News & Community

Saying Goodbye

We bid farewell to some of the notable Marylanders we lost in 2015.

Lloyd Fox/The Baltimore Sun

Marvin Mandel, 95

With Maryland Gov. Spiro Agnew decamping to the White House to serve as Richard Nixon’s vice president in January 1969, the General Assembly selected its Speaker of the House of Delegates, Marvin Mandel, to succeed him as the state’s chief executive. By then, Mandel had represented Baltimore City’s 5th District in the House since 1952, ascending through its hierarchy to become speaker in 1963. As governor, he used his familiarity with the ways and means of the state legislature to push through an ambitious agenda that efficiently condensed the executive branch’s nearly 250 agencies into 11 departments, revamped a byzantine state court system, set in motion the construction of Baltimore’s subway, and restricted possession of handguns. He easily retained the governorship in elections in 1970 and 1974.

But in 1975, Mandel was indicted by a federal grand jury for mail fraud and racketeering in connection with a scandal involving several friends who had surreptitiously bought a foundering Prince George’s County racetrack; two years later, he was convicted of accepting $350,000 from five associates in exchange for helping them obtain lucrative racing days at their newly acquired track. Sentenced to three years in prison, he served 19 months, and in 1987 saw his conviction overturned on a technicality.

“Without question, Marvin Mandel was the most accomplished and successful Maryland governor of the 20th century,” says Barry Rascovar, a veteran writer and commentator on state politics whose work regularly appears on MarylandReporter.com. “Yet there’s a permanent asterisk next to his name. It’s a complicated story—part Horatio Alger, part tragedy. Melodramas in his private life led to legally dubious deals with cronies who benefited from Mandel’s public actions. The bottom line: Despite his considerable flaws, Mandel’s political magic made Maryland a far better place for future generations.”

Courtesy of The News Literacy Project

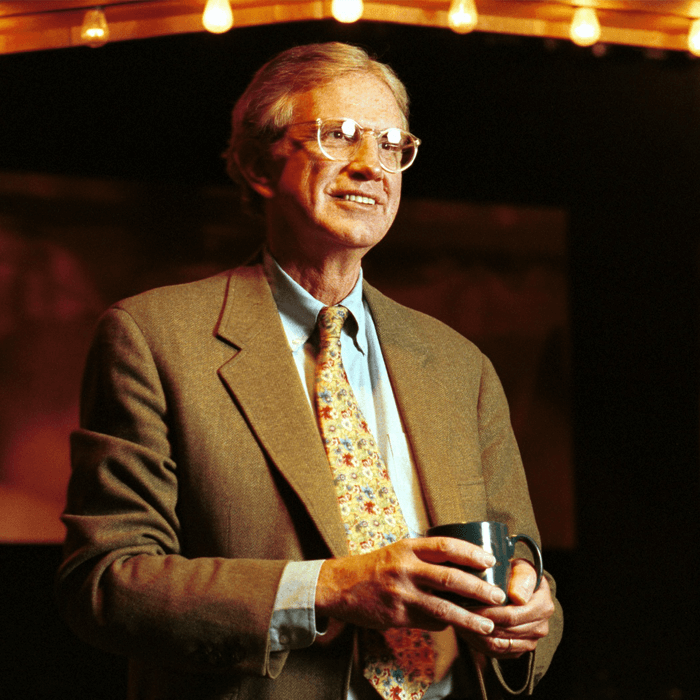

John S. Carroll, 73

By the time John Carroll returned to the city in 1991 to become the executive editor of The Baltimore Sun, he already had established his bona fides as a respected reporter and editor at dailies in Philadelphia, Lexington, KY, and, from 1966 to 1971, here with The Sun, covering the Vietnam War, Middle East, and White House. As editor, his embrace of investigative journalism and deliberately told features helped the newspaper win two Pulitzer Prizes. He moved on to guide The Los Angeles Times to even grander glories (13 Pulitzers) from 2000 to 2005, when, on principle, he resigned to protest management’s plan to slash newsroom staff.

“John ran The Sun during what we now see was a flush and fleeting era of cheeky ambition, and he had an uncanny ability to hear a curious fact and recognize that it might lead to a great story,” recalls Scott Shane, reporter at The Sun from 1983 to 2004, and in the Washington, D.C., bureau of The New York Times since then.

“He led with quiet enthusiasm. A colleague and I once had reported for nine months on a series explaining the National Security Agency. It was such slow going we thought he might fire us. Instead, he listened with his trademark deadpan expression and was silent for a minute before rendering his verdict: ‘Why don’t you go out there for a few more months,’ he said, ‘and see what you come up with?’”

Courtesy of The Baltimore Orioles

Hank Peters, 90

Hired as the Orioles’ general manager and executive vice president after the 1975 season, Hank Peters faced the daunting prospect of continuing the team’s long stretch of past successes: 12 out of 13 winning seasons since 1963 and World Series appearances in 1966 (a victory), 1969, 1970 (another victory), and 1971. Straight away, he oversaw a 10-player trade with the New York Yankees—adding catcher Rick Dempsey, as well as pitchers Scott McGregor and Tippy Martinez—that locked into place a well-balanced roster that would reel off 10 consecutive winning seasons, with trips to the World Series in 1979 and 1983, when the team beat the Philadelphia Phillies, the Orioles’ last world championship. Also under Peters’s stewardship, the team drafted and developed key players, notably pitchers Storm Davis and Mike Boddicker, plus Hall of Fame infielder Cal Ripken Jr.

Fired after losing seasons in 1986 and 1987, Peters went on to build the foundation of the Cleveland Indians’ powerhouse team of the mid- to late-1990s.

“In perhaps the greatest irony of Peters’ illustrious career as a baseball executive that spanned 30 years, his body of work in Baltimore was often overshadowed by his field manager, the fiery and pugnacious Earl Weaver, who contrasted drastically from his own low-key style,” notes Stan Charles, publisher of PressBox. “They were the ultimate fire-and-ice duo.

“I’ve never seen anyone more comfortable in his own skin. Peters knew who he was and was exceedingly clear on what his convictions were all about.”

Karl Merton Ferron, The Baltimore Sun

Frank M. Conaway Sr., 81

During his 18-year career in major-league baseball (1993 to 2011), outfielder Manny Ramirez’s curious on- and off-field antics often clouded his brilliance as a player: Manny loping to first base on infield grounders; Manny peeing against the left-field wall in Boston’s Fenway Park in the middle of a game; Manny shoving the Boston Red Sox’s 64-year-old traveling secretary. All this engendered a well-worn catchphrase: “Manny being Manny.”

Similarly, long-serving (1998 until his death) Baltimore City Circuit Court clerk Frank Conaway Sr.’s singular on- and off-the-job behavior sometimes obscured his dedication to the office: Conaway campaigning in 2010 on a three-wheeled electric scooter with bright yellow “Conaway” bumper stickers affixed across the top of his head and the front of his suit jacket; his comic 2011 public feud with blogger Adam Meister, including 70-something Conaway flashing a gun during a confrontation with Meister; his benign disruption of Sheila Dixon’s 2007 mayoral swearing-in ceremony. It was, political observers and voters alike knew, just “Frank being Frank.”

“He was a very colorful person,” admits Dixon, who grew up in the city’s Ashburton neighborhood, where he also lived. “He had a lot of energy and always looked at things positively. For all that he did within the courts, he was also very active in the community. People saw him as more than just the clerk of the court. They saw him as a stable individual who was committed to helping the community.”

Andre Chung/The Baltimore Sun

Peter W. Culman, 77

More than any single person, Peter Culman established Center Stage not only as the city’s foremost theater, but also as a regional playhouse renowned for presenting intrepid productions and, unusual in an era marked by precarious bottom lines for many cultural institutions, achieving financial solvency.

In his 33 years as Center Stage’s managing director, he oversaw its recovery from a crippling financial crisis, its survival after a devastating 1974 fire leveled its original home, its relocation the following year to a more suitable venue, its accumulation of an enviable endowment, and its dramatic increase in annual budget, all before retiring in 2000.

“At a theater company, the only top name that audiences usually know is the artistic director,” notes J. Wynn Rousuck, theater critic for The Baltimore Sun from 1984 to 2007, and in the same post at WYPR ever since. “It’s the same with most orchestras or even sports teams— you know the conductor, you know the coach, but you may not know the chief administrator. In many ways, however, Peter Culman was the public face of Center Stage.

“Quirky, courtly, and indefatigable, he played a behind-the-scenes role, but without him those scenes never would have made it to the stage.”

Blaze Starr, 83

Part performance artist, part exhibitionist, Blaze Starr somehow dignified stripping, reigning as the nation’s Queen of Burlesque from the mid-1950s until well into the 1970s. Va-va-va-voom in all aspects—striking red hair, bounteous bust, and a saucy, mischievous attitude—she wowed audiences in nightclubs across the U.S., operating out of her home base, the 2 O’Clock Club on The Block. Along the way, she indulged in numerous affairs, most infamously with Louisiana’s married governor, Earl Long, a relationship chronicled in the 1989 film Blaze starring Lolita Davidovich as Starr and Paul Newman as Long.

Off-runway, she showed savvy as a businesswoman (owning/managing the 2 O’Clock Club) and creativity as a designer (making her own costumes and producing jewelry that she sold commercially). And when she felt that stripping had devolved into gratuitous raunch, she retired her G-string, her pasties, and her act.

“People say burlesque died in the 1970s, but with her ladylike style, knack for show, and air of glamour, Blaze Starr kept the embers smoldering on a Block that had mostly yielded to nudity and pornography,” says Margo Christie, an ex-Block stripper and author of These Days: A Tale of Nostalgia on a Burlesque Strip. “Throughout the ’80s, several clubs featured at least one dancer who stripped with gloves, stockings, and feather boas. Indeed, it can be said that, thanks to Blaze, the seeds of the late-1990s burlesque revival movement were planted and nurtured right here in Baltimore.”

Courtesy of Rachel Rock Photography

Thomas Palermo, 41

Tom Palermo’s hit-and-run death while biking on Roland Avenue in the waning days of 2014 shocked not only the local cycling community but everyone in the area, especially when the driver was found to be a bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland who was driving while drinking and texting on her mobile phone at the time of the accident. Ten months later, she was sentenced to seven years in prison after pleading guilty to vehicular manslaughter and related charges.

A senior software engineer at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Palermo also had established a reputation as a meticulous builder of custom steel bicycle frames.

“A devout family man and cyclist, Tom was in his element when sharing his passion for cycling,” says Gary Dunn, an adventure guide who rode with Palermo and whose company, Alpine Inspirations, takes people climbing, caving, and mountain biking. “His handcrafted bicycle frames were rideable works of art. Tom loved to talk with anyone about bicycles. It didn’t matter what you rode or how long you had ridden, as long as you were riding.

“Tom was also passionate about trying to create a better world for those around him: city planning, bicycle routes, the list goes on. He was a quiet leader reading through master plans and submitting ideas.”

Colby Ware/The Baltimore Sun

Carole Sibel, 79

When it came to channeling her high-octane fundraising energies, Carole Sibel took a democratic approach, eschewing pet projects or single issues to spread her charitable tentacles to nearly every conceivable facet of civic life: education, medicine, the arts, animals, the Jewish community, the homeless, and victims of sexual assault. She embodied diversity. And her Energizer Bunny philanthropic activities were done not in search of social plaudits but, rather, for the sheer love of helping others.

“Carole Sibel left an astounding legacy of generosity,” says Donald Hutchinson, president and CEO of the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore, on whose board Sibel served when she died. “With over three decades in leadership roles at the zoo, the Baltimore School for the Arts, The Associated: Jewish Community Federation of Baltimore, and the Mount Washington Pediatric Hospital, the list of causes she championed goes on and on. Carole worked tirelessly as an effective philanthropist, but, more than anything, she was a great woman with a wonderful family, wide circle of friends, sense of humor, and big heart.”

Courtesy of The Johns Hopkins Hospital

Dr. Levi Watkins, 70

As an 8-year-old growing up in Montgomery, AL, Levi Watkins met Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the pastor at the church that Watkins’s family attended. Later, he participated in the landmark, King-led 1955 Montgomery bus boycott and served as a volunteer part-time driver for the civil-rights leader.

Subsequently, Watkins shattered the color barrier as the first black student to attend and graduate from the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, before embarking on a groundbreaking career at Johns Hopkins—initially as one of its School of Medicine’s first black interns, then as Hopkins Hospital’s first black chief cardiac surgery resident, and, finally, as an innovative heart surgeon. Among his numerous achievements, he was the first to successfully implant an automatic heart defibrillator—a device that senses and then corrects a person’s arrhythmia—in a human patient. And throughout his 40 years at Hopkins, he helped to significantly increase admission of African-American students to the medical school.

“He was a great heart surgeon, but, beyond that, Levi Watkins transcended cardiac surgery and even all of medicine because of a supreme passion to see that the dream of the civil-rights era—freedom, equality, dignity, and opportunity—did not die,” says Dr. David G. Nichols, president and CEO of the American Board of Pediatrics, and, formerly, a long-time colleague of Watkins’s at Hopkins. “He brought that passion to every person he met, whether it was a brand new student or an intern or a world leader. There was no one quite like him.”

J. Pat Carter/The Baltimore Sun

William “Bill” Swisher, 82

In the early 1970s, the city reeled from a burgeoning murder rate and 1973’s sensational execution-style killing of James “Turk” Scott, a House of Delegates member and alleged drug dealer. Campaigning in the 1974 Democratic primary on a law-and-order theme, Bill Swisher, a former assistant state’s attorney, narrowly defeated Baltimore state’s attorney Milton B. Allen (the first African-American elected to citywide office outside a judge), with one of Swisher’s ads comparing the city to “a jungle.” He then breezed to victory in the general election—and won again in 1978. But a 1979 trial for political corruption, in which Swisher was acquitted, nonetheless tainted his reputation, and he lost the 1982 primary in a landslide to Kurt Schmoke. “In his eight years in office, he came across as somewhat introverted, brusque, and shy,” remembers David Blumberg, the chairman of the Maryland Parole Commission. “His 1974 characterization of the city as ‘a jungle’ was seen as a poor choice of words, but it got people’s attention. Voters obviously believed he had done a good job, because he won with virtually no opposition four years later.”

Courtesy of Twitter

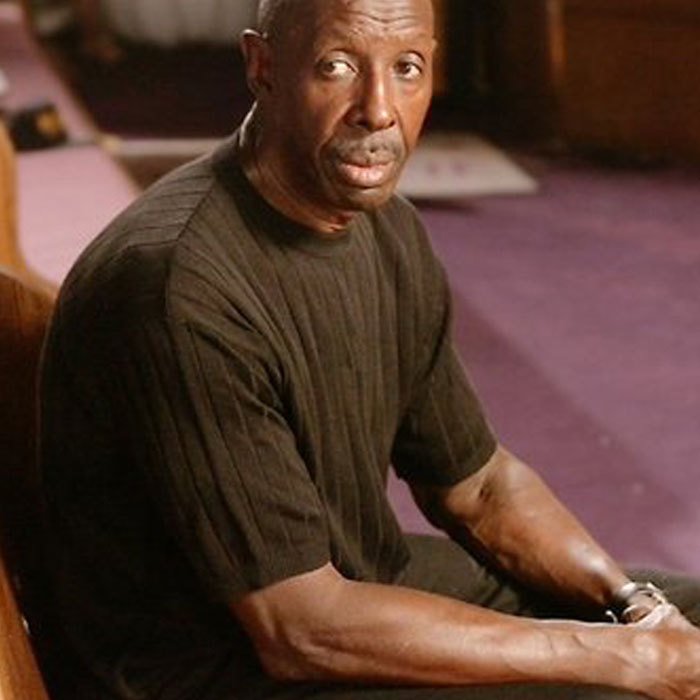

Melvin Williams, 73

"Little" Melvin Williams' decades-long arc from resourceful drug-dealing sinner to civic-minded saint traced a course from West Baltimore's beleagured Pennsylvania Ave. in the 1960s, where Williams' cocaine- and heroin-selling empire accounted for, by his estimate, some $1 billion, to a got-religion mentor preaching the gospel of responsibility to young black men still locked into "the game" in the 2000s. Along the way, he was convicted four times on weapons and drug charges, spending more than 20 years in prison, where he experienced a spiritual awakening, finally emerging in 2003.

In the mid-1980s, while still imprisoned, Williams gave several interviews to then-Baltimore Sun reporter David Simon for the latter's illuminating series on West Baltimore's drug trade, later reconnecting when Simon cast Williams as Deacon, a stabilizing neighborhood force, in his HBO series The Wire.

"Little Melvin ran the streets like a track star, creating an empire and an honorable legacy by using nothing but the scraps that systemic racism dumps into the black community," says D. Watkins, a Salon columnist and author of The Beast Side: Living (and Dying) While Black in America. "It wouldn't be far-fetched to assume that he could've easily run a Fortune 500 company in his sleep if society played fair; however, we all know it doesn't. Melvin was incarcerated: He took his time like a man, saw the error of his ways, and then spent the rest of his life working to keep young men like me from making the same mistakes. As a kid, I looked up to Little Melvin because of his money-making skills; as a man, I honor his community work and commitment to change."

Caleb Bratayley, 13 Born Caleb LeBlanc, he and his two sisters became social-media phenoms as the stars of his family’s “Bratayleys” YouTube vlog (video blog), their quotidian lives regularly paraded before 1.7 million eager subscribers. He died of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a heart disease.

Lou Cedrone, 92 Venerable Evening Sun film critic eschewed auteur theory and other modernist constructs in favor of an everyman approach to the movies that emphasized plot and acting, an unfussy tactic that resonated with readers for nearly 30 years.

Louis Chiapparelli, 90 Jovial maitre d’hotel at his family’s popular Little Italy restaurant deftly managed hordes of diners, keeping the front of the house humming efficiently; along with his three brothers, he also significantly expanded the premises.

Johnny Clinton, 73 Pimlico community leader’s Park Heights Avenue barbershop served as an informal salon for a bevy of his local politician clients (Kurt Schmoke, Kweisi Mfume), where public affairs—neighborhood, municipal, national—were avidly discussed and elected officials assessed.

Sam Culotta, 91 Luckless Republican standard-bearer in a city awash in blue voters represented his party in six Baltimore mayoral elections between 1963 and 1991, losing on each occasion, including twice against the seemingly invincible William Donald Schaefer.

Walter R. Dean Jr., 80 Respected civil-rights activist participated in landmark 1950s and ’60s demonstrations against segregation in the city, later serving in the state’s House of Delegates from 1970 to 1982 and as chairman of Baltimore City Community College’s Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Robert “Robbie” Goldman, 98 Guru of the local legal fraternity served as managing partner of Frank, Bernstein, Conaway, and Goldman from 1966 to 1983, honing a reputation for perspicacity in corporate, business, and, especially, real estate law, while mentoring many younger attorneys.

Gerald Gross, 94 Thirty-year publishing executive and editor shepherded into print Nazi architect/minister of armaments Albert Speer’s two best-selling memoirs, as well as National Book Award-winning works by novelist Wright Morris and poet Richard Wilbur, among other literary luminaries.

James Hardesty, 68 Keen stock market analyst, investment strategist, and portfolio steward rose through the ranks at Mercantile-Safe Deposit and Trust before co-founding Hardesty Capital Management in 1995, which, under his leadership, eventually oversaw close to $1 billion in assets.

Robert Harvey, 94 Adroitly guided the old Maryland Trust Co. through multiple mergers with local and state banks throughout the 1960s and 1970s to produce Maryland National Bank, assuming CEO and chairman roles of a regional financial behemoth boasting a network of 140 branches.

Robert Hiller, 93 Tireless fundraiser and organizer for local nonprofits, notably The Associated—the umbrella group for various Jewish philanthropies—and the Krieger Fund, which funnels financing to multiple Baltimore social projects. Also worked on behalf of the National Council on Soviet Jewry.

Dr. Howard W. Jones Jr., 104 Forever altered human reproduction when, together with his wife, Dr. Georgeanna Seegar Jones, he successfully induced the nation’s first in vitro fertilization baby in 1981. Earlier, at Johns Hopkins, he established the U.S.’s first hospital-based sex-change clinic.

Junetta Jones, 78 African-American soprano who, after graduating from the Peabody Conservatory, won the Metropolitan Opera’s 1963 young artists competition and then performed with the famed company and throughout Europe before organizing musical performances at Artscape.

Dr. James Jude, 87 As a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine resident in the 1950s, he pioneered using external, manual pressure to restore normal heart function to patients in cardiac arrest, a technique that he helped develop into cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), which he championed nationwide.

Maravene Loeschke, 68 Esteemed educator assumed the presidency of Towson University in 2012 after spending three decades at the institution where she earned her undergraduate degree, chaired the theater arts department, and served as dean of the College of Fine Arts and Communication.

Morton J. “Morty” Macks, 90 His family-owned Chesapeake Realty Partners developed huge swaths of Baltimore’s suburbs in the decades after World War II, primarily using the new process of prefabricated housing components, and then went on to construct numerous apartment complexes and shopping centers.

Decatur H. “Deke” Miller III, 82 Former chairman and managing partner of Piper & Marbury excelled at corporate law, while his exhaustive civic engagement included leadership posts with the BSO, Enoch Pratt Free Library, Greater Baltimore Committee, College Bound Foundation, and The Walters Art Museum.

Dr. Keiffer Mitchell Sr., 73 A gastroenterologist, the son of prominent civil-rights pioneers Clarence Mitchell Jr. and Juanita Jackson Mitchell broke the color barrier at Gwynns Falls Junior High and later opened his practice in the economically challenged West Baltimore community of Upton.

Dr. Vernon B. Mountcastle, 96 Johns Hopkins physiologist’s groundbreaking research in the 1950s determined how the brain organized itself to process information and function, providing the crucial map that led to key developments in modern neuroscience.

Marion A. “Mugs” Mugavero, 92 Irascible owner-operator of legendary Little Italy bodega/restaurant Mugavero Confectionery, which, from the late 1940s until the 2000s, functioned as a neighborhood hangout and ad-hoc eatery serving no-nonsense fare (meatball subs) and selling everyday essentials.

Jim Mutscheller, 85 Bruising tight end for the Colts caught a six-yard pass to set up fullback Alan Ameche’s one-yard touchdown surge (behind Mutscheller’s block) to win the 1958 NFL championship game in overtime against the New York Giants, famously known as “the greatest game ever played.”

Dr. Richard Ross, 91 Distinguished Johns Hopkins cardiologist presided over the School of Medicine as dean from 1975 to 1990, dramatically expanding research facilities and curriculum. One of three physicians chosen to examine recently resigned President Richard Nixon to determine if he was healthy enough to testify in the Watergate hearings.

Dr. Elijah Saunders, 80 A University of Maryland School of Medicine cardiologist—the state’s first African-American in the field—he led the effort to discontinue racially segregated wards at the UM Medical Center and performed important research into the role of hypertension in the cardiovascular health of African-Americans.

Zvi Shoubin, 86 Career TV exec created popular afternoon teen dance-party program The Buddy Deane Show in 1957—the template for John Waters’s film/Broadway production Hairspray—before working in various roles at TV stations all over the U.S., including at MPT from 1996 until his death.

William “Bill” Toohey, 69 Former radio newsman served as the calm and collected public spokesman for the Baltimore County Police Department from 1996 to 2010, most memorably in 2000 during the two-week reign of terror by Joseph Palczynski (four murdered, three others taken hostage).