincidence, both the urban heat-island effect, which prevents temperatures from cooling at night as well, and traffic emissions disproportionately impact Baltimore’s historically redlined neighborhoods. As Baltimore artist Olivia Robinson has documented, the city’s tree canopy coincides in near-lockstep with the FHA’s infamous 1937 Baltimore redlining map. Neighborhoods that were lower prioritized for loans then have less leaf cover today.

“I don’t think people, by and large, are making the important connection between urban health issues and climate change,” says Morgan State professor Lawrence Brown, whose research focuses on community health. “It is linked to a legacy of redlining in the city’s planning, housing, and public works departments, and, over time, a legacy of ignoring the consequences of that planning.”

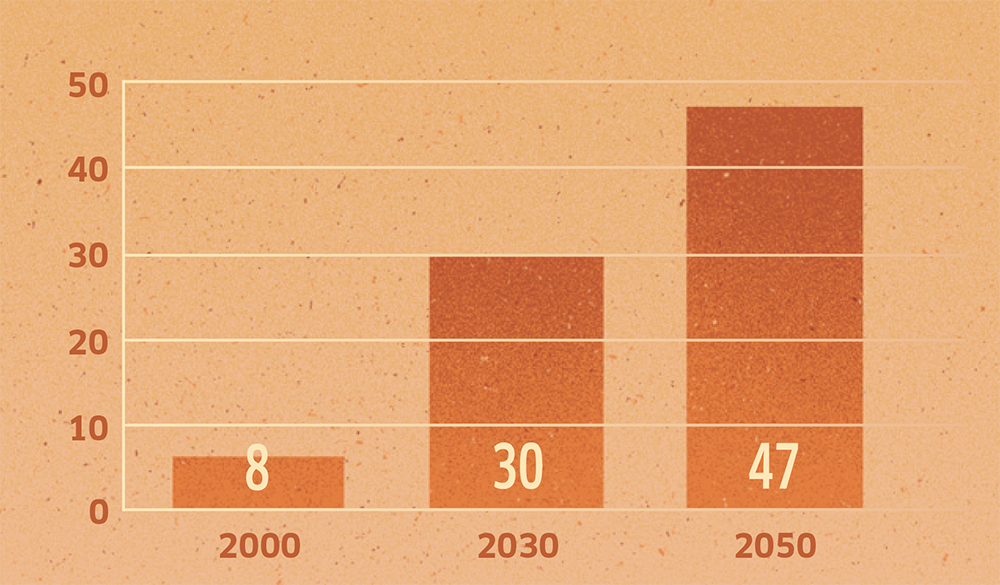

We’re not done yet. Now consider that by mid-century, Baltimore will face nearly 50 days a year with a heat index above 105 degrees. Office of Emergency Management director David McMillan, whose department responds to floods and crises of all stripes, says it’s not the thought of floods that keeps him awake at night but heat waves, like the ones that killed 739 people in Chicago in the mid-’90s and tens of thousands in Europe in 2003. Annual heat-related deaths in the U.S.—Baltimore had 13 last year—far surpass fatalities directly related to any other weather-related event. More deadly at the moment: Out of every 100,000 residents in the city, an MIT study estimated 130 people in Baltimore were likely to die prematurely each year of causes related to air pollution, more than in New York or Los Angeles.

“There is still the tendency to think of climate change as a future event or one that impacts the habitat of polar bears or the survival of Bangladesh,” Sapkota says. “We need to see that auto emissions and global warming are killing our own neighbors today.”

Heat Wave

DAYS IN BALTIMORE WITH HEAT INDEX ABOVE 105°

Climate Central

It is beyond disconcerting that city officials have never bothered to resolve the chronic Beechfield flooding, which has caused repeated evacuations since the 1970s and one known fatality. In 1981, the body of a young woman named Lynn Schaeffer, who was trying to escape rising waters surrounding her car, was found pinned under an overturned vehicle. Similarly, the city has never seriously addressed the flooding of the Jones Falls, which floods with ever-alarming velocity and volume. “It’s a miracle there hasn’t been a fatality,” says Kristin Baja, the city’s well-regarded former Climate and Resilience Planner, who left for a national position a year and a half ago but still lives in Baltimore. Instead, city leadership, long beholden to private developers, continues instead to pave the way for development around Baltimore’s floodplains. Just in the past seven years, a sprawling new townhouse and condominium project was built “perched on a hilltop with a picturesque wooded setting,” as one Ryan Homes advertisement described it, overlooking Frederick Avenue just west of Stillmeadow church. The new Uplands homes and apartment development, still growing under continuing construction, near Edmondson Avenue also gets blamed for adding to Beechfield’s problems.

Similarly, Jones Falls flooding has caused millions of dollars in commercial damages in recent years, closing one business in Woodberry and forcing two others, Nepenthe Brewing and Mouth Party Caramels, to pick up and leave for higher ground.

B.G. Purcell, owner of Mouth Party Caramels, suffered two total losses from floods in three years after moving her home business to a Jones Falls site with a commercial kitchen in 2013. The second convinced her to relocate to Timonium. “You get nervous when it rains,” she says, highlighting the difficulty of getting out of commercial leases, flood or no flood. “The anxiety it produces is real. I had smartphone apps that alerted me to every storm and potential flood. Both times I was at the movies. You start thinking, ‘Is tonight the night?’”

Meadow Mill Athletic Club owner Nancy Cushman says runoff and debris from upstream, and the frequency and strength of storms, have risen dramatically since she opened in the early ’90s. By Baltimore County’s estimate, roughly one-third of the lower Jones Falls’ watershed under its jurisdiction is covered by roads, parking lots, and other impervious surfaces. Her first major flood in 2004 dumped two feet of water into the gym. The popular athletic club’s parking lot regularly takes on overflow from Jones Falls. “You just can’t take squash courts somewhere else,” Cushman says, explaining why she’s ridden it out this long. During the 2016 flood, Nepenthe Brewing had baguettes from next-door-neighbor Stone Mill Bakery floating inside their property. Overcoming an estimated $95,000 in damages and closing for a month after that flood, they reopened in Hampden earlier this year.

“For taxpayers, it doesn’t make any sense to have a policy that just requires someone to have flood insurance and then allows them to build or lease anywhere,” Purcell says. (As has been noted before, FEMA’s subsidized National Flood Insurance Program provides protection against financial loss, and also a perverse incentive to build in compromised areas at times.) “At that point, it becomes the Office of Emergency Management’s responsibility to deal with these events that we know are going to happen.”

Former Councilman James Kraft, who introduced legislation to create the Baltimore Office of Sustainability a decade ago, says part of the problem with continued floodplain development is that the sustainability office remains underneath the City Department of Planning. That wasn’t the initial intention of his bill. “I wanted it to be a cabinet-level department, equal to every other department, and report directly to the mayor,” Kraft says. “As it is, the sustainability office raises its concerns, the planning department listens, but they override them.”

Case in point: developer David Tufaro’s renovation three years ago of the historic, 100,000-square-foot Whitehall Mill factory. The building sits even closer to the Jones Falls than his mixed-use Mill No. 1 complex. By guideline, the project was originally required to lift any first-floor commercial, office, or residential space 14 feet above level ground. But Tufaro negotiated a flood protection variance down to 7 feet with the city planning department. Precautions at Whitehall Mill include bricked-in windows and 15 floodgates, similar to those deployed at the Whole Foods Market along the Jones Falls in Mount Washington. At the request of the City, Tufaro built a pedestrian bridge across Clipper Mill Road for evacuation purposes.

Not surprisingly, in 2016, weeks after the first apartment residents moved in, two feet of water entered Whitehall’s garage and seeped several inches into the lobby.

Despite his own development projects around the Jones Falls, Tufaro nonetheless decries the continued construction of brand-new mixed-use commercial and residential buildings around Harbor East, Harbor Point, and Fells Point. “Look,” he says, “the City—and by that I mean city officials—are greedy. If the City cared about these issues across the board, they wouldn’t be handing out tax breaks and TIFs [tax-increment financing packages] and encouraging this stuff to go up.”

Tufaro is upset about the hoops he's had to jump through in contrast, but that doesn’t necessarily make him wrong. Hurricane Isabel's 10-foot storm surge drove water several blocks into downtown in 2003, and it would be more powerful if it hit today given sea-level rise and warmer temperatures. As it was, Isabel destroyed hundreds of cars, closed much of the central business district, and shut down the World Trade Center after submerging its basement utilities.

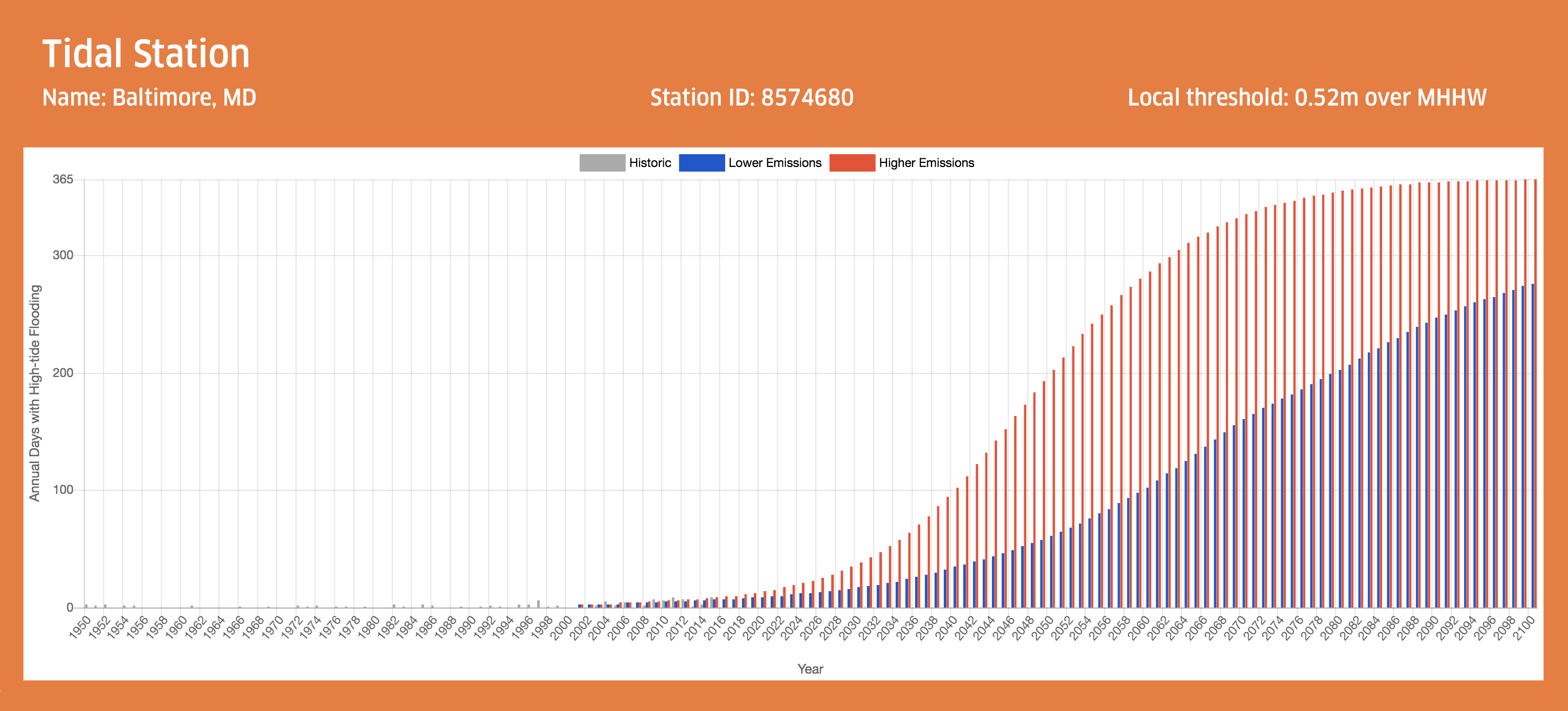

Even without a hurricane, high tide “nuisance flooding” in the Baltimore harbor (see chart at the end of the story) is expected to be a couple-days-a-week occurrence by mid-century. The City, with residents, needs to have conversations about what’s at risk and what can be done to protect the Inner Harbor and Fells Point, Kraft says.

“Think about Ellicott City,” says Preservation Maryland’s Nick Redding. “That’s what we’re looking at if we don’t act.”

THE COLLAPSE OF HALF A BLOCK OF 26TH STREET IN CHARLES VILLAGE FIVE YEARS AGO, BLAMED ON HEAVY RAIN AND AN AGING RETAINING WALL, PLUMMETED 19 CARS ONTO CSX RAIL TRACKS 75 FEET BELOW. Getty Images

The single most startling image of a climate change-associated disaster was the collapse of a half block of 26th Street in Charles Village five years ago. That unsettling spectacle plummeted streetlights, trees, and 19 cars, all thankfully parked and unoccupied, onto CSX rail tracks 75 feet below.

Technically a landslide, it was blamed by a Department of Transportation investigation on heavy rain, which had weakened a 100-plus-year-old stone retaining wall. A video of the collapse, shot by a 26th Street resident as he watched his SUV tumble, went viral, garnering more than 11 million views.

“We took photographs, sent emails, my wife made phone calls and 311 complaints for years,” says Jim Zitzer, a retired electrical engineer who has lived across the street from the collapsed block for more than three decades. “The holes in the street were so big that you could look down through them and see the railroad tracks. The Department of Transportation would come out, patch them, and leave, and they’d open right up again in three weeks. The street was caving in, and no one cared.”

Then late last year, during the wettest November since measurements began in 1871, another block of 26th Street partially collapsed after rain accumulation pushed a second retaining wall section to the brink.

City officials had promised routine inspections of aging infrastructure after the first collapse of the 26th Street retaining wall, which Baltimore taxpayers spent $6 million to fix (and CSX more). But in the nearly four years after the first collapse, officials conducted just a single inspection, as first reported by the Baltimore Sun. A month later, this past December 2018, a major sinkhole, again blamed on heavy downpours, opened up at Lexington and Howard, interrupting light rail service. Weeks later, more rain drove a portion of Federal Hill onto Covington Street and nearly the American Visionary Art Museum.

The list of destruction goes on. In 2016, within six months, sections of three major streets collapsed in Mount Vernon—Centre, Mulberry, and Cathedral—caused by water main failures. In 2015 and 2014, respectively, sinkholes opened on Eutaw Street near the State Center office complex and Riverside Avenue in Fed Hill. In 2012, heavy rains damaged a 120-year-old culvert and opened, and then reopened, a sidewalk-to-sidewalk crater across East Monument Street.

Twelve years since 2003 have surpassed the historical average for rainfall at BWI Airport, with last year topping 70 inches for the first time in recorded history. So far, each month of 2019 is above its historical average as well.

If you’re wondering how Baltimore’s Department of Transportation pays for all the unexpected roadwork that accompanies these street collapses—they don’t. They can’t afford it. It comes from either DPW or general City emergency allocations. Since the Great Recession forced state budget cuts to its highway user revenue program, the City DOT has lost upward of $500 million in funding.

If it sounds like a grim picture, it is. When asked how many potentially vulnerable 80-, 90-, and 100-year-old brick tunnels lie beneath the city, Department of Public Works Director Rudy Chow admits he doesn’t know. He insists there is no way of knowing. “Hundreds,” he offers as an estimate. “There are almost no maps for anything buried underground that long ago,” Chow explains, adding the city beneath the city is being scanned by cameras and documented for the first time as DPW repairs old lines. Similarly, Chow says the City has no real handle on the number of potentially vulnerable retaining walls. “Hundreds,” Chow offers again. (In an interview, DOT Director Michelle Pourciau said a study is underway.) One of the nation’s original port and rail hubs, with tracks crisscrossing neighborhoods all over the city, much of Baltimore’s infrastructure began reaching the end of its natural lifespan decades ago, adds longtime DPW spokesman Kurt Kocher. “When we started to see the first sinkholes, it was probably the mid-’90s,” Kocher says.

Chow recently won a very public battle for a 30-percent, three-year water rate hike, the second of the past decade. A $430-million pipeline-misalignment fix to the Back River Waste Treatment Facility is expected to eliminate a 10-mile backup of excrement extending from Charles Village to the Dundalk plant next year. That work will vastly reduce the sewage overflows dumped in the Jones Falls. However, the completion of the project will reduce but not eliminate basement backups. Many are simply the result of leaky, outlying smaller storm and sewage lines that flood during rainstorms. Sixty-two-year-old Anita Moore has lived in the same West Arlington house since 1975 and says the sewage back-ups in her basement began eight years ago. "It's happened three times now," Moore says. "Four years ago was the first major issue. The freezer was floating in the basement. The City didn't pay for anything. We lost family photos, wedding photos, baby photos, everything. Things that were irreplaceable."

Charles and Doris Brightful, a retired corrections officer and nurse in Grove Park, another majority black neighborhood hit hard by the sewage crisis, have watched four backups destroy their furniture, television, and hot-water heater, as well as family photos and other keepsakes. “You get nervous when it rains,” Charles Brightful says. “Paranoid.”

Incredibly, there are thousands of stories like Moore's and the Brightfuls’, and the worse things get, the more likely Baltimore residents will get stuck with water rates and clean-up bills they can’t afford. With DPW’s goal of replacing 15 miles of water lines a year, it will take a century to update the 1,500-mile city network. That’s not counting 1,046 miles of storm drains and 1,400 miles of sewage lines.

DPW has set up an expedited reimbursement program for back-ups, capped at $2,500, but its guidelines are so stringent that just 15 percent of applicants get approved. They’ve denied all of the Brightfuls’ claims to date, forcing them to pay more than $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs. Meanwhile, the City Health Department has never performed a study of the actual public health consequences suffered by residents and neighborhoods afflicted by sewage backups.

In the long term, the new water and sewage rate increases “are a drop in the bucket, in terms of the coming cost of climate change,” says Dan Nees formerly of University of Maryland Environmental Finance Center, which recently performed climate change “stress tests” for Annapolis and Salisbury. Annapolis’ tourism-friendly city dock flooded 63 times in 2017 from higher afternoon tides.

Nees and the finance center had hoped to do a similar free financial stress test for Baltimore. The city was the first jurisdiction they approached. “They declined,” Nees says. “The thing is, adaptation is not an environmental problem; it’s an infrastructure problem and a financial problem.” The city’s problems are unique, Nees notes, citing schools, poverty, blight, and crime, but they're also interconnected, and Baltimore can't afford to ignore the coming costs of climate change. (The most recent U.S. Census report estimates that the City's population fell by more than 7,300 in the last year, the biggest drop in nearly two decades, which also means there's fewer taxpayers to foot the bill, adding to the bleak fiscal picture.)

Counting on federal help, which isn’t going to come, is another mistake, adds Nees. “It’s a local responsibility. Eighty-five percent of infrastructure projects are locally funded.”

It may be possible over time for the City to adapt to climate change, but it will take political will, resources, and leadership yet to be demonstrated at City Hall. Neither Mayor Catherine Pugh nor former Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake has been accused of making sustainability and climate change adaptation a priority. Rawlings-Blake tore up trees to make room for a failed Grand Prix effort. Pugh pulled up bike lanes and threw the city’s bicycle master plan out the window. Her administration did join a growing list of cities suing fossil fuel companies after being approached by a California environmental law firm representing other jurisdictions with similar cases. It’s a long shot at best.

More encouraging is the rise of the Baltimore Peoples Climate Movement, an intersectional, climate justice coalition, formed after the mobilization of more than 600 Baltimoreans to the 2017 National Peoples Climate March in Washington D.C.

There are solutions, too, that could be put on the table now, given real political demand. The University of Maryland Children’s Hospital operates an RV allergy and asthma clinic on wheels known as the Breathmobile, which visits 20 schools and treats some 500 kids each year. The program, privately funded, costs between $350,000 and $400,000 to operate annually—less than Pugh’s controversial Healthy Holly book deal with University of Maryland Medical System. It's has been effective in lowering emergency room trips, hospital stays, and missed school days by 77 percent among the students. Lisa DiStefano, a nurse practitioner with the Breathmobile, says they've treated kids who have lost immediate family members to asthma, including a student that lost their mother. Danielle Craighead, a school assistant and parent at James McHenry Elementary/Middle in Hollins Market, had to pull her 11-year-old son Xavier out of basketball and lacrosse because of his asthma before the Breathmobile began arriving at his school. "I've taken him to the ER at Bon Secours Hospital in the middle of night," she says. "You get scared to let them go outside and play." Nekia Parrine, another parent at James McHenry, has three children, 11, 13, and 15, with asthma who became Breathmobile clients. "I probably made 15 trips to the hospital trips with them [before the Breathmobile]," Parrine says, adding one her children missed so many school days he was held back a year before successful treatment. "I once had all three admitted to the hospital at the same time."

OEM Director McMillan suggests a low-income air-conditioning fund, similar to BGE’s heating fund, could help vulnerable households cope with summer energy bills. (Although that obviously would not benefit Baltimore's vulnerable homeless population, estimated at close to 3,000.) He also suggests the city could organize a buddy system, where healthy, mobile individuals in each community reach out to isolated seniors and sensitive populations, like the plan implemented in Europe following its deadly 2003 heat wave. Health Department “Code Red Heat Alert” cooling centers are largely ineffective, city employees admit, in reaching those most in need.

“Someone could be across the street, and we wouldn’t even know it,” one worker says.

Reducing transportation emissions, responsible for nearly half of the state’s fossil fuel release, is considered the low-hanging fruit in the climate change equation. Maryland Department of the Environment chief Ben Grumbles said so himself, suggesting in a workshop with climate change experts and journalists that some type of carbon cap and trade deal within the transportation industry and/or a new gas tax could be an answer. His boss, Governor Larry Hogan, however, hopes to expand the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, I-495, and I-270 and build a third Bay Bridge. He also famously cut Baltimore’s planned Red Line transit project and has failed to improve the city’s MTA bus system.

Baltimore does have a new sustainability plan working its way through the legislative process that sets worthwhile goals, including planting more trees. But most of the city’s elected leaders still think almost exclusively in terms of mitigating the city’s carbon footprint and responding to emergencies—and not, for example, potentially buying out the apartment complex and homes at the bottom of Frederick Avenue and building a retention pond.

“In Baltimore, there aren’t climate change deniers in city leadership, but we are not seeing a need to act,” says Baja, the city’s former sustainability chief. She believes the most constructive action the City could take is to pass legislation requiring that sustainability and climate change adaptation be integrated into every department budget process—Planning, Housing, Health, Transportation, Recreation and Parks. It is similar in concept to a charter amendment passed last year requiring City agencies to look at every capital expenditure under the lens of racial equity.

“On a broader level, we need to stop begging people to invest here and bending the rules for them,” Baja says. "That’s not the only way to generate economic development. We need to think bigger and be a vanguard city when it comes to critical sustainability and adaptation that attracts money and support.”

We also have to keep in mind, she adds, that almost every scientific review to date has underestimated the effects and costs of climate change, the number of extreme events, and the greater variability of events.

“We are still planning for what we have seen in the past,” she says. “Anything we look at, in terms of capital expenditures by the city, needs to be based not on past or present but on what we will see.

“We have a whole new future coming.”