Arts & Culture

New Book Explores Rise and Fall of America's Most Corrupt Police Force

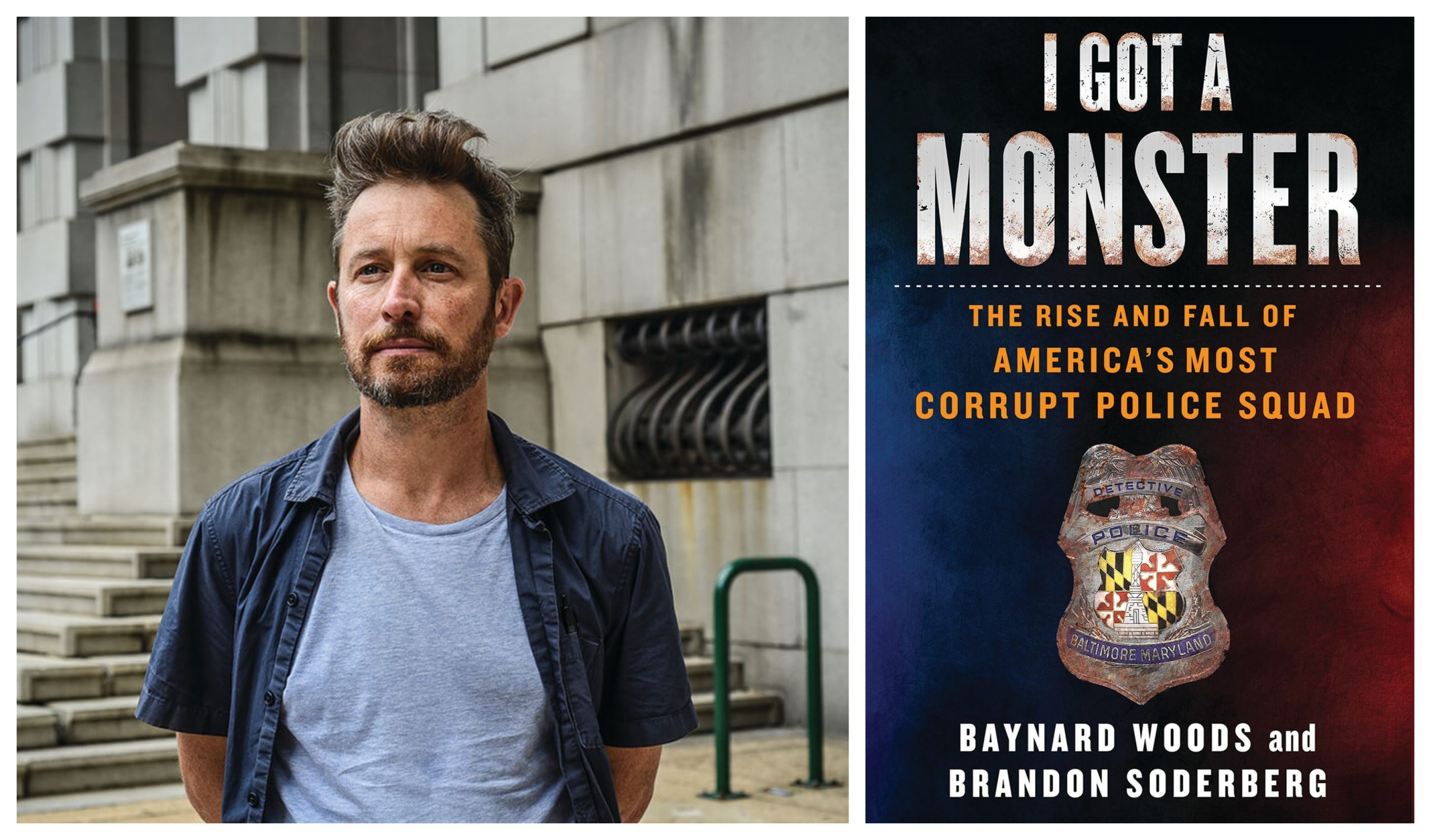

Baynard Woods and Brandon Soderberg discuss 'I Got a Monster.'

If Baltimoreans perceive the Baltimore Police Department’s now infamous Gun Trace Task Force (GTTF) as simply a bunch of bad apples skimming money and drugs, Baynard Woods and Brandon Soderberg set the record straight in their book, I Got a Monster (St. Martin’s Press), which is slated for a release on July 21. The crimes committed by the plainclothes unit, reconstructed here in stunning narrative detail, were part of an organized conspiracy of thievery, thuggery, and drug dealing.

The book’s title comes from sergeant Wayne Jenkins’ nickname for a big-time target—not to arrest, but as a potentially lucrative score for him and his crew. In the end, “monster” becomes an apt description of Jenkins, in particular, and the other six members of the Gun Trace Task Force, whom readers see prowling the city they have sworn to protect. Based on painstaking reporting culled from wiretapped conversations, jailhouse calls, body-camera and surveillance footage, court transcripts, and hundreds of interviews, it’s not just a must-read—it’s a page turner.

You both do an incredible job reconstructing the crimes of the Baltimore Police Department’s Gun Trace Task Force (GTTF). Why was it important to get the details down in print?

Baynard Woods: A lot of the details of GTTF corruption came out in the federal trial of the two former detectives who didn’t plead guilty—but those details came out piecemeal in testimony. We saw an immediate value in placing the events in chronological order so readers could [learn] something not only about their crimes but also about the context in which they took place—and [about] the human condition.

Do you think Baltimoreans realize this wasn’t just a group of corrupt cops, but a gang of violent criminals operating with impunity?

BW: One of the things we’ve learned over the past few years is that, yes, a lot of Baltimoreans knew this. They have been claiming that “BPD is a gang” for years. It’s mainly that white and middle-class Baltimore hasn’t taken those claims seriously. But I think everyone will be surprised at the details of their depravity.

Brandon Soderberg: The concept of “cops are a gang” is understood by plenty of people in the city, but the GTTF story really bears that out. It is not hyperbole with these guys. Actually, early on in the writing process I rewatched The Sopranos series because it helped me to think of the GTTF story as a gang/gangster story, not a police story. And these cops juggled domestic life, criminal life, and “straight” cop life so it was even more complicated for them than Tony Soprano.

How did Sgt. Wayne Jenkins and the others get away with robbing, planting evidence, and lying on affidavits for half a decade?

BW: It can’t be just a simple lack of supervision. During that time, the City was effectively waging war on its citizens. Politicians and police brass needed stats to show they were doing something about crime. Jenkins brought the stats and so, as in war, they looked the other way when he crossed the line.

BS: Jenkins and his squad gave command and other leaders in the city what they wanted: arrests, statistics. I think seizing guns and other things command could highlight and turn into good PR just made it easier to look the other way when these cops lied or stole. It’s like the locking them up was for the city, the robbing was for them. They also messed with people no one would believe: working people involved in the aboveground or underground economy. In Baltimore, those people are mostly Black and have been systematically ignored already.

In fact, the GTTF was not brought down by the Baltimore Police Department, but the DEA, correct?

BW: The U.S. Attorney’s would not have known about GTTF if the DEA had not been investigating a Black drug dealer in Northeast Baltimore. When he called Detective Momodu Gondo on a tapped phone, the feds realized there was something else happening. But it was finally the anti-corruption unit of the FBI that brought them down.

What was behind the behavior of the GTTF members? Simple greed? Power? A darker impulse?

BW: As always, people are complicated and I think everyone had their own reasons—but greed was the common denominator. For someone like Momodu Gondo, who was trying to protect his drug-dealing friends, I think loyalty was mixed with that. And for Wayne Jenkins, I think it was greed.

How does someone who didn’t grow up in, or doesn’t live in, one of the city’s chronically overpoliced neighborhoods begin to comprehend the GTTF’s calamitous impact—and general BPD behavior as documented in the DOJ investigation—on community trust of the police department?

BS: I think the easiest way to put it is that they created crime. By committing crimes themselves, but also because robbing drug dealers leads to violence (people get shot when the count isn’t right) and dealing drugs disrupts the underground economy. But also consider this: Tactics considered aggressive but still generally accepted in American policing foment chaos in communities, too. The GTTF were exceptionally bad, but we should make sure to see the GTTF as the not-that-surprising end result of decades of overpolicing.

Are you optimistic that the six-member Commission to Restore Trust in Policing, made up of lawyers, judges, and former cops, will put their finger on why and how the GTTF criminal enterprise flourished—and what can be done to make sure it never happens again?

BS: I was encouraged by the creation of the commission and it seemed to me like Senator Bill Ferguson had the right attitude. There were clear reasons why this happened and why it needs to never happen again. But the commission repeats some of the mistakes that enabled GTTF. The commission has not been transparent. It is headed by a judge, and includes three former cops, so it’s still cops investigating cops, and we know that doesn’t work. I hope that at the least we might get some public testimony out of this, which could be cathartic for the community.

The GTTF was disbanded after the federal criminal charges were brought, but plainclothes teams remain. Historically, plainclothes units have been problematic, but they have always been reconstituted, as you note in the book. Is there a better way?

BS: If we consider policing the answer to public safety at all, then plainclothes cops who are given a long leash and incentives to arrest anybody and everybody are not successful because they make the city less safe. So doing away with plainclothes policing is the beginning of a better way. Increase transparency because police understand how protected they are for sure. And divesting from law enforcement and giving more money to groups such as Safe Streets and other community-facing efforts would go a long way.

There’s also a documentary coming.

BW: As we were writing the book, we were simultaneously working with Alpine Labs, a production company, to film a documentary version, which is also called I Got a Monster. We really wouldn’t have had the time or resources to do the book right without them, and it also gave us a chance to tell the story in a different way. It was set to premiere at the Maryland Film Festival, which was postponed. We can’t wait for people to see it.