News & Community

Public Trust

Fifty years in, Maryland Public Television continues to look to the future.

Up a tree-covered drive in Owings Mills, the small hill that is home to Maryland Public Television has grown quiet for the evening. The parking lot of the old brick building sits half empty, and though the lobby glows warmly, there’s no one sitting behind the front desk or on the waiting area’s tan mid-century sofas. The offices are also dark, and aside from the wooden frames hung with faded portraits of colleagues and guests past, the hallways are deserted.

But around the corner, inside Studio B, just before 8 o’clock on this Monday night—under a canopy of metal lights, the floors swept, the stately set tidied, and big black cameras set around the room like giant chess pieces—the work has just begun.

A few dozen volunteers ready the phone banks and rehearse the evening’s lines before Rhea Feikin, the star of tonight’s pledge drive, decked in a salmon-colored pantsuit and silk neck scarf, steps through the side door. Across the way, a team of directors and producers hustle about the control room, sliding into their swivel chairs and tending to their respective computer screens just as the countdown begins: 5, 4, 3, 2…

“The television studio is just a black box with lighting and air conditioning,” says George Beneman, MPT’s head of technology. “The magic is what happens inside.”

In perfect synchronicity, the red “ON AIR” sign lights up in the hallway. Feikin smiles into the camera, then launched into her pitch. The phones begin to ring. The show has officially begun.

“The television studio is just a black box . . . The magic is what happens inside.”

Public television was born in the 1950s, when those little glowing sets first became fixtures in American living rooms after World War II. But it wasn’t until the late 1960s that the medium found its real footing, just as the country sunk into a state of deep division and unrest. The Vietnam War was underway abroad, and here at home, Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination incited riots nationwide.

Public television, with its focus on education and community, suddenly seemed like a great unifier. Its programs could “help us see America whole, in all its diversity,” wrote the Carnegie Commission in 1967, leading to the creation of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting that same year, which would give rise to the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) and National Public Radio (NPR).

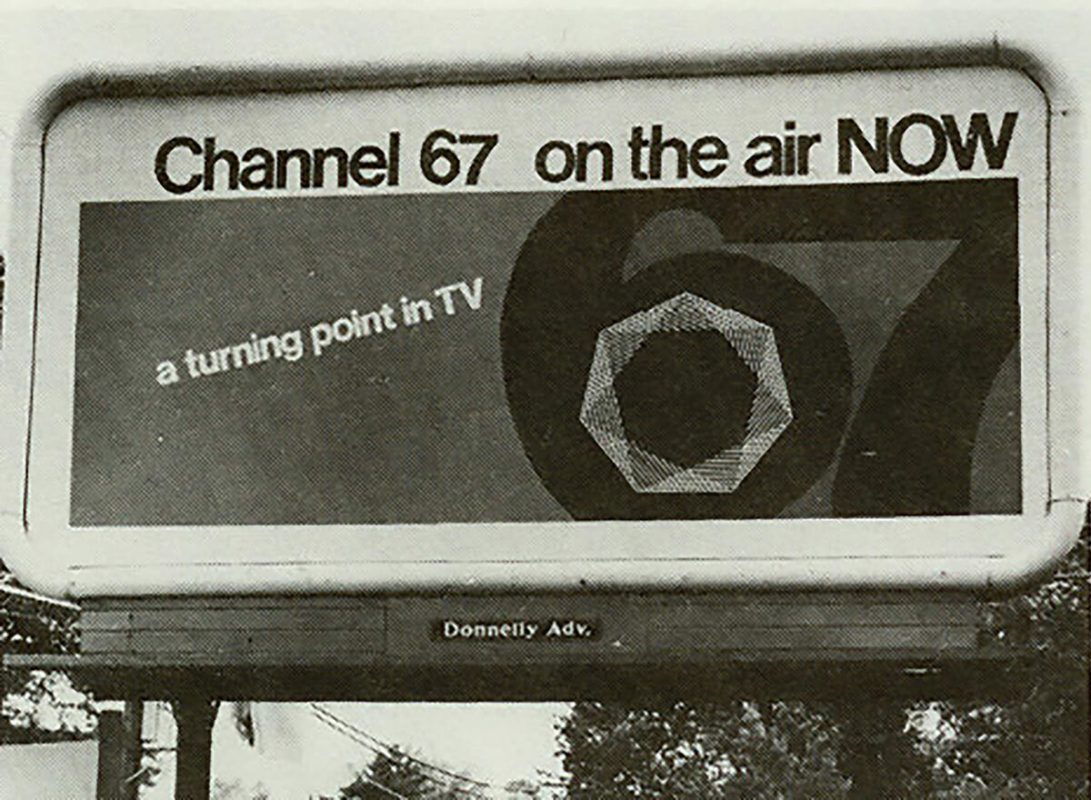

But before PBS made its debut in 1970, a group of Maryland citizens had already started to lobby for state-supported educational television, sanctioned by Governor J. Millard Tawes in 1966. Twenty acres of the Gwynnbrook State Game Farm in Baltimore County were sectioned off for a new state-of-the-art television facility, while a staff was formed in Baltimore City, converting a St. Paul Street apartment building into temporary office space. Before long, Channel 67 was acquired and a golden shovel, which is still framed in the front lobby, broke ground in the then-hinterlands of Owings Mills.

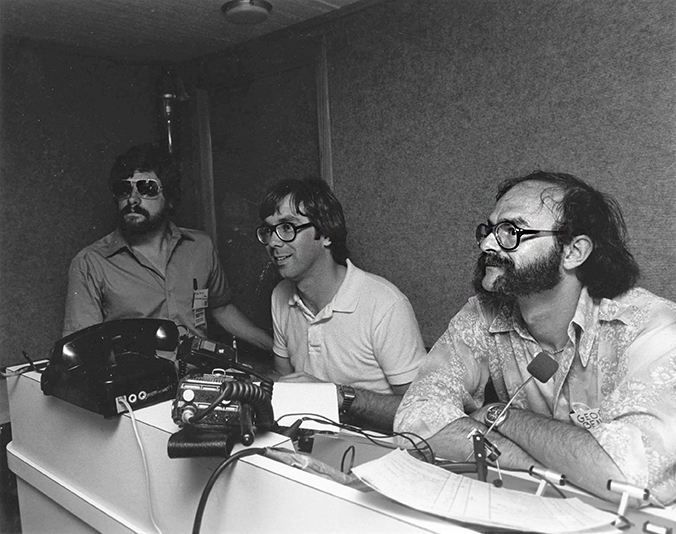

Just over a year later, the Maryland Center for Public Broadcasting—the predecessor of modern-day MPT—would open its doors in August 1969, and a ragtag crew of creative young people would get to work on creating brand-new, hyper-localized programming from the ground up. “It was a very exciting time—a young, vibrant, inventive place,” says Beneman, the company’s longest-tenured employee, who started as a studio camera operator that first year before moving up the ranks. “What was public television? What did we want it to be? We were going to change the world.”

George Beneman (right) with fellow staff during filming of an MPT production; Groundbreaking for the original Maryland Center of Public Broadcasting, CIRCA 1968; “Miss Jean” feeding Aurora in front of the Hodgepodge Lodge, circa 1970s -Courtesy of Maryland Public Television

Even as a state agency, the environment was more collegiate than corporate, with a diverse mix of people of different ages, races, and genders in every role, and each employee encouraged to spread their wings. The staff, like many arts organizations across the country, was double the size it is today, with writers, editors, producers, directors, cameramen, photographers, musicians, and composers all on payroll, plus a full scenic shop filled with carpenters, painters, and designers who crafted the sets by hand.

There was the talent, too, like Miss Jean, the center’s actual neighbor—who landed her beloved kids’ show, Hodgepodge Lodge, after walking through the woods during construction to inquire about all the noise—and eventually Feikin, the MPT pledge queen. A small Walk of Fame in the front plaza now celebrates their tenure with Hollywood stars.

“It was all so new,” recalls Feikin. “People came here from different walks of life, and they would stay for years and years.” Some two dozen couples would even meet there, like Beneman and his wife, Tina, who starred in her own organic gardening show.

The station was a sea change for Maryland, too, as the region only carried a handful of channels back then. “It was a big deal, because we only had three stations in Baltimore—2, 11, and 13,” says John Shields, chef-owner at Gertrude’s Chesapeake Kitchen, who hosted MPT programs Chesapeake Bay Cooking and Coastal Cooking. “We were getting another station … and one without commercials!” (In an already oversaturated world, public broadcasting avoids advertising as part of its non-profit mission.)

When Channel 67 went live for the first time on Sunday, October 5, 1969, the station and its staff made their ambitions known, launching the inaugural telecast with the center’s first original series, Stories of Maryland, and on Monday morning, they would start airing their own educational programming for local school students. About a month later, they broadcast the national debut of Sesame Street, with viewing centers set up for inner-city kids in downtown Baltimore.

From the earliest days, MPT was dedicated to capturing the sense of place of its diverse state, long known as “America in Miniature,” and over time, new transmitter towers would help spread the station’s reach across all of Maryland and into surrounding states. The station would detail both rural and city life, from the mountains of Western Maryland to the sands of Ocean City to the streets of Baltimore, launching groundbreaking urban series like Our Street, a soap opera about an African-American family from East Baltimore. For the first time, many state residents saw their communities on the small screen.

“It really is the station of the people. You don’t have to have cable or a credit card to see it.”

Over the years, MPT has produced more than 850 productions, leaving few topics unturned, from women in the workplace and global warming to veterans and the opioid epidemic, winning national and regional Emmy Awards along the way. They celebrated notable Marylanders, such as H.L. Mencken, Barbara Mikulski, and the Baltimore arabbers. They commemorated the opening of Harborplace and the Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. They covered the arts, and sports, and the great outdoors, extensively. And now, two highly anticipated documentaries on Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass are in the works.

The station has also been a source for local, regional, and national news. When The Baltimore Sun went on strike in 1970, the Owings Mills studios housed print journalists who delivered their beats on air, and during the Watergate scandal, they suspended programming to show the investigation hearings in their entirety. They’ve hosted town halls, political debates, and steadily addressed public affairs, as shown in the ongoing State Circle and Direct Connection. “It really is the station of the people,” says Shields. “You don’t have to have cable or a credit card to see it. It’s not driven by big bucks. It’s a station that is made for Maryland, and the entire region.’”

At the same time, public stations like MPT have also made their mark on a larger scale by launching niche shows decades before they would become dedicated channels on cable. Take 1970’s Wall $treet Week, about which declared: “Who would have thought the financial press would have some rivalry from Channel 67 atop a Maryland hill?” Or 1981’s MotorWeek, which became television’s longest-running car show (and is still the station’s best performing series). “Public television was really the original Cooking Channel—Madeleine Kamman, Jacques Pépin, Julia Child,” adds Shields, whose own programs have been household favorites since the late 1990s.

But perhaps the most well-known programs, especially in recent years, are the live pledge drives, tied to that now-famous slogan: “Made possible by viewers like you.” On-air fundraising has been a vital staple for public television since its inception, with monetary contributions from audience members—often in exchange for gifts such as coffee mugs and DVD sets—being a lifeline for the noncommercial stations.

“I’m a good begger, I guess,” says Feikin, who began spreading the MPT gospel in the 1970s and whose fans have come to love her native Bawlmer accent and no-bull attitude. Even once, “I was sitting by the pool in Thailand, and all of a sudden, I hear a man’s voice yell, ‘Miss Rhea! I pledged!’ I look over to see his arm lifting up one of our tote bags!”

Lately, though, MPT has been working to limit its pledge drives, which some viewers have come to consider a nuisance. Today, the station operates with an annual budget of $34 million, of which they receive some 25 percent from the state and nearly eight percent from the federally funded Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which the Trump Administration continues to threaten. Filling in the rest is up to them, which they do through on-air contributions, online donations, and memberships, with some loyal viewers even leaving money to MPT in their wills.

And it’s an uphill battle. One of their largest hurdles these days is attracting a younger audience, as the majority of the 1.3 million people who tune in to the station’s two main channels, MPT and the lifestyle-focused MPT2, are 65 and over. Add to that the rise of cable television and, more recently, “cord cutters” who are switching to streaming services like HBO and Hulu. Even Beneman would have to think long and hard before choosing broadcast television over Netflix, and that’s coming from a man who still reads two newspapers a day. “I like the ritual, the same way I like turning the dial,” he says. “But those days are gone.”

Of course, MPT has seen changes before, like the switch from analog to digital broadcasting in the late ’90s—the biggest technological advancement since color television. Not long after, they launched their website, and in the next decade, wrote their first Facebook post. In recent years, they also introduced MPT Digital Studios for web-exclusive content and a mobile app for on-demand video, which could help bridge their age gap. And now they’re thinking about 2020, when ATSC 3.0, the next-generation broadcast standard—think of it as smarter than smart TV—might make its official debut.

“A lot of people are frightened by change,” says CEO Larry Unger. “But if you’re quick enough and smart enough, you can end up better for it.”

Still, the future remains unknown. “If anyone thinks they know what we’ll see a few years out, God bless them,” says Beneman. “You can’t even put money on whether or not the Preakness will still be in Baltimore. But, we’re getting ready.”

At 50 years old, the station is looking forward more than it’s looking back. Sure, the anniversary brings about celebrations steeped in nostalgia, but they’ve also just broken ground on a $9-million renovation of Studio A, their pièce de résistance and largest black box with lighting and air conditioning. The project is Beneman’s baby—bringing the old brick building, still charmingly 1960s, into the 21st century—and his eyes light up when he talks about all the possibilities that lie ahead.

Meanwhile, the old control room where he has made so much magic happen over the past five decades has just been named in his honor. He still finds himself there often.

Even after all these years, “When a show starts, no matter what it is, there’s still that excitement, that adrenaline rush,” says Beneman. “That never goes away.”