Stephanie Murdock, the president of grassroots nonprofit Skatepark of Baltimore, says she thought by now, skaters from around the city would be coasting across a new skatepark in West Baltimore.

Instead, Murdock and about 30 supporters of the planned Easterwood Park skatepark, amid the wind and rain, rallied outside City Hall on Monday, demanding the city build the park as promised.

Backers of the skatepark challenged the city to explain why, after years of work to make the skatepark a reality, the city government suddenly opted in July not to build it, and instead said it would use the money to improve existing features at the park. Some went further and named state Sen. Antonio Hayes as the reason for the impasse.

“We’re going to get this park, and we’re going to get it now,” Murdock told supporters Monday.

City funding for the skatepark dates back to the fiscal year 2020 budget, which included $300,000 to study improvements to Carroll Park and examine the potential for building a small skatepark at Easterwood Park. The city earmarked $850,000 in the fiscal year 2022 budget to build Easterwood’s skatepark. Of that total, $350,000 came from city capital funds and $500,000 came from state bond money.

However, in July, the city’s Department of Recreation & Parks called community activists Murdock and Marvin “Doc” Cheatham into a meeting. During the meeting, backers say they were ambushed with news that the city no longer intended to build the skatepark.

Nevertheless, skatepark supporters say they’ll continue to fight to build the park. Activists framed the issue as one of racial equity. Baltimore has three public skateparks, they say, but none are located in Black neighborhoods.

Chrissy “Sosii” Brown, a skateboarder from Ashburton, says building the park in Easterwood gives Black skateboarders easier access to a sport that they regularly travel long distances and negotiate risky situations to participate in.

“This is the plight of the Black skater, having to take risks just to skate,” Brown says, “having to travel long distance by foot, board, or public transportation just to skate…having nowhere to skate in our own neighborhoods.”

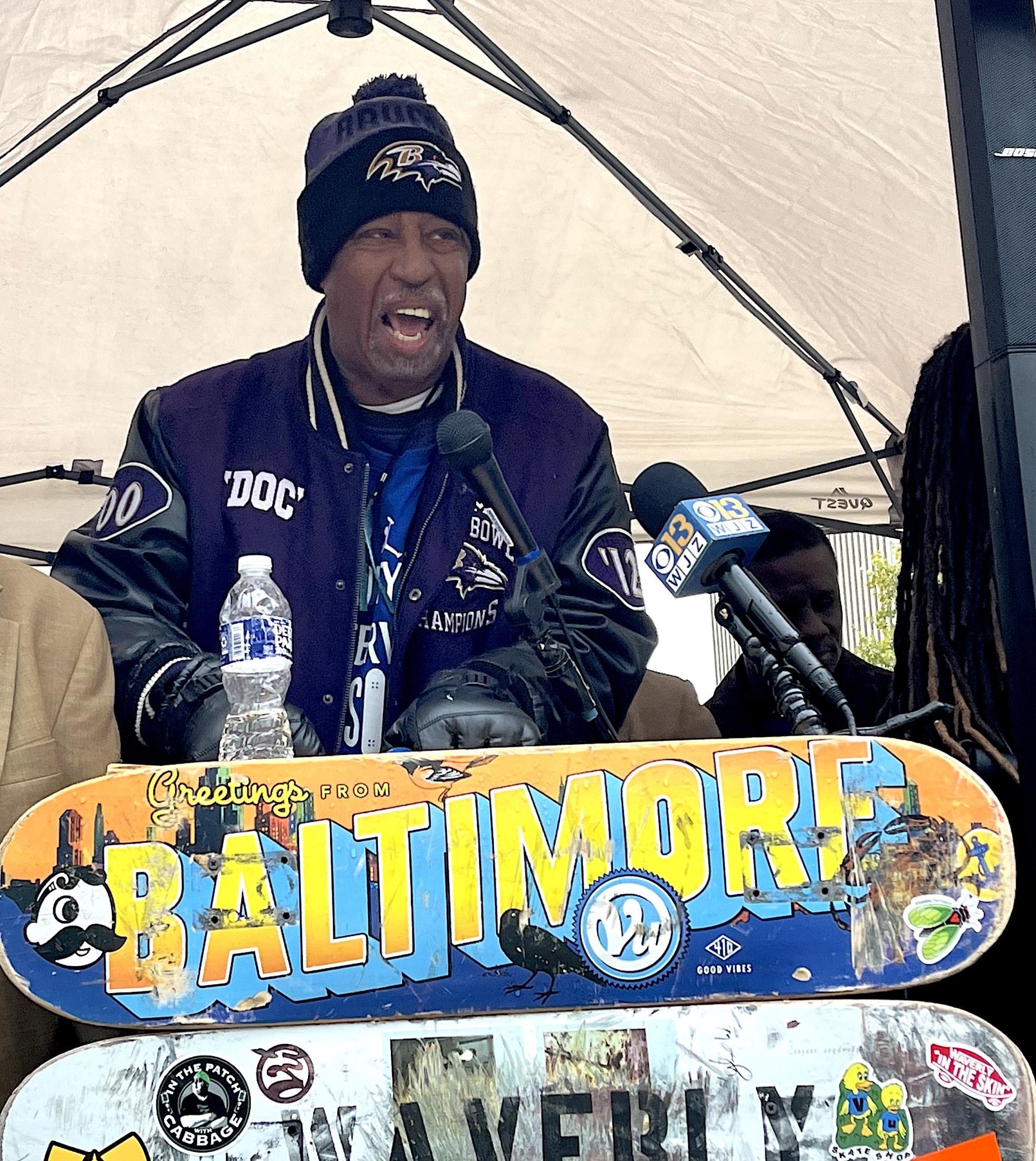

Cheatham says he started pursuing building a skatepark in West Baltimore about eight years ago at the behest of kids from Easterwood. He says those kids wanted the skatepark so that they didn’t have to travel outside of their community to skate.

After years of work, Cheatham told the rally, halting as he became emotional, he felt particularly blindsided by the city’s sudden opposition. He says that, initially, it wasn’t skatepark backers’ idea to build the park in Easterwood. They chose the park at the behest of the Department of Recreation & Parks.

Consequently, Cheatham blames Hayes for pressuring the city into abandoning plans for the skatepark.

“I’m saying the city has to reconsider the injustice that they’re doing. If not, recall Antonio Hayes,” Cheatham says about the senator who is running for re-election next month. “Because he’s the culprit in all of this.”

In June 2019, Hayes signed a letter praising the project and urged the city to financially back the construction of the skatepark in Easterwood.

“We are requesting the support and assistance of the Skatepark of Baltimore to provide a desperately needed and comparable recreational option to youth and young adults in this West Baltimore neighborhood,” Hayes writes in the letter, which was provided to Baltimore by skatepark supporters.

Skateboard activists are unsure why Hayes is now working against the project, but some at the rally said his motive is retribution for Cheatham’s persistent criticisms.

In a telephone interview Monday evening, Hayes said he previously told supporters the city isn’t abandoning plans to build the skatepark altogether. Still, he says, the surrounding community prefers repairing Easterwood’s playground, building a walking trail, and maintaining the park’s basketball courts instead of building a skatepark.

Hayes also insisted surrounding communities decided to nix skatepark construction. No one who lives around Easterwood Park, he says, supports building the skatepark. If skatepark backers were given 24 hours, he says, they couldn’t find 10 supporters who live within two blocks of the park.

“This is something Doc has created in his head that the community wants as a matter of equity,” Hayes says.

Despite the city altering plans to upgrade Easterwood without a skatepark, that course of action isn’t sure. Any attempt to use the funds for park improvements without a skatepark faces the potential for a protracted fight throughout the bureaucratic process to reallocate money intended for the skatepark.

The Department of Recreation & Parks can’t arbitrarily use money earmarked for the skatepark, says Murdock, a city employee who previously worked for Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke. To reallocate those funds, the Department of Planning would first have to sign off on the change. The Board Estimates, which consists of the mayor, city council president, comptroller, city solicitor, and the director of public works, would then need to grant final approval to reallocate the skatepark money.

That process grants skatepark supporters time to flex their political muscles and potentially garner enough support to convince the city to build a skatepark in Easterwood again.

“I told my neighborhood two weeks ago I would give my life for this skatepark,” Cheatham says.