News & Community

Ten Years Ago, Devin Allen’s Baltimore Uprising Photo Made the Cover of ‘Time,’ Launching His Singular Career

He was only the third amateur photographer to ever land the front page, but Allen didn’t care about the acclaim. What mattered was that his pictures had not been reframed to fit some pre-existing reputation of his hometown.

The demonstration at City Hall overflowed its expansive grass plaza. Protestors wearing hoodies in honor of Trayvon Martin and carrying signs that read “I Can’t Breathe”—the last words of Eric Garner—stretched to the War Memorial Building. Some of the crowd, which had marched from Gilmor Homes, dispersed after the planned rally. Others headed to Camden Yards.

“That’s where all the police were stationed to make sure we didn’t mess up the game,” recalls Devin Allen, then just a year older than Freddie Gray, the 25-year-old from West Baltimore who had succumbed to injuries suffered in police custody six days earlier.

A self-taught, independent photographer still new to documenting protests, Allen had friends who, like Gray, lived in the sprawling Gilmor public-housing complex. He, too, had once been arrested and been given a so-called “rough ride,” and he knew one of young women screaming out in the viral video of Gray’s arrest.

As protestors pushed past the ballpark’s outdoor bars, both Orioles and visiting Red Sox fans began taunting them—laughing, and throwing food and drinks.

“It became this clash of Black protestors, 17, 18 years old, early 20s, and fans calling us the N-word and monkeys—stuff these young guys never heard directed at them from white lips,” Allen says. “It was like the last drop in a bucket that overflows. Fights break out. Windows are smashed. The police cars blocking everyone in get stomped.”

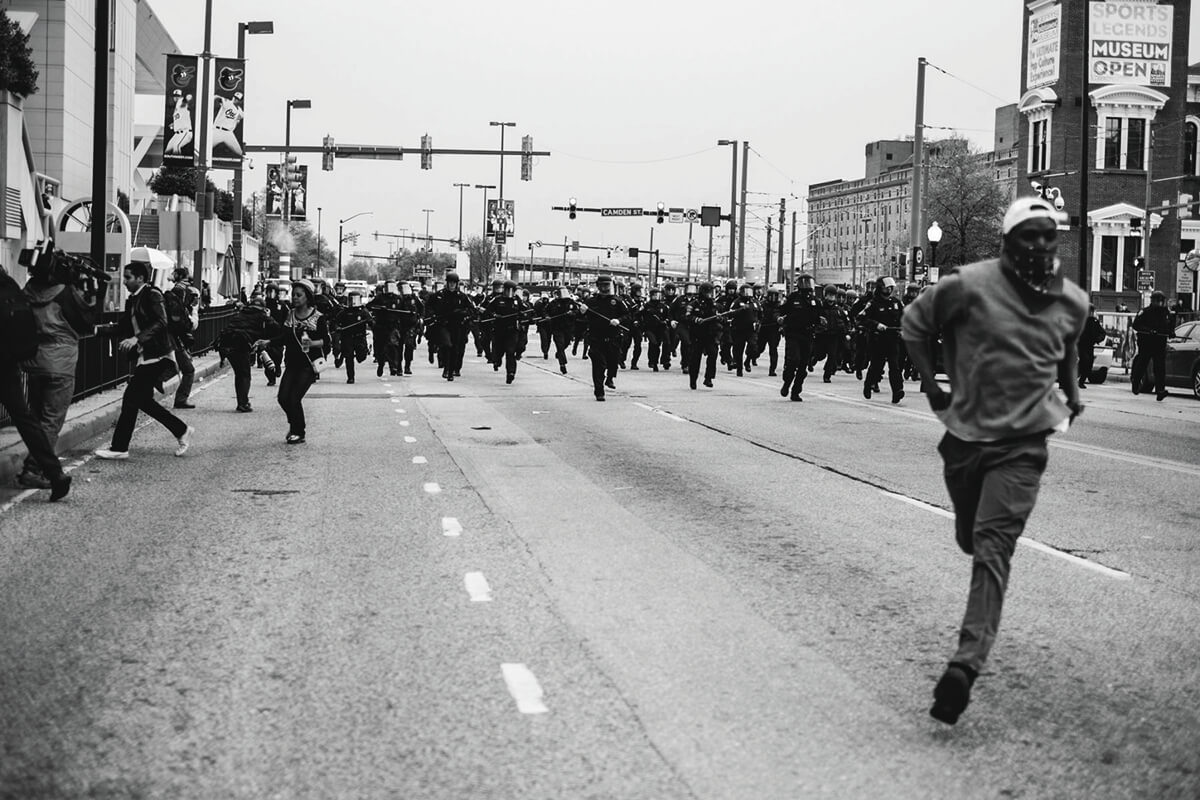

To save space on the small 8-gigabyte memory cards he could afford, Allen picked his shots. At one point, he saw a young man with a red bandana covering his face throw something at a line of riot gear-clad police.

“I was about to take a picture right then, but let him run toward me instead,” Allen says. “I’m thinking in that moment, and I’m not thinking. It’s muscle memory. It’s instinct. I snap the picture. I look down at the image and now I’ve got to go—the police are charging, and I hop over this gate.”

He’d been documenting and uploading to social media all day and posted the image to Twitter and Instagram. While everything was still unfolding, he wrote, “We are sick & tired.”

He shot until the sun went down and woke up with more than 10,000 new followers. The BBC called the next morning to interview him about police brutality and the city’s protests. Allen had been covering all the events following Gray’s arrest and subsequent death for a week. However, he chose not to photograph Gray’s funeral two days after the confrontation at Camden Yards.

“I’d lost too many friends. To me, it would’ve been disrespectful.”

Nor did Allen shoot the destruction that followed. “Photographers, TV cameras were coming to Baltimore, with everyone focused on the CVS that was burning” at the busy intersection of Pennsylvania and North avenues, he says. “I knew people in that area, and in the Mondawmin community where things started when Frederick Douglass High students got out of school that day and the system shut down their buses. I lived, and still live, five minutes away. I needed to check on my friends. I tell people I mentor that being a good photographer is sometimes about the pictures you don’t take.”

That night, Allen went to work at the group home where he helped supervise individuals with developmental disabilities. The next morning, his phone blew up with calls from a blocked number, which turned out to be Time magazine.

His photo of the young guy in the red bandana would soon be on its the cover.

“I think people forget that the protests began before Freddie Gray passed,” says Allen, reflecting on one of the most momentous events in the city’s history after a recent discussion of Black voices in the media at the Baltimore Museum of Industry. He notes that the initial demonstrations were not that large. Mostly, they involved Gray’s family and friends, people from his Sandtown-Winchester community, and others from the People’s Power Assembly gathering in front of the Western District Police Station.

“The week he died, they started getting bigger and bigger,” Allen continues. “That whole of 2015 and into the summer of 2016 was a depressing period in a lot of ways, but activists, people in the community, we dubbed it the Baltimore Uprising. That wasn’t outsiders. That was us. It didn’t become ‘the riots.’ We in the city, we wanted to shape and own our narrative and not have others do that for us, or to us.”

In fact, what made Allen most proud of his Time cover was not the affirmation of his budding talent. He was only the third amateur photographer to ever land the then-92-year-old magazine’s front page. Nor was it the money. He admittedly knew nothing of copyrights and fee scales. What mattered was that his pictures, which were also featured inside the magazine, had not been reframed to fit some pre-existing reputation of his hometown. (See: The Wire.)

“I only wanted the work—real imagery from real Baltimore, from the ground up—to get out into the world and it did.”

At the same time, as soon as the news broke on social media that an amateur West Baltimore photographer had snagged the cover of Time, professional documentary photographers and journalists started posting things like “you’ll never hear from him again” and “he’s going to disappear.” Some shared the sentiment to him face to face.

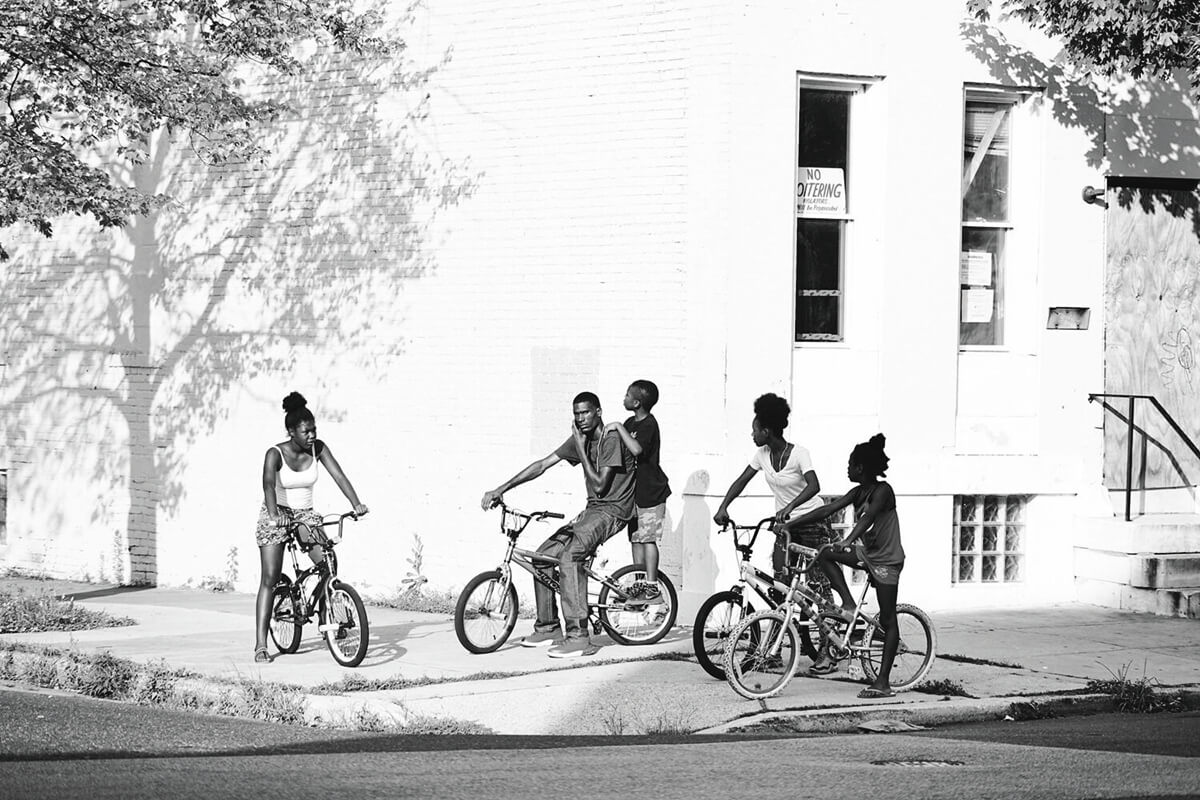

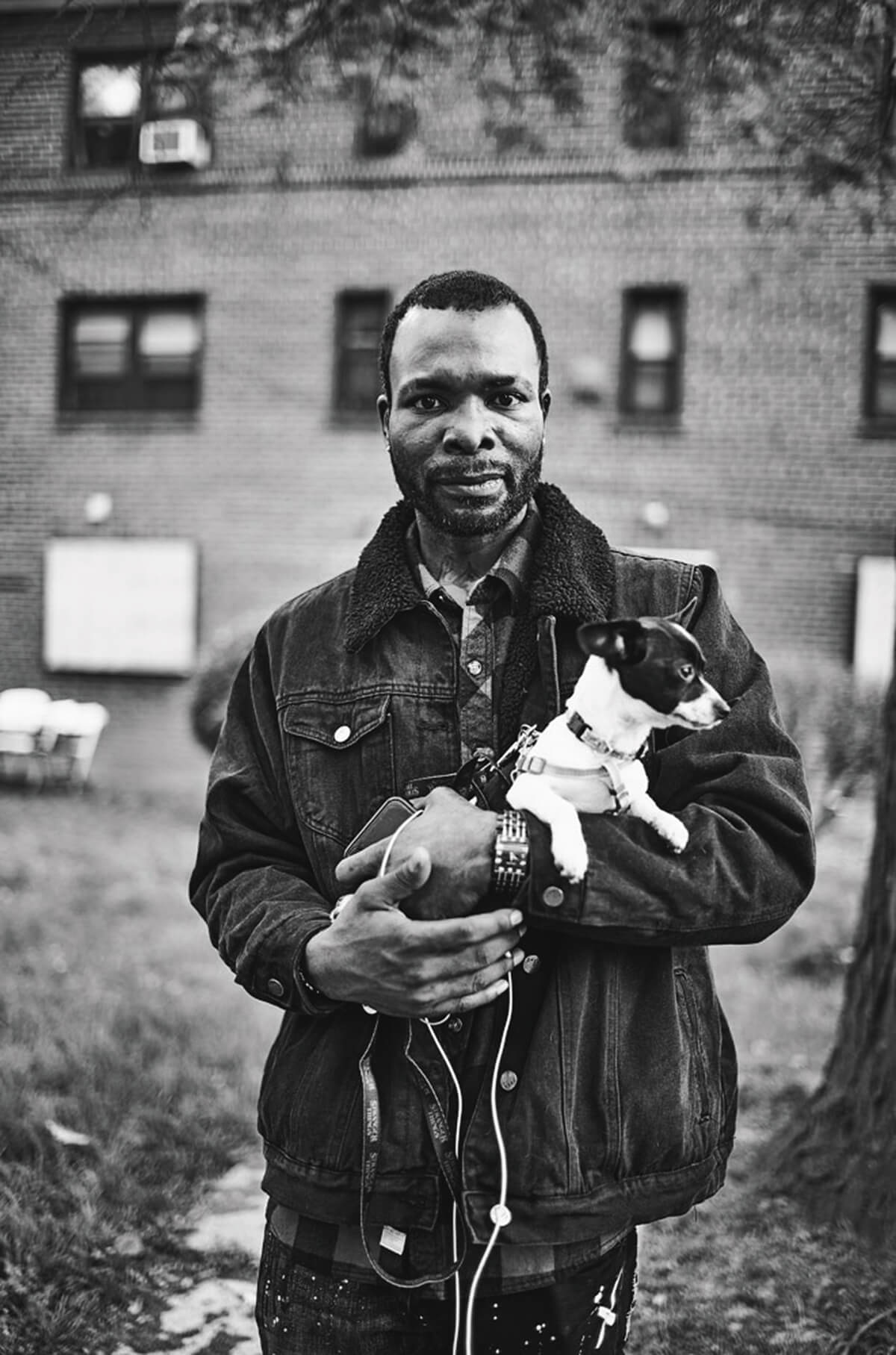

Instead, the magazine interviewed him and shared more of his photos for its LightBox blog. Allen followed that up with a Time photo essay called “The Heart of the City,” which put flesh on the Baltimore that he knew with intimate portraits from Gilmor Homes, Sandtown-Winchester, and Pennsylvania Avenue.

In July 2015, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum hosted his first solo exhibition. In August 2015, Under Armour hired him to shoot NBA star and brand ambassador Steph Curry on a trip to Asia—Allen’s first trip outside the U.S. Though he normally shoots in black-and-white, Allen switched to color for that campaign as opportunities and his photography continued to evolve. He visited Japan, China, and the Philippines, and Austria, as well, where he shot a Syrian refugee camp filled with families trying to get to Germany.

“I ONLY WANTED REAL IMAGERY FROM REAL BALTIMORE TO GET OUT INTO THE WORLD AND IT DID.”

By the end of the whirlwind year, his work had been featured in The Washington Post and The New York Times, and acquired by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, with additional exhibitions in Washington, D.C., and New York.

Along the way, he also managed to launch a youth program, giving out free cameras and teaching photography to city kids with little connection to art. And when Def Jam Recordings co-founder Russell Simmons learned of the GoFundMe page that Allen had put together to support the project, he wrote him a check for $20,000.

A singular Baltimore career was just getting started.

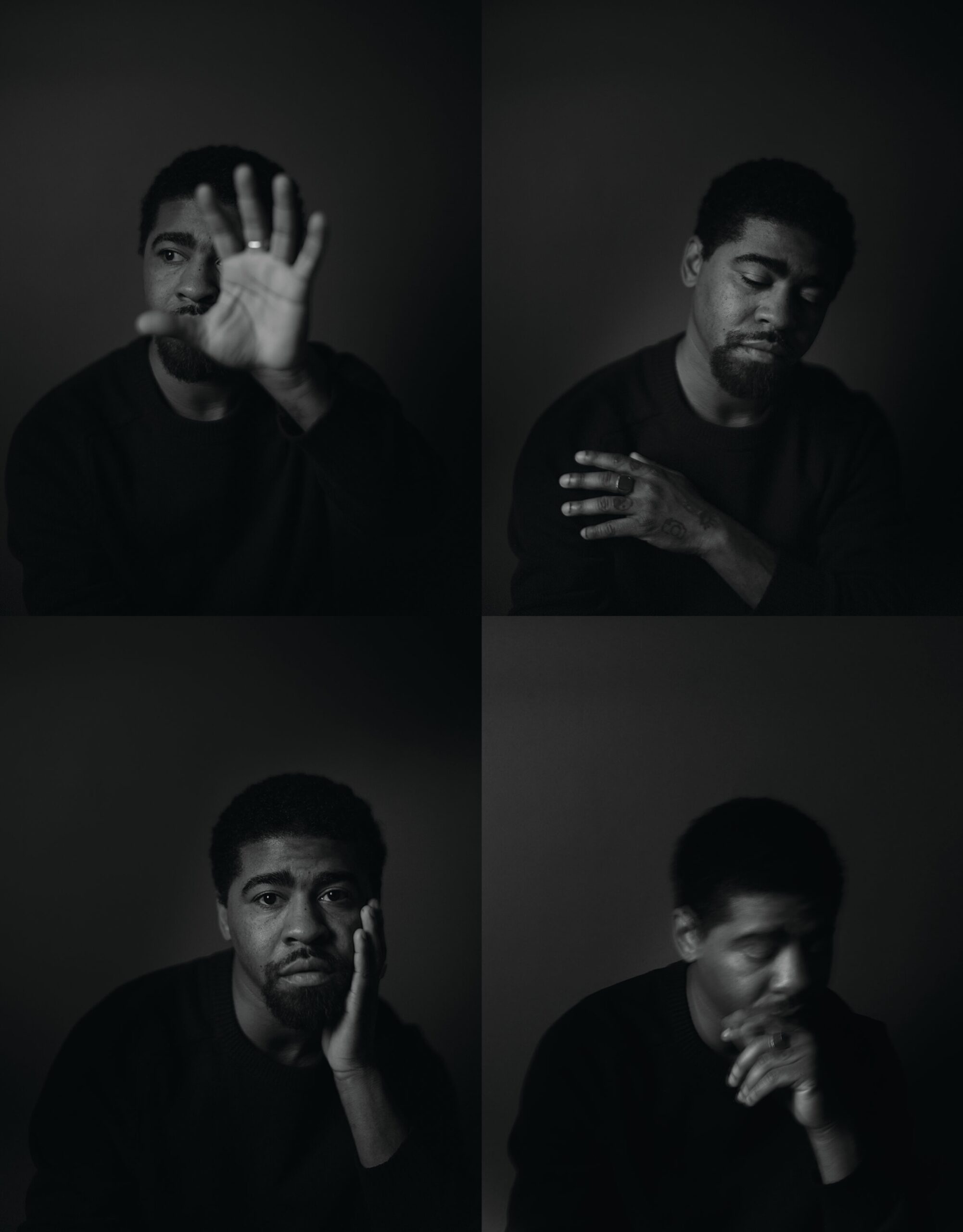

In 2017, Allen’s first hardcover book, A Beautiful Ghetto, with an introduction from his close friend, the Baltimore writer D. Watkins, was published and subsequently nominated for an NAACP Image Award. His third hardcover book, Devin Allen: Baltimore, supported through the Gordon Parks Foundation and a Steidl Book Prize grant, is due out this spring, coinciding with the 10th anniversary of the Uprising.

The collection is essentially an early retrospective of Allen’s career from Steidl, one of the most prestigious publishers of fine-art photobooks in the world. The book includes portraits, images of protests, and scenes of city street life from 2014 to 2023, including a few from Allen’s January show at Charles Street’s Galerie Myrtis, which represents him, and many never published before.

“There’s a trust and there’s a collaboration going on between Devin and his subjects,” says Peter Kunhardt Jr., executive director of the Gordon Parks Foundation, which made Allen its inaugural fellow in 2017. A self-taught photographer whose career continues to inspire Allen, Parks is considered perhaps the greatest Black photographer of the 20th century. “That’s also why Gordon Parks was so successful, because he was able to capture moments that were quite personal and complicated, and he was able to make sure that his subjects trusted him, and it’s very clear that Devin has that same skill.”

One of the projects Allen is currently working on is a series around his maternal grandmother, Doris, who let him put his first camera on her Best Buy credit card. She was, coincidentally, his first introduction into photography. The family’s informal documentarian, his grandmother had been snapping photos on Christmas morning, at Easter, during July 4th cookouts, for his entire life, always keeping a camera in her vicinity. Allen’s mother, Gail, typically wrote the captions.

Now suffering from dementia, Doris attended every show and gallery talk when his career took off. Allen, who has been renovating her home, has since come across dozens of his grandmother’s pictures, including some from her Douglass High graduation and wedding. She kept everything, he learned, including magazine and newspaper clippings of all of his work, which he found in a large Ziploc bag.

Baltimore, Allen says, is a city that can be beautiful, big-hearted, and close-knit, i.e. “Smalltimore,” and he considers himself fortunate to grow up where and when he did, and certainly with the family he had. He rode bikes as a kid, took karate lessons to be like a Ninja Turtle, and played Little League baseball.

But it’s also a city that leaves scars, and he witnessed and experienced plenty of pain and trauma as a child growing up through Baltimore’s AIDS and crack epidemics.

“I was blessed where I had a good mom, a good grandmother, an active uncle, and I had aunts in my life,” says Allen, whose disarming smile and affable nature belie the seriousness and intentionality of his work. “But that’s not the same for a lot of my peers growing up.”

He mentions a friend who lost both parents to heroin overdoses. Another who had to raise his little brothers and sisters. He estimates he’s lost 20 friends to gun violence, adding he’s had friends who have killed other friends.

“Baltimore is one of those places where sometimes you grow up with a chip on your shoulder from going through so much pain and so many trials and tribulations,” he says. People will be like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t believe a person did this and did that.’ But you don’t know what that person might have been through. That’s one of the things when you’re dealing with people like Freddie Gray [who suffered lead paint poisoning as a child] and others in the community. They got their own traumas, and during the Uprising, all that pain was released at one time.”

When he says that photography saved his life, he means it literally. Two years before the events of 2015, Allen lost his two of his closest friends to gun violence over the same weekend. One was shot seven times in front of a family member’s home. The other was killed outside of a store the next day. If Allen, who had hustled and sold drugs as a teenager and knew his way around the city’s street corners, hadn’t been shooting photographs that afternoon, he most likely would’ve been with him.

He had been shot at himself before, but after the birth of his daughter, recognized he needed to change. His mother helped him get him a job “pushing paper” at Transamerica. Not surprisingly, he found it boring, and when the life insurance company laid him off after three years, it proved a turning point.

A self-described “follower” in school, he first tried expressing himself through poetry (“I was terrible”) and spoken-word (“I hated performing”), but nonetheless found a supportive arts community in the Hollins Market district. When he later borrowed a buddy’s Nikon Coolpix point-and-shoot, he realized he’d finally found his medium (“he had to ask for it back”).

Many of the friends he grew up with didn’t understand his passion for art and dismissed his efforts to become a photographer. They told him he was too old, the window for getting into an art institute or a school like Maryland Institute College of Art had closed. Not his grandmother, however.

“The name of her series is, She Saw Me Coming,” Allen says.

ALLEN’S WORK GOES AGAINST STEREOTYPES AND CELEBRATES THE DAY-TO-DAY BLACK EXPERIENCE, AND ITS TRADITIONS AND CULTURE.

D. Watkins, the Baltimore native and New York Times bestselling author of books like The Cook Up, The Beast Side, and Black Boy Smile, knew Allen before he became a photographer, when Allen and his crew were known for throwing popular parties on the city’s west side. He says one thing that people often forget is that Allen had begun garnering social media attention in Baltimore’s Black community for his photos and portraits before the Freddie Gray protests and Time cover.

“That photograph was not some lucky, random shot,” Watkins says. “A rank amateur could not have done that. He just wasn’t published.”

Allen had sent samples of his work to The Baltimore Sun and had never gotten as much as a reply. The former City Paper had at least sent a note back when they turned his work down.

“Devin will say, ‘My career was built on the broken back of Freddie Gray.’” Watkins says. “I challenge him on that. I don’t believe that.”

To Watkins, his longtime friend’s decade-long rise in the art world has been unique and sustained, because Allen, who admittedly considered moving to New York to further his career early on, remained committed to his community.

“He’s a success in the art world, but he’s not a guy from the art world, he’s a guy from the street,” Watkins says. “He moves like how we move outside. He talks to people, he asks questions, he doesn’t project any pretension. He doesn’t think he invented the camera—he loves the skill set and he loves what he’s able to do, but he respects people more.”

Watkins adds that when an artist, filmmaker, writer, or journalist is telling stories of places of struggle or people dealing with hardship, it is always a delicate matter. Many writers and artists don’t have any accountability to those people, and some get locked into the accolades or awards they want to win.

“I’ve been to galas with Devin where you look left and you see Usher, you look right and see Chelsea Clinton, you turn around and you bump into Gayle King,” he says. “That’s not who he is or why he does what he does. I’ve seen Devin at one of the New York events on Tuesday, and Thursday he’s back in Park Heights, at Gilmor Homes, over Whitelock, in those spaces shooting pictures or talking at a middle school.”

Myrtis Bedolla is the founder of Galerie Myrtis in Station North, which has represented Allen since 2022. The mission of her gallery supports the subjects and themes of his work, she says, providing a space and platform for its social, cultural, and political concerns. In turn, his work serves as a vehicle for discourse and discussions in the Black community.

She still remembers “the rawness” of Allen’s Time cover the first time she saw it. “I think we all felt the weight of what that image portrayed given Freddie Gray’s death,” says Bedolla. “But his photography was never solely about the Uprising and protest. Sometimes we need to look through his lens and voice for things, experiences, that are a bit more complicated.”

Allen’s work goes against stereotypes and celebrates the day-to-day Black experience, and its traditions and culture, she continues.

“Those stories and that imagery are also important,” says Bedolla. “It’s also important for Black children to see themselves portrayed in those positive images, too.”

To his credit, Allen has had the city’s youth in mind since he first had the opportunity to make an impact in their lives. Over the past decade, he’s given away more than 500 cameras and has visited more schools, taught more workshops, and mentored more students than can be counted. He says most people would be surprised by the number of kids who grow up in the inner city who have few photographs, unlike he did, simply of themselves and their families.

For his exhibition titled The Textures of Us at Galerie Myrtis earlier this year, Allen invited two of his mentees to participate with him, gladly yielding the stage to them during the show’s closing reception.

Photographer Joe Giordano, a Baltimore contributor and instructor at the Baltimore School for the Arts, says he’s taught several students who received their first camera from Allen. (Giordano, who shot the Uprising for the City Paper, shares an exhibition with Allen this month at the Creative Alliance.)

“Some kids are more comfortable with their phones,” Allen says. “So, when I give them a camera, it’s just like, all right, let me show you. But what I am trying to do is help them tell their story and own their truth.

“Everything that was happening in Baltimore 10 years ago, I was able to show the honest story. When I look back at some of the headlines or how they talked about Freddie Gray or how people were calling us thugs and these other things—through my imagery, you see it in a different light. It’s about speaking up for yourself. When I’m teaching, it’s more the history of photography, the importance of Black photographers and telling Black stories, and why we need to tell these stories. The technical stuff comes on the back end.”

“It’s funny,” Watkins says of Allen and his journey. “These kids, many people in the city, they know Devin because he has been in their neighborhood, to their school. And so, when he is on television, or they follow his Instagram and see good things happen for him or the awards he receives, they root for him.

“To me, that’s the part that is special. He’s not a politician, or a bigwig businessman, or even an NBA star, and I can name 10 of those from Baltimore. His story is powerful for people. He’s the guy from the trenches that picked up a camera and made it big.”

This year we celebrate our 50th Best of Baltimore issue—our biggest and boldest yet. Subscribe before 6/20 to guarantee your copy commemorating this milestone anniversary.