Sports

Fish Tales

At the World’s richest BillFishing Tournament, catching the biggest marlin may earn you millions. But not until you pass the polygraph.

The fish that won Glen Frost $1.65 million had probably been hooked before. Caught 55 miles off the Maryland coast, on the edge of a deepwater shelf along the submarine Baltimore Canyon, the white marlin was huge—close to 8 feet from its rapier bill to its forked tail fin—tipping the scales when it was brought back to the docks at Ocean City’s Harbour Island Marina at nearly 100 pounds. Pulled in at the 11th hour of last year’s White Marlin Open, it was the third-largest white marlin landed in the tournament’s nearly four and a half decades, and its girth indicated it had been around for a while, maybe 25 or 30 years, and knew how to get off a line. “Certainly not a dumb fish if it had grown that big,” Frost says. “And it did everything it could to get away.”

The fish that won Glen Frost $1.65 million had probably been hooked before. Caught 55 miles off the Maryland coast, on the edge of a deepwater shelf along the submarine Baltimore Canyon, the white marlin was huge—close to 8 feet from its rapier bill to its forked tail fin—tipping the scales when it was brought back to the docks at Ocean City’s Harbour Island Marina at nearly 100 pounds. Pulled in at the 11th hour of last year’s White Marlin Open, it was the third-largest white marlin landed in the tournament’s nearly four and a half decades, and its girth indicated it had been around for a while, maybe 25 or 30 years, and knew how to get off a line. “Certainly not a dumb fish if it had grown that big,” Frost says. “And it did everything it could to get away.”

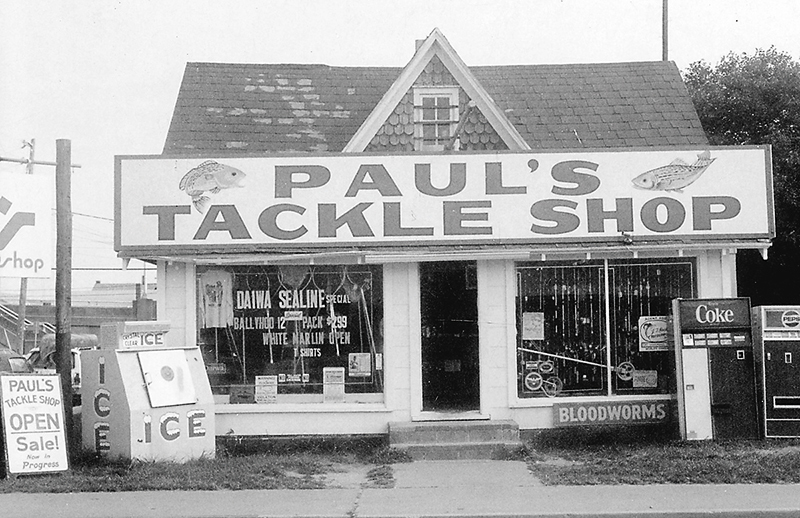

PAUL'S TACKLE SHOP, the longtime center of sport fishing in the area. - DALE TIMMONS

A successful Annapolis-based tax attorney who grew up fishing the Gunpowder River in Baltimore County, Frost is a serious outdoorsman. He lives at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on Kent Island and has fished the Pacific off Costa Rica and Panama. He estimates it took him 20-25 minutes to reel in the prize-winning catch, which he caught in the final afternoon hours before the official end of the five-day tournament. “It jumped [out of the water] several times. I saw right away it was a white marlin,” Frost says. “I knew I had to keep the line as tight as I could. Otherwise it would shake its head until the lure came loose. I just had tunnel vision. Nothing else in the world existed for those 20-25 minutes except me and that fish.”

Winning the “Super Bowl of Sport Fishing,” as the White Marlin Open is sometimes called, in such dramatic fashion was a thrill beyond Frost’s wildest dreams. Getting strapped to a polygraph machine the next morning inside a claustrophobic hotel room on Coastal Highway, not so much. “It was an interrogation,” says the 33-year-old Frost, adding he won’t be competing in the tournament again this month—or, most likely, ever. “They were very aggressive.”

Here’s the catch with the White Marlin Open—the largest and richest billfishing tournament in the world—and similar big-money fishing events: The stakes are so high, the cheating so widespread, that organizers must institute protections to maintain the integrity of the competition. Back in the early 2000s, the WMO implemented polygraph tests for winners for the first time, and now anyone winning more than $50,000 is basically required to submit to a lie-detector screening before they can collect their dough (the total purse for this month’s 45th annual tournament is expected to exceed $5 million).

Those polygraphs are to ensure anglers play by the rules, that they don’t rig illegal lures or stuff their catches with ice, smaller fish, or lead sinkers—all of which have been done at other tournaments—to add weight. Or that the winning fish hasn’t been pre-purchased from a commercial trawler—which, yes, has happened, too—and packed in ice before the tournament. Or that the winning boat didn’t drop lines in the water prior to the official start time, which is the rule the 2016 White Marlin Open winner was actually found guilty of violating. That federal case, The White Marlin Open, Inc. et al v. Philip G. Heasley, the most expensive scandal in sport fishing history, was finally decided a couple of months ago in U.S. District Court in Baltimore. It cost Heasley, the CEO of a Florida-based financial company, all of his $2.82 million in winnings—more money than Tiger Woods ever took home for winning the Masters golf tournament.

In fact, it cost him more than the $2.82 million in winnings. Heasley spent, “conservatively”—his word—$3 million in legal fees trying to win back his title.

If this all sounds a little crazy, it’s about to get crazier: While Frost was out hooking his award-winning marlin last August, he was also a lawyer involved in the litigation surrounding the contested 2016 results. Some members of the crew he was representing—anglers who stood to receive additional purse money freed if the courts ruled Heasley’s team had started fishing too early the year before—had invited him to cast lines with them.

The Case cost Heasley all of his $2.82 Million in winnings–more money than tiger woods ever took home for winning the masters golf tournament.

In other words, Frost caught the 2017 winning white marlin in the Atlantic as he was helping take down the 2016 tourney winner in a Lombard Street courtroom. But hold on. This is a fishing story, so there’s always one more twist. Frost did not pass his initial polygraph last year.

The White Marlin Open issued a press release immediately after the contest last August stating one winner had failed their polygraph—nine fishermen who stood to take home more than $50,000 in purse money were tested—and another winning angler’s initial exam had come back “inconclusive.” In June, WMO founder Jim Motsko confirmed to Baltimore that last year’s inconclusive result, which wasn’t made public, had indeed come from Frost, who did later pass a second polygraph and receive his giant check after a two-month-long investigation. (Motsko noted Frost had been the only member of his boat who hadn’t passed his initial polygraph; in Heasley’s case, all four of the crew members failed.)

When asked about the details of his lie-detector test, Frost declined to answer. Nor did he wish to respond to queries about the follow-up exam or the nature of the questions he was asked while attached to the machine. He would only describe the whole thing afterward as “very bizarre.” “It should be named the White Marlin Fishing Open and Polygraph Tournament.”

WHITE MARLIN OPEN FOUNDER JIM MOTSKO. -AP Photo/Patrick Semansky

According to a long-ago history penned by James Edward “Scoop” Collins, an Ocean City businessman and World War II Navy veteran, it was a Florida angler, Capt. John Mickle, who caught the first recorded marlin off the Maryland coast, hooking a single white in 1934. A year earlier, the Great Hurricane of 1933 had dumped a week of rain before driving 80-mph winds and a 7-foot tide to shore, unexpectedly carving out a natural inlet over the worst of its 36-hour span. The monumental disaster turned Assateague into an island and, fortuitously, it turned out, opened a gaping passage to the Atlantic from Ocean City, a boon to the town’s fishing and resort economy.

According to a long-ago history penned by James Edward “Scoop” Collins, an Ocean City businessman and World War II Navy veteran, it was a Florida angler, Capt. John Mickle, who caught the first recorded marlin off the Maryland coast, hooking a single white in 1934. A year earlier, the Great Hurricane of 1933 had dumped a week of rain before driving 80-mph winds and a 7-foot tide to shore, unexpectedly carving out a natural inlet over the worst of its 36-hour span. The monumental disaster turned Assateague into an island and, fortuitously, it turned out, opened a gaping passage to the Atlantic from Ocean City, a boon to the town’s fishing and resort economy.

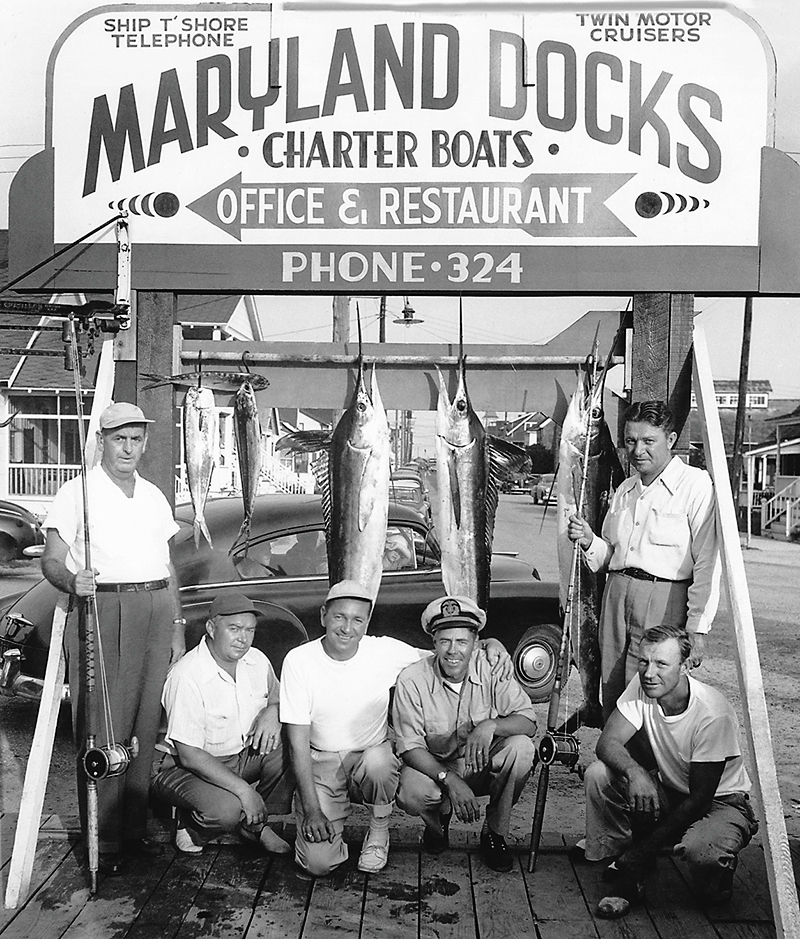

FISHERMEN on THE Docks with three white marlin caught near Ocean City circa 1950. -GETTY IMAGES

It was also in 1934, in the storm’s aftermath, that angler Jack Townsend, fishing with his brother, Paul, first discovered a mother lode of white marlin offshore—at a destination still known as “The Jackspot”—that would later earn O.C. the title “White Marlin Capital of the World.” On July 29, 1939, a record 171 white marlin were boated at Townsend’s favorite spot—at the time, the greatest single-day haul of white marlin ever recorded anywhere. Attracted by the burgeoning publicity surrounding the billfishing hotbed, celebrities from all over the East Coast had started making forays to the Delmarva Peninsula. President Franklin D. Roosevelt arrived too late from Washington that record-breaking Saturday to land any white marlin, but he caught two the next day.

Those halcyon days peaked in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when an average of more than 2,200 of the fast-swimming fish were caught each year. (No period since has remotely approached those figures, largely, it’s suspected, because of inadvertent killings by commercial trawlers.) It was on the cusp of that era, in 1966, that Motsko, then a 20-year-old College Park student with a love for fishing, came down to Ocean City and got hired as a mate on Capt. Fred Kerstetter’s boat, Katherine.

After finishing school and trying his hand at banking and real estate, Motsko continued to pull summers as a mate on various boats. Still wiry and perpetually in motion at 71, he explains that he desperately wanted to find a way to stay in the fishing business year-round. “I had one job [working on a boat] that I loved but didn’t make any money; another I didn’t like [in a bank] and didn’t make any money; and another [in real estate] that I hated but made money,” Motsko recalls. “I remember telling my wife, ‘Wouldn’t it be great to do something that you liked and also make a little money?’ But I really started the tournament so I could fish it. I couldn’t afford to pay a charter and enter one of the events that were around then.” (For the record, Motsko fished his tournament for the first 34 years, winning money—$4,000—once.)

THE HEAVIEST WHITE MARLIN EVER CAUGHT AT THE WMO. -dale timmons

In 1974, the first tournament drew 57 boats vying for $20,000 in prize money, and Ocean City Mayor Harry Kelly presented a $5,000 check (which thankfully didn’t bounce) to the winner. The week was plagued by wind and rain, and when it was over, Motsko had lost money. “The first two years, we had to get a loan to pay the winners. The third year, we broke even, and I thought we were on our way because we didn’t have to borrow money to pay out the prizes,” Motsko says with a laugh. Right about that time, Motsko also purchased Paul’s Tackle Shop, which had been open for 30 years and was the center of big-game fishing in the area. With the tackle shop serving as base of operations, the tournament drew 147 boats in 1977, surpassing all other billfishing tournaments in the world—an honor it has held ever since—and becoming a family enterprise in the process when his two daughters joined the business. Last year, nearly 3,000 anglers in 353 registered boats entered the fray, many paying up to $30,000 to participate in the tournament’s big betting pools, which are known as calcuttas and generate the huge payouts. “We took it year by year,” Motsko says. “Never in my life did I dream this.”

By “this,” Motsko means the biggest week of the year in Ocean City, when hotels and slips are booked solid; when the restaurants, beaches, and boardwalk are packed; and the invasion of hi-tech, 60-foot-plus boats, and gigantic dead fish draw thousands of fans to the daily weigh-ins.

And, now, of course, the controversy and litigation.

“It’s been a miserable two years,” Motsko admits. “But we were backed into a corner.”

the official weigh-ins at Harbour Island, WHERE PARTYING CROWDS watch the anglers bring in their DAILY CATCHES. -getty images

If you are not a sport fisherman, if your only contact with sea life comes via a menu or the National Aquarium, it may be difficult to get a feel for the White Marlin Open. It’s kind of like NASCAR on the ocean. “A battle of redneck pride,” Frost says with a laugh. The biggest, best, and fastest boats here generally cost in the $2 million to $5 million range—so it’s mostly a lot of rich guys who own these vessels, which, with their air conditioners, flat-screen TVs, granite-top kitchens, and stately bedrooms, feel more like luxury yachts than your pal’s little powerboat. (From a distance, when these boats take off together in the morning, they look like an armada of massive white Chevy Suburbans hauling ass across the water.) Some contestants simply hire charter boats for the tournament. Private owners, on the other hand, typically hire a captain and a pair of mates, similar to a pit crew, if you will, that enable the boat’s owner and friends to focus on fishing. And drinking beer. As with NASCAR, the politics of the participants and their fans also hue pretty conservative, which has occasionally sparked controversy. In 2016, “White Lives Matter” T-shirts produced by a local vendor mocked the Black Lives Matter movement with a nod to the namesake fish of the tournament.

If you are not a sport fisherman, if your only contact with sea life comes via a menu or the National Aquarium, it may be difficult to get a feel for the White Marlin Open. It’s kind of like NASCAR on the ocean. “A battle of redneck pride,” Frost says with a laugh. The biggest, best, and fastest boats here generally cost in the $2 million to $5 million range—so it’s mostly a lot of rich guys who own these vessels, which, with their air conditioners, flat-screen TVs, granite-top kitchens, and stately bedrooms, feel more like luxury yachts than your pal’s little powerboat. (From a distance, when these boats take off together in the morning, they look like an armada of massive white Chevy Suburbans hauling ass across the water.) Some contestants simply hire charter boats for the tournament. Private owners, on the other hand, typically hire a captain and a pair of mates, similar to a pit crew, if you will, that enable the boat’s owner and friends to focus on fishing. And drinking beer. As with NASCAR, the politics of the participants and their fans also hue pretty conservative, which has occasionally sparked controversy. In 2016, “White Lives Matter” T-shirts produced by a local vendor mocked the Black Lives Matter movement with a nod to the namesake fish of the tournament.

The names of some boats, too—Skirt Chaser, for example—also evoke a culture closer to say, Mad Men, than the 21st century.

anglers with a white marlin in Ocean City circa 1950. -getty images

But not every competitor is a financial-industry CEO or high-priced lawyer; more seem to have earned their fortunes in traditional, old-school family businesses—printing, construction, government contracting, manufacturing. They all, however, have modern advantages onboard: global-positioning technology, up-to-the-minute satellite weather information, current and mapping systems, and dual-dredge bait operations to attract their prey.

Sport fishing is still sport fishing, and even with all those fancy amenities, or maybe because of them, there is lot of sleeping-off hangovers on the way out to sea (runs to the nearby canyons take 4-5 hours, translating into 4 a.m. launches), and then waiting in the sun, sipping Coors Light and noshing sandwiches while hoping something takes an interest in one of the colorful plastic lures trailing off the back of the boat. “You’ve seen Jaws, right?” angler Frank Massa joked mischievously with a pair of fishing buddies as he cranked a big reel in super-slow motion last year aboard a boat up from Mobile, Alabama, imitating the foreboding click-click-click from the grizzled fisherman Quint’s first encounter with the movie’s infamous shark. In the 1975 film, that click-click-click served as the ever-so-subtle signal that the killer fish had grabbed the bait and was readying for an epic run.

Around the Alabama boat, however, all was calm for nearly their entire second day out. “That’s fishing: hours of boredom, interrupted by moments of chaos,” one of Massa’s crewmates chimed in after an early-morning catch, the only bite of the day.

Along with the top prize at the end of the week for the heaviest white marlin—the biggest payout—and for biggest blue marlin, tuna, wahoo, mahi-mahi, and shark, there are smaller daily prizes. Despite their names, the blues and the whites share the same color schemes: royal blue on top and a whitish-silver underneath. What sets them apart is their size. Blue marlin can grow to more than 1,000 pounds, 10 times the size of their white cousins. Blues are so enormous they generally aren’t afraid of anything, including biting on a line—the problem is getting them onto the boat. Whites are more cautious, and pound-for-pound extremely tough fighters, which is what makes them such a great challenge.

Certainly there is something primal to big-game fishing in what feels like the middle of the ocean. It’s tempting to say masculine as well, but more women, though still a tiny overall percentage, are fishing the tournament each year. (Cheryl McLeskey, of Virginia Beach, won in 2015 with a 94-pound white marlin.) There is also something disconcerting, to an outsider at least, in watching winners grin and pose for photos alongside the enormous, gorgeous fish they’ve just taken from the sea for sport and trophy.

A 1,062-pound blue marlin caught in 2009 at the white marlin open. -Larry Jock, Coastal Fisherman

The packed ritual weigh-ins at the Harbour Island Marina each afternoon and evening are also a little disconcerting. They are a strange blend of reality TV and spring break for sunburned, middle-aged adults. Bon Jovi, Tom Petty, and George Thorogood blare from the speakers. Local journalists (this is the stuff of front-page news in Delmarva) inevitably descend with notebooks and cameras for interviews as the hunters unload their catches and bask in the anticipation and attention of the crowd. Witnessing the slightly inebriated audience cheer and applaud while one of the huge animals is strung up by its tail overhead—its weight and length called out by an announcer—adds to the surreal spectacle.

The fact that these animals have been considered for the U.S. threatened species list—though commercial fishing lines, which inadvertently catch the marlins, are the overwhelming culprit—doesn’t dispel the feeling that sport fishing is more akin to a safari than fishing the local trout stream for recreation (and maybe dinner, if you’re lucky). The thousands of gallons of diesel fuel burned each tournament cannot be good for the marlin’s survival, either. The use of circle hooks, which are more difficult for fish to swallow, does make successful catch-and-release efforts for commercial and sport fishermen more likely and should help rebuild the stock of marlin and other fish. Motsko says that 98 percent of the billfish caught during the tournament are released.

“We’ve been at the forefront of conservation efforts,” Motsko says, adding that he’s also proud that hundreds of pounds of meat each year from the competition get filleted on the docks by a volunteer for the Maryland Food Bank.

An aerial view of the boats coming in at the White Marlin Open in Ocean City. -MARYLAND COAST DISPATCH

The most pressing concern facing the White Marlin Open is the continued use of so-called lie-detector tests. It’s a 1920s technology that, as most people know from TV detective shows and movies, measures physiological indices, including blood pressure, pulse, and respiration, as an individual, i.e., a likely suspect, is asked a series of questions. The underpinning theory is that false or deceptive responses generate physiological responses different from those associated with non-deceptive responses. Yet, no specific physiological reactions are associated with lying. Confounding matters, each polygraph examiner uses their own scoring method.

The most pressing concern facing the White Marlin Open is the continued use of so-called lie-detector tests. It’s a 1920s technology that, as most people know from TV detective shows and movies, measures physiological indices, including blood pressure, pulse, and respiration, as an individual, i.e., a likely suspect, is asked a series of questions. The underpinning theory is that false or deceptive responses generate physiological responses different from those associated with non-deceptive responses. Yet, no specific physiological reactions are associated with lying. Confounding matters, each polygraph examiner uses their own scoring method.

The FBI, the CIA, and many police departments may still use polygraphs in interrogations, but polygraphs are not admissible in prosecuting criminal cases because of their fallibility. They can, however—although it’s rare—sometimes be introduced as evidence when both parties have previously agreed to their use in the form of a contract, for example, as participants do in signing up for The White Marlin Open. A 2003 National Research Council study found “little basis” that a polygraph test would demonstrate an extremely high accuracy.

Ultimately, U.S. District Judge Richard D. Bennett ruled the polygraph exams could be admitted in the Heasley case and that the WMO complied with its obligations under tournament rules. He also went by more than polygraph tests in rendering his judgment: During eight days of testimony, Bennett looked at GPS reporting, photography and logs, as well as the crews’ conflicting accounts in concluding that fishing lines had been dropped prior to the official start time.

Heasley, for his part, told the court that “he never wears a watch” and that he had trusted his hired crew to follow the rules. He doesn’t believe, based on the evidence, that his team did anything wrong. He also says he defended himself in court against the tournament to protect his personal reputation and prove he had won the largest billfishing tournament in the world—an accomplishment, he acknowledges, he could hang a hat on for the rest of his life.

it's kind of like nascar on the ocean. "A battle of redneck pride," frost says. the biggest, best, and fastest boats here generally cost in the $2 million to $5 million range.

“Do I have regrets about spending that much money to fight this thing?” Heasley asks. “Absolutely, I do. I’d promised my crew half of anything we win, and I could’ve just given them each the share that I feel like we rightly won instead of spending it on lawyers. I also could’ve given the money to charity.”

Heasley, 69, one of nine children, grew up fishing on Long Island Sound with his grandfathers and dad. He referred to the polygraph testing as a dehumanizing experience. “They asked me if I had ever lied to my parents,” he says. “And if I had ever lied to my wife or would I. Of course I had lied to my parents, but I don’t want to answer those kind of questions in front of people I don’t know.”

Heasley has no intention of stopping fishing, but he is ambivalent about entering another high-stakes derby. Although, he did attempt to enter the White Marlin Open again last year. “They sent my [entrance] money back.”

He also is ambivalent regarding future legal action. His last appeal in federal court was denied, but a civil suit remains a possibility. “I’m in the ‘no’ camp,” Heasley says of further litigation. “But I have a lot of people around me in the ‘yes’ camp.”

Motsko maintains he has never accused Heasley or his crew of anything other than failing the polygraph tests. Once that happened, however, he was left with little choice but to strip their winnings—otherwise he faced lawsuits from other winners, who would inevitably demand their full cut of prize money.

“We started using it [the polygraph exams] because of rumors that kept flying around each year about cheating,” says Motsko. The 2016 and 2017 tournaments were not the first time for failed tests at the White Marlin Open. After the 2007 tournament, a second-place winner in the blue marlin category failed a pair of polygraphs, losing out on several hundred thousand dollars. “A lot of tournaments were already using them by the time we started [in 2004].”

The tournament has tried different refereeing approaches, including putting observers on boats, which is a practice used elsewhere. Motsko found it unworkable logistically. “With the early start times, boats deciding at the last minute which days to fish because of the weather, observers getting seasick, and other issues, it was impossible,” he says.

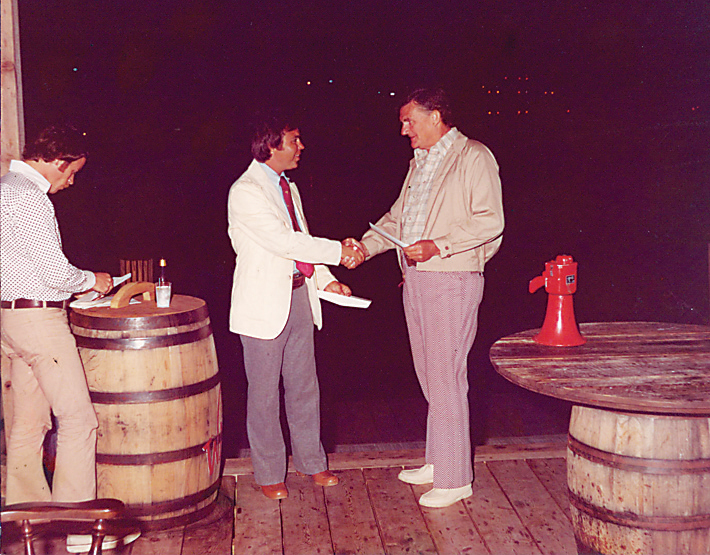

MOTSKO GIVING winner Vince Soranson His check IN 1974. -“B” Larry Bright

It should be noted that cheating in sport fishing is hardly limited to Maryland. In particular, it appears to be endemic to bass fishing, which has been plagued by black market networks that sell and deliver prize-winning fish to anglers. In Alabama, two men were sentenced to jail time for cheating in a tournament after being charged with tampering with a sport contest. Other states have enacted laws to combat the problem.

Some White Marlin Open participants have suggested placing video equipment on boats to expose cheating or deploying surveillance helicopters. The tournament’s boundaries are considerable, however, from Central New Jersey to Virginia Beach.

Motsko says he has no plans to make any changes.

Although Frost won’t be competing at this year’s tournament, he has no intention of missing it.

“I’m not fishing, but I am going down there this year,” Frost says, adding that the publicity from the trial has been great for his law business. “It’s still a great party all week. And who knows? I may even pick up another client.”

Because, as a trophy-hunting angler and tax attorney would understand better than anyone, greed and the desire to win are primal urges, too, as big as any marlin.