ir

News & Community

Iron Pipeline

The high-capacity handguns fueling Baltimore's epidemic of violence increasingly enter the city through an underground network of out-of-state traffickers. Can anything be done to turn off the spigot?

THE FIRST TIME SOMEONE SHOT AT HIM, Kevin Shird was a tall, skinny 16-year-old. He’d been playing basketball when another kid he barely knew walked up and accused Shird of disrespecting his girlfriend. When the teenager reached for the gun in his front waistband, “dip” in Baltimore parlance, Shird chucked the basketball under his arm at him and ran. The next time someone pulled a gun on Shird, he was 17, and the target of a street robbery. When he was 21, a guy took a shot at him in broad daylight on West Fayette Street over a neighborhood beef. This time, he shot back.

Shird grew up in Edmondson Village. Not the easiest place to be a teenager. His father was a corrections officer and his mother worked at a department store, but raising four kids and paying for food, rent, and gas and electric bills was a lot to manage. Eviction was an ever-present threat. Sometimes the water got shut off. Getting three solid meals a day was a struggle at times, but getting a gun for protection wasn’t difficult at all. He’d known drug dealers since he was little, and he eventually went to work on a corner. His first gun was a .22 caliber Colt revolver, bought cheap from a heroin addict. Pretty quickly, he traded up to a .357 Magnum.

By 1992, in his early 20s, Shird was operating his own Diamond in the Raw drug crew in West Baltimore. The need for more guns, with greater capacity, had grown exponentially. He had to protect himself and his business, and six-shot revolvers no longer sufficed. Not with the semiautomatic Glock pistols—strong, lightweight handguns initially manufactured for the Austrian army and then heavily marketed in the U.S.— flooding the streets. The Baltimore police had already switched over from their service revolvers to semiautomatic Glocks in what was essentially becoming an arms race. Where did Shird turn for firearms? With a criminal record, he couldn’t legally purchase a firearm. No matter. The guns came to him and his crew.

Every few months, a burly man driving a nondescript sedan with North Carolina license plates would roll up to one of his Fulton Avenue or Mount Street corners. Not far from the Western District police station, in the neighborhood where Freddie Gray would be arrested a generation later, the North Carolina stranger would pop his trunk and display a cache of 12 to 15 semiautomatic handguns and ammunition. The man with the Southern drawl did a brisk business, accepting cash only from the highest bidders. The guys who moved the most heroin grabbed the prizes: 16-shot Glock automatics and, if their bankroll was big enough, body armor.

“It was all still in their boxes,” says Shird, who later did 12 years for drug trafficking. “We had an endless supply of Berettas, Glocks, 9mm handguns manufactured by Smith & Wesson. It got so you could place orders. Tell him what you wanted. Look, guns have always been easy to get in Baltimore, but if there’s one thing people have to understand, it’s that kids in Baltimore aren’t born with guns in their hands. Guns aren’t manufactured here. There aren’t even any gun stores left in Baltimore City to buy one legally. [There’s one, owned by an ex-cop.] All these guns—the cheap, broken ones, the ones passed around with a body on them, the ones traded for drugs, the expensive ones sold on the black market—they all come from someplace else.”

SHIRD TURNS 50 NEXT YEAR. During the Obama Administration, he served on the committee for the White House Office on National Drug Control Policy, as well as President Obama’s Clemency Project. He’s been a youth mentor, anti-gun violence advocate, and taught at Johns Hopkins University. He has published three books: a memoir, a well-received book about the ongoing civil rights struggle in this country, and one about the Baltimore Uprising. But the West Baltimore neighborhood where he’s from, and others in the city beset by gun violence, remain largely unchanged.

The Baltimore Police Department has pulled upward of 100,000 guns off the streets in the past three decades, an endeavor that has made no discernable impact on the accessibility of firearms. “A finger in the dike,” says former Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) special agent David Chipman, a Detroit native who earned his master’s degree in management from Johns Hopkins. It certainly hasn’t made any discernible impact on the epidemic level of gun violence, which has matched the record toll of Shird’s era over the past five years and taken nearly 10,000 lives in Baltimore since he was a scared 16-year-old kid. In fact, ask anyone close to the streets—a Safe Streets violence interrupter, a longtime Baltimore cop, a law enforcement official, an ex-offender—and they will tell you there are more handguns on the street, with higher capacity clips, than ever before.

It raises a vexing question: How does Baltimore, in a state with some of the toughest handgun purchasing requirements in the country, manage to produce the highest gun homicide rate of any large city in the United States?

The short answer: Nearly two-thirds of guns associated with crime in Baltimore come from out of state. And Maryland overall now has the highest rate of out-of-state crime gun “imports” in the country, according to a 2020 analysis of tracing data from the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. Traffickers today bring nearly three times as many firearms into Maryland as the national state average, playing a deadly role in Baltimore’s epidemic of gun violence.

As Shird’s recounting of the North Carolina trafficker makes clear, out-of-state guns have always been illegally sold on the streets in Baltimore. But in the past, out-of-state firearms accounted for a minority of recovered crime guns in Maryland—38 percent, 20 years ago. What’s changed—the unfortunate consequence of the strict gun licensing legislation passed under former Gov. Martin O’Malley in 2013—is that out-of-state guns for the first time represent a majority, a solid 54 percent, of Maryland crime guns traced by the ATF. More than 1,000 crime guns recovered in 2019 traced back to Virginia alone. Another 2,500-plus came from other jurisdictions, including Pennsylvania, the Carolinas, Georgia, West Virginia, and even as far away as Texas.

“We know from the data these guns mostly flow up the I-95 corridor—‘the Iron Pipeline’—because southern states have fewer restrictions on gun buying,” says former ATF chief of crime gun analysis Joseph Vince, a sociology and criminal justice professor at Mount St. Mary’s University. “Take any city that only deals with ‘bad guys with guns’ and spends 98 percent of their time on street arrests—there will always be more guns, and inevitably more ‘bad guys with guns,’ because so many young guys are in the drug trade. It doesn’t mean you don’t arrest everyone illegally possessing a firearm. You do. It means working both ends of the equation. Otherwise, the guns keep coming. This should not come as a surprise to anyone in law enforcement, but it often does.”

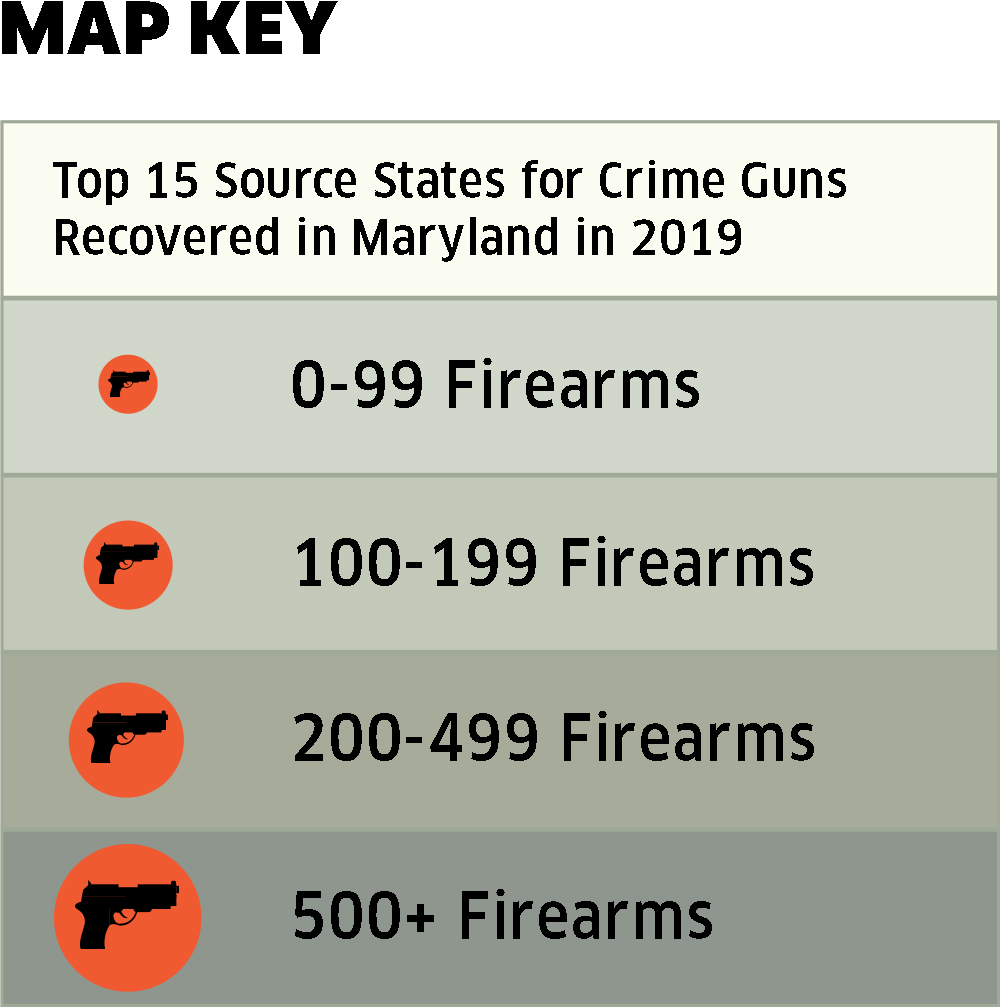

Out-of-State Gun Trafficking Data

The source state of crime guns recovered in Maryland was identified in 6,543 traces in 2019. The majority of those guns—3,525—came from outside Maryland.

—Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives

Map by Curt Iseli

GUN TRAFFICKING PATTERNS remain remarkably consistent year to year and state to state. Just as the biggest exporter of crime guns into Baltimore is Virginia, which has less restrictive guns laws than Maryland, the lion’s share of the out-of-state guns recovered in Chicago originate in Indiana, where it’s easier to buy a firearm than Illinois. Similarly, in Los Angeles, hundreds of guns each year trace their point-of-sale back to Arizona, where it’s much easier to purchase a handgun than California.

Yet, the path of crime guns within the Iron Pipeline—from retail establishment of origin to the underground gray and black markets—is varied and loose. There’s no overarching criminal conspiracy. Some are stolen after they’re legally purchased and used in crimes. Other guns associated with crimes are claimed to have been “lost” by previous owners once they’ve been recovered and traced. A small but fast-rising number of crime guns in Baltimore (51 through September) are so called “ghost guns,” firearms legally made from mail-order kits without serial numbers and resold on the street—again, mostly from sources outside the city. Still others are diverted from the legal market through out-of-state gun show loopholes and private sales, deals that avoid the federally mandated back-ground checks for commercial purchases, as well as the federal 21-year-old age requirement to purchase a handgun. “The age requirement is no small thing when you look at the number of 18-, 19-, and 20-year-olds who commit gun violence,” says Daniel Webster, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Prevention and Policy. “In terms of private sales, if you live in West Virginia and you see someone selling a gun online, you can make arrangements to meet in a Walmart parking lot and buy it. Then, you resell in Maryland.” A new semiautomatic Glock 19 that goes for $600 can net a couple hundred dollars of profit on the Baltimore streets.

Last fall, two young Virginia men admitted in court to trafficking 45 firearms in Washington, D.C., and Maryland to people willing to pay marked-up prices because they couldn’t legally buy guns themselves. At least 17 of those weapons have already been recovered as part of other criminal investigations, according to reporting by The Washington Post, including one murder.

Some firearms are illegally obtained from a tiny but real fraction of rogue gun and pawn shops that make “off-the-record” sales. These backdoor buys occur in Maryland, according to a recent Johns Hopkins survey of ex-offenders, and in other states. Talk to an ATF official, and they’ll tell you it can take a half-dozen years to revoke the license of even the worst gun dealers. It took nearly a decade to revoke the license of Sanford Abrams, an outspoken gun advocate who once served on the board of the NRA and formerly owned Valley Guns in Parkville. In one 15-month stretch in 2006 and 2007, for example, 108 guns used in Baltimore crimes were traced back to his store, which was ultimately cited for more than 900 bookkeeping violations.

Dante Barksdale of Safe Streets in front of a mural near their East Baltimore office. Photography by Joe M. Giordano.

THERE IS NO EVIDENCE, however, of a concerted effort by local gangs to skirt Maryland’s gun laws by venturing to Virginia, the Carolinas, Georgia, or other states to traffic firearms into Baltimore. Too much trouble and too risky. Those involved in tackling gun violence in the city, at the Department of Justice, ATF, and Baltimore Police Department, say it’s overwhelmingly out-of-state traffickers who bring weapons to Baltimore for resale. Those not in law enforcement, including the city’s defense attorneys and violence interrupters, say the same.

“We can round up 100 of these young guys [potential gun buyers] in Baltimore, and I guarantee you, 90 of them don’t have a driver’s license, and of that, 10 or so, maybe five have access to a car,” says Dante Barksdale, the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice outreach coordinator of Safe Streets and an ex-offender who previously served prison time on drug and gun charges. “In Baltimore, 13-year-olds are like 19-year-olds, but 30-year-olds are also like 19-year-olds—most of these dudes barely make moves from East Baltimore to West Baltimore. Most have never been to Washington, D.C.,” Barksdale continues during a walk outside the Safe Streets office on East Monument Street while gesturing to a group of young men in McElderry Park. “They are not driving to some neighborhood they don’t know in Georgia to buy guns. And then what? Driving back on I-95, waiting to get pulled over?”

In 2015, a firearms network that brought more than 400 weapons from Tennessee to Baltimore was broken up by federal law enforcement and the BPD, but that kind of large-scale operation is extraordinarily rare.

Many people, including police officers, assume most crime guns are stolen, but it’s a misconception. Only an estimated 10 to 15 percent of recovered crime guns are stolen, typically from the homes of family members and friends by those struggling with addiction and then sold to buy drugs. What is true is that an increasing number of firearms are stolen from brick-and-mortar gun shops.

Unlike pharmacies, which must adopt security measures to prevent theft, gun-shop owners are under no similar obligation to keep their inventory out of the wrong hands. It’s a weakness in the system not lost on traffickers. Between 2012 and 2017, more than 32,000 firearms were stolen from gun dealers. Burglars hit a record 577 gun shops in 2017, a 70-percent increase over the four previous years, with predictable consequences.

One stolen gun from that period, a 9mm Ruger, from a group of 74 stolen in a burglary of a North Carolina gun shop, was used to murder 36-year-old Harry Davis Jr. in Baltimore. Shortly after a Mother’s Day cookout in 2015 with his wife and son, Davis was killed near his Woodmere home.

Notably, the top out-of-state sources for crime guns recovered in Maryland also top the list for guns stolen from licensed dealers. Texas, Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina all rank in the top five. Closer to home, gun shops in Baltimore County were burglarized 10 times in 2018 and 2019, including one incident in which 51 weapons were lifted. In June 2019, burglars hit firearm retailers in Howard and Montgomery counties on successive nights, ramming each retailer with a car and stealing a total of 45 weapons. Only four states—California, Connecticut, Minnesota, and New Jersey— have enacted state laws requiring gun stores impose anti-burglary measures.

All that said, the most likely way crime guns begin their ill-fated journey is through what’s known as a straw purchase, a criminal act in which a firearm is bought by one person on behalf of someone who is legally unable to make the purchase themselves from a legal firearms dealer. How many gun dealers are, wittingly or unwittingly, complicit is anyone’s guess.

Currently, more than 56,000 individuals possess federal licenses that allow them to act as firearms dealers across the country, and another nearly 8,000 have licenses that allow them to buy and sell guns as pawnbrokers. Together, that’s more than the combined number of Starbucks, McDonald’s, and Subway franchises in the U.S. The vast majority of licensed dealers are completely law-abiding, but a group of federal prohibitions known as the Tiahrt Amendments (named for former U.S. Rep. Todd Tiahrt, R-Kansas) significantly restrict law enforcement’s ability to investigate gun crimes and prosecute unscrupulous gun dealers. Those amendments also prevent the disclosure of data to members of the public, journalists, researchers, legislators, and would-be litigants, too, for use in any lawsuits against the gun industry.

“Without doubt, there are bad gun dealers who turn a blind eye,” says Chipman. In 2013, Maryland passed legislation that targeted straw purchasers by ratcheting up the state’s already tough rules by requiring classroom training, fingerprinting, a demonstration of safe use, and background checks to obtain a license to buy a firearm. It also placed a ban on assault weapons and magazines that hold more than 10 bullets and prohibited any person from purchasing more than one handgun or assault weapon within a 30-day period.

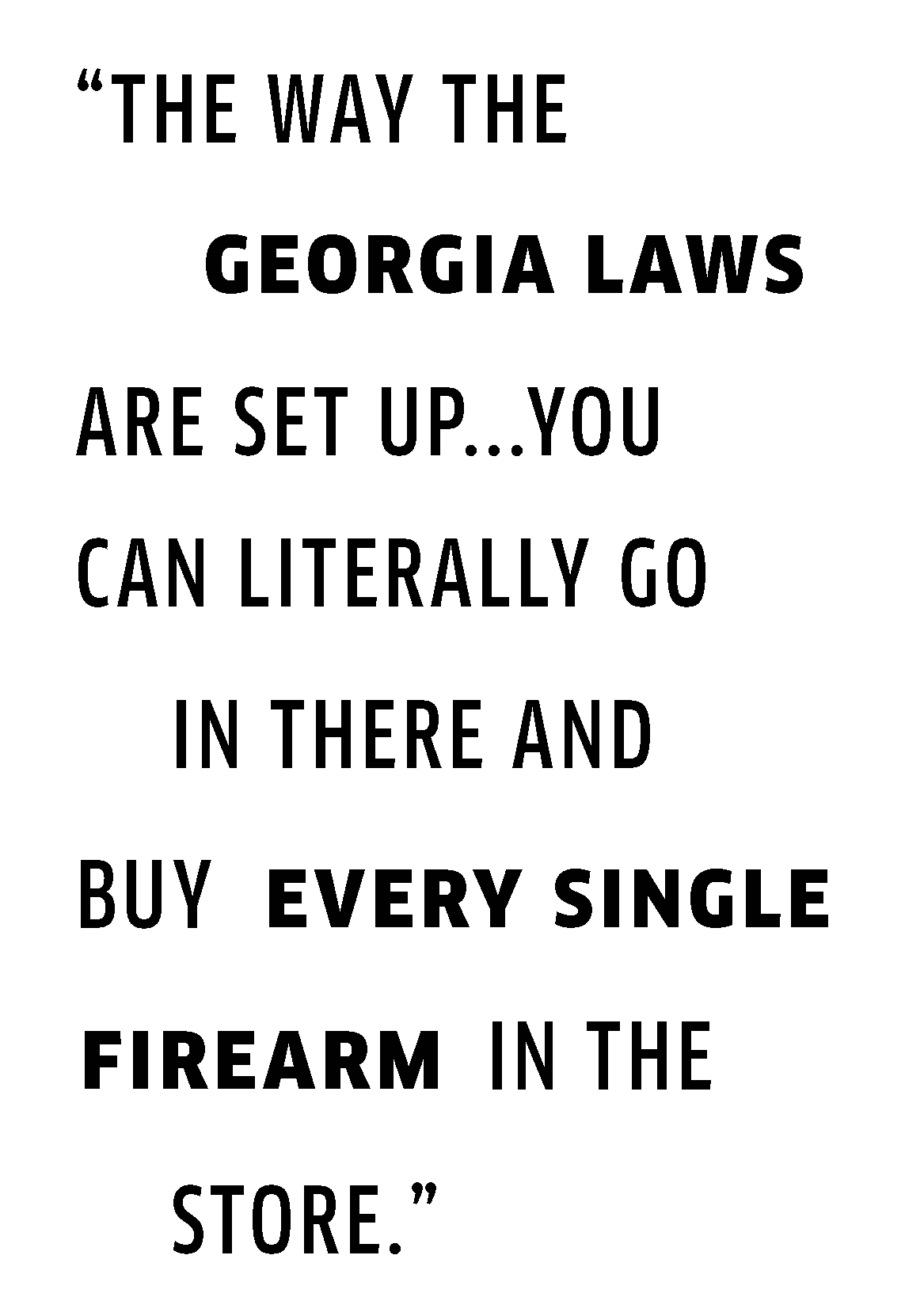

Overall, it simply puts Maryland in a much different category than states to its south, which largely have been rolling back restrictions—think open carry laws. Virginia, which recently switched from red to blue, is an exception and did put new restrictions in place this summer.

“The way Georgia laws are set up,” says Timothy Jones, Special Agent in Charge of the Baltimore region, formerly of Georgia, “if you have the money and you have a valid driver’s license and can pass [an instant background check], you can literally go in there and buy every single firearm in the store.”

What does straw purchasing look like? Sometimes, it’s teenagers going to a gun shop with someone older with a clean record who will buy a gun for them, for a price. It’s not dissimilar, if infinitely more dangerous, from someone older buying alcohol for a teenager. Often, straw buyers are women making a purchase for a boyfriend or male family member. “I’ve seen camera surveillance where guys go into the gun shop, pick out exactly what they want, and then give it to their girlfriend and let her fill out the paperwork,” says Chipman, who began his ATF career in Tidewater, Virginia, an area that sends guns to Baltimore. “I’ve seen women go into a shop and text photos of guns to their boyfriend, who was sitting in a car in the lot, to make sure she’s buying the right one.”

When a woman buys a gun for someone, that gun is twice as likely to be involved in a crime.

“When we think about who the straw buyers are, often he’s a she,” says Nancy Robinson, who runs the Boston-based Citizens for Safety and launched the initiative Operation Lipstick (Ladies Involved in Putting a Stop to Inner-City Killing) several years ago, which has since expanded to New York, Philadelphia, and Oakland. It aims to disrupt the flow of guns by appealing to the women who buy, hold, or hide guns for men—often also their abusers. “Just like woman are prey for drug dealers and sex traffickers, it’s a woman who’s being exploited regarding illegal guns,” Robinson says. In Baltimore, women are also increasingly the victims of homicides (37 last year) and shootings (87 in 2019). Earlier this year, a 23-year-old Virginia woman pleaded guilty in Alexandria federal court to buying 31 guns for her Maryland boyfriend.

“Where did the gun come from?” Robinson says, “should be the response to every shooting.”

Arrowhead Pawn in Georgia sold the gun that a Baltimore man used to kill two New York police officers. Photography by Kevin D. Liles

IN 2007, UNHAPPY WITH the police department’s results, then Mayor Sheila Dixon fired Chief Leonard Hamm and tapped Deputy Commissioner Fred Bealefeld for the job. Bealefeld is widely credited with the subsequent dramatic decrease in gun homicides. It’s a tenure that five police chiefs since have been unable to replicate. With 26 years on the force, Bealefeld wanted to know the same thing Robinson did: Where did the guns come from? How did they get onto the city’s streets? Bealefeld still remembers James Smith III, a 3-year-old killed by stray gunfire as he sat in a Hollins Market barber chair in 1997. He’d felt certain at the time the tragedy would spark gun reform. It didn’t happen, of course. Bealefeld was also familiar with Webster’s research at Hopkins, since repeated in other studies, which showed that if you turned down the spigot of crime guns at their source—creating a licensing process and weeding out “bad apple” gun dealers—you could reduce illegal access to firearms. Fewer guns, demonstratively, meant fewer gun deaths.

Bealefeld had been chief of detectives and took a wide view of gun violence. He understood that previous administrations’ celebration of drug seizures and accompanying media photo ops were misleading and that the same thing was now being done with the “war on guns,” which targeted “trigger pullers” and played up street-level gun seizures. “Guys got recognized for the number of guns they pulled in. The focus was ‘guns, guns, guns, guns,’ but it wasn’t getting us anywhere,” Bealefeld says. “In Baltimore, through the 1990s and into the 2000s, we seized 3,000 to 4,000 guns a year. We weren’t alone in that either. We did the gun buy-backs, too, which are more of a distraction than anything. What I learned is that we can’t come out ahead that way. We’d seize 8,000 guns in the state, counting Prince George’s and the other counties, but 20,000-30,000 new handguns are sold each year in Maryland. That’s not including the guns from out of state. The notion that you could seize all the guns and dry up the supply seemed to me to be futile.”

Almost immediately after taking over, Bealefeld created the small-unit Gun Trace Task Force, which would become—after his departure and once it strayed from its original mission—infamous for its street rips, robberies, drug selling, and corruption.

At its inception, the Gun Trace Task Force was tasked with following recovered crime guns to their place of origin. It collaborated with the DOJ, ATF, state police, and law enforcement from surrounding counties. “Initially, we were doing what we were supposed to be doing, tracing guns to their source,” says a former BPD lieutenant and original member of the task force, who has since started a new career and wishes to remain anonymous. “If we recovered a gun associated with a crime that had a suspicious history and a serial number, we’d track down the person who’d bought it from the gun or pawn shop. I remember once, because I looked it up, the same guy purchased the same model handgun—legally, he didn’t have a record—12 times, every month or so. No one does that. So I went and knocked on his door. He invited me in and showed me his safe, which was basically empty, and said he ‘didn’t know what happened to them.’ He was selling them when he needed some money.

“It’s easier to arrest an 18-year-old Black kid with a gun on the street, so that’s what cops do.”

After Bealefeld resigned in May 2012 to spend more time with his family, his replacement, Anthony Batts, commissioned a strategic review of the department. Overseen by William Bratton, the former L.A. and New York City police commissioner and an advocate of “stop-and-frisk”-style policing, that report—not surprisingly—dismissed the Gun Trace Task Force efforts as “largely administrative work on guns” and questioned its priorities, suggesting a return to “productivity” and making arrests. Already lacking supervision by 2013, the unit went entirely off the rails, yet kept earning kudos for street gun seizures. The criminal misdeeds of the GTTF, well chronicled by Baltimore Sun reporter Justin Fenton, and former City Paper journalists Baynard Woods and Brandon Soderberg in their recent book, I Got A Monster, don’t just highlight rampant corruption in the Baltimore Police Department, but indicate a massive failure of strategy.

Today, Bealefeld would like to see purchasing requirements on the sale of ammunition, which doesn’t require a license to buy or a sales log and isn't regulated in any way by the Maryland State Police. He’d also like to see the statute of limitations raised on secondary gun transfers.

“I’ll tell you something astounding,” Bealefeld says, sharing an illustrative story about the department’s often short-sighted practices. “When the department switched over from its service revolvers to Glocks, it sold the old revolvers to local gun shops. Do you know what happened? We started recovering those revolvers at crime scenes. They still had the stamp, ‘BPD.’”

Erricka Bridgeford conducts a Ceasefire 365 prayer ritual, burning sage at the scene of a recent West Baltimore homocide. Photography by Joe M. Giordano

A 2014 STUDY OF MISSOURI by Webster and fellow Hopkins researchers predicted what we’re seeing in Maryland, in terms of the flow of interstate gun trafficking. When the state required buyers to get a permit and undergo background checks on private sales, two restrictions strongly associated with reducing the number of guns in the illegal market, the number of guns coming from outside Missouri rose to nearly half, with most traced to neighboring Kansas and Illinois, which have weaker laws.

Webster’s subsequent work showed that if neighboring states tightened their gun laws, it could reduce the homicide rate by 25 percent or more. In Baltimore, that could correlate to 75 lives a year. Overall, states with weak gun purchasing requirements rank highest in gun homicide rates, including Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Georgia. Maryland, surrounded by states with weak gun laws, is the anomaly, ranking fifth.

“It’s not that gun laws aren’t effective; they are,” says former ATF agent Chipman, advocating for national legislation. “It’s that they are piecemeal. It’s like pollution: State borders are porous, you need the EPA.”

Frustrated by the lack of national legislation and federal law enforcement help in the mid-2000s, then New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg sued 27 gun shops in the south that were feeding guns to the city. Specifically, the aim of the lawsuits was to prevent straw purchases at a time when nearly all of the guns used in New York City homicides were coming from out of state. Nearly all of suits were successfully settled in New York’s favor with targeted dealers agreeing to have their operations overseen by a court-appointed special inspector. A Johns Hopkins study of seven dealers that settled lawsuits with New York found a 75 percent decrease in those dealers’ portion of crime guns that ended up on the city’s streets shortly after sale. Additionally, in 2007, New York saw an overall 16 percent decrease—a deterrent effect—in the number of crime guns coming into the city from the five states where they sued gun dealers. Bealefeld said he watched from afar what New York was doing and hoped it would have some positive collateral impact here. But he added that Baltimore did not have the resources to launch a similar legal campaign.

Public will does exist for reform. Last year, Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers found wide agreement among gun owners, non-gun owners, and across political parties for stricter gun policies, including purchaser licensing (77 percent) and universal background checks of purchasers (88 percent). It’s interesting—and perhaps counterintuitive, given the open-carry displays of weapons and rollback of gun laws in many places—the number of American households with guns has dropped from 50 percent in 1977 to 30 percent today. Conversely, gun manufacturing has tripled since 2001. In other words, fewer people own guns, but those who do buy a lot more.

No one suggests greater gun restrictions is a panacea. There’s no single answer to the multilayered gun violence problem. Webster and others continue to stress a holistic approach—poverty reduction, police reform, youth intervention, to name a few—remains necessary. “But stopping the bleeding is important,” Webster says. “We should be doing what’s most efficacious. Shootings hurt a neighborhood’s economic development. It hurts families. The trauma hurts kids’ performance in schools.” Many of those working on the grassroots level in Baltimore remain skeptical that broad, effective gun policy will ever be implemented and enforced.

Considering how ubiquitous guns have become in the city, it is understandable.

“I assume everybody I meet has a gun,” says Erricka Bridgeford, the Baltimore Community Mediation Center director and Baltimore Ceasefire 365 cofounder. “People get guns for protection, not intending to hurt anyone. It’s the outcome of our policies. We’re so busy policing people, we don’t do anything that actually improves their circumstances or makes the city safer.”

Chipman, the gun-owning former ATF special agent, is blunt in his assessment of the gun industry and its hold on the Republican lawmakers on Capitol Hill, where, for example, the ATF budget has remained flat for 30 years, despite the explosion in arms sales. He’s clear the industry is not about to relent in its opposition of stricter gun policies. “Violence is their selling point,” he says. “The more violence, the greater the fear of violence, the more guns they sell.”

When the opioid epidemic exploded into white communities, legislators and law enforcement eventually began prosecuting doctors who were conspicuously over-prescribing drugs and the pill mills masquerading as pain clinics—and later went after the pharmaceutical industry. But few believe a similar proactive turn regarding gun violence is likely as long as gun homicides in Baltimore and elsewhere so disproportionately impact young Black males, in particular. Meanwhile, with the ongoing pandemic and overall political strife, Americans bought nearly 17 million guns in the first nine months of 2020, already more than in any other single year. An increase in gun purchases in just the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with a nearly 8 percent increase in gun violence in the U.S., according to researchers.

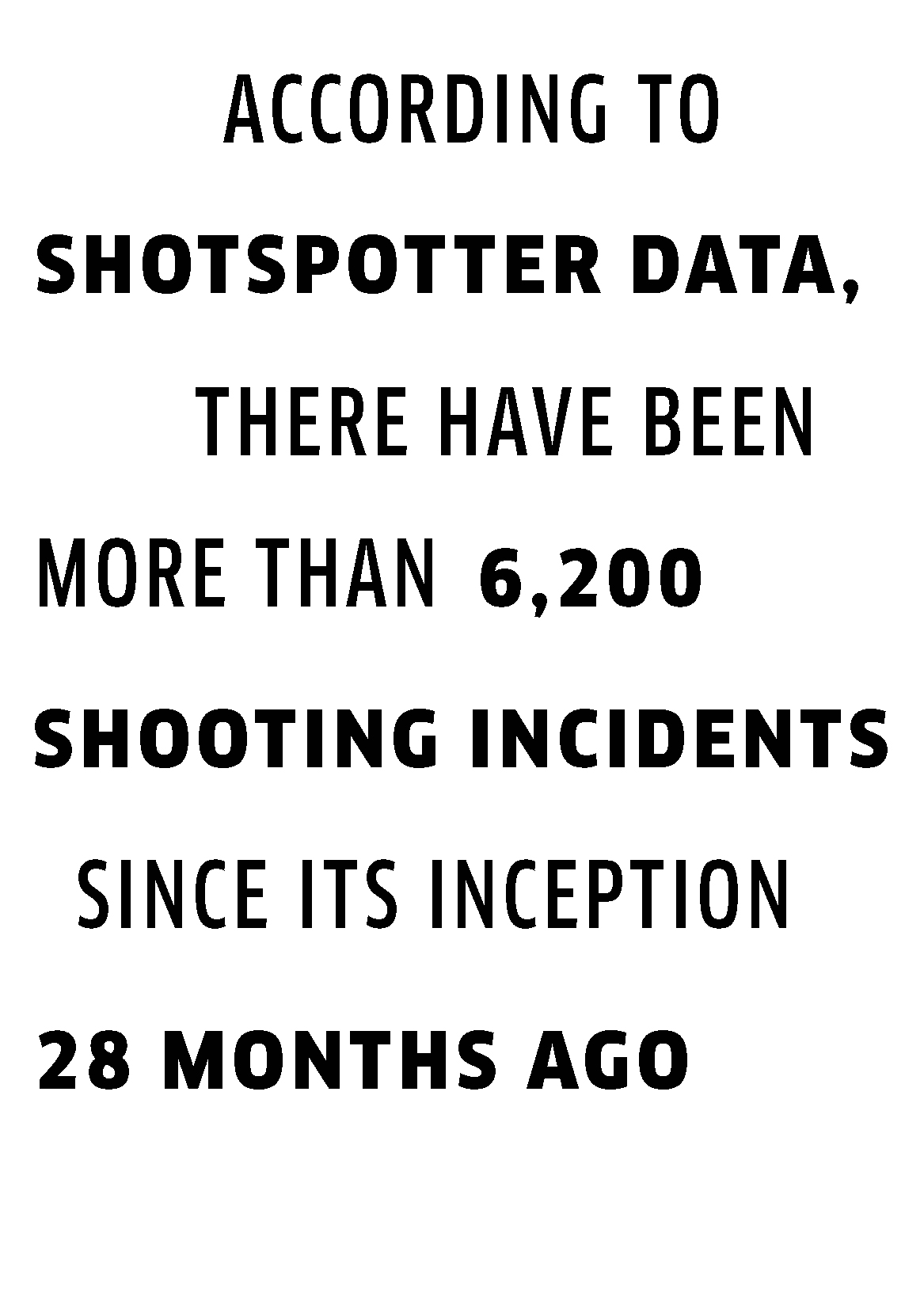

Consider for a second the full scope of fear and trauma from gun violence in some of Baltimore’s neighborhoods. It’s not just that there were 322 gun homicides, 28 gun suicides, and 771 shooting victims last year in the city. According to ShotSpotter data, which only covers the city’s very highest-crime areas, there have been more than 6,200 separate shooting “incidents” in the first 28 months since its inception in 2018. Translated, it means there are numerous incidents when shots are fired but no one is hit, as was the case with Shird. It’s a good thing, but hardly comforting.

Activist Duane Davis, an ex-offender, doubts genuine gun reform is likely. “People I know refer to Baltimore as ‘Little Palestine,’” Davis says. “With the helicopters, ‘spy’ planes, cameras everywhere, we already live in a surveillance state. As long as the killing remains inside of that surveillance, those in power won’t do anything.”

Todd Cornish, an ex-offender who works with a local arabbers stable, makes another, similarly pessimistic, analogy.

“Anywhere there is strife or civil war in the world, the United States sends its arms,” Cornish says. “Sometimes we sell them to both sides. You don’t think people in West Baltimore understand that? West Baltimore, East Baltimore, some of these neighborhoods, they are war zones. Why would anyone believe the weapons are going to stop coming?”

RON CASSIE is a senior editor at Baltimore.