In their opening statement late Wednesday morning, Baltimore prosecutors alleged Ofc. William Porter was “grossly indifferent” and “criminally negligent for failing to do his legal duty when he had the duty and obligation to help” Freddie Gray when the 25-year-old Gray requested and needed medical attention.

In their opening statement Wednesday afternoon, defense attorneys for Porter described the officer as well-intentioned, but inexperienced and ill-served by misguided police department practices and inept communication methods.

Also in dispute was the timeline of Gray’s ultimately fatal spinal cord injury.

Baltimore City Chief Deputy State’s Attorney Michael Schatzow told the jury that Porter was present at five of the six stops that the police transport van made with Gray, and that by the fourth stop, Gray’s deadly injury had occurred and his condition was worsening. Schatzow said that Gray had requested medical attention, said he couldn’t breathe, and his pleas for help were ignored.

Schatzow also noted that Gray was never secured into the police transport van with a seatbelt—per department rules.

“There was no reason not to put him in a seatbelt unless he [Porter] didn’t care,” Mr. Schatzow said.

Defense attorney Gary Proctor told the jury that Porter did not believe that Gray was injured at the fourth stop, but had been feigning injury in hopes of being taken to the hospital instead of jail. Proctor added it was not Porter who initially arrested Gray and therefore not his responsibility, or not his responsibility alone, to properly secure Gray. Proctor described Porter as a caring young man, who sought to serve his community as a police officer after being rejected for military service because of colorblindness.

While Gray’s death is tragic, Proctor said, “so is charging someone who did not precipitate it.”

Proctor concluded his opening statement by turning a rallying cry used by activists protesting police brutality issues on its head. He told jurors: “Let’s show Baltimore the whole damn system is not guilty as hell.”

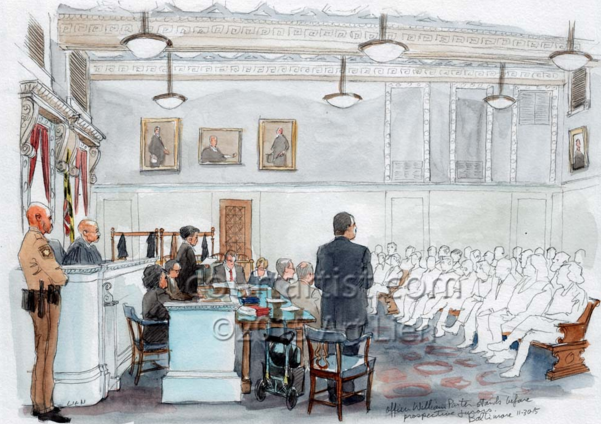

Jury selection was completed earlier Wednesday, with five black women, three white women, three black men, and one white man seated. Three white men and one black man will serve as alternates. Porter, the 26-year-old defendant, is black. He’s charged with involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, reckless endangerment, and misconduct in office.

Baltimore City Circuit Court Judge Barry G. Williams previously stated that Porter’s trial is scheduled to conclude by Dec. 17.

Porter is being tried first, prosecutors have stated, because he is expected to be a material witness in the case against Officer Caesar Goodson, the driver of the police transport van, where Gray’s severe spinal injury is said to have occurred. Goodson faces the most serious charges—including second-degree murder and criminally negligent manslaughter by vehicle—of the six officers going to trial. His trial is set for January 6.

Porter’s trial is expected to be a bellwether for the other police officers’ trials that follow. The potential witness list in Porter’s trial includes roughly 200 people, a majority of whom are Baltimore police officers, detectives, and ranking members of the department—likely to testify either to Porter’s character or problems within the department. Included on the list are Kevin Moore, the citizen who shot the video of Freddie Gray being arrested, former police commissioner Anthony Batts, and Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, who sat in the courtroom yesterday observing and occasionally consulting with the prosecution team. Also in court were members of Freddie Gray’s family and Baltimore Fraternal Order of Police president Gene Ryan.

The first witness was also called Wednesday. Baltimore police officer Alice Carson-Johnson, an 18-year veteran and academy instructor, trained Porter in emergency medical care as a cadet in 2013. She was asked by prosecutor Janice Bledsoe what officers are trained to do when someone requests medical assistance.

“I always teach the officers if someone requests for a medic, then you call for a medic,” Carson-Johnson said.

Emergency medical assistance for Gray was not called until six minutes after the transport van had arrived at the Western District police station and Gray was found unconscious.

On cross-examination, defense attorney Joe Murtha questioned if there was any post-academy emergency medical training for Porter and highlighted the challenges officers deal with in properly assessing whether individuals are experiencing an actual medical emergency.

“I can understand why the prosecution is putting her [academy instructor Carson-Johnson] on the stand first,” said University of Maryland law school professor Douglas Colbert, who has has been court observing the trial. “This is a crucial time—talking about the training Porter received.”

On the other hand, Colbert noted, the defense is trying to raise reasonable doubt “wherever it can right now.”