News & Community

Coming Home

The former U.S. Ambassador to Syria returns home and reflects on three decades in the Middle East.

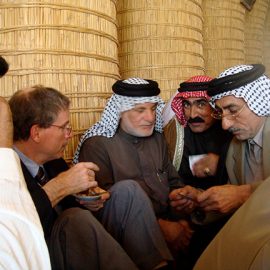

In December of 2010, a Tunisian street vendor’s self-immolation kick-started an unforeseen Arab Spring, sending anti-authoritarian protests sweeping across Yemen, Egypt, Algeria, and Jordan. A month later, Robert Ford, the new U.S. Ambassador to Syria—the first in more than five years—arrived in Damascus amid a sudden, coalescing protest movement against the government of President Bashar al-Assad. As the Syrian uprising grew stronger that spring and summer and Assad ratcheted up the government’s response, Ford, by all accounts, made a bold decision to leave the safety of the embassy, driving 217 kilometers to Hama, a city of almost 1 million people, to witness firsthand the massive anti-government rallies there.

“There were stories that the government was sending in the army and potentially we were going to have this situation where you have soldiers shooting at tens of thousands of protestors,” recalls Ford, sitting in his Bolton Hill living room three years later. “I mean, we [the United States] are trying to defend the right to protest peacefully. At least if I am there and the Syrian government says, ‘Oh, the protestors started the violence’—well, maybe they did, maybe they didn’t—but we’d be able to report what we saw.”

Traveling in an SUV with a Defense Department attaché, an operations officer, and his bodyguard (the French ambassador was also on the trip, but in another vehicle), Ford was surprised the group was allowed through army checkpoints. Upon reaching Hama and looking for central Assi Square, since renamed Martyrs’ Square, there was a second surprise: No one had brought a map. “This hasn’t been reported, and I don’t get care if it gets into print, but we were just trying to find a place to park a few blocks away where we could go into a building and watch the square,” Ford laughs. “And they don’t have GPS in Syria—it’s illegal—so we constantly had to stop and ask for directions.” Word got around that the U.S. ambassador was in town, and their vehicle was recognized the following day, with protestors surrounding the SUV and chanting, “The people want the regime to fall!” Ford says his bodyguard was certain they were going to be attacked. Instead, the protestors placed flowers and olive branches on the hood and windshield—a surreal scene captured in a YouTube video. “My bodyguard went nuts, but I told him, ‘Relax, they’re not against us, they’re against the government. They’re happy we’re here.’” Three days later, however, back at the U.S. Embassy, the story took a dark turn.

Ford’s appearance in the middle of the anti-government demonstration—accidental or not—and a subsequent Facebook post, in which he stood up for the protestors’s right to peacefully assemble, had upset the Assad regime. They accused him of interfering in domestic politics, and, soon enough, a pro-government group swarmed the embassy, hurling rocks through windows and scaling the compound’s wall. Ultimately, a single iron door separated Ford and embassy personnel from those banging to get into the main building’s inner sanctum.

“Thank God the door held, it took three hours for the Syrian police to come and disperse the crowd,” Ford says. “I had Marines with rifles loaded, cocked and ready, on either side of me—maybe a dozen feet from the door. And they said, ‘If they get through, we are going to shoot.’ I told them that they couldn’t shoot unless the mob rushed the embassy staff. I had to say that to 21-year-old Marines. It was the scariest thing I ever had to go through.”

“If you have to feel totally safe, you’re basically useless in those jobs.”

Not long afterward, Ford, who continued to meet with opposition and government leaders despite near-constant harassment, was called back to the United States because of threats against his life, and the embassy was shuttered.

“Different ambassadors have different styles,” says Mounir Ibrahim, a State Department Foreign Service officer who worked closely with Ford in Syria. “Some work at appeasing whoever they think they need to in Washington, repeatedly polishing their reports. But Ambassador Ford has always been about making the human connection, which is the essence of what a diplomat should be doing.”

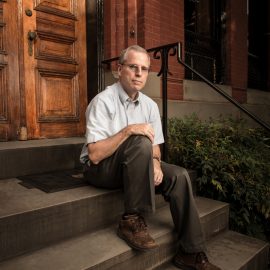

Back in Baltimore and pleased to be teaching this fall at The Johns Hopkins University, the polite, naturally soft-spoken, casually dressed Ford—Dockers-style slacks, open-collar shirt, and comfortable shoes—could easily pass for the most innocuous of neighbors on his leafy, close-knit block of Victorian townhomes. He remains an avid Orioles fan since his own undergraduate days at Hopkins (he was raised in Denver), and is one of the neighborhood’s stalwart early-morning joggers. He appears so much a regular Joe, in fact, that security personnel from House of Cards—the TV show is filmed a few doors up—often fail to recognize the actual Washington insider in their midst, and try to prevent him from getting too close to the shoot as he returns home from his pre-dawn runs. Earlier this year, the 56-year-old retired after three decades with the State Department, where his wife, fellow diplomat Alison Barkley, remains. He left as one of the country’s most experienced, likeable, and trusted hands in Middle-Eastern diplomacy, but not without some controversy, which we will get to later.

In 2012, Ford was awarded a Profile in Courage Award by the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for his work in Syria and his shows of solidarity with the pro-democracy movement there, which included attending the funeral of an opposition activist.

“He spent his entire career in dangerous places, including serving as Ambassador to Algeria for two years between stints in Iraq—and he’s been a brilliant reporter all that time, as he was in Syria,” says former U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan Ronald E. Neumann, noting that before Ambassador Christopher Stevens’s tragic death in Libya in 2012, three U.S. ambassadors were killed in the Middle East in the 1970s. “He’s not someone who stays in [the embassy], but someone who gets out and develops a very broad range of contacts. If you constantly have to feel totally safe, you’re basically useless in those jobs.”

A self-proclaimed history nerd growing up in an upper-class community, Ford studied European and American history as well as French and German at Hopkins—he speaks five languages today—and smiles when asked how he became interested in the Middle East. “Lawrence of Arabia,” he says, admitting, unabashedly, that he was completely taken by Peter O’Toole’s portrayal and the exoticism of the film. “I saw it in college, and it had a huge impact on me.” Soon after, before his senior year, he signed up for a summer Arabic program at Georgetown University. This was 1979, the year of the Iranian Islamic Revolution, when Ford was driving his beloved 302 V8 Mustang—“a white shark,” he calls it—between Denver, Baltimore, and Washington, regularly finding himself in gas lines. “I remember thinking, ‘Man, I really do need to study Arabic—these guys are taking over the world,’” Ford says. “I didn’t even know,” he chuckles, “that Iranians aren’t Arabs.”

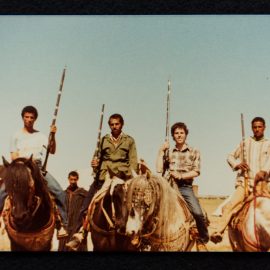

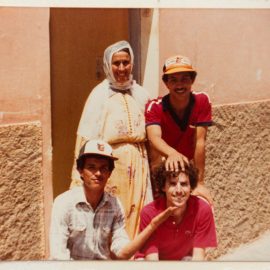

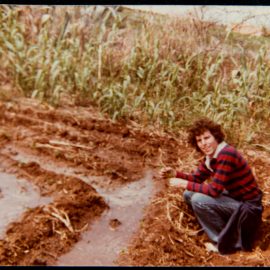

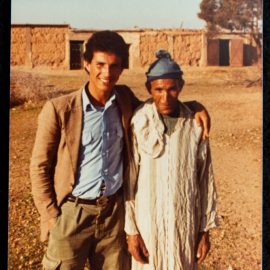

After earning his master’s degree from the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, Ford also realized he wasn’t getting far with his Arabic here. He joined the Peace Corps, with a Foreign Service career in mind, and got sent to Morocco. He’d had it in his head that he was going to a rich emirate like Kuwait or Qatar, but when he got to his post, it proved just the opposite. “Dirt poor, kids with running noses and bare feet, and people riding donkeys,” he says. “I taught in a school in a little town between Marrakesh and Casablanca without glass on the windows and was shocked by it all at first. I had to be informed by another volunteer that the Peace Corps only sends people to poor countries—that’s how naïve I was.” Today, things are different, of course, and if there’s any doubt of Ford’s lasting affection for the Middle East—or Baltimore—at home he still proudly displays photos from that time of himself alongside Moroccan village teenagers in black and orange O’s caps.

“I met with Assad twice, and I can tell you that he can be a very charming guy.”

Currently, he’s a Middle East Institute senior fellow in Washington and in demand as a speaker on Arab issues, but he intends to turn his attention more toward Baltimore. He already serves on the Mount Royal Improvement Association’s board and has an eye toward volunteering with an organization such as Baltimore Heritage or the Baltimore City Historical Society, having developed an appreciation for architecture while working near 1,000-year-old mosques.

When Ford retired in February, he did so—as he usually does, the adventure to Hama notwithstanding—with little fanfare. There had been talk that Secretary of State John Kerry wanted him as the next Ambassador to Egypt. But, in truth, a frustrated Ford had already decided to leave the State Department. Although he didn’t say so at the time, he’d come to the difficult conclusion that he could not continue to defend the Obama Administration’s then largely hands-off policy toward Syria. State Department officials, much like the military, are charged with serving whomever is sitting in the Oval Office, whatever the political or policy disagreements. But Ford finally felt he could no longer maintain his personal integrity and support the administration, which was refusing to fund, train, or arm the Free Syrian Army, the main opposition to the Assad regime.

This June, Ford penned a controversial op-ed to The New York Times, making the case that the failure to fully support the Free Syrian Army had allowed Assad to remain in power and created a vacuum in parts of Syria for “Al Qaeda offshoots,” notably the Islamic State, to step into the fray. The piece got wide play and created a stir in foreign policy circles and the national media. And, in fact, three months later, Congress would approve President Obama’s eventual request for just such military aid and training—albeit after the beheadings of two American journalists apparently convinced the White House they could no longer stay on the sidelines. The quiet diplomat, actually receiving news of the Senate vote via text during this interview, raised his arms and allowed himself a brief, “Hooray.” Inside the State Department, he’d been pushing for similar action for two years.

“You know, what we wanted to do is get to a political settlement in Syria with Assad gone—and we still do. Secretary Kerry said that [recently] in a Senate Foreign Relations Committee,” Ford says, explaining his position. “I met with Assad twice, and I can tell you that he can be a very charming and suave guy. If he wasn’t the Syrian president, you’d like to sit next to him at a dinner party. But we are dealing with a very tough group of guys in Damascus. They are not nice people and won’t make any concession at a negotiating table if they don’t have to, which is why I was saying we have to put more pressure on the regime on the ground.” The Syrian opposition needs ammunition, military equipment, and cash for their families to buy food, Ford continues. If they don’t get it from the moderate groups, “they are going to get what they need to fight Assad from the extremist groups, who are well-funded.”

In the broader picture, Ford says, some Middle Eastern countries may simply not yet possess the democratic values associated with the West. However, context is important, he notes, adding that his grandmother did not have the right to vote in the U.S. when she came of age. But he emphasizes that people in Middle Eastern countries do very much want to be treated with dignity by their governments, and that they are sick of the petty corruption, of paying bribes to officials and to police so they don’t get arrested and beaten up for not doing anything in the first place. “That video that came out today,” Ford says, referencing surveillance footage of a Baltimore City police officer beating up a citizen outside a Greenmount Avenue liquor store, “that happens multiple times a day in a police station in an Arab country, and people are sick of it.”

He acknowledges the reactionary oppression and ongoing violence in the Middle East, what some now call the Arab Winter, and mentions that PBS host Charlie Rose recently asked if he has become pessimistic about the region’s future. Ford says that he hasn’t given up hope for greater liberty and human rights.

“The situation in Tunisia has actually been pretty peaceful,” he says, adding the country is moving toward new elections as well. “In Iraq, though not an Arab Spring country, there’s been an election and they have a new government and a new prime minister, and that’s positive.”

We have to see how things turn out in places like Egypt and Yemen, he admits.

“It’s going to be a bumpy ride, but I think—and this is where I am going to sound like Francis Fukuyama, who wrote The End of History after the Berlin Wall came down and Soviet Union collapsed—that we haven’t reached the end of history in the Middle East,” Ford says. “I guess that’s how I’d say it.”