Living On the Edge

Since 1975, Owings Mills has been promoted as the next great Baltimore suburb. Will a new round of development fulfill its promise or add to its woes?

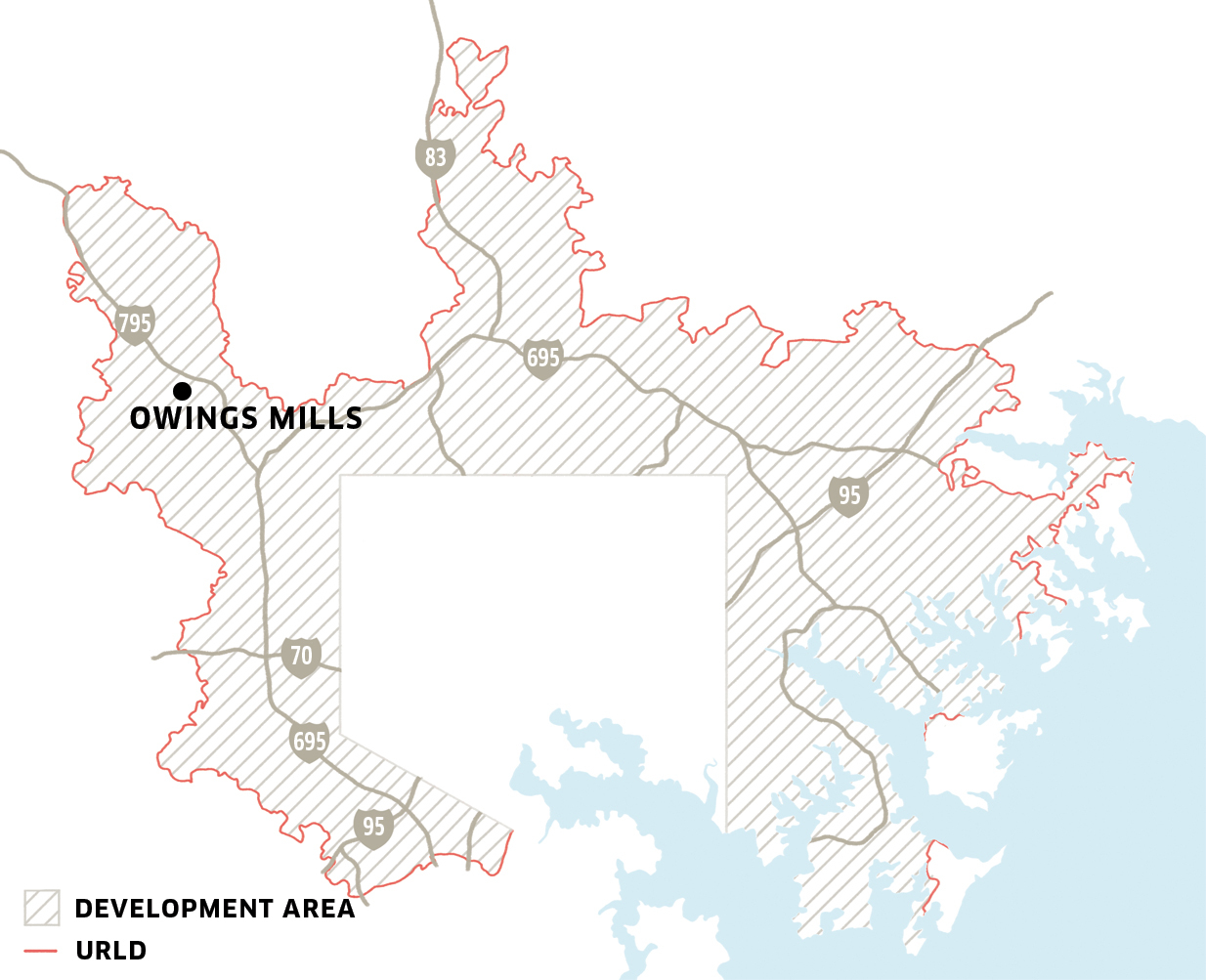

Owings Mills’ location inside the URDL, plus plans to service the town with an expressway and public transportation, made it irresistible to developers.

Quick: What do you think of when you think of Owings Mills? Do you picture the farms and mansions of the Green Spring, Caves, and Worthington valleys? Or, does your mind’s eye fill with visions of office parks and condominium complexes? Maybe you conjure a classroom at Stevenson University, which has maintained a satellite campus in town since 2004. Perhaps, if you’re a commuter, your abiding impression is of the Metro station and the whoosh of traffic on I-795. Or maybe you associate the town with football, since the Ravens have their training center and administrative headquarters there. Or you might hear “Owings Mills” and feel a Pavlovian-like urge to grab the nearest tote bag, a result of years spent watching Maryland Public Television, which has its studio in Owings Mills. Or, or, or . . .

The truth is, any of these would be a valid answer. Owings Mills is a big place. If you include every inch contained within its 21117 ZIP code, the town—technically, an unincorporated community and census designated place—covers 29 square miles from the shores of Liberty Reservoir to just west of Falls Road, and north from McDonogh Road to Timber Grove Road. It contains almost 60,000 residents, and those residents are diverse—about 50 percent white, 40 percent black, 8 percent Asian, 7 percent Hispanic or Latino, and 3 percent identifying as multiple races. And that’s not even addressing economic, religious, and educational backgrounds. So, Owings Mills has many selves; it contains multitudes. Choosing a single image for a town like that is difficult.

But forced to pick one thing—just one—many people would probably settle on the mall, which opened to great fanfare as the Owings Mills Fashion Mall on July 30, 1986, and then began a long, slow decline that culminated in its demolition earlier this year. Now, what was once 1 million square feet of marble-floored, high-end retail is just a mound of rubble on a vast expanse of parking lot—a place where a place used to be.

To the town’s detractors, the mall is a metaphor for Owings Mills itself, which was conceived in a flash of ’70s urban planning idealism but, as it grew throughout the ’80s and ’90s, came to embody the worst tendencies of American urban sprawl. Its often characterless, disconnected landscape of interchangeable office parks, strip malls, condo developments, and highways has inspired more than one observer to lament that Owings Mills is a place with “no ‘there’ there.” One resident, in an op-ed for The Sun, called Owings Mills “the urban planning equivalent of a sad trombone.”

The vacant Owings Mills Mall before demolition.

Now, after years of stagnation, another round of monumental development is promising to reshape Owings Mills. On Reisterstown Road, the former site of the Solo Cup Company manufacturing plant has been reborn as Foundry Row, a shopping center boasting a Wegmans, an LA Fitness gym, and several restaurants. The mall site is rumored for an outdoor shopping mall anchored by national retailers. And just below that, the gargantuan mixed-used development known as Metro Centre at Owings Mills is rising, having already spawned the county’s largest library, a branch of the Community College of Baltimore County, and a main drag with street-level retail and apartments above. With such change underway, it seems wise to ask: Are these projects correcting past mistakes, or repeating them?

“There’s a common theory that the things that drive development are water, sewers, and roads, and once [all] that’s in, it’s very hard to control how far out [development] goes,” former Baltimore County senior planner J. John “Jack” Dillon once said.

This being the case, the story of Owings Mills—like the story of all development, really—is closely entwined with all three.

Foundry Row features dining options like Mission BBQ and Chipotle.

Before European settlers arrived, the Susquehannock tribe used the Owings Mills area as a seasonal hunting ground, likely fishing in the Red Run, which sustained a native population of brown trout. During the 1700s, Colonists moved in, including Samuel Owings, who constructed three mills along the Gwynns Falls. These formed the backbone of the fledgling community’s economy, and gave the town its name. For the next 200 years or so, the town remained largely agrarian.

It might have stayed that way, too, but for Abel Wolman. An early graduate of The Johns Hopkins University’s engineering program, Wolman was leading the state health department in the 1920s when he realized the counties were the next development frontier.

According to a story in the November 1985 issue of Baltimore magazine, Wolman spent days sketching “a grand vision of huge subterranean waterlines running along the starburst network of roadways that stretched outward from the city center.”

Though it would take years for Wolman’s sketches to become reality, this infrastructure would dictate the county’s growth throughout the late 20th century when the four-pronged onslaught of the baby boom, the construction of I-695, a glut of GI Bill-backed mortgages, and white flight coalesced to propel development. Announcement of plans for the I-795 spur into the northwest part of the county only increased the frenzy—and panicked rural residents began to organize.

The construction of Metro Centre has netted Owings Mills the largest public library in the county and new community college learning facilities.

In 1962, The Valleys Planning Council (VPC) was established as a nonprofit conservation group with the goal of preserving as much of the county’s rolling farmland as possible. The VPC employed the Philadelphia landscape architecture firm Wallace-McHarg Associates to formulate a plan. That plan was precedent setting in that it introduced the idea of limiting public water and sewer service to certain areas of the county. This would, in turn, discourage development in rural areas, and encourage denser development in areas where services were available. Nowadays, this zoning philosophy—known as smart growth—is accepted as a more desirable and cost-effective way to accommodate development. It reduces road and infrastructure costs, decreases car dependence, centralizes services, and protects natural resources. But when Baltimore County created the Urban-Rural Demarcation Line (aka the URDL—rhymes with “girdle”) in 1967, this was cutting-edge thinking.

“One has to really keep in mind that the county’s policy of having an Urban-Rural Demarcation Line was a very progressive policy,” says Klaus Philipsen, an architect and the president of NeighborSpace, a nonprofit that works to preserve open space within the URDL.

Today, the land within the URDL, comprises about one-third of all county land, and is home to about 90 percent of the county’s population. This leaves vast expanses of the northern county mostly untouched. On the whole, this has been a good thing for the county—and the city, too. For one, it means that no resident is ever very far from open space. Second, since drinking water for much of the metro area comes from three Baltimore County reservoirs (Loch Raven, Liberty, and Prettyboy), protecting those watersheds has had far-reaching public health benefits, saving residents a whole lot of dysentery, diarrhea, and hepatitis.

Foundry Row offers 342,147 square feet of retail space and 39,000 square feet of office space.

The flip side, though, is that, for some places to be saved, others need to grow. As early as 1975, Owings Mills was marked as a growth area by county officials. It was a logical decision. It was inside the URDL, a new highway would run through it, and public transportation—the holy grail of urban planning—would service the area. But when the bulldozers appeared, some residents bristled.

“It’s a shame,” one Owings Mills resident said in front of a packed town meeting in 1985. “We lived in a nice, quiet place, and one day we hear buzz saws out the window.”

Of course, by then it was too late. But county planners and developers were aiming to make Owings Mills such a success that residents wouldn’t mind the extra commotion.

Undoubtedly, the centerpiece of that effort was the new Owings Mills Town Center. Designated for about 200 acres just west of I-795, it was to include a high-end mall, five towers of Class A office space, and a hotel. Its developer, The Rouse Company, was riding high off the success of building Columbia from scratch. It seemed a can’t-miss combination.

From the same 1985 Baltimore magazine article that mentioned Abel Wolman’s starburst waterlines comes this scene from The Rouse Company’s field headquarters: “There is always the demand for more frills, more buzzers and whistles in the course of state-of-the-art mall-making. [The] latest idea to make their Emerald City more attractive: foliage that would recall Washington’s botanical garden. . . . ‘Very European,’ says John Hennigan, the company’s Owings Mills development director, ‘like a Viennese palace garden with terracing.’”

The opulent finishes were necessary because the mall’s tenants were to be the crème de la crème of 1980s American retail—Banana Republic, Laura Ashley, Williams-Sonoma, and best of all, Saks Fifth Avenue.

On opening day, news crews descended, one even buzzing overhead in a helicopter. Gold dust and pink feathers rained from the ceiling. Champagne was poured. One estimate put attendance at 100,000.

Metro Centre is only about 20 percent complete, but will eventually have 1.2 million square feet of Class A office space, a “boutique” hotel, 300,000 square feet of retail, and 1,700 residences.

“There was so much excitement in the community when the Owings Mills Mall opened,” recalls Baltimore County Councilwoman Vicki Almond. “I fondly remember taking my daughters there for the first time, and walking the long, shiny halls.”

The residential match to the mall was Lakeside, a mini-village of 5,500 homes, on 429 acres surrounding a manmade lake that was to be created by damming the Red Run. Federal approval for that move, however, was difficult to come by.

Undeterred, work continued. Roads were straightened, widened, or added, including the optimistically named Lakeside Drive. The Metro opened in July 1987. Major employers, such as T. Rowe Price and CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield, relocated to town.

But there were whispers, too: that the mall was underperforming; that the new townhomes weren’t quite as high-end as promised; that despite—or maybe because of—all the effort expended, it felt a little soulless.

“The idea was a good one to have areas where you have concentration of growth,” says Philipsen. “But then the next step, to make these places real places, was never really pursued with any sort of diligence and planning, so what you have is . . . conglomerations of bad commercial areas.”

It all seemed to come to a head in 1992, Owings Mills’ annus horribilis.

In May, officials dropped efforts to win approval for the dam from the Army Corps of Engineers, which objected to the lake on environmental grounds. Remember that population of native brown trout the Susquehannock likely fished? Damming the Red Run would have raised water temps and killed them. So after an investment of $2 million and 10 years, the lake was dead instead.

In June, The Sun ran an editorial decrying the characterless feel of Owings Mills. This was true enough, but hardly unique. Owings Mills was an example of an emerging suburban phenomenon—the Edge City.

Journalist Joel Garreau coined the phrase in his 1991 book Edge City: Life on the New American Frontier, defining an Edge City as a place with “5 million square feet or more of leasable office space,” “600,000 square feet or more of leasable retail space,” “more jobs than bedrooms,” and, perhaps most importantly, as someplace that was a “village or farmland only 30 years before.”

Owings Mills checked all those boxes. But so, too, did hundreds of other places across the country: Tysons Corner, Virginia; King of Prussia, Pennsylvania; Scottsdale, Arizona; and pretty much all of Southern California.

Still, there was something fascinating about Owings Mills’ unfulfilled promise. The pieces were there, and yet they just didn’t fit.

“It was always an interesting example of opportunities and missed opportunities,” says Michael Stern, an urban and landscape designer who taught at the University of Virginia in the 1990s and decided to build a studio course around Owings Mills.

The vacant Owings Mills Mall before demolition.

“It had kind of the classic tensions of suburban growth. The natural environment was compelling at the same time that the built environment was not.”

As stinging as the criticism must have been for planners, the worst was yet to come.

Fairly or unfairly, by 1992, the mall had gained a reputation for crime. The problem largely stemmed from a poor connection between the mall and the Metro site, which were about a mile apart. At first, a shuttle bus ran between the two, but it was discontinued in June of 1992. But even when the shuttle was running, the easiest route from one to the other was often along a makeshift path through overflow parking lots. In late September, a 28-year-old Baltimore City resident named Christina Marie Brown was murdered on the path in a robbery-gone-wrong.

Both Philipsen and Stern view Brown’s death as a tragedy that might have been prevented by better urban planning.

According to multiple sources, The Rouse Company resisted efforts to site the mall closer to the Metro or to formalize a pedestrian connection between the two. It also allowed the suspension of shuttle bus service, though it would reinstitute it for a time after the slaying.

“At the time, Owings Mills was a high-end mall and . . . they had just these preconceived notions about folks who used transit being all poor, that then there would be more crime and more theft,” Philipsen says. “That is an argument that is made against transit every time around. This came up with the Metro, it came up with light rail, it came up with the Red Line.”

Attempts to contact former employees of The Rouse Company, which was bought out by GGP in 2004, were unsuccessful.

Though the mall would stagger on for another 24 years after the murder, it was never the same. Saks departed abruptly in 1996, and other high-end retailers followed. Even a 1998 expansion couldn’t salvage it, and the last store—a JC Penney—closed last year.

The vacant Owings Mills Mall before demolition.

Baltimore County Councilman Julian Jones, whose district includes the mall site, says the decision not to connect it and the Metro was a mistake, but that the mall’s failure can’t be pinned on just one thing. Changing consumer tastes and the rise of online retail must be factored in, as must GGP’s decision to “let Owings Mills wither on the vine” as the company faced bankruptcy during the Great Recession.

What is clear, however, is that the mall’s failure became a black hole at the center of the community, its gravitational pull warping everything else around it. It would take something big to turn the tide.

A rendering of Metro Centre at Owings Mills.

The idea for Metro Centre was formulated in the late ’90s. Looking to jumpstart redevelopment, then County Executive Dutch Ruppersberger proposed a large complex on the vast, underused Metro parking lots. After a false start with one developer, the project began to crystallize in 2002, when David S. Brown Enterprises, a third-generation development firm headquartered in Owings Mills, took over.

In its initial iteration, the development included a town green ringed by shops, offices, and 300 homes, features that were expunged somewhere along the way. But other items from the original plan—like a county library and college learning facilities—remain. In fact, you can visit them now, all glass and steel with light pouring in, students and residents streaming to and fro across a stone plaza. Opposite the plaza, the first residences—230 one- and two-bedroom apartments—are open. Underneath them, at ground level, there are shops that range from the generic (Subway) to the local (Honey House, a showcase for honey and bee-related products). When all is said and done—it’s only about 20 percent complete—Metro Centre will offer 1.2 million square feet of Class A office space, a “boutique” hotel, 300,000 square feet of retail, and 1,700 residences. As officials proudly note, its scope and design are unprecedented in county history.

“The Metro Centre is the centerpiece, because that has become the county’s first transit-oriented development. That is the most modern opportunity in planning today,” boasts Baltimore County Executive Kevin Kamenetz. “A person can live there, go to work on the Metro, go downstairs to eat at a restaurant, go across the street to the library or the community college, all without using a car.”

A mile away, along Reisterstown Road, sits Foundry Row, the second jewel in what Councilman Jones calls Owings Mills’ “Triple Crown.” Offering 342,147 square feet of retail space and 39,000 square feet of office space, Foundry Row could be dismissed as just another massive—albeit high-end—shopping center, except for this: It has a Wegmans.

On Wegmans’ opening weekend last September, there was hardly a parking space to be found, even though most of Foundry Row’s other stores had yet to open. Inside, a true cross section of Owings Mills inched through the crowded aisles.

“We’re the only county in the state to have two Wegmans, so I have a pretty good sense of this now,” muses Kamenetz. “There’s a certain panache associated with living near a Wegmans. . . . It’s the aura that it provides that allows everyone to be uplifted . . . about where they live and where they work.”

But will Metro Centre and a grocery store—even if it’s the uncannily popular Wegmans—be enough to sustain a town? Politicians and developers admit that although they’re on a roll, they need a renewed mall site for Owings Mills to truly stabilize.

“The third piece of the puzzle is the mall and, quite frankly, I don’t know who knows what’s happening at the mall,” says Councilwoman Almond, whose district contains Foundry Row but not the mall site or Metro Centre.

In late 2016, reports circulated that Kimco Realty, North America’s largest publicly traded owner and operator of open-air shopping centers, was planning to redevelop the site as an outdoor mall anchored by a Walmart and similar big-box stores. This was not welcomed news.

“I would like them to jump a little higher than that,” stated Kamenetz in early February. “I think they can do better.”

Perhaps heeding the public outcry, in February, Kimco sent out surveys to some Owings Mills residents, asking for their input on the site’s future. There is no public timeline for a decision, and Kimco representatives did not return phone calls for comment.

The crown jewel of Foundry Row is the Wegmans, which opened to much fanfare last September.

Philipsen, the president of NeighborSpace, lives in Catonsville, so he did not receive a survey from Kimco. But if he had, he knows what he’d recommend. He believes that, despite their proximity, Metro Centre, Foundry Row, and the mall site are still not connected in any meaningful way.

“A real public park in the heart of Owings Mills could be an attraction that can fuse things together that are otherwise too far apart,” he says.

Though stranger things have happened, a for-profit developer ceding buildable land to a municipality for recreational space seems unlikely. But that, says Philipsen, is when the county needs to step in and exercise the foresight it showed in the 1960s and ’70s.

“If they just let every player do whatever they want it will never add up to be the right thing,” he laments.

Or maybe it will. Maybe what Owings Mills needs most of all, is time.

“Edge City’s problem is history,” wrote Garreau. “It has none. If Edge City were a forest, then at maturity it might turn out to be quite splendid, in triple canopy. But who is to know if we are seeing [only] the first scraggly growth?”

One resident, at least, seems encouraged. Elizabeth Bastos moved to Owings Mills from Cambridge, Massachusetts, seven years ago. Initially horrified and alienated by Owings Mills’ barren civic landscape (she’s the one who likened it to a sad trombone), she now finds herself guardedly optimistic about its prospects.

The new Metro Centre IS anchored by branches of CCBC and the Baltimore County Public Library.

Last September, in an op-ed provocatively titled “The Paris of Baltimore County,” she applauded the town’s progress.

“With the new Metro Centre anchored by CCBC and the Baltimore County Public Library, there is a freshness,” she wrote. “A there-ness. There is beginning to be bustle. . . . And I’ll be there on the plaza, people-watching, eating my lunch, helping to make it the Paris of Baltimore County.”

Don’t laugh. Paris, like Rome and Owings Mills, wasn’t built in a day, either.