News & Community

How Frederick Law Olmsted’s Principles Shaped Baltimore Parks

Celebrating the father of American landscape architecture on the 200th anniversary of his birth.

Cheryl Duffey sits on a park bench in Locust Point surrounded by large planters sprouting annual flowers. Her two cocker spaniels lie at her feet on a beautiful herringbone brick terrace marking the entrance to Latrobe Park. She grabs the dogs’ leashes and enters the park, down a sweeping staircase and into an allée of trees.

“This is a well-utilized neighborhood park,” says Duffey, who is liaison for the Parks and Beautification committee of the Locust Point Civic Association. “When school lets out or on a weekend, the park is full.”

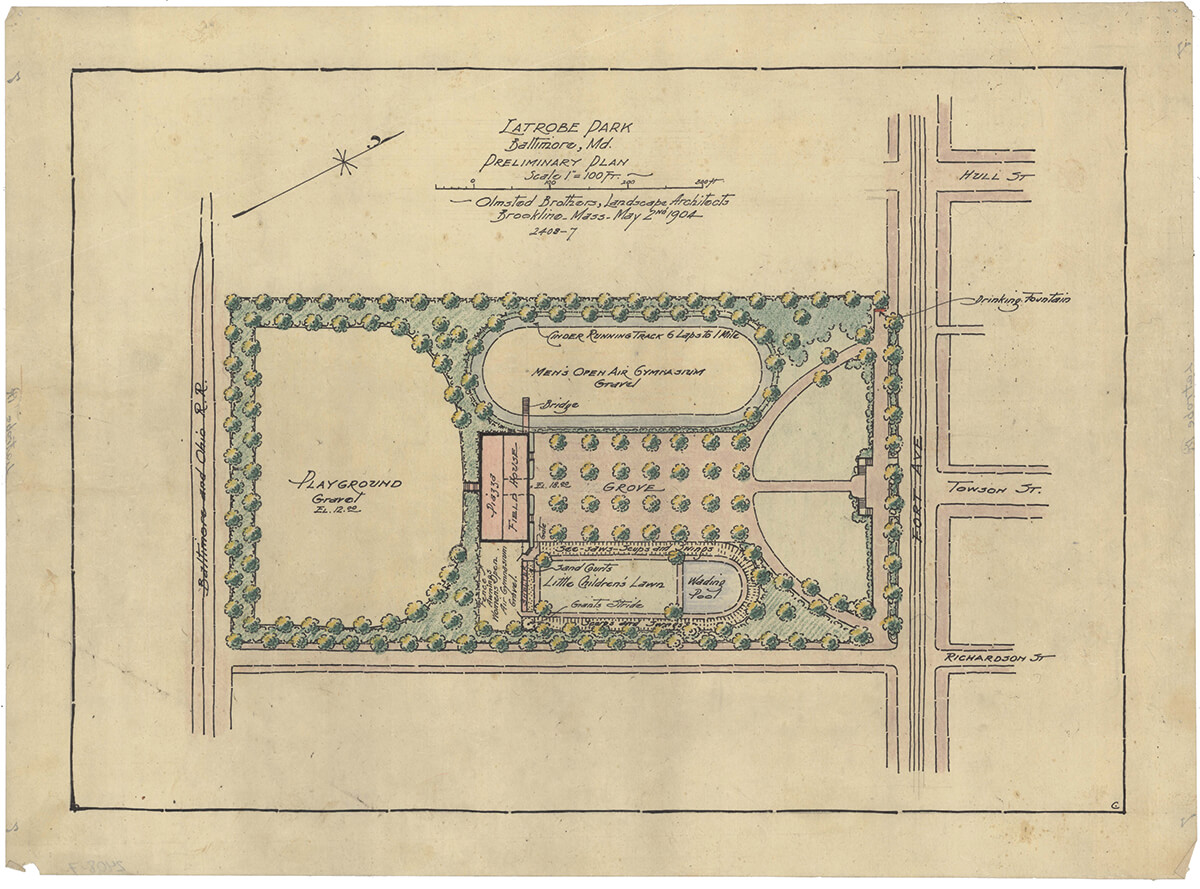

From the mature trees to local denizens using the space for everything from a volleyball game to a playdate, today’s Latrobe Park would still be recognizable to the Olmsted firm that designed and opened it in 1907. Yet many of the people whiling away a pleasant afternoon here likely have no idea they’re on land designed by the most revered landscape firm in America.

In May, Latrobe reinvigorated that history by placing a bronze plaque at the entrance honoring it as an Olmsted park. Latrobe also kicked off the first phase of the restoration of a pavilion, called “The Longhouse,” with a mural designed by local artist Nicole Buchholz that was painted by neighborhood residents.

“Community participation is an Olmstedian principle, and having residents paint the mural gives them ownership over ‘their’ park,” says Duffey. She says it is also imperative to reignite the cachet of the Olmsted legacy. “The Olmsted name is an invitation for people to come visit—and maybe for there to be more resources for upkeep, too.”

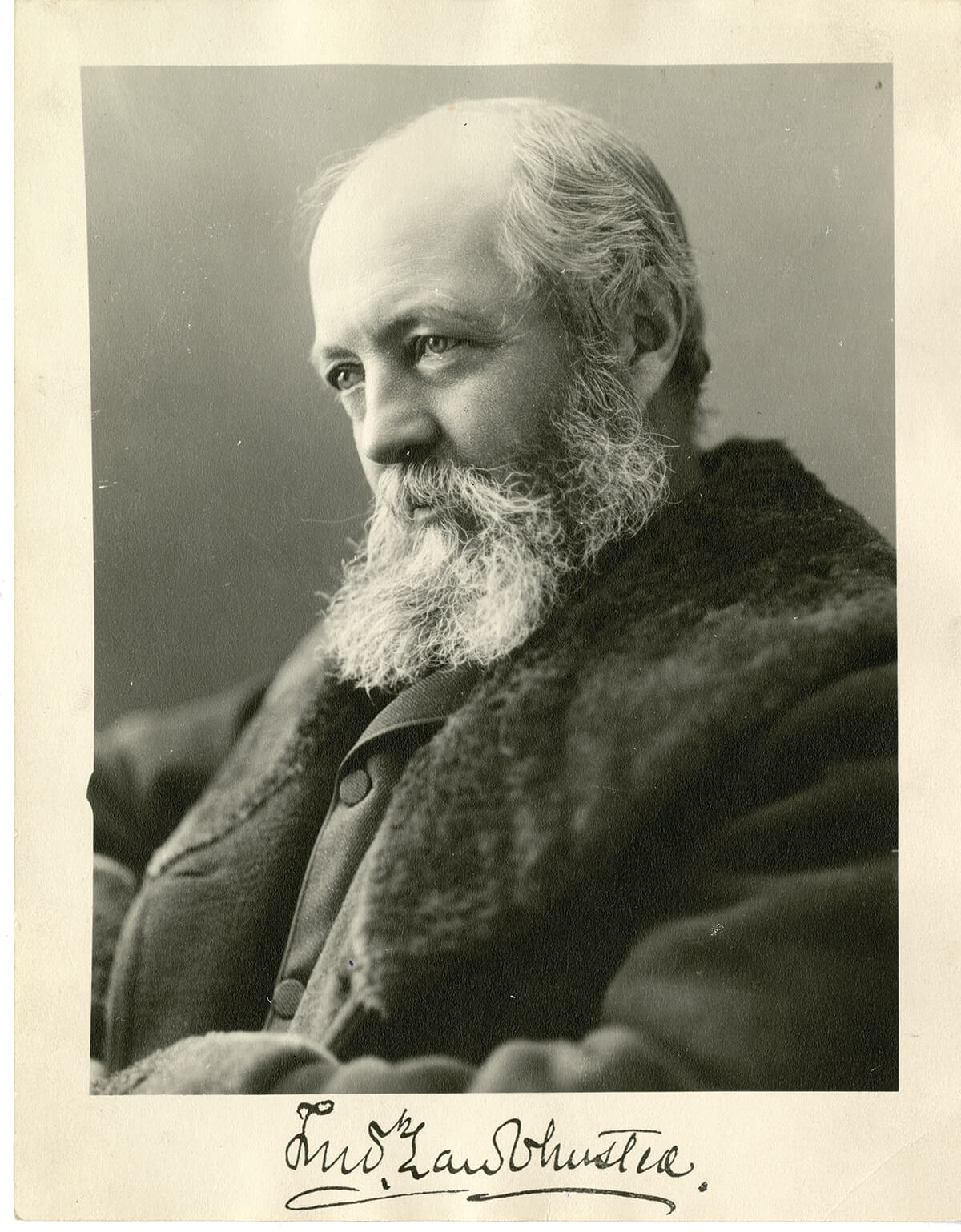

Frederick Law Olmsted is considered to be the father of American landscape architecture, having shaped much of this country’s greenspace from Central Park to the National Parks. Special events and celebrations of his projects—including Sudbrook Park in Pikesville and Mt. Vernon Place in Baltimore—are taking place nationwide in 2022 to mark the 200th anniversary of his birth.

For Latrobe and other parks, it’s a chance to remember Olmsted, whom biographer Justin Martin describes as “the most important American historical figure that the average person knows the least about,” but also to bring attention to his beliefs that parks are essential to democracy and a healthy populace—not just utilitarian places to take the dog for a morning pee.

Olmsted’s designs are beloved for their naturalism, their abundant use of trees, their gentle ambling paths, quiet groves, and open vistas. He wanted parks to be places of serenity and community, particularly as the country healed from the horrors of the Civil War. (So while it’s true that he would recognize Latrobe Park, morning joggers would likely have mystified him.)

His designs make up the fabric of the American landscape as we know it. Along with Central Park, his projects include Boston’s Emerald Necklace and the Capitol grounds in Washington, D.C. He helped preserve Yosemite and Niagara Falls and designed the Biltmore in North Carolina. Olmsted (and the namesake firms that were formed after his death, first operated by his sons as Olmsted Brothers, later as Olmsted Associates) is responsible for more than 1,000 parks and parkway systems and more than 6,000 private and public commissions in the U.S. and Canada over a roughly 100-year period.

Yet Dede Neal Petri, president and CEO of the National Association for Olmsted Parks (NAOP), which is spearheading the yearlong “Olmsted 200” celebration, explains that while Olmsted’s projects are numerous and illustrious, “what we’re focused on with the bicentennial year are the principles behind the parks.” “Parks are viewed as luxuries, but Olmsted saw them as an essential part of our urban infrastructure,” she says. He was also advocating for better and more accessible parks at a time when they were, if they existed at all, private.

“We hope to advance education about the Olmsted firm and its legacy, but, more importantly, we hope to engender a new appreciation and support for the parks, because they’re not self-sustaining,” Petri continues. “Today we need places where people can come together for mental and physical health; we need thriving parks at a time of climate change, and it will call on the commitment of all of us to ensure these parks are around for another generation.”

OLMSTED’S DESIGNS ARE BELOVED FOR THEIR NATURALISM, ABUNDANT USE OF TREES, GENTLE AMBLING PATHS, QUIET GROVES, AND OPEN VISTAS.

When Duffey moved to Locust Point in 2002, the neighbors were aging and so was the park. What is today the herringbone brick terrace was then a stretch of cracked concrete, and the “playground” was just a few swings and a set of monkey bars. Community activists like Duffey, supported by the city and other partners, have revitalized the park with a sprawling playground and fieldhouse as well as the renovated Long House with its brightly colored mural. The park has evolved to reflect both the neighborhood’s vibrancy and to meet its present-day needs.

This is what Olmsted believed—that parks should be for their communities. When he created Central Park, he stated, “The Park is intended to furnish healthful recreation…for the poor and the rich, the young and old, the vicious and the virtuous.”

It feels particularly appropriate to celebrate Olmsted in 2022. There is, after all, an opportunity here to learn from history.

“Olmsted was born in 1822 and grew up in pre-Civil War America,” says Petri. “It was a very divided country. There was massive immigration. Not unlike today, it was a time of many pandemics, with all types of diseases impacting the American population. And it was a time when we were moving from a rural to an urban society.

“Olmsted’s principles of parks bringing people together, of parks as essential to a democratic society, are very important even as we as a country are going through a racial reckoning and as we go through a pandemic,” she notes. “It’s almost eerie to see the similarities of what Olmsted was dealing with in the 19th century and the challenges we face today.”

While now known for his landscapes, for much of Olmsted’s life he stumbled into various careers. Raised to be a gentleman farmer, Olmsted charmed his way into a gig on a merchant ship and sailed to China despite having no experience at sea. Through friends he was given the opportunity to travel the pre-Civil War South documenting slavery for what is today The New York Times. His collected columns, The Cotton Kingdom, can still be bought on Amazon and was a formative read for Malcom X. The experience made Olmsted an abolitionist and informed his idea that parks must be for all people. He worked on sanitation commissions and provided medical services to the Union Army during the Civil War. He was originally hired in New York not as a landscape architect, but a superintendent in charge of clearing away stones and draining swamps to make way for the soon-to-be developed Central Park. It was only when a competition opened to create a blueprint for the park’s design that Olmsted found his life’s calling.

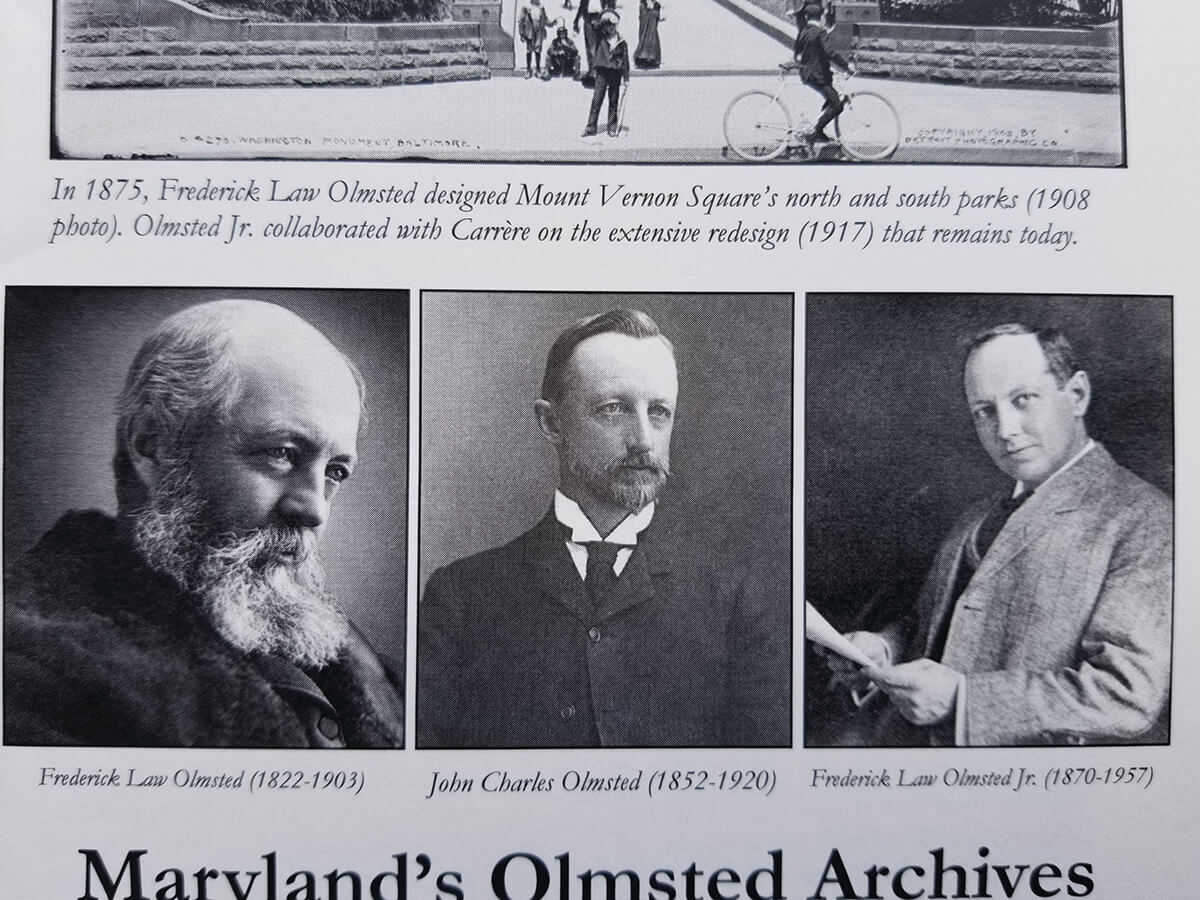

In Baltimore, it was, in fact, Olmsted’s sons, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and John Charles, both inculcated in Olmsted’s ideas from youth, who had the greatest impact on the city.

For much of his adult life, Olmsted was plagued by an injury from a near-fatal carriage accident, in addition to struggling with ongoing mental health issues. He died in an asylum at age 81 where he—fittingly or perhaps ironically—had drawn designs for the grounds. Olmsted Jr. and John Charles went on to have nearly as illustrious careers as their father, and they proved to be just as impactful to landscape design. Olmsted Jr. helped write the bill that created the National Park Service, for example, and created the first-ever university course in landscape architecture at Harvard.

The Olmsteds designed 136 projects in Maryland, including Homeland, Guilford, and Roland Park. But their Report Upon the Development of Public Grounds for Greater Baltimore, known simply as the 1904 report, shaped the Baltimore greenspace of today.

Retired UMBC American Studies professor and Olmsted historian Ed Orser describes Baltimore at the turn of the last century as the sixth largest city in the country, teeming with people living in crowded rowhouses surrounded by belching industry. The population was growing, the city was expanding, and residents would need places to get fresh air.

“[Baltimore] civic leaders at the time knew the Olmsted Brothers had designed in Paris, London, and New York and they wanted to be in that same company. Every city wanted an Olmsted park,” Orser explains.

Olmsted Jr. is cited as a pioneer of city planning, and the 1904 report is emblematic of that. “What makes the 1904 masterplan visionary is that it was not just for how the city was, but for how it would be,” says Orser.

The brothers envisioned a system of parks and parkways like Boston’s Emerald Necklace, but Baltimore City was too developed to create some of the much-needed connections. Still, they helped the city plan for the acquisition of already “park-like” lands, like the Clifton and Carroll estates, that were rapidly being engulfed by the city. Olmsted Jr. was particularly enamored of the city’s stream valleys, including Herring Run and Gwynn Falls, and championed setting them aside as natural reserves.

“People struggled with that idea because they weren’t ‘parks’ in the way Druid Hill is a park,” says Orser. “Even now, not all people understand that these are parks.”

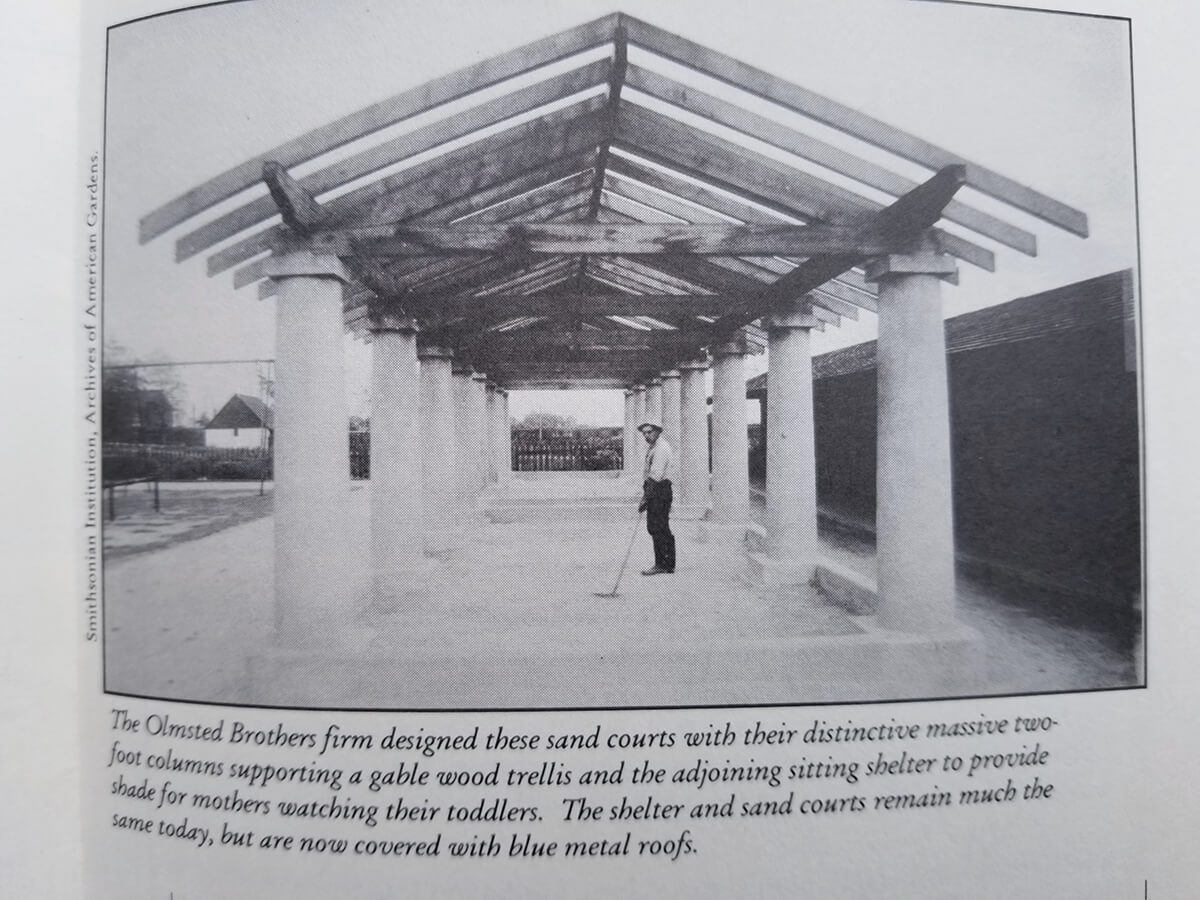

The report also shows how the world had changed from Olmsted Sr.’s time and the firm was adapting. At the turn of the century, the playground movement was gathering steam and residents wanted athletic recreation, not just Sunday strolls. Hence, the 1904 plan created the recreational extension of Patterson Park. At Latrobe, the design is quintessential Olmsted stuff, with many trees and grassy knolls, but the design also has a “men’s open-air gymnasium” and a “little children’s lawn,” complete with a shaded seating area for Victorian-era mothers.

“Latrobe is less than two blocks, but it is everything Olmsted in miniature,” says Orser.

The 1904 plan, only some of which was realized, was always about connecting larger parks, like Druid Hill and Patterson Park, with greenway networks and tree-lined boulevards as well as building small community parks, like Latrobe and Riverside, so residents could easily access the outdoors. Because of this vision, Baltimore lacks a problem other municipalities face.

“When I attend parks conventions, people often talk about the importance of access,” says Jennifer Arndt Robinson, executive director of Friends of Patterson Park and the current president of Friends of Maryland’s Olmsted Parks and Landscapes, Inc. (FMOPL). “That’s not our problem. Ours is about improving the quality of our parks, ensuring resources, and creating connections with communities.”

When Robinson moved to Patterson Park in 2001, she met folks who hadn’t set foot inside the park in 20 years. Thanks to neighborhood involvement, the park is now a lively place, but it was the COVID-19 pandemic, of all things, that proved to be the biggest boon. People took advantage of parks, including Patterson, as safe gathering spaces.

“Parks play a big part in public health—they did back then, and we see it now with the pandemic,” says Robinson. “How people use parks shifted in the pandemic,” she continues. “Before they may have gone for a run in the morning, but now they’re having picnic dinners there; parks are a part of their daily existence. People’s understanding of the roles parks can play in city living has been greatly enhanced.”

In fact, NAOP’s Petri says parks have been “loved to death” during the pandemic. Where once Robinson was focused on engaging people to use the park, she’s now trying to balance park accessibility with so many users. She also recognizes that much of the successful resurgence at places like Latrobe and Patterson Park is due to shifts in neighborhood demographics and subsequent investment. But what of the neighborhoods that have not seen similar upswings?

“Olmsted would be saying now is the time to look at areas where we have greenspaces that are being underutilized so those communities feel connected to their parks and neighborhoods,” says Robinson.

“LATROBE IS LESS THAN TWO BLOCKS, BUT IT IS EVERYTHING OLMSTED IN MINIATURE.”

Adam Boarman, PLA, is a licensed landscape architect and FMOLP member. He’s also chief of capital development for Baltimore City Recreation and Parks and knows a thing or two about the difficulties of maintaining the city’s more than 260 parks and approximately 4,600 acres of parkland, much with infrastructure that is over a century old. While almost every Baltimorean is within a 10-minute walk of a greenspace, many need some TLC.

This summer, Recreation and Parks embarked on a comprehensive plan and a citywide condition assessment of its parks to make data-informed decisions about where resources are best allocated. Maintaining existing parks is challenging enough. Creating new ones? Even harder. In 2020, a study was funded for The Baltimore Greenway Trails Network, which calls for a 35-mile “bike beltway” of urban trails linking neighborhoods and outdoor resources that takes inspiration directly from the 1904 Olmsted plan. And just as the entirety of the 1904 plan wasn’t fully executed, the Greenway is hitting resistance. Boarman says it’s a tough balance between equitable access to the outdoors and, say, ample neighborhood parking.

Perhaps that’s why preserving the Olmsted narrative is so important. Boarman notes that, particularly with the naturalistic aesthetic of Olmsted-like projects, it’s easy to overlook the intentionality of the design.

“My staff and I try to reference the history and the original intent of the design, no matter who did it, to honor and respect their vision, while also providing for modernization,” says Boarman. “It’s why Latrobe is so special,” he continues. “We’ve done our best to respect the original geometry and symmetry while adding things like the new field house and turf field, and the park is alive and well.”

The modern park movement isn’t without its successes. The Roland Park Community Foundation (RPCF) recently won its long battle to obtain 20 acres from the Baltimore Country Club. Though privately owned, it will be a public park, reportedly the largest to be created in the city in 100 years. RPCF has announced that “Hillside Park” will feature an Olmsted-inspired design, fitting given Roland Park’s existing Olmsted history.

Robinson says that, as a person who spends her days in Baltimore’s parks, she draws a lot of hope from Olmsted’s ideal of equitable greenspaces intimately tied to their communities.

“Baltimore has a lot of problems where money is not the answer,” she says. “Parks are one where serious investment could take away a lot of challenges. The city would change for the better. I see it every day with our youth workers, how their experience in and with the park changes their perspective. There’s so much possibility in our parks.”