News & Community

The Passion of Sheila Dixon

The former mayor would like her old job back, but is Baltimore ready to forgive her?

It’s 2 p.m. on Sunday, September 13, and hundreds of Baltimoreans are streaming into the B&O Railroad Museum. Dressed in everything from church clothes to jeans and T-shirts, they breeze past the gift shop, through the historic roundhouse, and outside to the reception pavilion, which is set up for a party with a sundae bar at one end, a DJ booth at the other, and a stage in between. But even the sundae bar’s four flavors of Jack & Jill ice cream and the upbeat strains of Whitney Houston, Bruno Mars, and The Black Eyed Peas are no match for today’s star attraction.

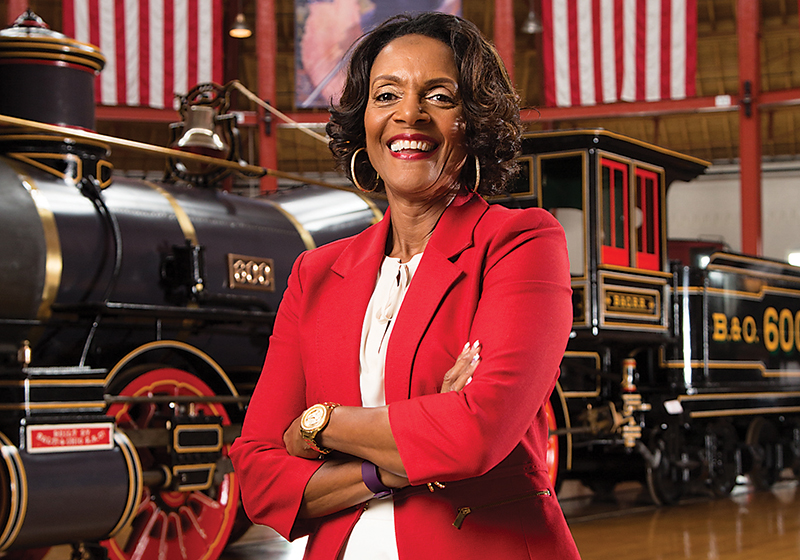

The real reason people came today is standing outside the pavilion’s entrance, dressed in a white ankle-length dress, red blazer, and stiletto pumps. Former mayor—some might say disgraced former mayor—Sheila Dixon is here literally shaking hands and kissing babies, as some 400 supporters pour in for her ice-cream social campaign event. Though Dixon announced she was running to reclaim her old job back in July—and has been hinting at her interest for even longer—this is being billed as her campaign kickoff. It’s her first step toward the Democratic mayoral primary on April 26, and then, if all goes according to plan, the general election a year from now.

Though she still has a long way to go, there is an extra buzz amongst the crowd today; the air feels different. Partly this is literal—a cold front swept through yesterday, pushing out the oppressive heat of summer and replacing it with the gusty coolness of fall—but it’s also figurative. On Friday, Dixon’s successor, Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, announced that she would not seek re-election. In light of that bombshell, Dixon’s campaign suddenly seems less like a curiosity (“Baltimore Is Getting Out the Popcorn for Sheila Dixon vs. Stephanie Rawlings-Blake” blared a Baltimore Business Journal headline in July) and more like a real option in a crowded field. Indeed, if the event’s turnout and media profile are anything to go by, Dixon may now be a—if not the—front-runner. Even City Council president Bernard “Jack” C. Young—once rumored to be considering a mayoral run himself—has stopped by to glad-hand prospective voters.

You can tell Dixon feels the momentum as she mounts the dais, looking a good decade younger than her 61 years. She begins her remarks by thanking her many loved ones in attendance—including her two children Jasmine, 26, and Joshua, 20—and wishing happy birthday to several close associates. She then launches into a speech that will be familiar to anyone who has seen the campaign video she unveiled just a day later. She characterizes Baltimore as “smart, tough, and strong”; lauds its citizens as “our greatest asset”; and promises to “reclaim, revive, and rebuild this great city.” But there are hints of a more complicated history here, too. More than once, she emphasizes her experience, and, in the video, she talks about Baltimore’s capacity for “second chances.”

“Clearly, I disappointed people. I was embarrassed. I was devastated.”

Outside the museum, Rick Black, an accountant from Northwest Baltimore who is challenging Dixon for the Democratic nomination, stands with three volunteers, attempting to siphon interest away from the fundraiser. When asked why he is running, his answer is a reminder of all that has gone unsaid today. “We shouldn’t be saddled with a thief for mayor,” he says. “You can’t trust a thing she says.”

Dixon was still City Council president in 2006 when the state prosecutor began investigating her for potential ethics violations, including voting on contracts that benefited her sister’s employer and employing friend and campaign chairman Dale G. Clark without a contract. Though these allegations never resulted in any charges, the sprawling probe continued to home in on Dixon, especially her dealings with developers. In early 2009, Dixon, now mayor, was indicted on 12 charges (five of which were eventually dismissed) that included felony theft, perjury, fraud, and misconduct in office. The resulting trial revealed details about gifts lavished on her by Ronald Lipscomb, a married developer whom she briefly dated, as well as details about a sort of gift card slush fund she had set up for the needy, to which developers looking to curry favor would donate, and from which Dixon was found guilty of misappropriating about $630 worth of cards for personal use. (Dixon maintained that she thought the gift cards in question were gifts from Lipscomb.)

Already convicted of one misdemeanor and facing a second trial for a remaining offense, Dixon accepted an Alford plea deal on a perjury charge—meaning she did not admit guilt but acknowledged a jury could have convicted her based on the evidence. She was required to complete four years of probation, perform 500 hours of community service, and make a $45,000 charitable donation. In return, she would have no criminal record and would keep her $83,000-a-year government pension. But she had to resign as mayor, which she did, reluctantly, at noon on February 4, 2010.

For some, like Rick Black, this is all they remember about Sheila Dixon, and nothing will ever wipe the slate clean. Forget the creation of the free Charm City Circulator bus system. Forget single-stream recycling. Forget all the roads resurfaced as part of Operation Orange Cone. Forget the construction of the city’s first 24/7 homeless shelter. Forget the 20-year low in homicides under the steady leadership of Fred Bealefeld, whom she championed as police commissioner despite enormous political pressure. She is simply a crook, a liar, and a disgrace.

Robert Rohrbaugh, the now-retired state prosecutor who led the Dixon investigation is just as blunt as Black when describing Dixon’s political re-emergence. “Ms. Dixon has every right to seek political office and, in my opinion, the voters have every right to reject her,” he writes via email.

But in between the Rick Blacks and Robert Rohrbaughs of the world and her adoring public, there are voters watching Dixon’s comeback with some vague mixture of interest and unease. They accept that she may have been a good mayor, but they’re not sure she’s a good person. They want to know, who is Sheila Dixon and can they trust her?

About a week after the ice-cream social, Sheila Dixon is alone in her tiny street-facing office at the Charles Village headquarters of the Maryland Minority Contractors Association, where she has been employed since mid-2010. It’s 9 a.m. and, like most days, she has a full schedule ahead of her. Though her title is marketing director, she is, to hear her describe it, more like an executive director, involved in almost every aspect of the organization. It seems she can’t help but run things.

Impeccably fit and well dressed, she is guarded, but radiates an earthy warmth despite her wariness. She dutifully answers questions as we plot the familiar biographical arc, starting with her childhood in a working-class West Baltimore family, then moving along to her education at Northwestern High School, Towson University, and finally The Johns Hopkins University, where she earned her master’s in education management. She touches on her time as a teacher for the city school system, her 17 years as an international specialist for the Maryland Department of Business and Economic Development (now the Department of Commerce), and her deep involvement with her church, Bethel AME, renowned as the place of worship for Baltimore’s African-American power elite.

But it is when she begins talking policy that she comes alive. Whatever else Dixon is, she is truly interested in the mechanics of running a city. “When I got on the [city] council,” she says, “I began to learn city government, learn the budget process, learn the different aspects and the agencies. I was fascinated because I wanted to know how those things worked, so I could do my job even better.”

Her political career started in earnest in 1987 when she won a seat on the City Council, representing much of West Baltimore in what was then the 4th District. “I remember [then Mayor Clarence H.] Du Burns saying, ‘Just don’t get in there and get up and give flowery speeches. You’ve got to get out there and do for your district,’” she says. “And when I went around in my district and saw so many challenges and issues that had not been addressed—I mean, that was the driving force.”

In 1991, she had her first brush with infamy after she took off her shoe and banged it on a table in anger during a council meeting. She shouted at white colleagues, “You’ve been running things for the last 20 years. Now the shoe is on the other foot.” Known as “the shoe incident,” those few seconds branded her as combative and provided plenty of ammunition for those who wanted to reduce her to the offensive “angry black woman” stereotype. It wasn’t until an interview with The Sun eight years later—in the midst of her campaign for City Council president—that she addressed the incident in any detail, explaining that her fury was stoked when a white colleague made bigoted remarks in a closed session before the meeting. The comments, she said then, were like “fighting words, like talking about somebody’s mother.” And yes, it did make her angry. “I was so angry that I was gonna take off my shoe and smack [the white colleague] in the head,” she told The Sun. “And the [TV] cameras were on me and I caught myself, and [Councilwoman] Vera Hall came over and said, ‘It’s not worth it.’ And that’s when I banged the shoe on the table.”

“She grew into the job. She became more, well, mayoral. . . . She listened a lot.”

While the “shoe incident” turned off some voters, it endeared her to others, who saw in her reaction a righteous passion that challenged the status quo.

A former member of the local media who covered Dixon’s career describes her appeal thusly: “She can’t help but engage. She had a lot of emotion that she would just wear on her sleeve. It’s not like she’s going to consult with her press people and she’s going to come up with the best way to respond. There was something very refreshing about that.”

Enough voters supported Dixon in 1999 to make her the first African-American woman elected as City Council president. She won re-election in 2004 and then, when Mayor Martin O’Malley left City Hall for the governor’s mansion in 2007, Dixon finished his term, becoming both the first woman and first African-American woman to hold the position.

Ironically, the same characteristics that got her to the mayor’s office—that unwillingness to take no for an answer—also got her into trouble once she was there. According to the media insider, who requested anonymity because they still cover Baltimore occasionally, Dixon’s Achilles’ heel was a sense of entitlement: “‘I’m entitled to my pay raise. I’m entitled to my driver. I’m the mayor of Baltimore.’” But, the source adds, “I don’t think she’s wrong to look back and say white guys have been having this for years. I’m going to get mine.”

At least initially, Dixon needed that armor of entitlement, says one high-ranking official from her administration. “I remember there were a lot of people who were sort of borderline upset at Mayor O’Malley for leaving the city to Sheila Dixon,” recalls the official, who sometimes works with city government and therefore also requested anonymity. “Many had a Sheila Dixon story, some interaction with her as [City Council] president that they didn’t remember as entirely positive.” But, the official maintains, “She grew into the job. She became more, well, mayoral. She was very receptive to what people had to say; she listened a lot. When people met with her, they really got the feeling that she was interested in what they had to say.”

Her devotion seemed to loosen the sclerotic bureaucracy of city government, and, as she puts it, “unclothe” the potential of Baltimore.

Says Dixon: “I was proud that our city agencies were really stepping up and being a part of the process. Because, you know, in government, people can sometimes get into their little cubicles and they do their job, but they don’t do it for a purpose. People have said to me that they felt like they had a purpose.”

Her former administration official agrees: “There genuinely was a period of excitement when people thought there was a mayor who only wanted to be mayor—nothing more—with her staff rowing in the same direction.”

That made what came next all the worse. Dixon handily won re-election in November 2007, but her days were numbered. In June 2008, the state prosecutor’s office raided her Hunting Ridge home, carting away boxes of evidence. In January 2009, the indictments came down. She was on trial by the fall and convicted on December 1. By February 4, she was out of a job, snowed in at home during the back-to-back Snowmageddon blizzards of 2010, “crying, eating snacks that I normally wouldn’t eat, watching movies, and trying to be strong for my son because he was home.”

“It was very painful,” she continues. “I mean, I loved what I was doing. The people who were part of my team, they also felt pain because they love city government. Clearly, I disappointed people. I was embarrassed. I was devastated.”

It is this shattered trust that Dixon has to mend if she has any hopes of winning back her position. But some experts say it can be done.

Jeff Smith, an assistant professor of politics and advocacy at the Milano School of International Affairs, Management, and Urban Policy at The New School in New York City, is the co-author of a forthcoming paper on political comebacks and says there are three main factors to consider: first, “the electoral context,” (i.e. “the partisan and social composition of the constituency”); second, “the nature of the past scandal and the appropriateness of [the candidate’s] response”; and lastly, the “candidate’s charisma.” Smith thinks that—in lieu of a strong challenger—Dixon has a good shot.

“The crime was not a disqualifying crime,” says Smith, whose experience with political scandal is not merely academic. A former Missouri state senator and U.S. congressional candidate, he was convicted of two felony counts of obstruction of justice in 2009 for which he served a year in federal prison. “You can’t come back from, like, pedophilia,” he continues. “Taking $500—not saying it was right or condoning it—is the kind of thing that I think voters would potentially be willing to forgive.” He further believes that “the demographics of the city are favorable for Dixon.” In fact, he sees a lot of parallels between Dixon and the late Washington, D.C. Mayor Marion Barry, who was reelected just four years after he was busted smoking crack cocaine during an undercover sting.

“I wrote a piece about Barry for Politico,” Smith says. “And the main thesis of the piece is that a lot of elites, especially white journalists, will just be appalled that voters would continue to support Marion Barry. I felt like a lot of that commentary ignored the deep history Barry had with voters, especially in the poorest sections of the city. And from what I’ve read and heard, Dixon has a similar orientation as a politician.”

“Some people are not as forgiving as others . . . and hold certain judgments.”

This would not come as news to Dixon. Before she entered the race, she commissioned an internal poll, which, according to her, revealed strong support for her candidacy overall, but some deficits, particularly in white neighborhoods. “Some people are not as forgiving as others, and some people hold certain judgments because of perceptions—and I’m not saying African-Americans don’t either, that’s not what I’m saying—but that’s where [support is weakest],” she says.

Dixon is attempting to address this by going to these resistant neighborhoods and hosting informal Q&As that she describes as “very open, frank conversations that range from A to Z.”

She also formally apologized—though with mixed results—during a May interview on WJZ, in which she said, “I think people in Baltimore want to hear my sincerity—that I am sorry for what happened. I’m apologizing about it. I also know that people want to hear that I have not taken anything for granted in that process of what happened.”

The euphemistic, passive language irked many. Writing in The Sun, columnist Dan Rodricks later called the apology “weak” and “five years too late,” and a separate Sun editorial in July snarked, “color us unimpressed.”

She does better during our conversation in September admitting that she has “a lot of regrets,” that she visited a therapist in the wake of the scandal, and that, if re-elected, she will “be more transparent in every aspect of what I do in my life.”

But it is also true that to watch Dixon discuss the scandal is to watch someone walk a tightrope between contrition and defiance. She will, in one breath, say that she was unfairly targeted by the state prosecutor and the media, and then, in the next, admit to the hurt and chaos she caused. That she seems sincere about both only complicates matters.

So it becomes not so much a question of Dixon as a question of you, the voter. Is she sorry enough for you? Did she learn enough for you? Do her positive qualities outweigh her shortcomings? Does she deserve a second chance? Dixon, of course, thinks she does.

Only time will tell if the voters of Baltimore agree.

Election 2016: The Candidates

Besides Dixon, here’s a list of those who have declared their candidacies.

Rick Black, Democrat: An accountant from Northwest Baltimore, Black’s website calls him a “fierce advocate against government overreach [who] wants to return our city to the principles of honesty, personal freedom, and financial transparency.”

Mack Clifton, Democrat: A minister and author who has experienced homelessness, Clifton says on his website that he doesn’t “believe in thinking inside the box.”

Bonnie Renee Lane, Green: A native of Michigan who has lived in Baltimore since 2001, Lane cites her top issues as affordable housing, a $15-an-hour minimum wage, and ending police brutality.

Mike Maraziti, Democrat: The owner of Fells Point bar One-Eyed Mike’s and the president of the Fells Point Main Street business association, Maraziti says his priorities include education, lowering property taxes and crime, and restoring accountability.

Connor Meek, Unaffiliated: After being mugged earlier this year, Meek wrote an editorial in The Sun calling for police stations to stay open around the clock, a policy that has since been adopted.

Collins Otonna, Independent: In an email, Otonna describes himself as a “full gospel evangelist,” who works in development commerce and runs two nonprofit foundations, building public libraries in West Africa.

Catherine E. Pugh, Democrat: Currently a state senator repping the 40th District, Pugh also has been a state delegate, City Council member, journalist, and businesswoman. She previously ran for mayor in 2011.

Carl Stokes, Democrat: Stokes currently represents the 12th District on the City Council. He previously ran for mayor in 1999.

Brian Charles Vaeth, Republican: Vaeth is a former Baltimore City firefighter who received a career-ending injury on the job and has spent the subsequent years embroiled in a lawsuit against the city.

Calvin Allen Young III, Democrat: Young, 27, is a native Baltimorean who has a degree in mechanical engineering from New York University and an MBA from Harvard Business School.

Nick Mosby, Democrat: As a Baltimore native who was elected to represent to City Council in 2011, Mosby represents the 7th District, which was consumed by much of the rioting and peaceful protesting surrounding Freddie Gray’s death.