News & Community

Parting Words

We say goodbye to the notable Marylanders we lost in 2013

Judge Elsbeth Bothe, 85

In her more than 20 years as an activist criminal defense attorney, Elsbeth Bothe made no secret of her determined liberal streak, defending civil-rights workers in Mississippi and, locally, protestors trying to end Gwynn Oak amusement park’s whites-only policy. She also served as an assistant public defender for the state and as the American Civil Liberties Union counsel.

And she made no secret of her distaste for capital punishment, writing in a 1976

Sun op-ed piece, “Incidence of murder bears no relationship to the existence of the death penalty.” Nonetheless, upon her ascension to the city’s Circuit Court in 1978, she pledged to follow the letter of the law, despite her personal aversion to capital punishment—and she did so up until her 1995 retirement.

A girlhood interest in true crime manifested itself later in her preference for murder cases—she sometimes lobbied other judges to trade their murder trials for one of her less-heinous-offense assignments—and she amassed shelves of books on the subject of homicide.

“She was like a character straight out of a Genet novel, if he hadn’t been such an angry writer,” says filmmaker John Waters, her longtime friend. “What other judge decorated her chambers with human skulls and scary hangmen, yet fought for civil rights and was against capital punishment? Her epitaph should read ‘She Sure Was Something!’”

Tom Clancy, 66

Tom Clancy wrote 26 books in 28 years, 17 of which topped The New York Times’ best-seller list, with more than 100 million copies extant. Five of his novels featuring his principal protagonist, the patriotic-to-the-core Jack Ryan, were adapted into mega-box-office Hollywood films; several of his books were retrofitted into popular ultra-realistic video games.

Tom Clancy wrote 26 books in 28 years, 17 of which topped The New York Times’ best-seller list, with more than 100 million copies extant. Five of his novels featuring his principal protagonist, the patriotic-to-the-core Jack Ryan, were adapted into mega-box-office Hollywood films; several of his books were retrofitted into popular ultra-realistic video games.

All of this made Clancy extremely wealthy. He purchased an 80-acre Southern Maryland farm with a view of the Chesapeake, a 17,000-square-foot aerie in downtown’s Ritz-Carlton (price: $16.6 million), a big chunk (24 percent) of the Orioles, and a surplus Army tank. Pretty remarkable for a man who spent more than 20 years slaving as an insurance salesman before publication of his first novel,

The Hunt for Red October, in 1984. Just as remarkably, that book completely transformed the thriller genre, as Clancy larded it—and his subsequent novels—with a geeky verisimilitude (technical descriptions of small-scale weaponry, large-scale military hardware, international spy agencies) that registered with readers. Wrapped around these details: compelling, intricately woven tales of global intrigue, mayhem, and valor.

“Clancy had a good understanding of the big picture with regards to his core Jack Ryan narratives,” points out Bill U’Ren, assistant professor of English at Goucher College’s Kratz Center for Creative Writing. “He was shrewd enough to move Ryan through a range of conflicts while others of his genre trapped themselves in the Cold War milieu.”

Richard Ben Cramer, 62

Red-bearded, cigar-chomping Richard Ben Cramer cut a distinctive swath from his time as editor of Johns Hopkins’ student-run News-Letter through his career as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun and The Philadelphia Inquirer, national magazine freelancer, and author of 1992’s What It Takes, his doorstop-sized account of the 1988 presidential campaign.

Red-bearded, cigar-chomping Richard Ben Cramer cut a distinctive swath from his time as editor of Johns Hopkins’ student-run News-Letter through his career as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun and The Philadelphia Inquirer, national magazine freelancer, and author of 1992’s What It Takes, his doorstop-sized account of the 1988 presidential campaign.

Not yet 30, he copped a Pulitzer Prize in 1979 for incisive, innovative, immersive reporting for the Inquirer on the complex political events embroiling the Middle East. His 1984

Esquire profile of William Donald Schaefer (whom Cramer called “Mayor Annoyed”) adroitly portrayed the occasionally prickly city chief exec. And while poorly received when first published, his What It Takes has since attained revered status.

“Cramer was legendary in

The Sun newsroom, and his career there was not without some, um, infamous moments,” recalls acclaimed mystery novelist and ex-Sun staffer Laura Lippman. “But he wrote a book that might be the last of its kind. If there is an afterlife, I like to think he’s hanging out with William Donald Schaefer.”

Mary Corey, 49

When veteran

Baltimore Sun staffer Mary Corey took over as newsroom boss—officially, she was senior vice president and director of content—in 2010, morale at the city’s paper of record had plummeted to an absolute nadir in the wake of massive layoffs and buyouts in the previous two years. The term “newspaper morgue” had assumed a whole new significance. But through a potent combination of her well-honed editorial, administrative, and social skills, Corey led the decimated staff out of the abyss.

In 2012,

The Sun copped the Newspaper of the Year award from the Maryland-Delaware-D.C. Press Association, along with a fistful of other top prizes in the competition. Additionally, Corey resurrected The Sun Magazine 14 years after its demise, and injected the Sunday paper with useful, engaging newsy features pertaining to medicine, science, federal government employment, and ongoing Sun investigations.

“Mary’s success as a journalist—from intern to top editor—drew on her many gifts: an ability to become interested in just about anything, a charm that disarmed people and got them talking, an A-student’s diligence and drive, the joy of telling a story,” notes Rebecca Corbett, senior enterprise editor for

The New York Times and Corey’s friend. “That she was doing it in her hometown, a place she knew and loved—this was a woman who chose to live in a row house, after all—made the journalism all the richer.”

Rev. Vernon Dobson, 89

As a minister, community activist, and, not least, civil-rights leader, Vernon Dobson advocated and agitated for equality, fairness, and justice for all Baltimoreans, especially its poor, for more than a half-century.

A prominent member of the “Goon Squad”—a group of black leaders that also included Parren Mitchell, Madeline Murphy, and Rev. Marion Bascom, among others—Dobson helped desegregate the city’s Gwynn Oak amusement park in 1963, and, later that year, aided Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in organizing the historic March on Washington. Two years later, he joined King in one of the civil-rights movement’s signature events, the march from Selma to Montgomery in Alabama.

Back in Baltimore, Dobson teamed with developer James Rouse to help establish the Maryland Food Bank in 1968, after riots following King’s assassination decimated vast areas of the city. And in 1977, he co-founded BUILD (Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development) to administer to the everyday needs of the city’s underserved population, in the process reviving the Sandtown neighborhood near his parish, West Baltimore’s Union Baptist Church, and working toward passage of living-wage legislation in the city.

“Vernon Dobson was a man who was larger than life itself—in his body, with his booming voice, in the way he used words,” says WEAA talk-show host Marc Steiner. “He put his life on the line to end segregation, for civil rights and human rights, and for his parishioners.”

Edward Dopkin, 61

By the time Eddie Dopkin hurtled to the head of the local restaurateur class in 2005 with his unpretentious, Southern-inflected Miss Shirley’s breakfast spot, he already had logged 30-plus years in the catering/dining business. Starting in the 1970s, Dopkin learned what worked and what didn’t at his parents’ Beef Inn.

By the time Eddie Dopkin hurtled to the head of the local restaurateur class in 2005 with his unpretentious, Southern-inflected Miss Shirley’s breakfast spot, he already had logged 30-plus years in the catering/dining business. Starting in the 1970s, Dopkin learned what worked and what didn’t at his parents’ Beef Inn.

He went out on his own at Harborplace in the 1980s with the Bagel Place——simultaneously leading the twin pavilions’ first merchants’ group——which grew to include multiple Baltimore-Washington locations, and in the 1990s/2000s built a North Baltimore restaurant empire: Tex-Mex-y Loco Hombre; the adjacent Alonso’s Pub; and the instantly successful Miss Shirley’s, which moved to a larger spot nearby to accommodate adoring fans before adding outposts downtown and in Annapolis. Dopkin put S’ghetti Eddie’s in the former Miss Shirley’s space.

“Eddie Dopkin was a visionary who cared about the success of the restaurant industry as a whole,” says Marshall Weston Jr., president/CEO of the Restaurant Association of Maryland. “He understood the value of all Baltimore restaurants doing well, not just his own.”

Art Donovan, 89

Art Donovan lived—and played—large. The Baltimore Colts’ defensive lineman ate prodigiously unhealthful meals: hot dogs, cheeseburgers, and pizza, chased by beer. He made spectacularly huge plays: His crucial tackle preceded the Colts winning drive in the 1958 NFL championship game. And he recounted hilariously gargantuan tales about himself, professional football, and, as he once characterized them, “the oversized coal miners and West Texas psychopaths” who played it.

Art Donovan lived—and played—large. The Baltimore Colts’ defensive lineman ate prodigiously unhealthful meals: hot dogs, cheeseburgers, and pizza, chased by beer. He made spectacularly huge plays: His crucial tackle preceded the Colts winning drive in the 1958 NFL championship game. And he recounted hilariously gargantuan tales about himself, professional football, and, as he once characterized them, “the oversized coal miners and West Texas psychopaths” who played it.

Deceptively agile for 270 to 300 pounds, Donovan batted aside his offensive counterparts to ruthlessly yank down opposing teams’ running backs and quarterbacks from 1950 through the 1961 season, earning Pro Bowl status five times and helping the Colts win back-to-back NFL championships in 1958 and 1959.

Out of football, he owned liquor stores and Valley Country Club in Towson, and, upon publication of his successful 1987 autobiography, Fatso, he found a national audience for a second time as a self-effacing, Runyonesque raconteur on a handful of TV talk shows, including 10 appearances on Late Night with David Letterman, who clearly relished Donovan’s instinctual delivery and humor.

“In a city of everymen, Artie Donovan personified Everyman,” says Stan Charles, founder and publisher of PressBox. “He was a splash of color when pictures were still black and white, and he somehow became even more colorful as time allowed the full body of his life to show its rich textures.”

Jack Germond, 85

An unapologetic old-school journalist, Jack Germond doggedly covered national politics, including 10 presidential elections, from his base in Washington, D.C., as a reporter, editor, columnist, author, and media pundit for the final 44 years of a five-decade career. He first gained renown on his own as political editor of

The Washington Star, and, more famously, from 1977 until 2000, with his five-days-a-week “Politics Today” column writing partner, Jules Witcover, at the Star, Evening Sun, and Baltimore Sun.

Equally unapologetic about his liberalism, Germond held forth as a quick-thinking talking head on a passel of TV public affairs programs, most notably The McLaughlin Group.

“Jack Germond was not only a columnist——he was a reporter-columnist,” notes Baltimore Sun writer and WYPR talk show host Dan Rodricks. “He worked the phone, he worked the room, and he and Jules Witcover knocked it out, day after day, year after year——smart and timely commentary based on fresh reporting, zero-tolerance for political BS, and decades of knowledge between them.”

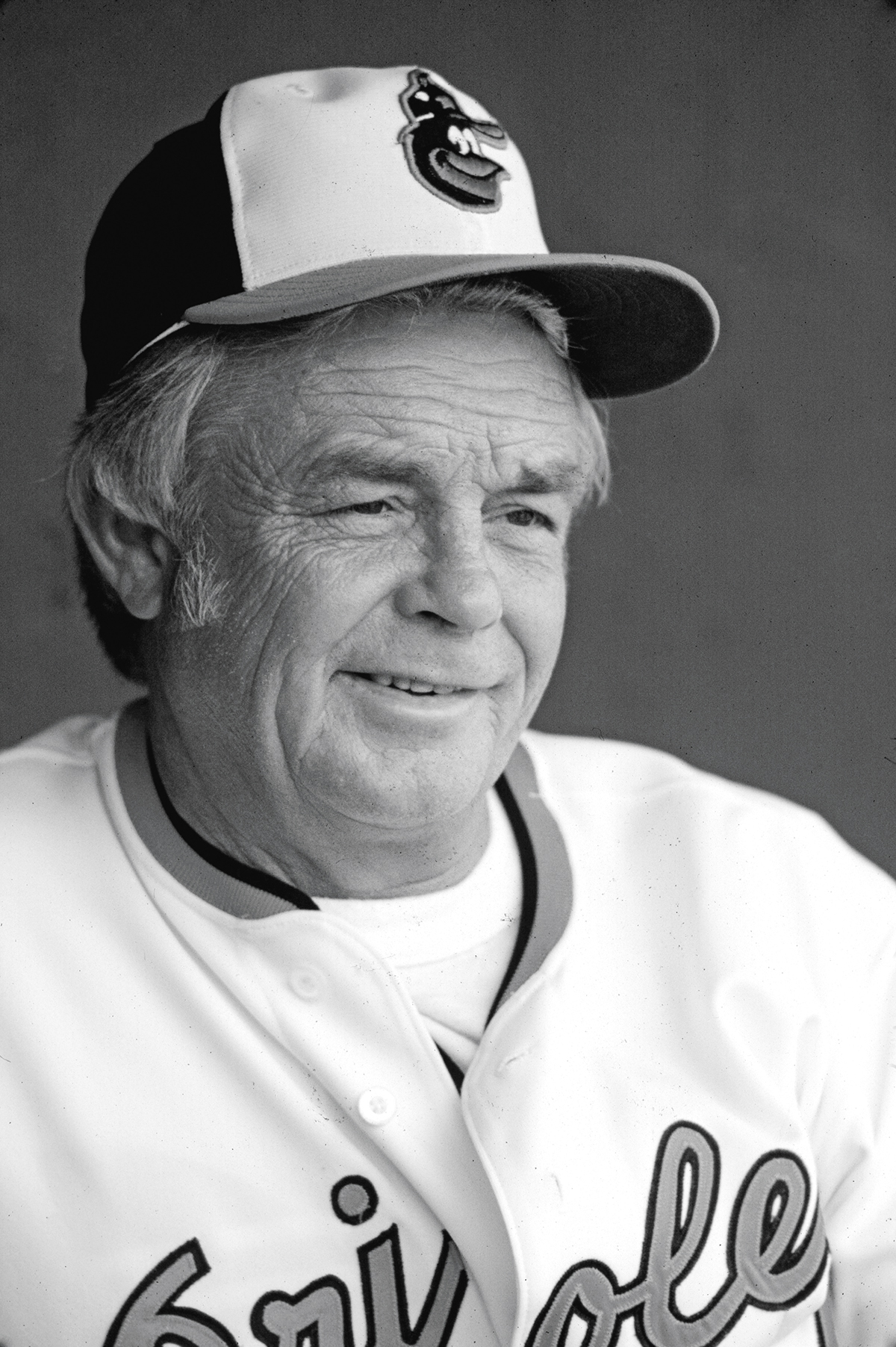

Earl Weaver, 82

While Earl Weaver’s oft-quoted mantra for winning—“pitching, defense, and the three-run homer”—serves as a useful encapsulation of his baseball philosophy, it conveniently obscures the complexity, insight, innovation, resourcefulness, and sheer brilliance that made him not only the best manager in Orioles history but also among the best ever in baseball.

While Earl Weaver’s oft-quoted mantra for winning—“pitching, defense, and the three-run homer”—serves as a useful encapsulation of his baseball philosophy, it conveniently obscures the complexity, insight, innovation, resourcefulness, and sheer brilliance that made him not only the best manager in Orioles history but also among the best ever in baseball.

Same goes for the raw statistics: In his 17 years here, he shepherded the Orioles to five 100-win (or more) seasons, four American League championships, and four World Series appearances, winning one, in 1970; but the numbers omit how he accomplished those feats. With astounding consistency, Weaver coaxed the maximum performance from each of his available 25 players—the stars (Jim Palmer, Brooks Robinson, Boog Powell) and the lesser mortals (John Lowenstein, Rick Dempsey, Tippy Martinez)—to fashion formidably versatile teams. Presciently in the pre-computer era, he used comprehensive statistics, compiled on fraying index cards, to devise strategy and execute it in crucial game situations. Not forgetting his pyrotechnical encounters with umpires, resulting in a record-setting 91 ejections.

“Managing is not like playing baseball,” Weaver told author Louis Berney for his 2004 book, Tales From the Orioles Dugout. “Maybe if I was the type of guy that didn’t care if we won or lost, it would have been a different situation. But that’s why I went crazy with umpires. Because we have to win. We have to win. I’m that kind of guy.”

Blaster Al Ackerman, 74

Something of an éminence grise to the city’s cultural underground, his subtly subversive and disarmingly frolicsome writing and visual/spoken art tapped into the subcultural pulse via a blizzard of mail-art and small-press works to explore various dark-hued phenomena, particularly madness.

Donnie Andrews, 58

West Baltimore drug dealer, robber, and murderer (for which he was sentenced to a life term) renounced his thuggish ways, cooperating with authorities to eradicate a drug gang. His life served as a model for the Omar Little character on David Simon’s Emmy-winning, set-in-Baltimore drama

The Wire.

Judge Howard Gary Bass, 70

Brought a gentle sense of whimsicality and a comfortable environment to proceedings during his 29-plus years on the Baltimore District Court bench——for plaintiffs, defendants, and their attorneys——earning him this magazine’s award for “Best Traffic Court Judge” in 1995.

Paul Blair, 69

Orioles center fielder.

Our remembrance is here →

Phyllis Brotman, 79

Exuberant, savvy, and versatile public relations/advertising/marketing exec successfully represented an array of A-list clients, notably Black & Decker and CareFirst, as well as the city itself as a key member of Mayor William Donald Schaefer’s inner circle. Also served as the first woman president of The Center Club and played a key role in launching MPT.

Rev. Dr. Harold A. Carter Sr., 76

As pastor of West Baltimore’s New Shiloh Baptist Church for nearly five decades, he oversaw its expansion to include senior housing, a children’s center, music school, and theological institute, while also vigorously advocating for the civil/political/economic rights among the city’s disenfranchised.

Robert Chew, 52

Actor and educator appeared on David Simon’s

Homicide and The Corner before memorably embodying intimidating drug kingpin Proposition Joe on Simon’s The Wire. Additionally, he taught young actors at the Arena Players Youth Theatre, guiding 22 of them in their roles during season four of The Wire.

John Coolahan, 80

First in the House of Delegates (1967-1970) and then during two stretches in the State Senate (1971-1978, 1983-1986) representing Southwest Baltimore County, he tilted right politically, strongly pushing for a state lottery and vociferously opposing a city light-rail system. Served as a District Court judge after his General Assembly tenure.

Gerald Curran, 74

Congenial old-school politician from storied office-holding Irish Catholic family, quietly but effectively represented Northeast Baltimore in the House of Delegates from 1967 to 1998, advocating vigorously in favor of state aid to parochial schools.

Dr. John Dennis, 90

Helped transform the University of Maryland Medical School into a premier institution as its dean from 1973 to 1990, emphasizing biomedical research, clinics, and basic sciences, while spearheading the construction of a new downtown Veterans Health Aministration hospital.

Isaiah “Ike” Dixon, 90

As a four-term member of the House of Delegates representing Baltimore City in the 1960s and 1970s, serious-minded legislator championed insurance-industry issues and guided a bill to passage that elevated the state’s cross-burning law from misdemeanor to felony.

Joseph Eubanks, 88

Acclaimed bass-baritone toured the world in a mid-1950s production of Porgy and Bess, before settling in as a Morgan State University professor from 1962 to 1985, teaching voice, opera, and music theory, while directing the school’s two musical theaters and its choir and performing locally.

Youman Fullard Sr., 73

Cheerfully served up heaping mounds of heart-stopping soul food——fried chicken, short ribs, candied yams——as co-owner/operator (along with his wife) of Greenmount Avenue’s Yellow Bowl Restaurant, attracting visiting celebs as well as a stream of local politicians, who treated the place as their clubhouse.

Rita Marie Furst, 94

The 1981 murder of her husband spurred her to advocate on behalf of crime victims, notably co-founding the Maryland Coalition Against Crime. Her efforts led the General Assembly to pass legislation that ensured families be apprised of convicted criminals’ parole status and permitted family members to give impact statements at sentencing.

Otis R. “Damon” Harris Jr., 62

After performing with several Baltimore vocal groups, he replaced Eddie Kendricks as lead tenor with The Temptations in 1971. During his four-year stint, they scored a national No. 1 hit with “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone.” Later, he worked tirelessly to raise awareness among African-American men of their high risk for prostate cancer.

Hattie Harrison, 84

Represented East Baltimore in the House of Delegates from 1973 until her death——the chamber’s longest-serving member——chairing its Rules & Executive Nominations Committee while actively crusading for education, assault-weapons control, and social justice for minorities and women.

Christopher Hartman, 67

Boisterous press spokesman for Mayor William Donald Schaefer kept his boss and the city in the national spotlight, famously staging the mayor’s dip in the National Aquarium’s seal pool wearing a Gay-Nineties swimsuit and straw hat while clutching a rubber duck. Earlier, he launched the City Fair.

Jean Hill, 67

City schoolteacher went on to become a plus-size greeting card model while acting, directing, and designing costumes for Arena Players. Achieved cult-star status in John Waters’s 1977 film

Desperate Living as murderous maid Grizelda Brown, followed by appearances in his movies Polyester and A Dirty Shame.

Shirley Howard, 88

After enjoying minor celebrityhood on local TV in the 1950s, she established the Children’s Cancer Foundation with her husband in 1984, raising millions of dollars to fund research at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, University of Maryland Medical Center, and the National Cancer Institute, among other institutions.

Richard Hug, 78

Personable founder/CEO of air-pollution moderation firm raised millions of dollars for state Republican Party candidates, including gubernatorial runs by Ellen Sauerbrey in 1998 and Robert Ehrlich in 2002 and 2006; also oversaw Maryland fundraising for George W. Bush’s two presidential campaigns.

Leonard Kerpelman, 88

Activist attorney represented atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair in her case against mandatory prayer in Maryland’s public schools, shepherding the case to the Supreme Court, which, in 1963, ruled in his client’s favor, outlawing the practice. Later worked for divorced fathers’ equal rights in custody cases.

Mick Kipp, 51

Possessed of an uber hail-fellow-well-met personality, animated bartender presided over the proceedings at Camden Yards-area Pickles Pub for 25 years, sometimes while attired in pirate garb. On the side, he launched a company that made specialty rubs, salsas, and hot sauces devised from his own recipes.

Isabel Klots, 96

Widow of esteemed portrait/landscape/still-life painter Trafford Klots poured her energies into maintaining his artistic legacy after his 1976 death, including endowing the Maryland Institute College of Art’s annual summertime residency for artists at the couple’s chateau in Brittany, France.

Toni Linhart, 70

Austrian-born, soccer-style placekicker spent five-plus seasons with the city’s old NFL franchise, the Colts, helping lead the team to three consecutive AFC East titles in the 1970s and twice being selected to the Pro Bowl. Staying on here in retirement, he worked in community service.

Ann Miller, 97

City Health Department nurse founded and served as first executive director of the Maryland Food Bank, which coordinates donations of surplus items from retailers, wholesalers, and distributors to annually give nearly 450,000 pounds of food to 600 soup kitchens, pantries, and shelters statewide.

Steven Muller, 85

As president of The Johns Hopkins University and Hopkins Hospital in the 1970s and 1980s, he engineered the tremendous growth of both institutions—increasing operating budgets, overseeing a $400-million fundraising campaign—while burnishing their reputations nationally and internationally.

Lawrence “Larry” Simns Sr., 75

Led the Maryland Watermen’s Association from its 1973 inception until his death. In his negotiations with the state Department of Natural Resources, he constantly balanced the interests of his constituency with the need to protect the dwindling numbers of Chesapeake Bay fish, crabs, and oysters.

William Stump, 90

Longtime

Sun writer took over Baltimore magazine in 1964, beefing up its journalistic voice while positioning the monthly to eventually move from a Chamber of Commerce publication to complete independence. Finished out his career overseeing the now-defunct News American’s editorial page.

Gus Triandos, 82

Likable, lumbering, power-hitting catcher during the Orioles’ formative mid-to-late 1950s years was named an All-Star four times, and famously caught Hoyt Wilhelm’s 1-0 no-hitter win over the New York Yankees in 1958, the Orioles’ first, while providing the lone run with a seventh-inning homer.

John Wood, 80

City sanitation worker stockpiled residents’ discarded appliances——air conditioners, TVs, washing machines——and assorted detritus at his Northeast Baltimore home, often fixing them and giving them to needy neighbors. Those efforts, plus his help-everyone community spirit, inspired the 1990s television show

Roc.

Charlie Zill, 56

Armed with an orange fiddle and dressed in overalls and a straw hat, lanky Camden Yards usher rolled out his “Zillbilly” dance routine to the strains of John Denver’s “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” from the stadium’s upper deck during the seventh-inning stretch of Orioles home games.