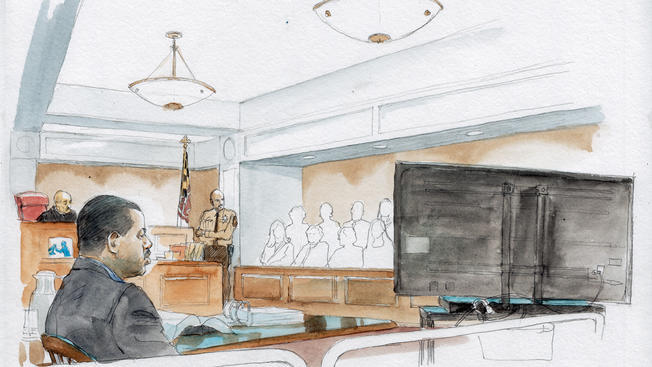

After eight days of testimony, final arguments were made Monday in the trial of the first police officer facing charges related to the death of Freddie Gray.

In her closing statements to the jury, prosecutor Janice Bledsoe described the police van where Gray’s fatal spinal injury occurred as “a casket on wheels” after Officer William Porter did not call for medical help and did not seat belt the handcuffed and shackled 25-year-old following the fourth of ultimately six stops.

Porter attorney Joe Murtha emphasized testimony from the defense team’s medical experts that called into question the conclusions reached by the state’s medical examiner’s office. Murtha repeatedly told the jury that Porter’s actions on the morning of April 12 were reasonable by department standards and in accordance with Baltimore police practice.

“I understand there is a need to hold someone accountable,” Murtha said, looking at the jury. “That is a natural human reaction . . . what is in contradiction is that Officer Porter is responsible.”

The case of Porter, 26, was sent in mid-afternoon to the 12-person jury—made up of four black women, three white women, three black men, and two white men—for deliberation. There is no timetable for how long it will take the jury to reach a verdict on the four charges against Porter, which include involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, misconduct in office, and reckless endangerment.

Expectations from legal observers in the courthouse Monday generally range from one to three days.

City officials have already expressed concerns about potential protests following the jury’s verdict.

Gray died from severe spinal injuries after suffering a broken neck at some point during a 45-minute, multi-stop ride in a police transport van last April. He was found unconscious and not breathing at the Western District police station.

At the core of the Porter case are several key questions that jurors will wrestle with:

- Did Porter fail a legal obligation—as prosecutors allege—to protect a handcuffed Gray from harm by not seat belting him in the back of a police van as department guidelines set out.

- Did Porter fail a legal obligation—as prosecutors allege—to call for emergency medical assistance when Gray requested help as Porter checked on him during several stops?

- Or, was Porter following common practice and using reasonable officer discretion by not seat belting Gray and not to radioing for medical help for Gray earlier.

One of the facts in dispute during the trial between the prosecution and defense—and again during closing arguments—has been when Gray suffered his initial injury.

Prosecutors allege Porter was “grossly indifferent” and “criminally negligent” for failing to help Gray, whom the state medical examiner testified was exhibiting signs of injury by the fourth of ultimately six stops.

Porter’s defense presented other medical experts, who testified that Gray did not suffer his broken neck until after the fifth stop—and after the last time Porter checked on Gray before reaching the police station where medical help was eventually called.

Also in dispute is an initial phone conversation between Det. Syreeta Teel, who testified that Porter told her that Gray said, “I can’t breathe,” at the fourth stop.

Porter contended on the witness stand that Teel misunderstood his remarks in the unrecorded phone conversation. Porter testified that he was referring to the first stop—before he was directly involved in the transport of Gray—not the fourth.

Former Baltimore prosecutor Debbie Hines said whether or not the jury believes Teel’s or Porter’s account of that conversation will be critical.

“[Porter] acknowledged on the witness stand that if Freddie Gray had said, ‘I can’t breathe,’ at the fourth stop then he would’ve been obligated to call for a medic,” Hines said.

Prosecutors claim Porter has changed his testimony in several instances since being interviewed by internal affairs experts last spring and taking the stand in his own defense last week, including his role in helping Gray from transport van at the Western District police station and calling for a medic.

Defense attorneys for Porter described him during the two-week trial as a caring young officer, a son of West Baltimore, who was well-intentioned, but inexperienced and ill-served by misguided police department practices and inept communication methods. The defense also repeatedly put the responsibility of securing and protecting Gray on Officer Caesar Goodson, the driver of the transport van. He is the next of the six officers to tried related to Gray’s death and faces the most serious charges of the all the officer, second-degree depraved heart murder. His trial is scheduled for the first week of January.

On Wednesday, at a press conference at police headquarters, Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake asked Baltimoreans to respond peacefully when the jury ultimately decides to convict or acquit Porter on all, some, or none of the charges. “We need everyone in our city to respect the judicial process,” Rawlings-Blake said.

On Friday, Baltimore Police Commissioner Kevin Davis cancelled departmental leave this week “as part of preparations and out of an abundance of caution” as Porter’s trial comes to an end. All sworn department personnel will be assigned to 12-hour shifts. Leave will be restored as conditions permit, according to a media release.

“The community has an expectation for us to be prepared for a variety of scenarios,” Davis said. “This cancellation is part of preparedness, just as our ongoing community collaboration efforts that were highlighted this week.”

Over the weekend, the grassroots activist group Baltimore BLOC put out a call for an “emergency protest” at 5:30 p.m. at City Hall on “the evening of and after” the Porter decision, “if Porter walks.”

“I certainly support the right of people to protest,” Baltimore NAACP chapter president Tessa Hill-Aston said after spending the day observing the proceedings. “I also hope and expect that everyone will be peaceful, not destroy any property, and not do anything that will get them locked up.”