News & Community

Essay: How I Learned to Care for a Plant That Long Cared for Me

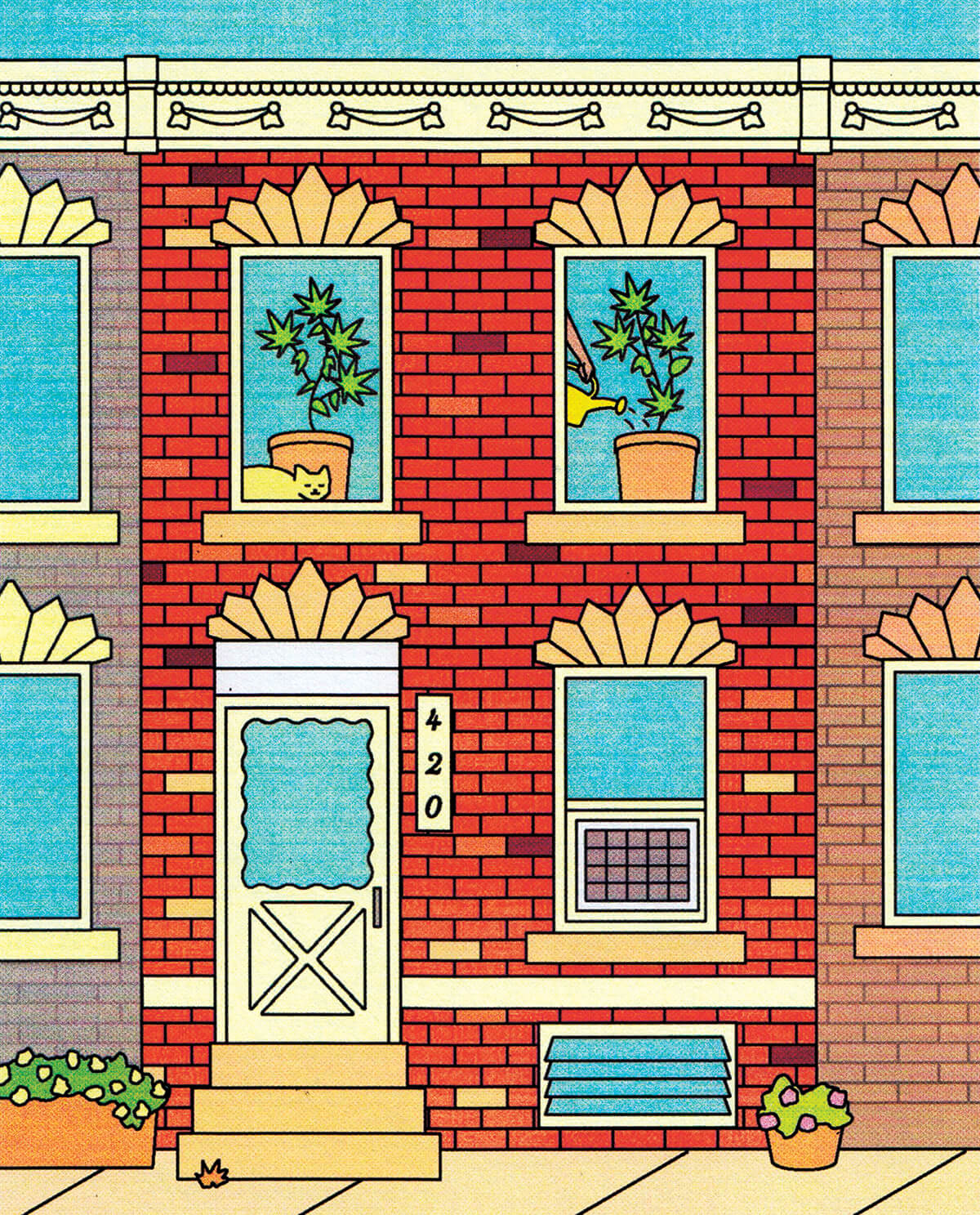

A local journalist (and stoner) attempts to subvert corporate cannabis.

One fine morning last summer, as I walked out onto the second-story back deck of my rowhouse, I basked in the sun gloriously hitting the leaves of my new cannabis plants. I burned a spliff, began trimming some leaves, and saw a neighbor working below in her garden, too. I noticed the birds chirping, as they do that time of day, and heard the horses from the nearby arabbers’ stable clomping through the alley.

Then I heard another familiar sound, that of Foxtrot, the Baltimore Police Department’s helicopter, warbling overhead, and for a moment my mind went back to the old days and the fear of jailtime over the cultivation of a plant.

Getting to this point was something of a personal journey—an awakening even. This story is about how I got there.

The first time I saw cannabis plants growing, they were underground. Not just in a metaphorical sense, but literally, in a secret room dug beneath the floor of a friend’s closet. Today, everything is different. Not only did Foxtrot evince no interest in my horticultural activities, the police union has argued that cops shouldn’t be randomly drug-tested for the same weed over which they once destroyed people’s lives.

In criminal terms, if you grew cannabis, it was called “manufacturing marijuana”—a felony with a potential 20-year sentence. But the phrase contained a fundamental flaw in law enforcement thinking. You don’t manufacture weed. It’s a plant. You tend it.

In the rush of legalization, for both the Big Weed big shots and the typical consumer buying dispensary gummies, manufacturing is perhaps the right word to sum up our new era of legal cannabis, however.

Massive grow operations and industrial processing facilities convert raw cannabis flower into highly specialized products that would have boggled the minds of my grower friends in the 1990s. Multistate operators dominate most markets to the point it can be difficult to know who owns a given dispensary or produces a given product. Weed has gone corporate.

Don’t get me wrong. I got a medical card as soon as I could, switching from my “man” to the legal stuff for the variety, legitimacy, and safety of the dispensary. I loved that the terpenes—the chemical compounds that give the plant (and all plants) their odors, flavors, and medicinal effects—were listed alongside THC levels on labels. Knowing exactly how much THC is in your edible is a huge improvement over the pot brownies of yore. I also loved the access to safe vapes. (I would’ve quit cigarettes years earlier if they’d been available.)

For a long time, I loved this manufactured cannabis, and I’m not the only one. Between July 1, when the law that allows adults to buy cannabis for recreational purposes went into effect, and the end of 2023, dispensaries in Maryland sold 56,510,028 grams of cannabis flower—that’s 56,510 kilos or 124,583 pounds. And that doesn’t even count edibles (nearly 3 million sold), concentrates, vapes, hash or any of the other forms of THC that Marylanders can legally purchase.

Overall, it equated to nearly $800 million in revenue in just six months for a start-up industry already employing more than 5,000 people in the state’s 96 legal dispensaries, 18 legal grow rooms, and 23 legal processing facilities.

But, as we approach the first anniversary of adult-use legalization, problems with corporate cannabis are also becoming more apparent. There is, for example, still just one fully Black-owned dispensary in the state, Mary & Main, in Prince George’s County. In Baltimore City, there are no dispensaries west of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

The initial effort to create a more equitable distribution of licenses—in part to address the disproportionate damage of the drug war—was stalled when Curio Wellness, one of the area’s biggest cannabis companies, sued because it believed the new licenses would hurt its market share.

The Curio lawsuit brought to light that David Smith, the conservative Sinclair Broadcast Group executive chairman who recently bought The Baltimore Sun, was one of the company’s major investors. A cash-ready investment ability gives a significant advantage to the well-heeled, thanks to the continuing federal cannabis prohibition, which makes banks leery of writing loans to cannabis businesses. The prohibition seems almost designed to give the industry away, state-by-state, to the rich.

But that’s not the only deleterious effect federal prohibition has on the industry. Because debit and credit cards can’t be accepted—the banking issue, again—it’s an entirely cash operation, making it extremely dangerous for businesses. As a result, the state lists 32 “ancillary” cannabis businesses, most of which are security companies, often run, ironically, by ex-police officers.

Then, there is just so much marketing. The New York Times recently profiled the cannabis “lifestyle” products brand, Cookies, which has a franchise in South Baltimore. It would seem that one of the keys to success in the industry is branding, something that has become increasingly evident. What had once been a fun trip to the dispensary now feels like a sensory bombardment akin to walking down the cereal aisle in a neon grocery store. Another bummer: first having to place your order online. Like Amazon.

Eventually, I realized I wanted to make my weed analog again.

IN CRIMINAL TERMS, IF YOU GREW CANNABIS, IT WAS CALLED “MANUFACTURING MARIJUANA.” BUT YOU DON’T MANUFACTURE WEED. IT’S A PLANT. YOU TEND IT.

I trusted my former underground source, who we’ll call Kurt V., more than the cannabis companies. Kurt, who is white, worked in the black market for years, developing a network of small-time, organic, and minority growers. He has since crossed over into the legal industry in various capacities, but he has a lot of thoughts on corporate cannabis, which he describes as a toxic mixture of mass consolidation, where “big fish get bigger,” and “the wildest West,” where each state repeats the mistakes that have been made elsewhere.

“It’s mind-boggling to me how much money is in the industry and how much of it is fly by the seat of your pants,” he says.

A big divide is cultural. “The ethos or the philosophy of the cannabis CEO is not the same [as a local grower],” Kurt says. “I’m gonna sound like a dirty hippie here for a minute but…there’s a relationship to the plant that these new people don’t have. I’m talking about the ‘lovey-dovey’ kind of like. This is plant medicine. You know, this is sacred.”

As he spoke, I felt guilty about abandoning him for the corporate stuff. But he was articulating exactly why I had returned and why I was interested in starting to grow myself.

Ras. Langford “Crucial” Johnson, a Black Rastafarian who has been growing cannabis in Baltimore since the 1990s and worked in some of the first medical dispensaries in the city, recently applied for micro-grow and dispensary licenses. He has a more positive view of the above-ground industry.

Unlike the first, exorbitant state licenses, Crucial says his team paid a $1,000 fee for the micro-grow license and $5,000 for the regular license through the Maryland Cannabis Administration and its newly formed Office of Social Equity.

Such licensees must show that they are part of a community disproportionately impacted by the drug war. If the application passes, it still goes through a lottery. But he is confident in his application and his team.

Crucial also carries a relationship with the plant that goes deeper than simply developing a profit oriented operation.

“My whole goal is to bring the culture forward,” he says. “I grew up on a farm in southern Maryland. So farming is part of my culture, my background. That’s who I am as a person.”

Since I’d already returned to my underground network for my flower, I decided it was time to get some rooted clippings from a mature plant and grow a couple of plants in pots on my back patio—not unlike buying tomato plants at the greenhouse.

Under Maryland’s adult use cannabis law, adults over 21 can grow two plants and medical patients can grow four plants. I still have my medical card. I was looking for four clippings.

One day, Kurt and I drove up to the house of his friend whose indoor grow-room had supplied a fair amount of the weed that I’d bought from Kurt over the years. It resembled the X-Files set-up I’d seen in the underground lair years earlier. Lights, fans, reflective material.

The guy I’ll call the Farmer had eight or so clippings and told me and Kurt to each take two. One was Cindy 99, a sativa, and the other an indica hybrid strain called White Widow. That’s one thing about legalization, the genetics have exploded. The number of strains is mind-boggling.

Sativas, which come from Central Asia, tend to grow tall and skinny. Indicas, from the Middle East, short and bushy. I was happy to have one of each to compare. The Farmer asked if I was going to do indoor. I shook my head no.

For some people, indoor is a good option. Crucial noted the cost of indoor growing equipment has fallen dramatically. He recently set up a grow-room with LED lights, a tent, fans, and the pots for $350. Previously, with even cheap LEDs, the lighting alone would have cost that much.

“If you don’t have children, it’s a good practice because they’re just like kids,” Crucial says of indoor plants. “They want what they want when they want it, and you can’t always go away. You have to have a babysitter.”

But “if you do outdoors,” he says, “you can do whatever.”

“You can do whatever” was more of my stoner speed. It’s best to be able to grow outdoor plants in the earth itself because the roots will have more room to spread out and the plants can get bigger, but my backyard is very shady and wouldn’t allow for enough light. However, I do have a small, south-facing back deck that gets great light and isn’t visible from any public passageway—one of the legal requirements.

I’d been growing tomatoes, peppers, blueberries, and other flowers and vegetables in pots for years, so I mixed organic potting soil with horse-manure compost from the arabber stable and put it in 10-gallon clay pots and planted the two six-inch clippings.

Later, I got some more clipping “clones”—a Cindy 99 and Peanut Butter Breath. The Farmer gave me the plants for free and just asked to taste my produce when it was done. On the black market, I paid Kurt $20 each for clippings. For those, instead of buying big new clay pots, which had been expensive, I used pots I already had. I spent about $150 on my operation.

Now, if you don’t know anyone in the legacy market, you can buy seeds at various dispensaries like Liberty, which used to be Maggie’s in Hampden, and clippings at The Living Room in Pikesville, among other places, for about $40.

“I’M TALKING ABOUT THE ‘LOVEY-DOVEY’ KIND OF LIKE. THIS IS PLANT MEDICINE. YOU KNOW, THIS IS SACRED.”

At first, I shied away from specialized fertilizer, letting the plants be their plant selves, as I did with my tomatoes. But the going was slow, and they remained runty. Talking to various growers and reading online forums, I realized in late July that my plants were less well-developed than they should be, so I began using fertilizers intended for cannabis.

In between, I spent a lot of time trimming fan leaves—the famous five-pronged ones—which suck energy and light from the more crucial flowers. I bought red clips that I could loop branches through, guiding them outward and allowing more air to reach the buds, which prevents mold or other fungal infections. Once, I thought I had developed a milky white infestation, but it was, as the Farmer informed me, my first evidence of the “glorious trichomes,” which are the crystalline source of THC.

As my flowers formed, I bought a jeweler’s loupe for $20 to study the crystals on the small leaves surrounding the buds. I needed to harvest when they turned from a clear color to milky white and just before they turned brown. It was fascinating to watch and learn the language of the plant.

Ultimately, none of my plants grew much past my shoulders and none got bushier than a hefty tomato plant. Friends, including a local bar owner, had plants in the ground that towered far above their heads, but I was happy with my bushes.

I harvested my original Cindy 99 first. I cut it off at the root and took the entire plant into my downstairs half-bath, where I’d set up fans and a hygrometer to manage the humidity and temperature (six hygrometers cost me $12.68). I placed a shower rod from wall to wall and I tied the whole plant, upside down, to the rod. Hanging it upside down as it dries helps the sap and resins flow into the flowers, which are what you mainly want to keep—though the small leaves with trichrome crystals are also great for making tinctures.

I let the plant hang for a week, checking its moisture levels daily. I also cut the White Widow and hung it. When the stems of the Cindy broke easily—a sign they’d dried out—I untied it and trimmed the plant. I bought a pair of sharp, spring-loaded scissors and a plastic sheet to cover the table, and first cut all the major branches.

From there, it got more granular, until I was trimming the small leaves away from each of the buds. This takes hours and can get real sticky he indoor ones I normally buy, but there was a lovely freshness to them. I sampled the flower, but it was like moonshine or Beaujolais wine: It needed to be aged and cured to stabilize the terpenes and pull the moisture out of its center.

After I’d trimmed them, I put the flowers in jars with hygrometers and put them in a dark cabinet. I checked the humidity and “burped” the jars (opening them to let gas out) a few times a day, then tapering to once every couple of days until they had been cured.

Ultimately, my plants produced about five ounces of weed. If you don’t know measurements, that’s a fair amount—certainly a felony back in the day. For scale, a nice, big joint might weigh a gram. There are 28 grams in an ounce, so enough to roll about 140 fatties.

From the beginning, I intended to share as much of the weed as I could. I’d wanted to grow it in the sun, for love, in the hopes of making it special in the same way a tomato grown at home is special.

Given the timing, Thanksgiving weekend seemed like the perfect occasion to share and celebrate the harvest. I walked around that week with my pockets stuffed with pot and gave away a little more than an ounce in small gift-sizes. It always made people smile when I handed them their present.

Those who reported back were impressed, too. One guy wanted to buy a pound to get a recording artist he had in the studio out of a rut. I laughed to myself. I liked imagining my weed could get his rapper out of a rut.

It had gotten me through an otherwise difficult summer that included the death of my mother. I had learned a lot. I knew I would do better, but likely make different mistakes next year.

Though I’d been smoking for 35 years, I feel like growing the plant taught me far more than anything else I’d read or been told.

I was learning to care for a plant that had long cared for me.