News & Community

Susan's Choice

Onetime golden boy Jim Harrison is having a very bad year. Is it because he doesn't know where his wife, Susan, is? Or is it because he does know?

Jim Harrison misses his wife. In his paper-strewn family room, the retired McCormick spice company bigwig widens his eyes until their cloudy blue irises swim in whites, like two eggs frying.

“I pray to God Susan comes back, but the odds of her coming back are not good,” says Harrison of his estranged wife, who vanished from his house on Friday, August 5, 1994. “It’s possible she went to Ireland.”

His face is all pathos and distance, a trans-Atlantic wrong number. Besides some of his relatives, Jim is the only person close to Susan Harrison who doesn’t say she’s dead, who doesn’t beg to learn how she was killed, who doesn’t volunteer haunting images of delicate Susan in a landfill, Susan down a well.

If you mention the common suspicion that Jim knows more about Susan’s disappearance than he’s willing to admit, you won’t cast a shadow on his broad, ruddy face. “The vast majority feel I have nothing to do with it, and they’re right,” says Harrison, curling back his lips to reveal his small, rectangular teeth. “Thousands of people have been very supportive.”

That Harrison will not name one person out of these thousands does not mean he knows where his wife is. It only means he stands alone, aloner by the day.

Monday, August 8, 1994, 4 p.m.

(Three days after Susan’s disappearance. Matt Gordon, the son of Susan’s dear friend Mary Jo Gordon, is trimming bushes at his mother’s Greenspring Valley house. Susan often stayed there after fights with Jim. Jim Harrison pulls up in a long, dark-blue sedan and sticks his head out the window.)

JIM: Is your mother at home?

MATT: No.

(Jim parks and gets out of the car. Matt notes that Jim’s face is puffy and flushed; his hands and speech seem unsteady. Matt smells alcohol on his breath.)

JIM: Do you know where I might be able to find your mother?

MATT: She’s at work.

JIM: Susan is missing.

MATT: I know. I heard.

JIM: I’m very worried. I have absolutely no idea where she might be. I thought your mother might know. Could you give me her phone numbers at home and at work?

MATT: Sure. Wait here. (Jogs inside for paper; writes down phone numbers; returns and hands them to Jim.)

JIM: Thank you. If you hear an thing, please, please let me know.

(They shake hands. Jim walks back to his car.)

What’s widely known: More than a a year ago, bright generous Ruxton mom Susan Hurley Harrison vanished. She was last seen by second husband Jim, from whom she was separated. He said Susan had been to his house several times that day, acting in turns loving and abusive—”going manic-depressive,” he called it. To Cockeysville police, this was a familiar description. It was how Jim usually explained the fights that had made the Harrisons’ home a frequent destination for their blue-and-white squad cars.

Susan had probably driven off a about 10 p.m., Jim said-he wasn’t sure, because he’d gone to bed to avoid her vitriol. Her green Saab convertible was found parked at National Airport with the key in the ignition and new gas in the tank. But no one has heard from Susan, and no body has turned up. Police searched Jim’s house, which was cleaned around the time Susan disappeared by a new maid who quit almost immediately. Bur if police found evidence of foul play. they’re not talking. Jim took a lie-detector test. Police told him he failed, but he’s sticking to his story.

Jim has cooperated with investigators and reporters. against his lawyers’ advice. But unlike Susan’s siblings who hired a private investigator and who call pol1Ce several times a week for progress reports, Jim Harrison has hired no one to look for Susan. And in the 15 months since her disappearance, he has called poke just a handful of times.

“I feel Jim holds the key to the mystery,” says Lieutenant Sam Bowerman, a specialist in criminal personality profiling. “He says it’s ridiculous for anyone to think anyone would have harmed Susan, because he loved her. But love really doesn’t have anything to do with it.”

September 1994

(About one month after Susan’s disappearance. In Jim’s family room. William Ramsey, the lead detective investigating the case, is questioning Jim.)

RAMSEY: So, Susan is down at the bottom of the stairs, screaming at you, and you just got to bed and fall asleep?

JIM: Yes, that’s right.

RAMSEY: And when you do wake up again?

JIM: About eight.

RAMSEY: Not four a.m.?

JIM: Four?

RAMSEY: A C&P lineman heard a car door slam on your property about then, heard a car start and drive off down Timonium Road, away from I-83.

JIM: How did they hear that?

RAMSEY: The lineman was up on a utility pole.

JIM: Must have been someone turning around in my driveway. People turn around there all the time.

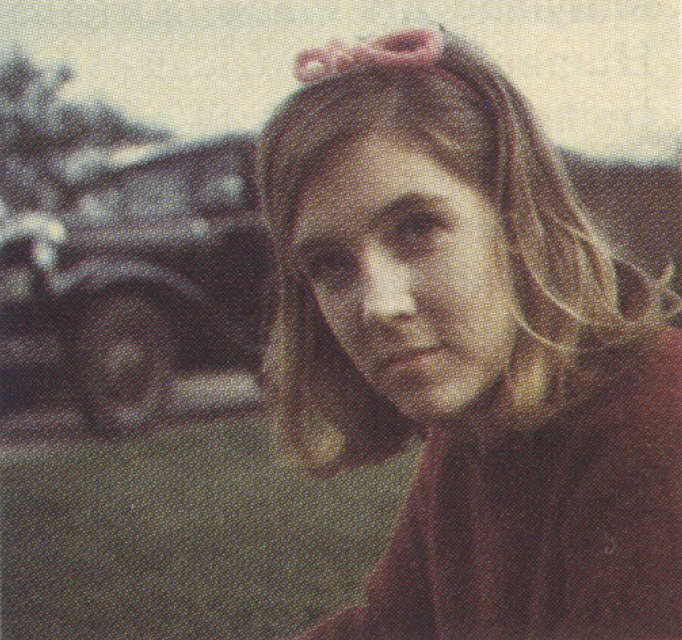

Susan Hurley Harrison was talkative, a fragile blonde with an easy, contagious laugh. If a friend were blue, Susan would conjure a ridiculous image—a nun driving a beer truck, say—and present it for comic effect. “Now laugh!” she’d command, with just a vestige of a Boston accent. And she would laugh herself.

One of five children of a Massachusetts silver-company executive, Susan also had a creative, domestic bent. “There were always projects she was working on,” recalls brother John Hurley, eight years her junior. “When I was little, she’d let me help her lay out these big tissue-paper things she’d use to make patterns for clothes. Or she’d hold my hands up while she rolled up a ball of yarn off them.”

Susan studied art history at Manhattanville College, then found curatorial work in Boston. At 25, she married law student Tom Owsley, a Harvard chum of her older brother Bill. Joining Tom in North Carolina, Susan worked two more years, until Tom graduated and the couple moved. A year later, in 1970, her first son, Jonathan, was born.

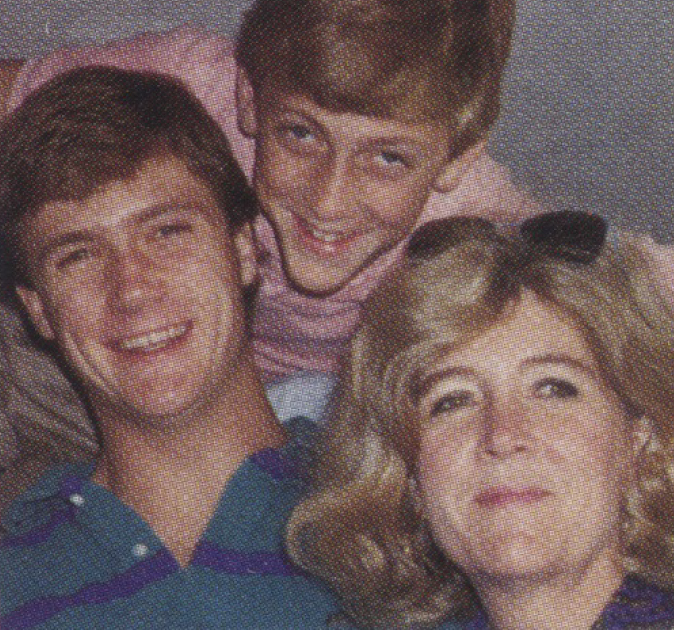

Jon and his younger brother, Nick Owsley, entered Susan’s world at its center and stayed there. “Those kids were her life,” says Clara Arana, a friend and feliow craftswoman. “They were what kept her alive.”

As youngsters, Jon and Nick learned to expect their doting mother at every school event, every lacrosse game. Jon had to beg her to stay on the sidelines: “No matter what, never, ever run down onto the field if you think I’m hurt, I don’t care how bad it looks,” he said. “It’s not cool for a guy to have his mother run down on the field in front of everybody.”

She overwhelmed the boys with handmade gifts. “She’d make us sweaters, mittens, lamp shades, everything,” recalls Nick, now a junior at Middlebury College. “Sometimes you’d just mention something offhand, just admire it, and she’d make you one. You had to be careful what you said,” he jokes.

Susan told her boys they were her best friends, that they understood her like no one else did. The boys say she offered a steady stream of solid guidance; even in college, she was the first person they turned to for comfort. At a memorial service in June, Jon read a remembrance of Susan, written as a letter to her. Here is part: “When our teammate died my junior year, I picked you up at the airport just hours after I found out. I was completely distraught, suffering in a way I could not comprehend. ‘Oh, Jonathan,’ you said, ‘I’m so sorry.’ And you held my hand the whole way down from Burlington to Middlebury.

“And true to form, always thinking of others, you told me to make sure that his mother had a Mother’s Day card—it was only three days away—signed by the entire team, so that she would know she was not alone.”

November 22, 1994

(Almost four months after Susan’s disappearance. In a Towson courtroom, at a hearing to name Jon the guardian of Susan’s belongings. Her husband is legally the first in line for that task, but the family wants Jon to be named instead. Jim does not challenge the request, but he has nevertheless been asked to testify. Carey Deeley, the attorney for Susan’s four siblings, first husband and sons, is questioning Jim.)

DEELEY: Your wife, on July 27, 1993, checked in at the hospital to be treated for a bruise on her right forehead, down into her eye, with swelling noted to the doctor in the hospital. Her knees were scraped and sore. Her wrist had been twisted. Her right eye was almost swollen shut.

DANA WILLIAMS (JIM’S LAWYER): Objection.

DEELEY: Does that ring a bell?

WILLIAMS: Objection.

JUDGE CHRISTIAN KAHL: Overruled.

JIM HARRISON: I don’t remember that situation. DEELEY: Showing you what’s been marked for identification—

WILLIAMS: Can I see that, Mr. Deeley?

DEELEY: —as—

JIM: Black eyes? Is that what you’re going to show me?

DEELEY: Let’s see what I’m going to show, sir. (Shows two photographs of Susan with a blackened eye.) That’s your wife?

JIM: That’s Susan.

DEELEY: And those are fair and accurate representations, are they not, of what she looked like after the July, 1993 incident. Right, sir?

WILLIAMS: Objection, your honor.

JUDGE KAHL: Overruled.

HARRISON: Oh, her eye was much blacker than that. In fact, both eyes were blacker.

DEELEY: And how did her eyes come to be black like that, sir?

WILLIAMS: Objection.

DEELEY: What did you do to her on that occasion, Mr. Harrison?

WILLIAMS: Your honor, that’s two questions.

JUDGE KAHL: One at a time.

DEELEY: What happened, Mr. Harrison, in July of 1993?

WILLIAMS: Objection.

JUDGE KAHL: Overruled.

HARRISON: We had come back from the beach, from Ocean City, and she had been manic depressive on the way down, and then recovered. And when she got back to 610 West Timonium Road where we live, she went berserk again. And she ran around the house. She was smashing stuff around the house. She was yelling. She was screaming. And she was running so fast and had been drinking again.

And she ran out the door of the new sunroom that we have, and she fell on the steps as she went out. Because I saw her stagger and fall as she rushed out the door. And she banged her head, as I recall, I guess it was right here {points), really banged it. And it resulted in an artery or a vein or whatever, pouring blood, so that this particular eye, her right eye, really got black, and the left eye became sort of lightly black.

DEELEY: Do you deny, sir, the report of the emergency room of July 27, saying that you hit her in the head with your fist at that time?

HARRISON: That is an absolute lie.

James Joshua Harrison Jr. was born in 1936 at Johns Hopkins Hospital. His father, who grew up in rural Virginia, was working as a chemical engineer, and the family lived on St. Paul Street. When Jim was five, his parents bought a house on Morningside Drive in Towson and moved there with Jim and his sister, Ann.

Jim’s parents sent the boy to the Gilman School where he excelled. In his senior year, the football coach nominated the 145-pound end to be Baltimore’s unsung sports hero of the year, an honor bestowed by McCormick & Co. Jim’s connection to the school endures—in the year before Susan disappeared, he co-chaired his class’s 40th-anniversary fundraising drive, the most successful reunion drive in the school’s history.

Jim studied engineering at Cornell, taking a semester off when his grades began to suffer from too much partying. While on hiatus, he met a high-spirited Goucher student named Molly Darden. He returned to Ithaca, and a year later Molly joined him as his bride. By the time Jim graduated in 1960, their third child was on her way.

After a stint at Whiting-Turner and six years at Martin Marietta—during which earned a law degree from the University Baltimore—Jim got a job as assistant counsel at McCormick. There, he rose to general counsel, then chief financial officer treading one proven path to the president’s office. Along the way, Jim earned an M.B.A. from Loyola College, finishing first in his class.

Jim stood particularly tall at McCormick in 1980when he learned that one division had been cooking books to swell its bottom line. It was he who urged corporate brass to come clean, launch an outside investigation and re-issue profit figures for several years past. He also distinguished himself during an unwelcome takeover bid by a Swiss company in the early 1980s, and by his sale of McCormick’s vast real estate holdings to the Rouse Company in 1988.

Jim was known as a brilliant businessman. But some say he could play the fool when it served him. When plotting an acquisition, says one observer, “he’d play this ‘Oh, I’m just a poor old country boy’ shtick. The next thing you know, McCormick owns the company and he’s rocking in his chair like Grandpa.”

March 31, 1995

(Almost eight months after Susan’s disappearance. Cocktails before a dinner to open the golf season at the Green Spring Valley Hunt Club. In the member lounge, Susan’s first husband, Tom Owsley, stands in a group near the bar by the door. Enter Jim Harrison, also a member. Tom notes that Jim is red-faced and unsteady; then Tom turns his back.)

JIM: Oh, Tom, how are the boys?

(Tom says nothing.)

JIM: Jonathan has Susan’s car?

TOM: Yeah.

JIM: If there’s anything I can do, just let me know.

TOM: All we need is to find Susan’s body.

JIM: Oh, I pray to Jesus that’s not what happened.

(Tom walks away.)

When Jim met Susan in 1976, both were married. Susan had her two sons with Tom. Jim had six children with Molly, plus a five-bedroom house in Lutherville and the inside track to the helm of an international corporation.

In the following years, the couples socialized at conferences of corporate executives (Owsley is a vice a president at Crown Petroleum), and then the Owsleys moved from Reston, Virginia, to the Greenspring Valley in 1982, the Harrisons were ready to welcome them to Baltimore.

By then, Susan’s school-aged sons didn’t need her constant attention, and the domestic applications of her art training—needle-point seat covers for the dining set, hand-painted lampshades for herself and friends, a home-sewn down jacket for Tom—stopped seeing like the makings of an adult’s whole life. In the same position, some of Susan’s contemporaries struck out on their own; others stayed married but started careers. Susan just for restless.

In stepped good-time Jim, admiring Susan’s face and heart, playing to what many say was a lifelong lack of self-confidence. “He showered her with attention,” recalls Tom Owsley. “He knew how to put on the big push.” They started an affair in June of 1983.

The fall of 1984, the two couples saw a play together. Sitting around the Owsleys’ dining room table afterwards, Jim and Susan revealed their relationship to Molly and Tom. “All hell broke loose,” recalls Molly Harrison. That October, Jim and Susan left their families and moved in together.

The first person who called 911 about Susan and Jim’s troubles was probably Tom. He recalls trying to help Susan during early strife, and once again even drove her to the police station. In October of 1986, Susan called Tom at work, despondent, saying she had take a lot of pills. Paramedics arrived at the Lutherville house she shared with Jim, but Susan was gone. Jim told paramedics they’d had a fight and said she might be at Tom’s house. An ambulance found her there, but she refused treatment, so they called Jim to come get her.

In December, 1988, Jim and Susan married. By that time, she already had suffered a broken arm—she said at the time she’d fallen off a bike, but years later told her family that Jim had broken it. She had also called police numerous times, claiming Jim punched her in the eye, Jim punched her in the mouth, Jim threw water on her, Jim raped her. He routinely denied the charges; she usually dropped them. Shortly before their wedding, Jim was acquitted of two counts of battery against Susan. After their wedding, this pattern of injuries and calls for help continued.

In October, 1989, as part of a McCormick sponsorship, Jim and Susan played host to two teenage girls from the perky traveling stage show “Up With People.” Susan left the company’s welcome-to-Baltimore dinner early. When Jim and the girls arrived home later, Susan immediately began berating him, accusing him of sleeping with both of the girls—at least, that’s what one of the girls told police she had said. The visitors’ luggage was emptied and their clothes strewn about the house. For some time afterwards, Susan was unwelcome at McCormick company functions.

“She was horrible,” says Molly Harrison. “She misbehaved constantly. Her family is completely blind to it.”

According to Molly, Susan’s portrayal in the local press has been misleadingly gentle. “We’ve been calling her ‘Saint Susan’ since the Towson Times story came out [in May, 1995],” she says. “It’s the joke of the city.” Molly says she has seen Susan “go off manic” many times, running off into a thunderstorm once after Jim.

Molly also says that after Susan and Jim fought, Susan would call Molly and her children each “30 times,” looking for him. Sometimes she’d ask for Jim, sometimes she’d just pause and hang up. Molly says phone company records prove the hang-ups came from Susan. (Jim says he does not remember Susan ever using the phone in this way.)

“She stalked us,” Molly says. “Every time the Owsleys say they wish Jim had never met Susan, I say it five times. Frankly, I don’t wish anybody dead, but I hope I never see her again.”

Wednesday, July 12, 1995, 1:30 p.m.

(Almost a year after Susan’s disappearance. Owings Mills District Court. Jim has been charged with drunk and disorderly conduct in Garrison. Later today, Jim will request and receive a postponement. Jim, his lawyer, and his two grown daughters, Betsy and Wendy, are waiting among the blond wood pews in Courtroom No. 1. There to watch the proceedings: Carey Deeley, the lawyer for Susan’s siblings and sons; detective William Ram-sey; lieutenant Sam Bowerman; a reporter.)

BETSY: Dad, I had a dream that Susan was found alive and well in Missouri—

JIM: Missouri?

WENDY: —and that her boyfriend’s left her and she can’t decide whether to come back. (Laughs.)

JIM: (His eyes widen.) I pray to God you’re right. Uh, that God is talking to you in your dream.

In late 1991, Jim learned he had been passed over for the job of McCormick CEO. Ironically, Harrison was beaten out for president by a man who had joined McCormick as head of a California spice company that Harrison had been instrumental in acquiring. Says Harrison in the third person, an idiosyncracy: “A lot of people, including Jim, figured that Jim was going to be the successor to the McCormick [company]. But Bailey [Thomas] and Gene Blattman became very close friends. And Gene Blattman, who was a fine guy, beat me out.”

After news of the promotion broke, Harrison took “early retirement” and stopped going to work, two years before his pension kicked in.

Jim began spending days at home, and the couple calls to the police became more frequent. Often, both had been drinking. Each claimed the other was the attacker, though Susan is the only one whose bones were ever broken. (Jim once showed police a yellowing bruise, saying Susan had just caused it. But Susan said a doctor had caused it days before, and the doctor confirmed this.) Susan began telling friends and family about these confrontations, but would later soften her words. Had Jim yelled at her? She’d provoked him. Had he shoved her? She’d exaggerated the injury. Besides, he had been ever so sweet to her since.

“When she would first call me, she would be extremely distressed and disoriented,” recalls sister Molly Moran, who lives in Georgia. “Then later, she got defensive, blamed it on herself, glossed over the whole thing. I didn’t know what to believe.”

Susan saw several counselors during her marriage to Jim. One Boston doctor—a cardiologist, the family points out—diagnosed manic-depressive illness, and a local doctor prescribed lithium for it. But her family says the psychiatrist Susan was seeing when she disappeared had rejected this diagnosis. Susan was anxious and confused and filled with rage against Jim, they claim, but she was not bipolar. The psychiatrist they name declines to comment, however, citing confidentiality rules.

Jim and Susan each claimed the other had problems with alcohol, and they went to Alcoholics Anonymous together for a time in the early 1990s. Susan’s family says Susan did not have an alcohol problem, but that Jim does. Jim denies he has an alcohol problem, but says Susan did. For Christmas. 1987, one of Jim’s relatives gave him an Alcoholics Anonymous manual. The inscription had nothing to do with Susan.

The summer before she disappeared—the summer of the black eye—Susan got a 10-day court order to keep Jim away from the house. She asked a judge to extend the order to 180 days, but the judge refused to do so, because Susan had accepted a ride from Jim while the order was in force. If Susan went willingly with Jim, the judge ruled, the government could not keep him away. The order lapsed, and Jim came home. To celebrate their reconciliation, the couple bought a $47,000 racehorse. Susan picked her out, so they named her “Susan’s Choice,” a strangely melancholy echo of a book Susan loved—Sophie’s Choice—about the choice between two children’s lives. The main character, bone, Sophie, lives and dies with Nathan, a charmer with an irrational, abusive temper. The most memorable line from the movie is hers: “The truth? I don’t even know what is the truth, after all these lies I have told.” In spring of 1995, Susan’s Choice broke her back in a Florida stable and was put to death.)

Why did Susan stay with Jim? For one thing, she was used to living well—she flew Jon to college in the McCormick jet; she had a closetful of evening gowns. In her divorce over from Tom, she had foregone alimony, and it had been many years since she had worked. And there was Jim, a $4-million man, ready to take care of her. When they weren’t fighting, he was extremely attentive. On the 27th of every month for years—in memory of the date when they started their affair—Jim sent Susan a gooey card.

Besides, after his retirement, Susan felt sorry for Jim. Calling from home to the friend who had sheltered her after one blowup, Susan explained her return: “This morning, he got up, put on a tie, he put on a jacket. And where did he go? To the post office.”

Monday, July 17, 1995, 9:15 a.m.

The picture-window lobby of the Ocean City District Court. Jim has been charged with drunk and disorderly conduct in a hotel parking lot. His lawyer has just arranged for the trial to be rescheduled at the circuit court in Snow Hill, so Jim can have a jury. The attorney and Jim’s daughter Betsy, also a lawyer, are conferring earl by the entrance. Lawyer Carey Deeley and a reporter are sitting outside the courtroom, on a long wooden bench. Jim walks over to Deeley, the man who had questioned him for two hours at November’s guardianship hearing.

JIM: (Kindly, pulling a small notebook from his jacket pocket. What’s your name?

DEELEY: Carey Deeley.

JIM: (Writes this down.) And who do you represent?

DEELEY: I’m with Venable, Baetjer and Howard.

JIM: (Writes this down.) You were at the other one, weren’t you?

DEELEY: Mr. Harrison, I really can’t speak to you.

JIM’S ATTORNEY: Jim, come here, please.

JIM: (To the reporter, brightly.) How are you?

THE REPORTER: Just fine. What’s up?

BETSY: Come on, Dad.

(Detective William Ramsey rounds a corner from the district attorney’s office.)

RAMSEY: Hi, Jim.

JIM’S ATTORNEY: Jim, why are you hanging around with those people? Those people are not on your side.

In the fall of 1993, Nick left for college, and Susan consulted a divorce lawyer. She also began planning a business to produce the hand-painted lamp shades she’d been making for friends for years.

The Harrisons’ calls to the police that fall include accusations that each had attacked the other; had destroyed things in the house; had stolen belongings; had trapped the other by parking behind them in the driveway.

Finally, on December 29, Susan called police from Mary Jo Gordon’s house. She had planned to meet Gordon for dinner the previous evening, but told police that Jim had held her captive in their house most of the night. She said he had punched her and shoved her into the Christmas tree. Each said the other had tried to run them down in the car, and police found tire tracks on the lawn. This was it, Susan told friends. She rented a carriage house in Ruxton and took everything from the house she could take, including the washer, the dryer, both stereos and all the drapes.

Susan served Jim with a request for support, enumerating the injuries she’d received during their relationship. She blamed Jim for them; Jim denied responsibility.

But before long, Susan and Jim were dating again. “Theirs was a really destructive relationship, but addictive, you know?” Gordon says. “It was just a matter of time before they would make contact, and then the whole thing would start all over again.” Shortly after Susan moved out, Jim helped her negotiate a lease for studio space at the Mill Centre in Hampden, next to Clara Arana’s art-jewelry studio.

Jim says that when Susan disappeared, she was on the verge of moving back into his house. He points to his dining room curtains, which Susan had re-hung, as proof. But a Realtor the couple consulted after their separation says it was he who suggested re-hanging the drapes, to make the house more marketable. Her family says she returned them reluctantly, so the house would sell and she could get her halfshare of its value. And she could get away from Jim.

But no one disputes that a week before she vanished—July 25 to 27—Susan and Jim took a holiday together in Ocean City.

“It was like she was in two worlds,” says one good friend. “She wanted to be her own person, but even when they were separated, she was still wearing her big diamond ring.”

Sunday, July 30, 1995, 7:30 p.m.

Dinner in the enclosed porch at the Turf Inn in Timonium. Along one wall of the narrow room, windows display cars streaming down York Road. On the opposite wall hang china masks of movie stars: Bogie, Joan Crawford, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe. Jim Harrison is having dinner with a reporter.)

THE REPORTER: Have you ever known anyone else who was manic-depressive?

JIM: There was somebody at Cornell, but I don’t remember who.

THE REPORTER: So, apart from Susan, you’ve never known anyone who had manic-depressive illness, never seen the symptoms?

JIM: No.

THE REPORTER: Do you realize that the symptoms you describe as Susan’s “going manic-depressive” aren’t generally considered symptoms of manic-depressive illness?

JIM: Not symptoms? (Pauses.) It was embarrassing.

THE REPORTER: How so?

JIM: She would call the police, the police would come, and nothing happened.

THE REPORTER: Nothing happened, but she would have a broken arm, broken ribs, black eyes—

JIM: The black-eye thing was ridiculous. She fell and bumped her head. It had nothing to do with me. She’d gone berserk, started running around. Then she fell.

THE REPORTER: Did you ever think something besides manic-depressive illness made her do these things?

JIM: No.

THE REPORTER: According to psychiatrists—

JIM: Psychiatrists?

THE REPORTER: I called a few experts, and they said that manic-depressive illness involves moods that come and stay a while; you take it in and out of the room with you. Most said that what you describe—this sudden, very limited rage, directed at one person isn’t classically a symptom of manic-depressive illness, let alone the only symptom. It could be borderline personality, maybe, or just someone who feels violated.

JIM: (Pauses. Picks at his cuticle.) When she wasn’t manic-depressive, she was great.

On Sunday, July 31, 1994, Susan called police. She said Jim had come to her house at 12:30 in the morning and asked her to dinner. When she declined, she said, he twisted her fingers until he injured them. She told police she would press charges.

Jim also called police that day, to complain that while he was out playing golf, someone had let herself into the house and cut up his summer clothes with scissors. He suspected Susan—and in fact, an embarrassed Susan confessed to a relative that out of anger, she had done this. Jim also said he was missing a wallet containing $4,000 in cash—a wallet that he now says is still missing.

During a phone call that evening, son Nick gave Susan a familiar ultimatum: Choose Jim or choose your sons. We want no part of him. Characteristically, Susan waffled, Nick says. It’s not as easy as that, she told him. There are financial considerations.

On Monday, August 1, Nick says, Susan called back. “I’ve made my decision,” Susan told him. “I want to be with you and Jon.” The two talked eagerly about their plans to visit her brothers in Boston that weekend.

On Wednesday, August 3, Susan called Clara Arana. “I want to take you to lunch Monday, when I get back from Boston,” she said. “I have something to tell you.” Replied Arana: “I hope it’s the news I’ve been waiting for”—that Susan’s vacillation had ended. “You’re going to like it,” Susan replied. “But I want to tell you in person.”

On Thursday, August 4, Jim changed the lock on his family-room door, to keep Susan out of the house she co-owned.

On Friday, August 5, Nick and Susan decided not to drive to Boston that day, as planned. Instead, they would take an early plane on Saturday. Nick spent part of the day with Susan in Ruxton, then went to pack a bag at his father’s house and pick up Chinese takeout. Susan gave him her ATM card to get cash for the trip; she had only $5 and almost no gas. She also offered Nick her Saab to drive-if he had accepted, she would have been stuck at home, because she didn’t drive his stick-shift car-and told him she would nap until his return.

At 5 p.m., Susan called her brother John in Boston. She sounded worried, but he was running out the door, so he promised to call her back at 7:30. When he called back a half-hour early, Susan didn’t answer.

When Nick arrived back in Ruxton, Susan was gone. The door was ajar, and she had taken only her wallet and the spare car key.

Jim’s older daughter Wendy saw Susan arrive at her father’s house a little before 7 p.m. Then Wendy left. And Susan went inside.

(At the Turf Inn)

JIM: We fell in love. We couldn’t stop it. It just couldn’t stop. Thank God. Because I love her so much, and she loved me so much.

THE REPORTER: A lot of people say she was addicted to you.

JIM: It’s really neat. Life is full of so many different people. But then you meet somebody who is the person above all. We couldn’t stop it, so I had to leave my wife and six children. She left her husband and two children.

THE REPORTER: What do you make of people saying she was addicted to you?

JIM: That’s called “in love.” If you’re really deeply in love with someone, that’s addiction.

The year since Susan’s disappearance has not been a good one for Jim.

In December, his second son, Bill, fired a shotgun in his Florida apartment complex, drawing a SWAT team.

In January, his first wife, Molly, sued him for failing to make an alimony payment. She told the judge Jim cut her off because she wouldn’t let him celebrate Christmas at the house she owns with a ‘ companion. (Jim denies making this threat.} Jim paid about half of the alimony right before he received Molly’s lawsuit. When a judge ordered him to pay the rest of it, he paid.

In February, son Bill turned up in the Appalachian mountains with frostbite. Jim brought him to the hand clinic at Union Memorial Hospital, where parts of his fingers were amputated.

In March, after talking to Tom Owsley at a golfers’ reception, Jim had words with someone else at the club and was asked by the management to leave. According to a police report, he stumbled across a nearby road and got in a tangle with an officer trying to help. At the Garrison precinct, Harrison shoved an officer and “continued to sing loudly ‘F-k you’ over 45 times in succession.” His trial on these charges has been rescheduled for October 2.

In May, son Bill and a stranger died of gunshot wounds on a bus in Florida. Police say Bill fired the shots. Jim isn’t sure. “There were six people on the bus,” he says. “I wonder if something else happened. Like, they killed him and the other guy.”

In June, at an American Bar Association meeting in Ocean City, Jim’s car bumped into a parked truck on a hotel lot, and he was arrested for driving while intoxicated. The arresting officer said Jim slapped him and offered him a bribe. His jury trial has been scheduled for November 8.

(At the Turf Inn)

JIM: It’s much ado about nothing. I was patting him on the shoulder, trying to make friends.

THE REPORTER: He said you slapped him on the wrist.

JIM: I never did.

THE REPORTER: He said you offered him money to let it drop.

JIM: In Ocean City?

THE REPORTER: Yeah.

JIM: No.

THE REPORTER: Does that mean you did offer the Garrison cop money?

JIM: No, neither. I just don’t think you should be involved in that. You’re making me look like a horrible criminal. And I’m not.

Jim Harrison is forever offering people things. Admire the electric Santa by his hearth—he bought one for each of his twin granddaughters last Christmas, but the parents were content with just one and he’ll quickly ask “Want it?” He really hates being treated to dinner. “Please let me buy,” he begs endlessly.

Some, including Jim, say he’s just a generous guy who gets pleasure out of helping people. “I just love people and I love to help people, whether it’s children or whatever,” Jim says. Others, including Susan’s family, say Jim wants people to owe him. “He’s much more willing to buy someone’s friendship than be someone’s friend,” Jon Owsley charges.

When it came to Susan, Jim was generous to a fault, ladling gold jewelry onto her the way she pressed homemade sweaters on her boys. In return, Jim expected single-minded devotion. Jon Owsley says that once, during a conversation in Jim and Susan’s sunroom, Jim told him that men and women could not be platonic friends. Any man who befriended his wife had more than friendship in mind. (Jim denies ever saying this.)

Susan once told a friend about a tiff at a baseball game. While Jim went to fetch her a snack, Susan began chatting with a couple nearby. When Jim returned, he chastened her for speaking to another man. (Jim says this never happened.) Sometimes, Jim punished Susan by leaving her stranded, says a friend who periodically retrieved her from a restaurant or her country club. (This, Jim does not deny.)

(In Jim’s family room)

THE REPORTER: You’ve got a lot of people hallucinating around you, Mr. Harrison.

JIM: What do you mean?

THE REPORTER: Well, sometimes I’ve got three or four people saying something happened one way—that you said a particular thing—and you tell me you never said it.

JIM: I can’t help it if people lie.

Whether Susan is dead or alive—and whether or not Jim was involved in her disappearance—she’s clearly stranded again. And what troubles her family most is not being able to bury her. “Where is she?” wonders Tom Owsley, rolling up his brown linen napkin after dinner at home. “In a landfill? An abandoned well? Just covered over with branches?” He clicks his tongue and turns away.

“She is just someone who shouldn’t ever be in the situation she’s in right now,” says son Nick. “She should be up in Massachusetts, next to her mom and dad. Not for my sake—I’ve done enough grieving. But for her sake. Right now, there’s no stone, no way for her to be remembered.”

Police investigators say she has almost certainly been murdered by someone close to her. No random stranger need go to the trouble of hiding her body, they reason.

If that’s the case, then someone close to her knows where she lies. Someone can visit her grave. And that someone is the only person to whom Susan now belongs.

(At the Turf Inn)

THE REPORTER: Nick says that he saw you attack his mother. That one night when he was 12, he was staying at your house. Jon and Tom—

JIM: Who?

THE REPORTER: Jon and Tom Owsley were out of town. And Nick heard you arguing with Susan, so he called Jon, and Jon called his girlfriend to come by the house and get Nick.

Nick was down at the bottom of the driveway, waiting for Julie, and he saw his mother run out of the house carrying a bunch of her lamp shades, one torn and the rest unharmed. She ran to the trunk of her car with them, and you ran behind her. Before she could get the key in the trunk, you grabbed her and started shaking her violently.

When Nick yelled at you to stop it, you just stopped short, gave him a little smile, and walked back into the house. Do you remember this?

JIM: No. It didn’t happen.

THE REPORTER: Why would he say that it did?

JIM: She turned the boys against me.

THE REPORTER: Enough for him to remember things that didn’t happen?

JIM: He’d been brainwashed.

THE REPORTER: Why would she want to turn the boys against you?

JIM: When she went manic-depressive, I she’d say bad things, she’d call the police. As far as the boys are concerned, she didn’t want to be a liar. So she let them believe things.

Like his brother Nick, Cornell law student Jon Owsley is a self-possessed, good-looking Gilman School grad. Jon’s girlfriend, like Nick’s, is pretty and slight and wears a blond pageboy.

Jon is sitting in his father’s Homeland sunroom, fiddling with two stubby screwdrivers, one slotted and one Phillips-head. He’s talking about Jim Harrison. “When I was a sophomore in high school, I knew he was full of crap,” says Jon, remembering Jim’s attempts to be cordial, to act like a family. “I said, ‘Wednesday night I was picking my mom up from your house, telling you to stay the hell away from her. I’m not going to make nice with you on Sunday.”‘

Police say that Susan’s killer is better off revealing her whereabouts now. “When that person is able to admit that they’ve done something, there’s a huge sense of relief,” says Lieutenant Sam Bowerman. Besides, he reminds any guilty party who’s reading, a cooperative killer might face a lighter sentence: “Once we find the body, we won’t be interested in your side of the story.”

So if Jim Harrison knows where Susan is, and if he reveals this and ends her family’s restless search, will Jon be grateful? Will Jon feel mercy?

“I will never, never, never, ever, ever, regardless if he got ripped to pieces by wild wolves, never feel a moment of care for what happens to him,” says Jon, who is studying to become a prosecutor.

As he speaks, he slides one screwdriver absently against the other, as if he’s sharpening a knife.

(At the Turf Inn)

THE REPORTER: Most of the people I’ve talked to are really upset that they don’t know where her body is. It hurts them to think of her not getting a proper burial, not having a tombstone for people to visit. Do you ever think about that?

JIM: Oh, my God. That’s terrible. I’ve been praying so hard that she comes home. I haven’t really thought about that.

THE REPORTER: You don’t wonder where her body is?

(Jim stares at the reporter. The reporter stares back until the waitress comes.)

Editor’s Note: Since this story’s publication, Susan’s remains were found in rural Frederick County by two hikers on November 29, 1996. Her death was subsequently ruled a homicide by the state medical examiner, but Harrison was never arrested, tried, or charged. After two years of handling the case, the Maryland attorney general’s office called off the criminal investigation into her death due to ”insufficient evidence.” A wrongful death lawsuit filed by Susan’s sons against Harrison ended with a confidential settlement.

In the fall of 2007, Harrison died of pneumonia at the age of 71.