News & Community

Fading History: “Ghost” Signs Evoke Baltimore’s Commercial Past

Over the past 20 years, Lashelle Bynum estimates she's found and photographed close to 200 ghost signs throughout the city.

“The first one that caught my eye, and I didn’t know it was the only African-American one in Baltimore, was Lenny’s House of Natural in Poppleton,” recalls Lashelle Bynum, flipping through her photography collection of fading “ghost signs” which adorn many older and often neglected buildings in the city. “I knew that’s where Oprah got her hair done when she was here,” says the 63-year-old recently retired state administrative specialist.

Lenny Clay, owner of Lenny’s House of Natural, and once dubbed the “Mayor of Poppleton” by former Mayor Kurt Schmoke, also cropped the hair of Baltimore’s leading Black sports figures, preachers, and politicians, including former Bullets star Earl “the Pearl” Monroe, Rev. Vernon Dobson, and former Congressman Elijah Cummings.

“It was the nostalgia,” says Bynum of her instinct to shoot the building. “I thought it was fascinating. And then I interviewed Lenny about the history of the shop and found out that, actually, the sign was put up for a movie, The Meteor Man, they were shooting in the neighborhood. But that was the catalyst.”

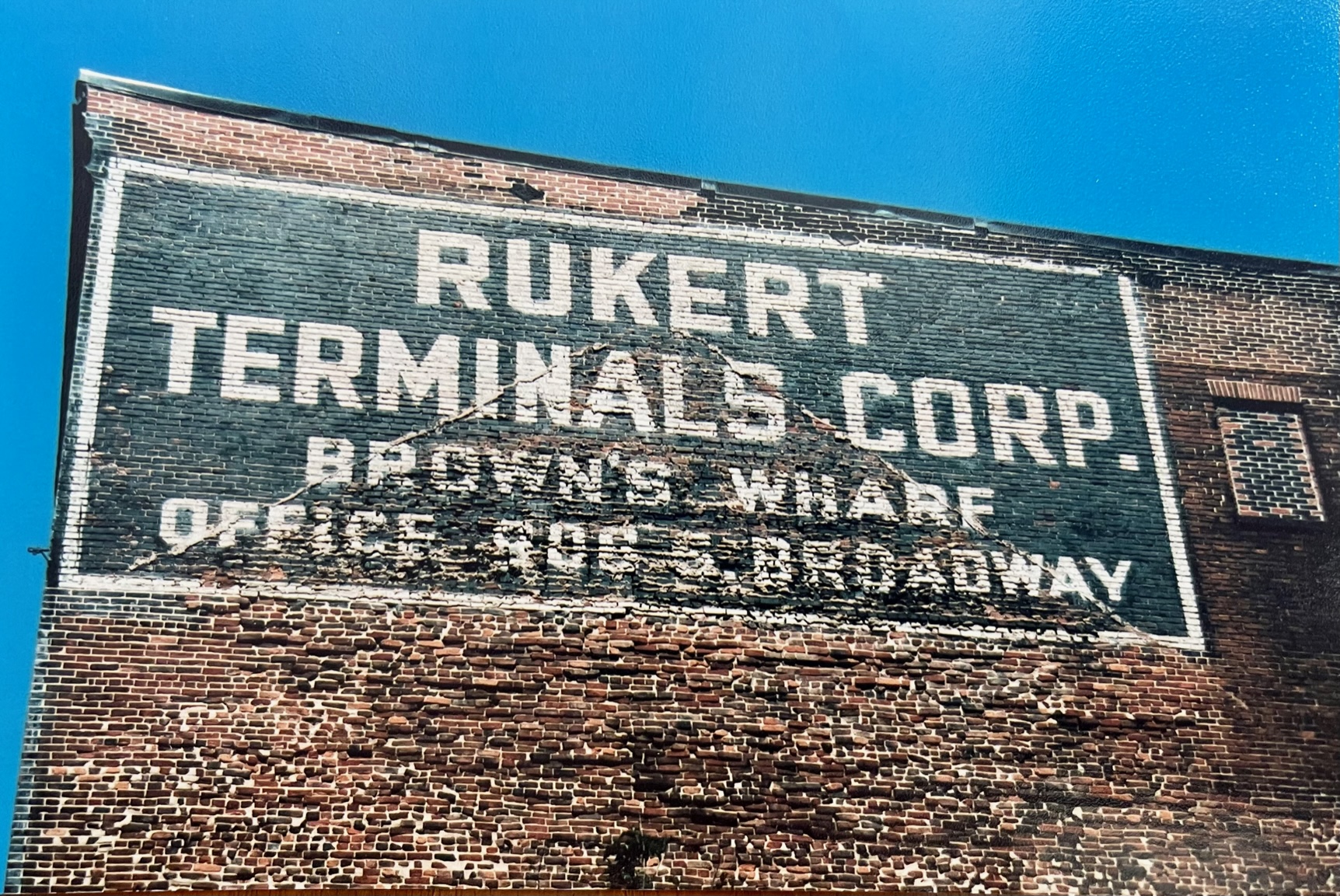

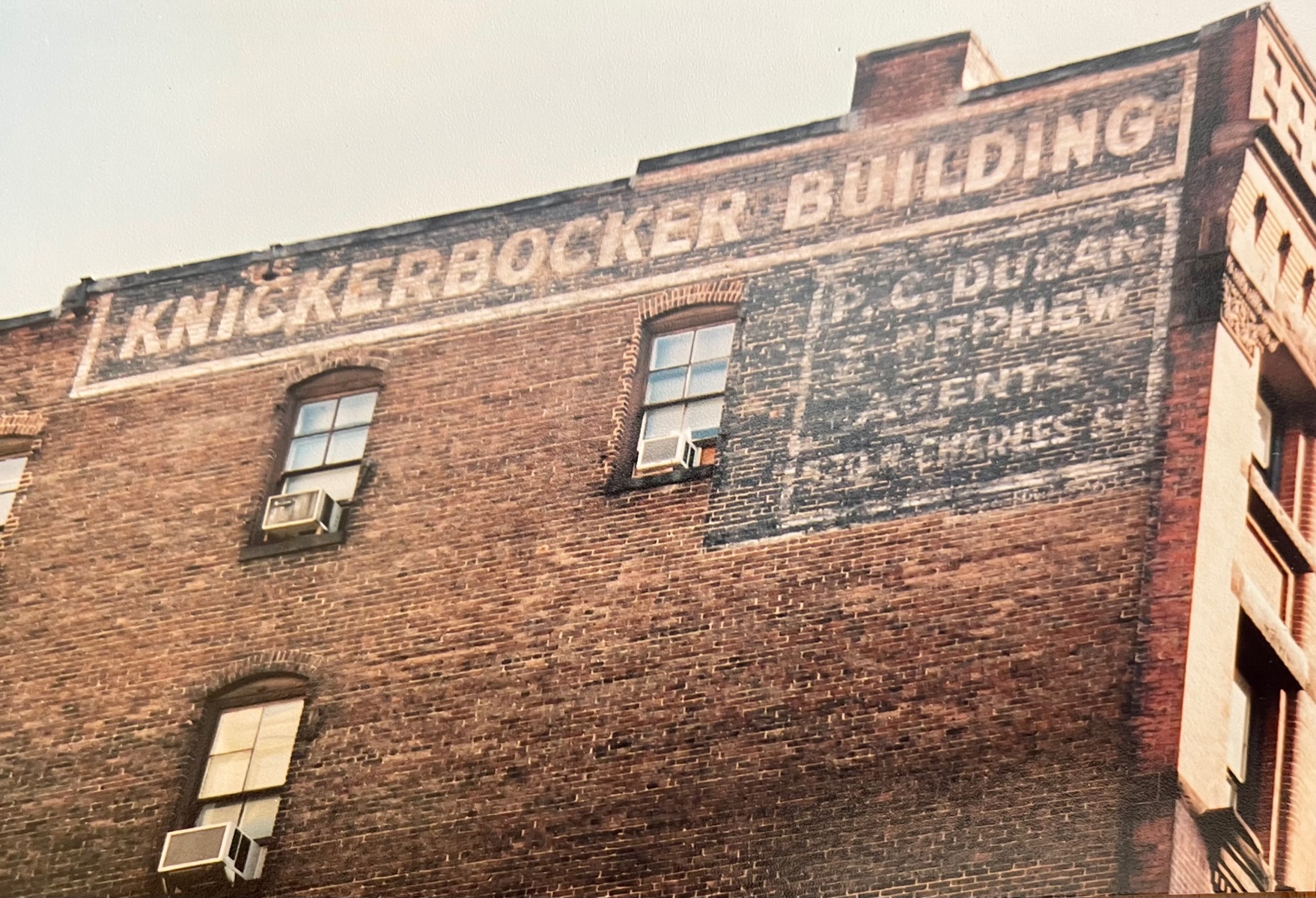

Over the past 20 years, Bynum estimates she has found and photographed close to 200 local ghost signs. Or as she describes it, they’ve found her. Most of the mural-sized painted signs she’s shot—outside of a handful that were repainted as part of renovation projects, like the Cloud Mattress advertisement along I-83 or the BAGBY FURNITURE CO. lettering in Harbor East—are decades older than the retro advert outside the former location of Lenny’s.

According to Bynum’s research, five companies—Globe, Park, Chevery, Prichett, and Morgan—produced the bulk of the colorful and larger-than-life signs, which date back to Depression-era Baltimore. In fact, the most famous ghost sign in Baltimore is the faded, blocked-lettered VOTE AGAINST PROHIBITION at the intersection off South Broadway in that historical hotbed of hooch, Fells Point. Coincidentally, not far away, just up Central Avenue, one of the more visible ghost signs advertises the services of JOSEPH KAVANAGH CO. PRACTICAL COPPERSMITH, a family-run operation that began designing and building distilling equipment in 1866, and then turned to bootlegging during Prohibition.

Nicknamed “wall dogs” back in the day, the craftsmen who created the signs were skilled artists who worked from scaled drawings—not unlike today’s public artists—and whose biggest challenge was making sure the lettering appeared level even when the wall was not. Some would tote perforated paper outlines up the scaffolding with them, using chalk or powdered charcoal to create a series of dots that they could then connect with paint, which was mixed with linseed oil, varnish, and occasionally gasoline.

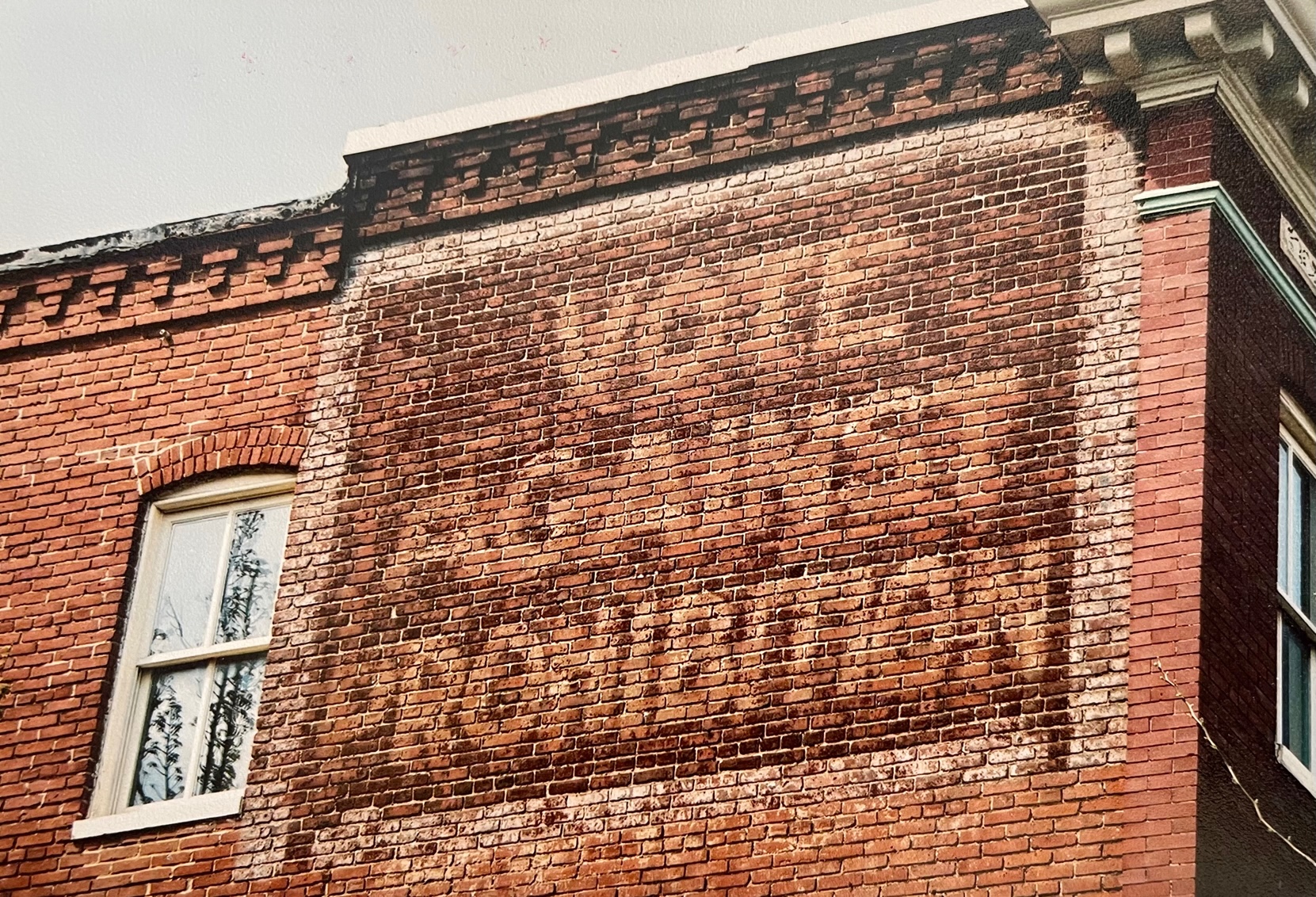

Generally, it took only a few hours to dry and, depending on exposure to the sun, some held up longer than others. Because of its high asbestos content, white paint tended to deteriorate more slowly. It also seems more noticeable after a rain, which is how the moniker “ghost” sign arose.

Although she has no formal training as a photographer, Bynum has been interested in the city’s urban landscape, architecture, and the visual arts as long as she can remember, going back to collaging as a young girl at her mother’s dining room table in Edmondson Village. In recent years, she’s exhibited her photographs of Baltimore’s fading signs at the Enoch Pratt Free Library downtown, the Eubie Blake Cultural Center, and the Arena Players theater.

Previously a volunteer and now a board member at Baltimore Heritage, she also presented to the Baltimore Architecture Foundation in March. The first photograph of a ghost sign that she sold was of the well-preserved vertical ad for K&L DRY GIN—tagline “BUY WITH CONFIDENCE”—near Hanover and West Ostend streets in South Baltimore.

The most vivid ghost sign in the city, however, is pictured with Bynum above, advertising both CUBANOLA 5¢ CIGARS and N. FAULSTICH CARRIAGE & WAGON BUILDER at East Fayette and Duncan streets. That sign had remained hidden for decades, and thus out of the sun, before it was rediscovered five years ago after a rusty section of metal siding fell off the vacant building. Over its various iterations, the building had served as the home of a carriage and wagon maker, a furniture warehouse, and, finally, a Pentecostal church.

“I don’t know why I am so fascinated with them exactly,” says Bynum, who hopes to pull her photographs and research into a coffee-table book. “It’s not something I can put into words, other than it gives me a feeling of a simpler time.”

She thinks about it some more and says she appreciates the moment of discovery of a ghost sign, a kind of merging of the past and present when time seems to momentarily stop. Today, she says, a lot of people drive everywhere or walk around “looking at their smart phones, barely noticing the world around them.”