Arts & Culture

Constant Gardener

As the times and terrain change, the Meyer Seed Company remains rooted in Baltimore.

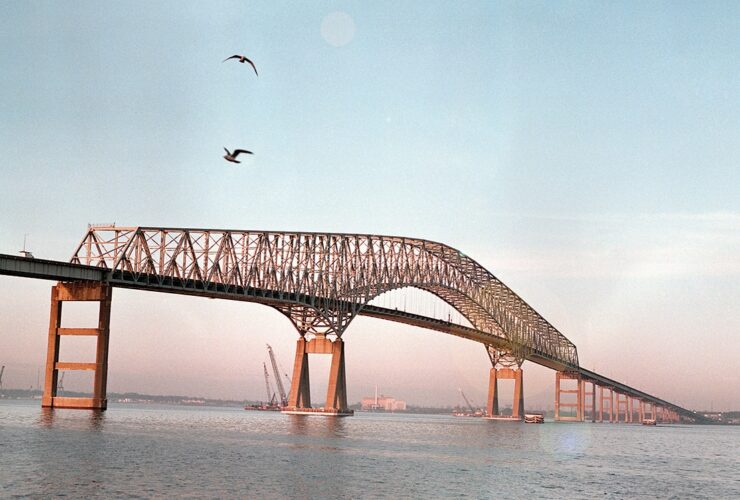

all started with light rains, which arrived in the afternoon, a dose of weather usually welcome at the end of summer, though not once the storm picked up, and that night, the city streets began to flood. Under the cover of darkness, water rose above the harbor’s seawall, submerging park benches and parked cars, while beating winds toppled trees and left a million people without power. The high tide filled basements and living rooms and businesses, with Hurricane Isabel eventually seeping under the old steel doors of the Meyer Seed Company.

all started with light rains, which arrived in the afternoon, a dose of weather usually welcome at the end of summer, though not once the storm picked up, and that night, the city streets began to flood. Under the cover of darkness, water rose above the harbor’s seawall, submerging park benches and parked cars, while beating winds toppled trees and left a million people without power. The high tide filled basements and living rooms and businesses, with Hurricane Isabel eventually seeping under the old steel doors of the Meyer Seed Company.

In the morning, owner Harry Hurst surveyed the damage done to his family business in Fells Point. Inside, where the storm surge had reached upward of four feet, his warehouse, still under water, had turned to goulash, much of the fall inventory wet and ruined, including thousands and thousands of seeds. Giant pallets of topsoil had been lifted like feathers and floated around the sprawling storeroom, and heaps of cardboard boxes had not just started to disintegrate, but ferment.

“It was hell,” says Hurst, 16 years later. “You just don’t realize how much damage water can do.”

“We got destroyed, lost a lot of stuff,” says Butch Dingle, a longtime warehouse employee. “We thought Meyer Seed was through.”

But the company’s customers and vendors came to their rescue, replacing unsalvageable goods, deferring payments, even rolling up their own sleeves to help clean up after the water finally went back out to sea. It was a testament to the goodwill of this century-old seed business that has weathered much. Not just natural disasters, but also, over its nearly 110 years, times that have radically changed.

Harry Hurst stands with his father, Web.

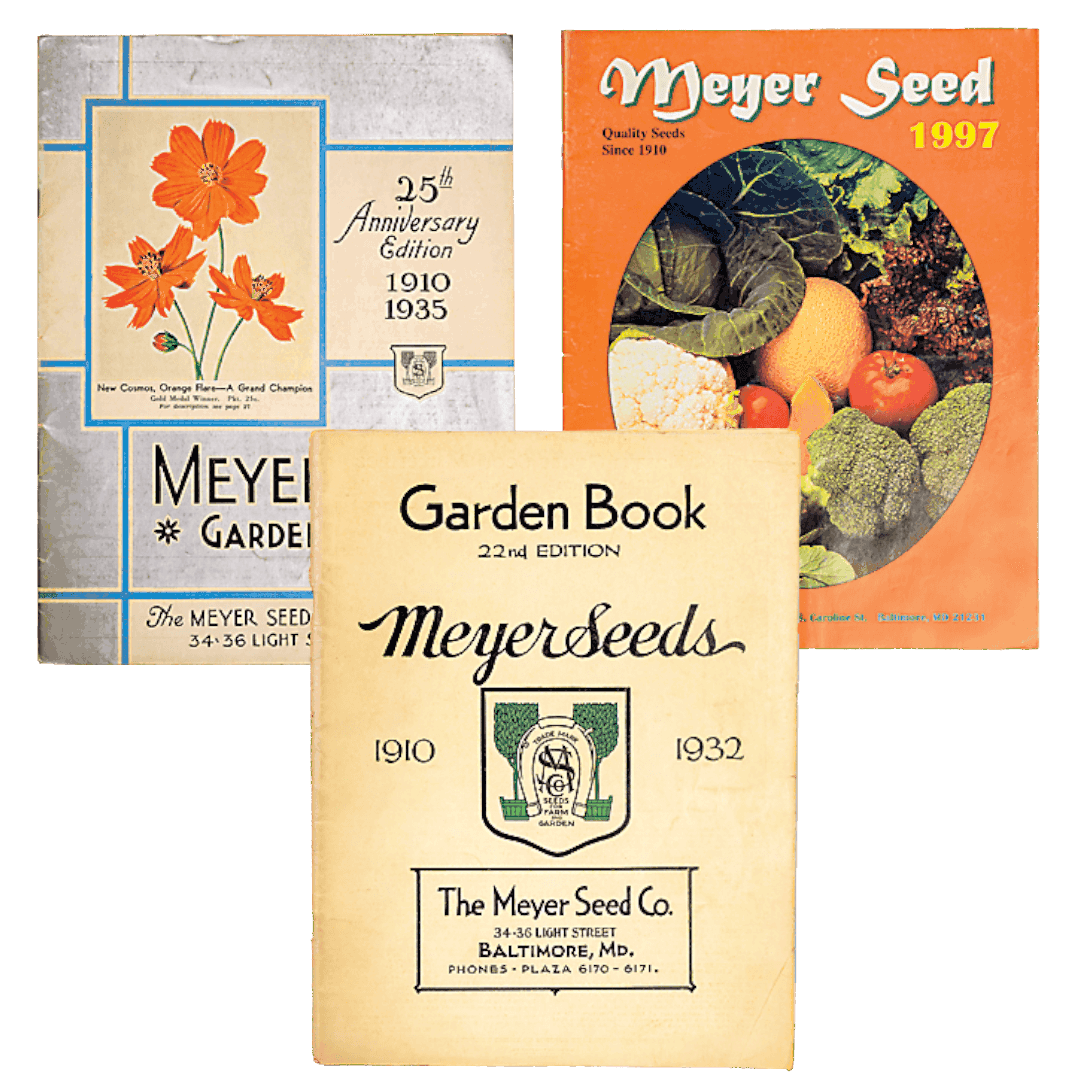

old garden book catalogs.

Today, Harry and his employees will tell you that it’s those customers who have kept them afloat over the years. Although, of course, when Meyer first opened its doors in 1910, there were many, many more of them.

Back then, it was actually the Meyer-Stisser Seed Company, with founder John Meyer and his partner, G.W. Stisser, forming one of the many seed companies that speckled the city in those days. There was the long-established Bolgiano’s, a block south downtown, and J. Mann’s & Co. in Old Town, who were direct competition with fruits and vegetables. There was the Belt Seed Company in the Inner Harbor, too, and William G. Scarlett & Company with its Oriole Brand corn in Little Italy, who both specialized in lawn and field seeds. Meyer-Stisser was on the corner of Light and Lombard, a hefty brick building out of which they sold a cornucopia of garden varieties.

Much from that period has been lost to history, but faded catalogs live on to show that, from the get-go, Meyer-Stisser set themselves apart with an enthusiastic emphasis on customer satisfaction. Their motto back then was “punctuality, sterling quality, courteous treatment,” which was recognized by patrons who wrote such glowing reviews as “one of the most reliable [stores] in existence” and “one of the rarest of all things in the business world, a firm always willing to back up any guarantee given, and do it both quickly and cheerfully.”

For many generations, it's the stuff of childhood–the dusty smell of earth ever-present, as well as the potent possibility of all it could grow.

Of course, business was good then, in part, because this was a time when we grew our own food, especially during the two World Wars, when gardening was even considered part of the war effort to stave off food shortages while the men were away. Those who didn’t grow bought direct from farmers at one of the city’s many public markets—Lexington, Hollins, Broadway, Belair, to name a few—where dozens of open-air vendors hawked perfectly piled produce to ladies in coiffed hair and petticoated skirts.

SEEDS ARE PACKAGED BY HAND BEHIND THE COUNTER; BIRD HOUSES AND FEEDERS HANG FROM THE SHOP CEILING.

Eventually, Stisser returned to his native Germany, and in the 1930s, Meyer was bought out by his assistant, Webster Hurst Sr., whose father had been in the grain and feed business before him, though the company name remained. Decades later, Hurst’s son—and Harry’s father—Web Jr. would take over, relocating to the corner of Caroline and Fleet Streets in 1969, where today, from the looks of it, little has changed.

Outside, the same weathered signs from the Light Street location hang on the brick-and-cinderblock exterior, declaring “quality” seeds inside. Past the bamboo windchime that serves as a doorbell, the small front shop features packets upon packets of colorful seeds—beets, radishes, carrots, kale, pumpkins—plus aisles of fertilizers with funny names like fish meal and bat guano, and walls decorated in rakes and shovels. Bins brim with starter potatoes and onions, and above them, bird houses hang from the ceiling, waiting for future residents, while oversized goldfish take laps around a miniature koi pond on the linoleum floor.

For many generations, it’s the stuff of childhood—the dusty smell of earth ever-present, as well as the potent, almost magical possibility of all that it could grow. “There are so many things to learn here,” says shop employee Leslie Stewart from behind the worn wood counter. “For every customer, there’s something new to take away, coworkers have backlogs of information, and every growing season is different. The weather is typically small talk in other places, but it’s the only thing we talk about here.”

MEYER PEOPLE, PLACES, AND PRODUCTS, PAST AND PRESENT.

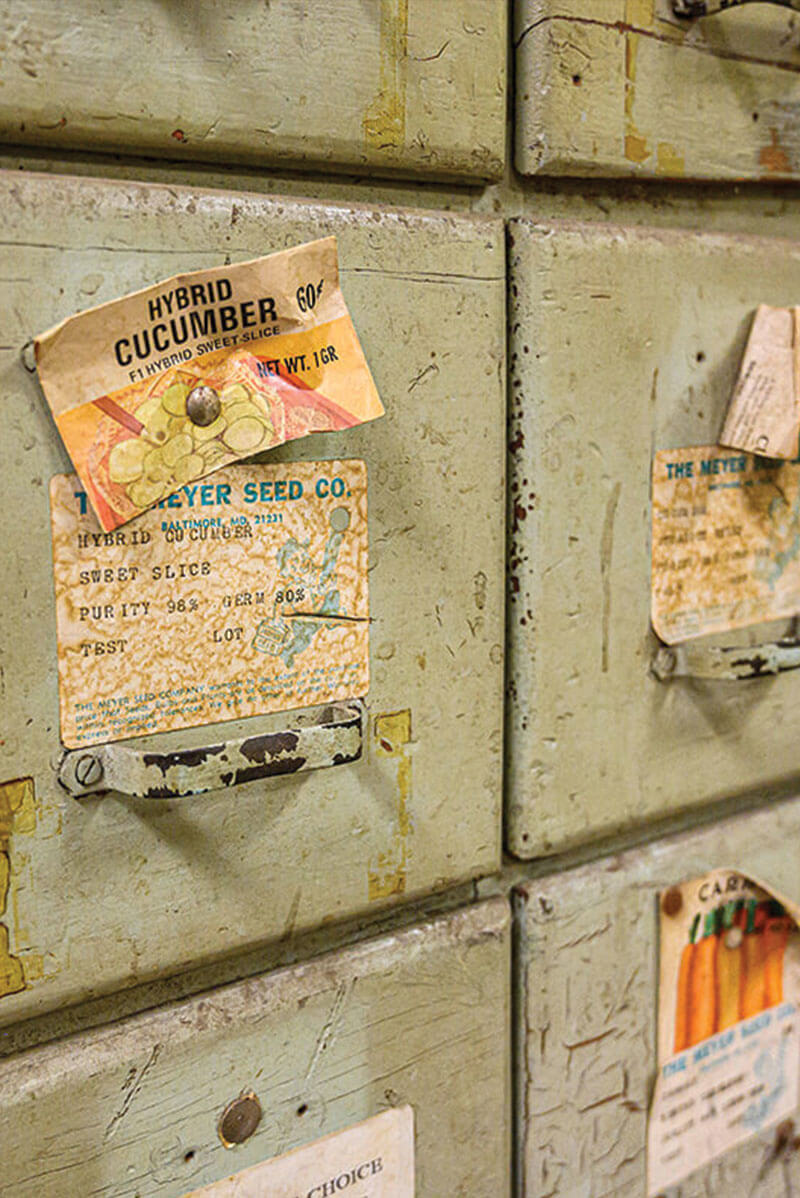

Behind her, a fluorescent hallway leads past two bustling offices to the back seed room. Here, shelves are stocked with bags and boxes of everything from beans to flower seeds, which are all, for the most part, sorted, mixed, bagged, and stored by hand, with the help of a few machines they now operate, too.

“The vegetable seeds come in around Christmas, and then I pack it all up for the next year,” says Nicole Tamburello, who singlehandedly tends to this large portion of the roughly 1.5 million pounds of seeds they purchase annually, mostly from states out west, where the cool, dry climates are more suitable for consistent growing. “This time of year, the onions come in, then the rhubarb, then the garlic and potatoes. For spring, I start with the limas, then the peas, then the corn, then I move onto everything else. You always have to be ready for what comes next.”

Past the seed room is the warehouse—all 50,000 square feet of it—a cavernous space with stories-high ceilings, teetering towers of inventory, and the shadows of what the city’s harborfront industry might have looked like even just a half-century ago. Light pours in through opaque windowpanes, and forklifts beep in the background as the morning rush winds down.

This time of year, Dingle and Kevin Barkley, who helps manage the warehouse, consider the place pretty much empty, even as the maze of wooden pallets, piled with 50-pound bags of seeds and soil, reaches up toward the cobwebbed rafters. But come January, it will be literally packed with products for the upcoming season, as they’re always working ahead, gearing up for fall in the dead of summer, or soaring through spring orders in the bitter heart of winter, which in this old building keeps the guys warm—pulling orders, loading trucks, unloading tractor trailers, organizing the wares while the last few shop cats skitter about in search of any trespassing rodents.

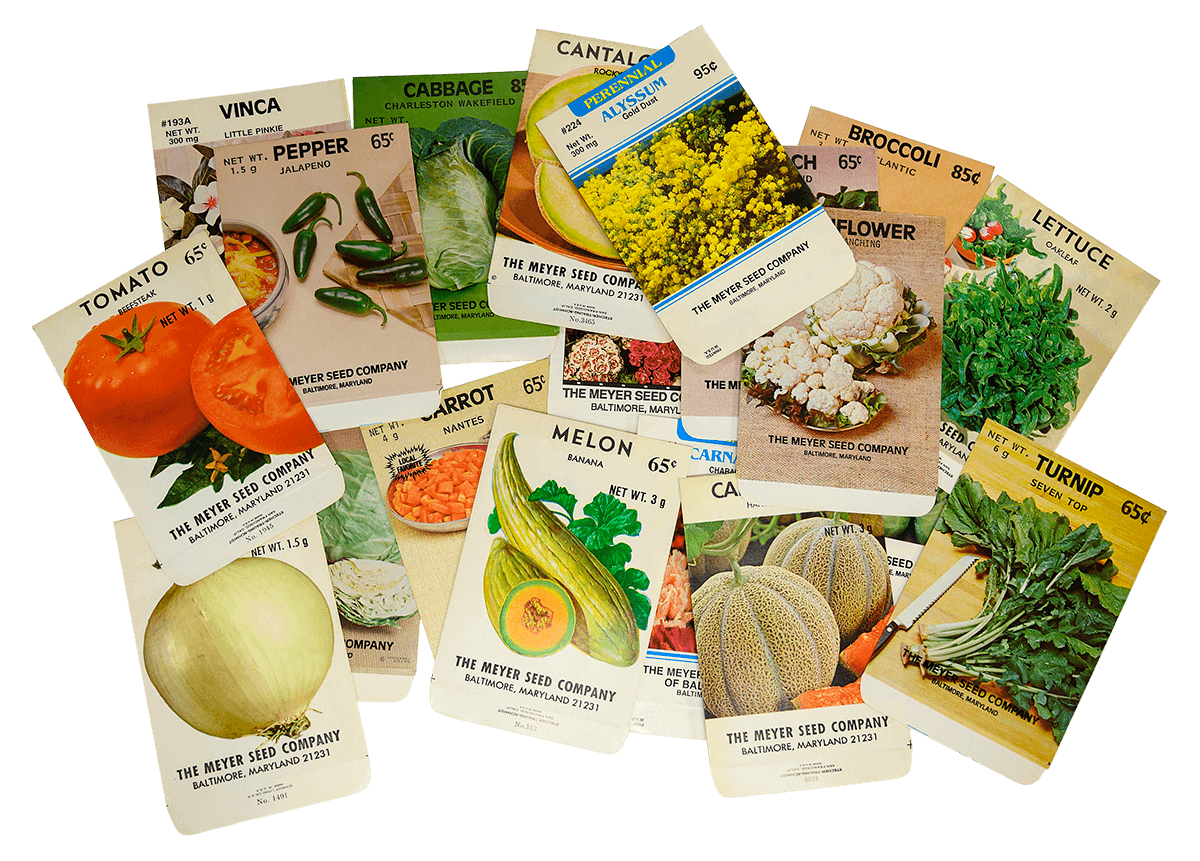

VINTAGE SEED PACKETS.

Whatever the season, their best-selling product continues to be birdseed—“People love it so much, sometimes I think the customers eat it themselves,” says Dingle—with sacks of sunflower seed, thistle, and peanut splits stacked waist-high to be mixed into custom blends for clients. These have proven particularly popular, especially as the market continues to change.

“The biggest change came with the Walmarts and Home Depots,” says Barkley. “Back then, we worked with more independent retailers, and the mom-and-pop stores just couldn’t compete. Those guys can buy more volume, drive the price down, and knock the little man out of business. But we’re still surviving, still hanging in there. You can’t find anything else like us in the city, or state.”

Back in Web’s day, having joined his father as a salesman after the end of his service in World War II, Meyer Seed also worked directly with the region’s bounty of growers. “On Saturdays, we’d go down to the markets and meet the farmers, take orders, put them up, and bring them back—same-day delivery,” he says with a firm nod and puckish smile.

The weather is typically small talk in other places, but it's the only thing we talk about here.

“The focus was on the farmer then,” says Harry. “Throughout the years, as that’s changed with fewer and fewer farmers, the focus has shifted to retail and wholesale—independent garden centers, nurseries, hardware stores. No chains. You lose your identity when you start selling to them.”

It was Web’s decision to not get into bed with the big-box stores back in the 1980s because they were busy, even as most of the other seed companies continued to close. Just a few years earlier, Harry had come onboard and witnessed one of the business’ boom times, renewed in part by the rise of Earth Day and the environmental movement of the 1970s, with stacks of orders coming in every week. “We thought we were recession-proof,” he says, “that people were always going to garden.”

But on and off over the decades, as the food industry shifted to mass production and processed goods, away from the local farmer, and as hobbies moved indoors, out of the dirt, many people did indeed stop gardening, and perhaps even more importantly, stopped passing the practice on to the next generation. “I don’t think anyone has figured out the younger people or online shopping yet,” says Harry. “It’s a huge challenge for everyone, and what affects our customers affects us.”

The Meyer warehouse.

Meanwhile, most of the remaining farmers—by most recent counts, there are now some 12,000 farms in Maryland that make up just under two million acres, compared to 46,000 and more than 5 million, respectively, around the time that Meyer opened—switched from the once-favored fruits and vegetables to less diverse but more in-demand crops like corn and soybeans.

Meyer’s fall trade show, where they invite customers and vendors together and gather orders for the upcoming year, has softened the blow, with each helping the other. They’re buoyed by these loyal relationships, with many being old family businesses themselves who have worked with the seed company for decades, though word of mouth continues to be a viable lifeline, too. “Most city growers know about us and pass it on from gardener to gardener,” says John Kozenski, storefront manager, though the walk-in customers are few and far between. “That we’re the best-kept secret in Baltimore.”

“This is not corporate America,” says Peter Goodman, a customer service rep, who still writes orders by hand. “We still deal with people, and the same people on a consistent basis. Being a smaller operation has its advantages.”

For starters, “You don’t have to go all the way up the chain to get things approved,” says office manager Tina Adams, whose father worked for Meyer on Light Street. “If somebody needs something special, we just go right over to Harry’s desk.”

“And if they need something, we try to get it for them as soon as possible,” says Hilda Geiger, the office clerk for the last 31 years. “There’ve been a lot of changes, but Web and Harry have always been good to me.”

The Meyer Crew.

Though he’s now in his mid-90s, Web still comes to the office five days a week, donning thick glasses and a crisp plaid button-up, a trio of pens at the ready in his breast pocket, while Harry runs the day to day, overseeing the company’s two dozen employees.

“The seed business’s changing, but it’s progress, that’s all,” says Web matter-of-factly. “I just don’t know how all these young fellas are affording all these new condos—they’re awful expensive.”

What he means is, though Meyer still looks much like it used to, the neighborhood around them has become almost unrecognizable. Once a hub for local manufacturing, the warehouses and work yards have slowly, then swiftly, been replaced by boutique gyms, organic grocery stores, fine-dining restaurants, and towering above them all, glitzy high-rise apartment buildings. The seed company and its neighbor across the street, H&S Bakery, might be the last vestiges of the northern harbor’s once-thriving past.

“In some respects, it’s gotten better,” says Harry, “and in others, maybe not so much—traffic and parking continue to be terrible.”

Over the years, developers have expressed interest in the building, but the Hursts have no plans to sell. “We own it, we don’t have to pay rent to someone else, and it’s pretty close to the main thoroughfares for our drivers, so it just works,” says Harry, though the future is still in limbo, with his kids not interested in carrying the torch. “We’re just taking it year by year.”

In early August, another summer storm brought back old memories as rains lingered, and the waters again rose around Fells Point and Harbor East, overflowing into homes and businesses, and even causing a fire in one vacant building. Luckily, this time, the flooding stopped at the top of the Meyer loading dock, sparing them from a second close-call. The seed room’s sage-green storage cabinets are still warped from Hurricane Isabel.

But weather is something they’re used to around here, because in the seed business, you’re always at the whims of Mother Nature. Besides, they’ve purchased flood insurance, which might continue to come in handy in a neighborhood that’s projected to be adversely affected by more storm surges in the future. Despite the odds, they plan on sticking around, and there’s no reason to believe otherwise.

“We’ve been here a long while,” says Geiger from behind her desk, her beehive perfectly pinned, surrounded by work still left to do. “I was at the grocery store the other day and saw a couple looking at the tomatoes. The man was saying how we used to save seeds, how you can’t buy them around here anymore. I turned around and said, ‘Oh yes, you can—at Meyer Seed!’ He said, ‘Are they still in business?’ And I said, ‘Oh yeah, right down on Caroline Street . . . Meyer Seed is still there.’”