News & Community

Ellen Frost is Changing Baltimore, One Bloom at a Time

Frost's Waverly shop Local Color Flowers is known for the community it fosters, and its commitment to the first and last words of its name.

It’s the Wednesday after Mother’s Day and Ellen Frost is still coming down from her busiest week of the year. Just days ago, thousands upon thousands of flowers filled the walk-in cooler of her Brentwood Avenue workshop in Waverly. Floor to ceiling, there were buckets of bright pink peonies and dusty blue delphiniums, peachy ranunculus and black-and-white anemones, as well as the season’s first foxglove and very last tulips—a reminder that there would only be 30-some days left of spring.

“Those are Laura Beth’s—they’re out of control,” says Frost, leaning back in a white swivel chair, tipping her head toward hot-pink snapdragons from Laura Beth Resnick’s Butterbee Farm in White Hall, their stems stretching some three feet tall.

For now, the smell of eucalyptus wafts around the 2,000-square-foot flower shop, floral design studio, and unofficial community living room, with its white cinder-block walls and vase-stacked shelves, while Frost’s designers leisurely finish arrangements for tomorrow’s deliveries.

But in a few short hours, the buzz will begin all over again, when dozens of neighbors, friends, and strangers wander in to make their own bouquets during the weekly Flower Happy Hour, as they will on Saturday, too, when the garage doors open to folks on their way to the 32nd Street Farmers Market, as well as Sunday, during one of the weekend’s three design classes.

They all flock to Local Color Flowers—or LoCoFlo, as it’s affectionately known—for its kaleidoscope of color, the community it fosters, and its commitment to the first and last words of its name: Every single petal in this place was grown within just 100 miles of Baltimore.

“In the beginning, everyone thought we were crazy, like this is a terrible idea, it will fail, it will never work,” says Frost. “And we were like . . . why not?”

Fifteen years ago, the floral industry looked quite different than it does today—not just across the Mid-Atlantic, but the entire country. For starters, the scene was much smaller. Following the 2008 financial crisis, the number of independent florists dramatically declined, and those who remained relied heavily on the global wholesale market to import flowers from overseas year-round.

Meanwhile, a handful of American farmers sold their seasonal harvests mostly at local farmers markets, which is exactly where Frost first encountered them, in Towson, in the early 2000s. In due time, this discovery would lead her to become one of the founders of the national “slow flower” movement, and the de facto floral godmother of Baltimore, working with some 200,000 local blooms each year. Though she’ll be the first to tell you, she couldn’t have seen it coming.

For the first half of Frost’s life, “I had no interest in flowers,” says the 50-year-old native of Buffalo, New York, who has a sharp wit, cheeky smile, and bouncy blonde curls.

“I remember my grandmother had peonies in her backyard—and that they would bloom when school got out, with the lilacs—but nothing else.”

In their Irish-American neighborhood, Frost’s mother worked at the local Department of Parks and Recreation, while her father ushered at the Bills football stadium between shifts at Bethlehem Steel. Observing her tightly run business today, it’s easy to see tethers to the blue-collar work ethic that she was raised on, but back then, she dreamed of becoming a politician, maybe even president one day.

In college, she studied political science, and after graduation, she entered the Jesuit Volunteer Corps—“like The Real World, for Catholics,” quips Frost—where she met her husband, Eric Moller.

“He was sunburnt from head to toe,” she says wryly, “but I remember thinking, hmm, Eric—he’s interesting.”

The couple shared the same dry sense of humor and penchant for community service, and they soon ended up in San Francisco, where they started nonprofit careers, before moving to Baltimore to be closer to Moller’s family in 1999.

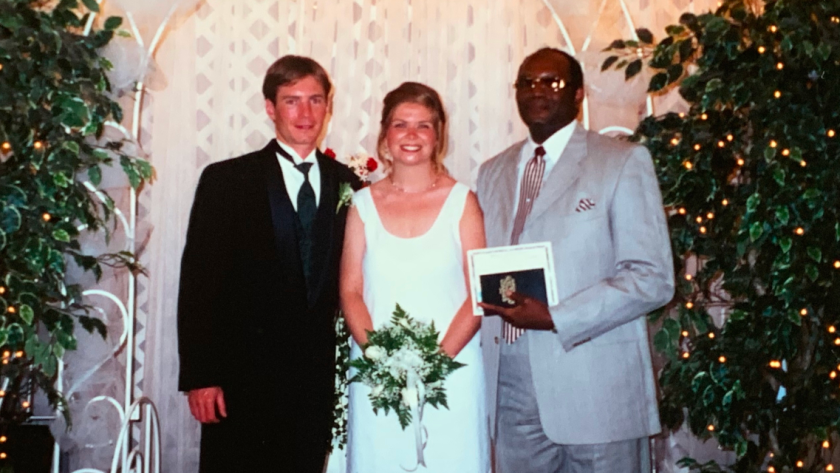

The next year, they eloped to the Silver Bell Wedding Chapel in Las Vegas, and Frost still finds herself in stitches at the thought of their 10-minute time slot.

“Elvis was $75 and we were too broke to afford him,” she says through laughter and tears, recalling a rented plastic bouquet. “Clearly, even then, I had no connection to flowers.”

But that would change in Baltimore. Here, Frost found another nonprofit job, but was in search of something more than a nine-to-five. Living in Butchers Hill, she reconnected with an old Buffalo acquaintance, who introduced her to his then-girlfriend, Marina Merrick. The two women hit it off immediately, both in their late 20s, with socially conscious points of view, and they soon spent all their free time with one another—going on jogs, tending to each other’s gardens, cooking meals with their partners.

“Marina was the opposite of me, she grew up in California, her mom was a hippie, she’s super creative,” says Frost, also noting Merrick’s green thumb. “Back then, we were so young, life was so slow, we had so much time to explore things.”

Which is how Merrick thinks back on it, too. “I can’t remember not being friends,” she says. “We did everything together.”

LOCAL COLOR FLOWERS IS KNOWN FOR ITS COMMITMENT TO THE FIRST AND LAST WORDS OF ITS NAME: EVERY SINGLE PETAL WAS GROWN WITHIN 100 MILES OF BALTIMORE.

Through their friendship, Frost became enchanted by the magic of growing things. In 2004, they signed up for the University of Maryland’s Master Gardener Program, and within months, she had a new side gig, working at Glen Arm’s Breidenbaugh Farms and selling their vegetables at the Towson Farmers Market, where Merrick already worked. There, she had a chance to meet not just customers but farmers, like John McKeown of Locust Point Flowers in Cecil County.

“He was the first person I knew who grew flowers for a living,” says Frost, “and really the impetus for everything that came after.”

That fall, Merrick enlisted McKeown to provide the pink, red, and yellow dahlias for her wedding. But she also called on her friends to make the bouquets—in a way, the very first Local Color Flowers.

“It was my best friends, the best flowers, grown by a guy we all loved, that everybody loved at the wedding,” says Frost. “I mean, nobody ever responded to lettuce that way . . . But the whole experience—I was just like, This! I want to do this again.”

At that time, she was getting her graduate degree at Loyola University, where an entrepreneurship class introduced her to the idea of starting her own business—a concept that had never crossed her mind growing up in a town of factory workers, firefighters, and teachers. But it all came together after learning about the good, bad, and ugly of the global floral industry through Flower Confidential by Amy Stewart.

The 2007 book laid it all out: At the grocery store, a conventional bouquet often costs less than $10, and that’s because 80 percent of the flowers sold in the U.S. are now imported from other countries like Colombia, where cheap labor and trade subsidies yield cut-rate prices. It’s an economy of scale, where mass quantities of flowers are grown with chemicals, wrapped in plastic, and then shipped—in refrigeration—across thousands of miles, with an environmental footprint that emits some 360,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere on Valentine’s Day alone each year.

But Frost also read the story of the Bonnie Doon Garden Company in California, which only used local, seasonal, sustainable flowers—“all interesting, unusual, old-fashioned, ephemeral, perfumey, not-your-typical-florist kind of flowers,” wrote Stewart—the kind that Frost had come to know herself through McKeown. The difference is immeasurable, like eating an heirloom tomato straight from a Maryland garden in summertime versus a beefsteak grown in Mexico come winter.

Frost has a clear memory: “Marina and I walked to yoga in Fells Point, talked about the book, had to sit through the whole class quietly, but then right after, were like, ‘Oh my God, we should definitely do this!’”

With a third friend, Jen Bryant, they cofounded Local Color Flowers in 2008, at a time when there was no middleman between local farmers and local florists in Maryland, hoping to serve as a farm-to-table bridge between the two, for wedding clients, in particular. Still juggling day jobs, they worked out of each other’s kitchens, then eventually a spare room in Mt. Vernon, then a garage behind Red Fish Liquors in Hampden. With few examples to follow, they borrowed books from the Enoch Pratt library and took design courses at Baltimore City Community College.

“Back then, you couldn’t just Google ‘local flowers,’” says Frost, compared to today, when that hashtag yields 600,000-plus hits on social media, and celebrities like Floret Flower Farm’s Erin Benzakein have one million followers and a TV show. “Even still, it didn’t seem impossible, or weird, or stupid. There was no model. So we built our business around the flowers.”

Back then, the women only knew three flower farmers—McKeown, plus the late Mel Heath of Bridge Farm Nursery in Cockeysville, whose grew legendary peonies and hydrangeas, and Bill Harlan of Belvedere Farm in Fallston, whose diverse offerings still range from daffodils to chrysanthemums. But those men connected them to the Maryland Cut Flowers Growers Association, a group of Mid-Atlantic farmers and gardeners who could help meet their demand, like Bob Wollam of Wollam Gardens in Virginia, who Frost used to stake out around D.C. in order to buy his blooms, which LoCoFlo still purchases today.

That first year, they had eight wedding clients. “Strangers!” exclaims Frost, as opposed to their first few, who were strictly friends. Their arrangements fit the company’s name, featuring bright pops of coral, or magenta, or fuchsia, which seemed to scream April, or October, or whatever month it happened to be—always the designer’s choice and based on what was local.

“In the beginning, I was much more nervous about those discussions,” says Frost, recalling one early request for spring calla lilies in a September wedding. “It was so stressful that I thought, you know what, every other florist in the world will do that; we’re not the ones. And over the years, I’ve gotten much more comfortable saying that. If you’re into what we do, that’s cool. And if you’re not, that’s cool, too!”

“IT DIDN’T SEEM IMPOSSIBLE…WE BUILT OUR BUSINESS AROUND THE FLOWERS.”

But people were into it. In their second year, they had 22 weddings, and the next, 36. By this time, Bryant had left the business to start a family, and before long, Merrick moved to the Eastern Shore. Now on her own, Frost quit her job and went full-time with LoCoFlo in 2011, with Moller joining the following year.

“It was a scary time, like can I really do this?” she says. “And it took me awhile to figure out: I think I can.”

Merrick thought so, too: “Ellen never gives up. She’s not afraid to take risks. . . . I mean, she’s tough, she’s from South Buffalo, but she genuinely cares, and wants to make people happy. She was always the one who got emotional seeing brides get their bouquet.”

But to complicate matters further, many of Frost’s early farmers were beginning to age out, leaving her with an uncertain supply chain. Quickly, she focused on recruiting younger growers, attending farmers markets and Farm Alliance meetings to convince them to consider flowers. Which worked.

“I met Ellen, and she was like, ‘I’ll buy anything you grow!’” says Maya Kosok of Hillen Homestead, and also founder of the Farm Alliance, who now cultivates more than 80 flower varieties near Clifton Park. “That first season, in 2013, she took whatever I had, no questions asked. It cemented for me that flowers were viable.”

Resnick of Butterbee Farm had a similar experience. She met Frost for her sister’s wedding consultation, and within the year, the vegetable grower was harvesting her first flowers. At first, she sold LoCoFlo sporadic stems of this or that, but this past Mother’s Day, her deliveries included just over 2,000 blooms—poppies, orlaya, godetia, dusty miller—while Kosok dropped off bucketloads of baptisia, bells of Ireland, and dianthus.

“We can all agree that Ellen singlehandedly created a flower farming boom in the Baltimore region,” says Resnick, who Frost also inspired to start farming in winter, and she now operates three 150-foot heated greenhouses across five acres in Baltimore County. “Now that I know what I do about this industry, I cannot believe the lengths that she went to encourage us. She’s been a gift to this community. I hope she feels as loved she is.”

Today, there are more than 100 flower farms in the state of Maryland, including at least 25 in the Baltimore area, and Frost works directly with about 40 of them. But she does more than that—connecting newcomers with established growers, as well as providing information and inspiration for other florists and businesses interested in local blooms.

“She’s not a gatekeeper,” says Allie Smith of Bramble Baking Co., who hosted her first flowery cake pop-ups at LoCoFlo in 2017. “She’s really a cheerleader for this entire ecosystem.”

For Frost, the more the merrier, when it comes to supporting local. She credits this ethos to McKeown and the other old-school farmers who shared so much of their time, knowledge, and wisdom in the early days—taking her into their field, showing her how to harvest, sharing the best ways to extend a flower’s vase life—and she calls their obsessive labors of love “infectious,” then and now.

“These guys just opened themselves up to us, there were no secrets, they told us everything,” she says. “And so to reciprocate to new growers or florists just felt right. People were generous with us. And we were generous back.”

That’s a tangible feeling in the shop these days—the former horse stable turned potato chip factory turned car radio dealer turned antique store turned flower studio. Frost bought the building a decade ago, and more recently, commissioned her designer, Jess Valmas, to paint its vibrant front mural, featuring larger-than-life black-eyed Susans and one supersized praying mantis.

On any given day of the week, this space is home to not only an abundance of blooms, but also classes, book clubs, trivia nights, and the beloved Bloom Battle design competition, all offered for both the flower fanatic and the casual passerby alike, in an attempt to welcome everyone.

When the garage doors open, you can purchase a flower for as little as $3, or even just stop to smell the roses—literally—grown by Lauren Uhlig of FlorXEight in Hamilton.

For Frost, there’s something extra special about watching those thorny stems rise from the concrete streets of Baltimore, a city she now roots for as much as Buffalo. In an especially local moment, she once gifted John Waters a bouquet of milkweed known as “hairy balls,” which he later thanked her for via postcard, calling them both “beautiful + rude.” Maybe it’s all a metaphor: Look what can grow here, boldly, with enough attention and care.

“You go to business school and you’re taught, ‘Grow, get bigger, make more money!’—but that was not the right fit for us,” says Frost, who now takes on about 30 wedding clients a year, compared to 120 in 2016. “We are constantly evaluating how we can best serve our community. The flowers are just the tool to connect people.”

And even if it means smaller profit margins, she’s adamant about paying her people, both florists and farmers, a living wage, which always means charging what the flowers are worth.

Take Hillen Homestead, for instance. By contrast to overseas flower farms, it’s located less than two miles from LoCoFlo, where, on once-vacant lots, Kosok uses sustainable farming practices, abstains from chemical pesticides and fertilizers, and shares seeds with her neighbors. She has keys to Frost’s shop and drops off her fresh-cut harvests throughout the week, which then often head to customers the next day.

“The value of keeping dollars in our local economy is not to be underestimated, and when Ellen spends $1,000 with me, that’s money I’m going to pay a neighborhood handyman or use to buy my crew lunch from the restaurant down the street,” says Kosok. “There are lots of florists who have approached me like, ‘Oh, we love local,’ but she really walks the walk, and puts her money where her mouth is. . . . I meet farmers all the time who are like, ‘I wish I had an Ellen in my city.’”

And it’s not all business. Frost and her colleagues have all become close friends, exchanging emoji-laden text chains, attending each other’s celebrations, and starting business clubs together.

“I’m always like, ‘My boss, I mean my friend, I mean my boss-friend,’” says designer Brittany Baltimore (yes, Baltimore!), who threw her daughter’s first birthday party at LoCoFlo.

“And Eric softens the edges—even though he’d be like, ‘No, I’m the tough guy!’” laughs Valmas, whose own Bloomhouse flower farm in Parkton has received significant support from Frost—in fact, it just took over the subscription delivery portion of LoCoFlo’s business.“Whenever we’re stressed, Ellen reminds us, they’re just flowers. It’s good no matter what.”

Of course, this work isn’t just playing with petals all day. It’s fast-paced, with long hours and lots of physical labor, and after the coronavirus pandemic’s pause for reflection, Frost is now dreaming up new ways to spread the slow-flower gospel with the greater world. She’s ramping up her newsletter, offering more online classes, and considering national speaking events, with her name being highly respected throughout the industry, though she’s careful not to preach.

“People just don’t know that much about flowers, but I know some who couldn’t name one five years ago and now come to me like, ‘Isn’t it tuberose week?’” she says. “That’s why we do this.”

And so LoCoFlo is always top of mind. Frost and Moller live in nearby Lake Walker, just 10 minutes from the studio, and and they often talk shop outside of it, which is fine by them. “We love what we do,” she says, matter-of-factly.

Her husband is the jack-of-all-trades (his company alias is “Floral Batman”), handling behind-the-scenes tasks like bookkeeping, the website, and other odd jobs, from cleaning buckets to unloading compost. “And thank God,” says Frost, “because there would be no business without that.”

Each January, the couple takes a “company retreat,” aka vacation in Florida, and on their Mondays and Tuesdays off, they make time to hike Lake Roland or bike the NCR Trail. “That’s where I’m the boss,” says Moller. “Afterwards, we get doughnuts at Wegman’s.”

At the end of May, he was off the hook from buying her a bouquet for their 23rd wedding anniversary, because even after spending all day surrounded by stems, Frost still can’t help but some home for herself. Peonies currently sit on the desk in her home office, and two decades in, the former black thumb admits that the flowers have officially won her over.

“More than I ever would have imagined,” she says.

A few years ago, the Association of Specialty Cut Flower Growers recognized her with an award for being a pioneer in her field, and when asked how that sort of title makes her feel, Frost offers one word:

“Old,” she says with a smirk. “Maybe we were the first in some ways. But a lot of people helped us get here.”