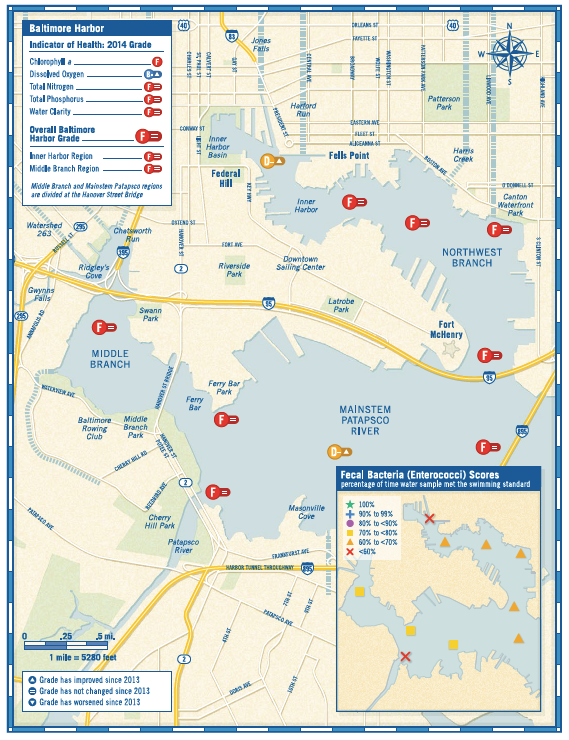

Waterfront Partnership board member Michael Hankin said he would’ve been grounded—”in his room”—if he’d ever brought home grades like the marks the Baltimore Harbor and its tributaries received on its annual report card Wednesday.

Released at a press conference today at the Marriott Waterfront hotel near the harbor’s innovative, year-old trash wheel, the overall water quality at the Baltimore Harbor scored an “F” in the 2014 report put together by the Waterfront Partnership and Blue Water Baltimore. The mark is a repeat of last year’s overall grade, but as Hankin and others noted, water quality in the Baltimore Harbor and two of three tributaries nonetheless made improvements in their scores. The Gwynn Falls stream, for example, is the first of the four distinct waterways measured—the Jones Falls stream, Baltimore Harbor, and the tidal portion of the Patapsco River are the other three—to receive a passing mark, albeit a D-minus, this year.

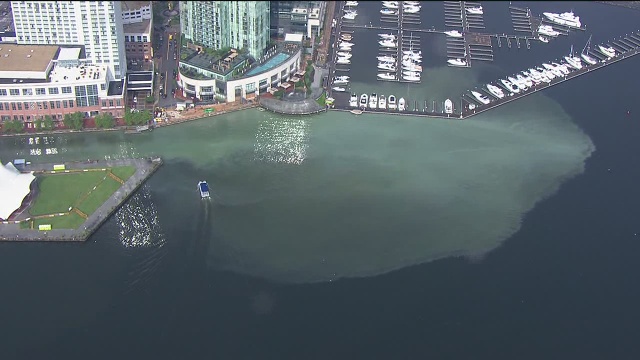

While the city has made strides with its expanded street cleaning efforts and stream restoration projects, and “Mr. Trash Wheel“—as the unique garbage collecting device in the Inner Harbor is known—has removed some 160 tons of waste since its installation last year, big challenges remain in terms of reducing stormwater runoff and sewage pollution. (Efforts are also underway, said Adam Lindquist, manager of the Waterfront Partnership’s Healthy Harbor initiative, to raise $500,000 and put a second trash wheel in Canton, across the street from the Boston Street Safeway, where the buried Harris Creek reaches and drains into the harbor.)

In 2014, Baltimore City reported 586 sewer overflows to the state Department of Environment, totaling 24.6 million gallons of sewage, according to the report. Those pollutants not only add fecal matter and bacteria to waterways, posing direct threats to human health, they can smother stream and river habitats, reducing oxygen levels and choking aquatic plant life and animals.

Based on the data, the Waterfront Partnership’s Healthy Harbor initiative is admittedly not on pace to make its goal of a “fishable, swimmable” Baltimore Harbor by 2020—a goal we examined in a story two years ago. Given the ongoing collapse of the city’s century-old sewer infrastructure, which director of public works Rudy Chow, also on hand Wednesday, has called “a ticking time bomb,” a drastic improvement in the harbor’s water quality isn’t likely in the immediate future.

Since 2002, the city has been under a consent decree, entered with the federal government and state, to complete a comprehensive wastewater rehabilitation program. The deadline to complete that overhaul is January 1, 2016—a date that the city is currently negotiating to push back. Chow said the studies and design plans for the estimated $1 billion effort have been completed and relining and replacement construction projects have begun. He would not estimate, however, the percentage of the overall work that has been completed to date, or speculate at the date of the expected deadline extension.

“I wish we could say the [sewer and other] infrastructure efforts by the city are making a difference, but we can’t say that yet,” David Flores, the Harbor Waterkeeper told Baltimore magazine. Noting the relatively short period covered since the first comprehensive harbor report card in 2012, Flores said, weather conditions, such as last year’s exceedingly cold winter, could be responsible for the recent, slight uptick in scores.

Progress reducing watershed run-off, more so than wastewater, may be more likely in the near future, given the passage of the so-called “rain tax” several years ago. The General Assembly last session, per Gov. Larry Hogan’s campaign pledge, did pull the requirement that the state’s 10 largest jurisdictions mandate a property fee to help reduce stormwater run-off—which carries chemicals, litter, road salt and toxins into waterways. But Baltimore City and the nine counties affected by the legislation are still required to find ways to pay and fund projects that reduce run-off and protect the health of the Chesapeake Bay, and by extension, the harbor and its tributaries.

“There’s a five-year timeline. By 2018, jurisdictions must remove or treat 20 percent of their impermeable cover,” Flores said. “It’s going to take millions of dollars to accomplish, but 20 percent is quite a substantial amount that will make an impact on water quality.”

Both the Waterfront Partnership—a group of private businesses, nonprofits and city agencies—and Blue Water Baltimore—which formed several years ago as a merger of several local environmental groups—also support efforts to ban plastic bags in the city and the state.

Last year, Baltimore City delegate Brooke Lierman introduced The Community Cleanup And Greening Act (HB 551), which would have prohibited the distribution of the disposable plastic bags statewide and placed a 10-cent fee on paper bags, but the measure failed to win support in committee. In Baltimore, Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake vetoed a plastic bag ban passed by the City Council last year. Lierman remains optimistic that with growing support the harbor can return to a healthy state.

“A couple of years ago, the Charles River in Boston hosted its first public swim in 50 years,” Leirman said. “I believe if Boston can do it, Baltimore can do it.”