News & Community

The Middle Branch is in the Midst of a Shoreline Renaissance

An innovative project aims to restore the long-lost wetlands—and reconnect South Baltimore communities in the process.

From his desk inside Port Covington’s City Garage, ecologist Brett Berkley often feels the Middle Branch of the Patapsco River luring him and his co-workers out for a lunchtime walk. But while his GreenVest team works daily in support of this South Baltimore shoreline, their offices within a stone’s throw of its changing tides, that doesn’t always translate to as much facetime with the water as they’d like.

Even on a cold winter day in this otherwise visibly polluted, post-industrial landscape—interstate ramps, light and heavy rail lines, BRESCO’s towering waste incinerator, the muted drum of traffic rumbling across the Hanover Street Bridge—a brief escape outside can be quite restorative.

Despite its ailing state, the Middle Branch shoreline presents an alluring view into the natural landscape amidst the pulse of a busy city: squawks of gulls, gentle laps of waves, glimpses of ducks floating by or nesting osprey, an occasional blue heron gingerly plodding the surrounding grasses and sands as it fishes shallow waters.

“It’s very cathartic,” says Berkley, an ecologist and senior vice president for GreenVest, a Bowie-headquartered consulting company specializing in ecological resilience, restoration, and planning. “And that’s the whole point of what we’re trying to achieve here.”

With a full supply of reusable, dredged up muck from the Port of Baltimore, Berkley and a team of engineers, scientists, and other technical experts and contractors will spend the next few years restoring dozens of acres of depleted shoreline along this long neglected waterfront.

The city, partnering with the nonprofit Parks & People Foundation and the South Baltimore Gateway Partnership (SBGP), the casino revenue-funded economic development authority for this area, has tapped this technical team to help ignite a climate-resilience and biodiversity renaissance, with ripple effects for surrounding communities, too.

Their collective Middle Branch Resiliency Initiative (MBRI) looks to eventually add more than 50 acres of new wetlands, boosting the waterfront’s ability to mitigate increasingly frequent flooding and creating transformative new habitat for wildlife. And it will occur just offshore from some of the city’s most under resourced neighborhoods, which have grown more and more cut off from the rest of Baltimore by industry and infrastructure.

The MBRI is one of many layers in the grand vision of the Reimagine Middle Branch Master Plan, developed starting in 2019 and formally approved by the city’s Planning Commission in February. Led by renowned New York landscape architecture firm James Corner Field Operations, of the High Line fame, the plan’s better-known elements include 11 miles of shoreline trails, new parks, boat launches, fishing piers, and a since-completed recreation center for its neighboring Cherry Hill community, to name a few.

Neighbors are keenly aware of what has been lost to the shoreline’s long-term degradation, says Ethan Abbott, SBGP’s transformational projects manager. It’s a painful reality to gaze upon a riverfront underperforming, with littered beaches, spotty grasses, and diminished habitat for aquatic life.

“I think knowing that you have natural resources that are not of the quality that they should be, and what they deserve to be and that you deserve to have as a community, it’s very demoralizing to see,” he says.

But by prioritizing the plan’s wetlands restoration, Baltimore is at the forefront of cities pursuing an ever-elusive vision for a sustainable, equitable, and naturalistic waterfront. Re-establishing these areas just offshore—some 90 percent of which have been lost to erosion, dredging, and rising sea levels over the last 150 years—could transform the Patapsco as we know it, resulting in a rare influx of natural capital.

Waterfront edges today are generally considered yet-to-be developed sites for offices, residences, commerce, or even public parks. The MBRI has a different plan, aiming to instead help communities to reconvene with the water’s edge. The vision of the MBRI, and Reimagine Middle Branch more broadly, is to restore this waterfront with immediate benefits for neighborhoods, and without displacing those already living there.

“Cities across America have rediscovered their waterfronts and realized that, in order to be competitive in the 21st century, they need to be able to provide high-quality environmental and recreational amenities,” says Brad Rogers, SBGP’s executive director. “At the same time, there are cities that face resiliency challenges, and there are cities struggling with longstanding issues of environmental justice and racial justice. I would say we’re the only place where all three of those are being layered on at the scale we’re talking about.”

Few spots are better candidates for this work than the unremarkably titled “Site 5A,” just northeast of Hanover Street and Frankfurst Avenue in South Baltimore’s Brooklyn neighborhood.

BALTIMORE IS AT THE FOREFRONT OF CITIES PURSUING SUSTAINABLE, EQUITABLE, AND NATURALISTIC WATERFRONTS.

From her office on Hanover Street, Meredith Chaiken has seen the fallout of this depleted, marshy area becoming increasingly inundated during heavy rains and tidal overflows.

“That space is shared by a lot of people and it floods all the time, so it takes a tricky situation and makes it worse,” says Chaiken, executive director for the Greater Baybrook Alliance, a nonprofit community development corporation serving Brooklyn, Brooklyn Park, and Curtis Bay.

Soon, though, it will be transformed. In October, federal, state, and local officials announced nearly $48 million in funding, including almost $32 million from a Federal Emergency Management Agency grant, to fund the MBRI’s first of multiple phases. It starts with Site 5A, followed by three areas outside MedStar Harbor Hospital in Cherry Hill, and a fifth fronting BGE’s Spring Gardens energy facility in Westport.

The design for Site 5A, created by GreenVest and Baltimore-based engineering firms BioHabitats and Moffatt & Nichol, is up to 10 acres, incorporating a medley of habitats—low and high marshes, subtidal zones, mud flats, “scrub shrub” (or woody vegetation) areas, clusters of taller trees—all surrounded by forested edges and collectively rising up in elevation toward the road. The marsh’s base will be rebuilt with recycled materials, composed largely of sediment stored in the Maryland Port Administration’s Masonville Cove and Cox Creek containment facilities.

Berkley explains that this dredge from the port channels, after being tested for toxic contaminants, will be reused as a foundational building block for the aquatic habitat restoration, providing a base for the wetlands. That base will then be capped by sand and topsoil to host plants, grasses, and trees.

Construction is set to start this fall; GreenVest and SBGP are still finalizing permits and designs with city, state, and federal input, while stockpiling dredge, plantings, and other materials. But the process is moving along, Berkley says excitedly. The first wetland will take an estimated nine to 12 months to install, with others expected to follow within the next half-decade.

At the neighborhood level, amid growing anticipation, some residents have wisely asked how to keep these marshes from withering away like others before them, says SBGP’s Abbott. Fortunately, “we are working with our design team to make sure that those elements are already taken care of,” he says.

Berkley explains that the new wetlands incorporate a “custom-vented design,” likening its layout to “dendritic connections like the branches of a tree.” Once in place, this frame will promote gradual accumulation of more sediment, known as accretion, so that it won’t simply wash away. It also allows the marsh to be “self-organizing,” he says: Tides can move through freely, yet it will be stable enough to weather coastal storm surges.

The promised benefits extend beyond keeping water levels low along a flood-prone shoreline. Sediment-depleted habitats not only fail to mitigate or clean polluted water; they also fail to sustain robust ecosystems. Conversely, more robust wetlands and healthier waters on the Patapsco can support everything from micro-organisms to insects, fish, and birds of prey—something representative of “the historic habitat continuum,” Berkley says. “We’re trying to reset the system from the base of the food chain up.”

He visualizes a swell in biodiversity: growing numbers of winged predators—cormorants, green and great blue herons, eagles, egrets—feeding on schools of hickory shad and white perch returning to the Middle Branch from other stems of the Patapsco out in Howard or Carroll counties. (Another positive byproduct: fewer “fish kills,” caused by pollution and effectively low water oxygen—a regular occurrence around the harbor.)

Habitat restoration has positive implications for the humans living nearby, too, notes Zeevelle Nottingham-Lemon, executive director of the neighborhood revitalization nonprofit Cherry Hill Strong. Generations of Baltimoreans have grown used to physical separation from the water, littering without grasping the implications for waterways, and not observing functional ecosystems at work.

“It’s a connection that has to be made,” says Nottingham-Lemon. “I think one of the important things is that this doesn’t just happen around Cherry Hill and around these neighborhoods, and also that people understand why this is happening and what we can do. Understanding the things that we—the big ‘we’—have done to degrade our environment, and the fact that we have gotten to a point with technology and science that we can restore some of that—and some of that natural balance of the world around us to thrive—is huge.”

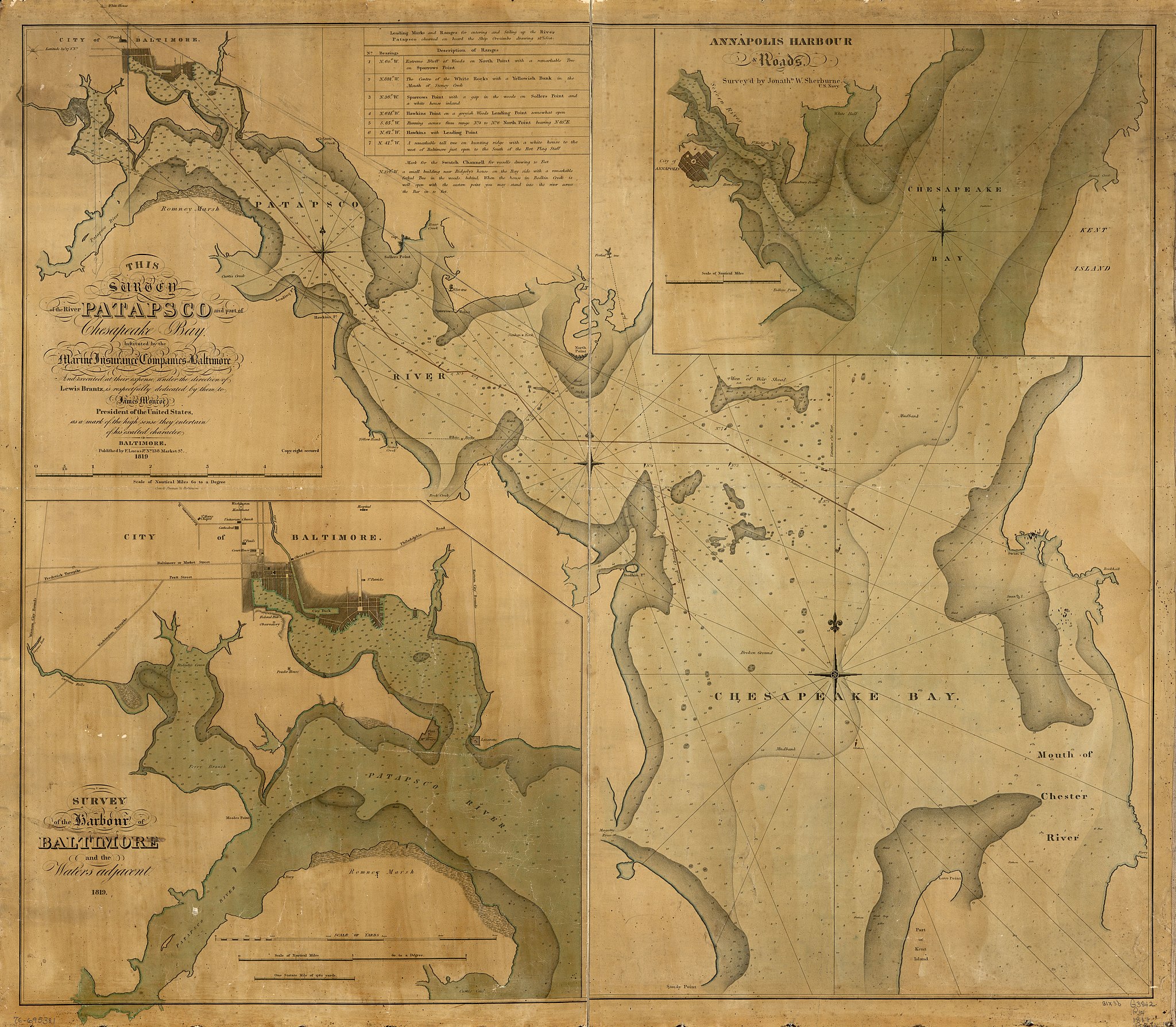

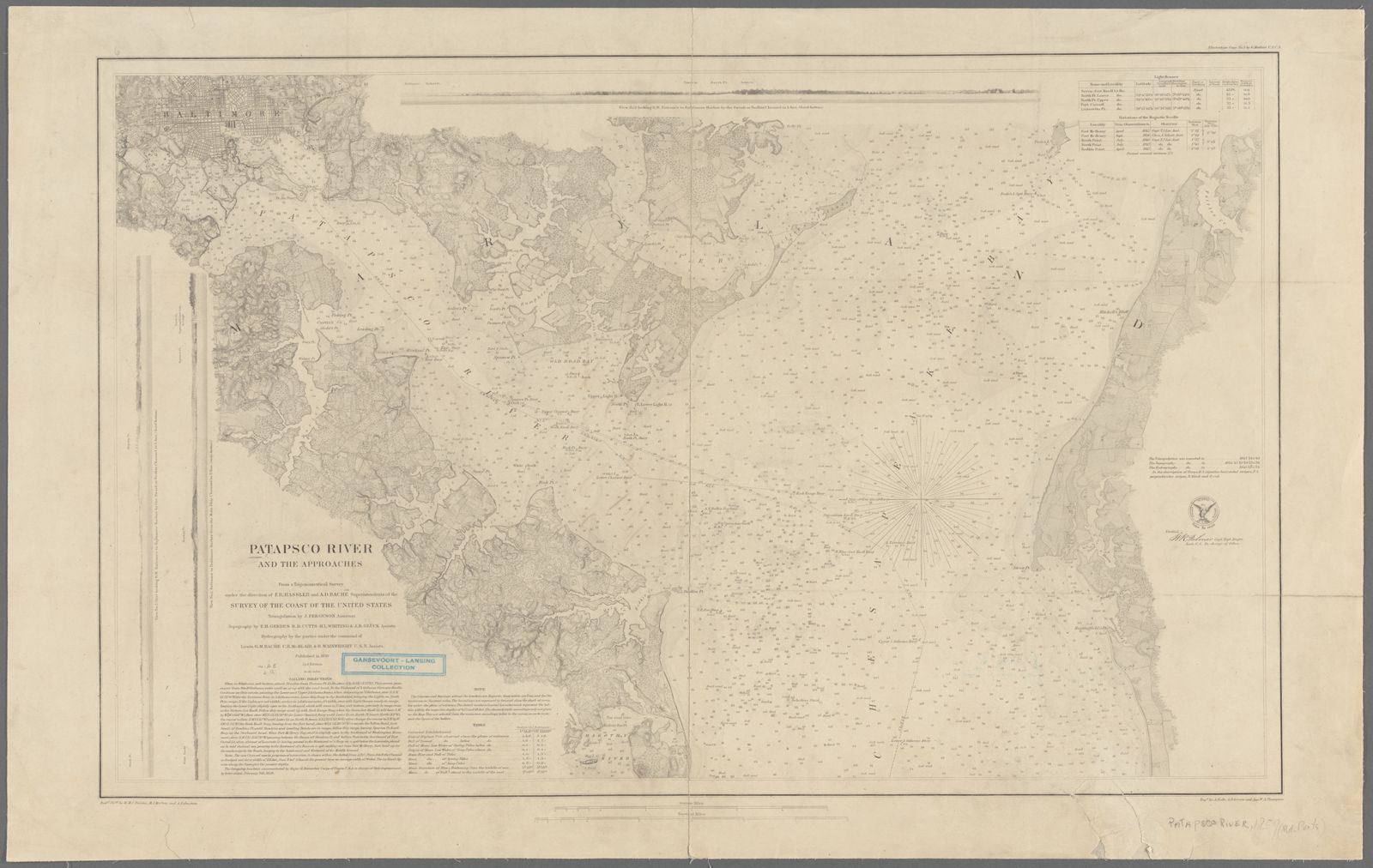

The history of local shoreline debasement dates back some 300 years here. In 1723, English merchant John Moale began mining his property at the mouth of the Gwynns Falls for iron ore while cutting down trees to power an industrial furnace. The land was also tapped for clay used to build Baltimore’s iconic rowhouses. Industry had yet to fully define the waterfront at the time of Lewis Brantz’s 1819 “Survey of the River Patapsco and part of Chesapeake Bay,” which depicts a soft shoreline with a generous delta and broader stems of the Patapsco River flowing in.

But a marked shift was underway by the mid-19th century, with the 1855 debut of a gas production plant at Spring Gardens near Westport, followed by the Carr-Lowrey Glass Company factory’s arrival next door in 1889, and a coal-burning power station in the early 1900s.

A network of rail tracks grew along the water’s edge, and on the peninsula across the water, the former War of 1812 stronghold of Fort Covington was redeveloped with mills, a distillery, and a wharf. The Western Maryland Railway would transform this area into a sprawling railroad terminal with much-desired water access, leveling the land and dredging up hundreds of thousands of cubic yards of shoreline sediment in the process. The Great Fire of 1904 also left its mark on the landscape, as journalist Dan Fesperman reported in The Sun nearly a century later: “Cleanup crews shoved much of the rubble right into the Middle Branch, filling marshes and narrowing the shoreline.”

By the 1930s, recreational access that Baltimoreans had enjoyed at famous sites like the Ferry Bar, a former beach and resort with boardwalks and piers, was significantly diminished. A 1932 aerial photograph depicts the Middle Branch more as we see it today: industry clusters in Westport and Brooklyn, the circa-1916 Hanover Street Bridge in full view, a since-abandoned freight swing bridge in active use between Port Covington and Westport, and a harder, if still-forested edge at what today is Middle Branch Park. Cherry Hill and Brooklyn are seen bordered to the east and west, respectively, by Reedbird Landfill, which was used as a city waste-dumping ground for the better part of a century.

“WE’RE TRYING TO RESET THE SYSTEM FROM THE BASE OF THE FOOD CHAIN UP.”

In the 1940s and 1950s, the city set aside 275 acres near the landfill as federal public housing for returning Black World War II and Korean War veterans, in the process founding Cherry Hill as Baltimore’s first planned Black suburb. Despite their proximity to the water, residents here and in neighboring communities like Curtis Bay and Brooklyn grew only more cut off as new industry, roadways, and rail tracks buffered the shoreline over the 20th century.

The Reimagine Middle Branch planners studying this history find it mirrors a familiar arc of urban waterfront development. There’s industrialization, where “you go from soft, green edges to bulkheads and factories and ports,” says Megan Born, a landscape architect and urban designer with James Corner Field Operations. Industry relocates elsewhere, usually to deeper water, and facilities become obsolete. Then, around the late 20th century, “you see the decline where we move from an industrial city to a post-industrial city.”

Amidst this arc, highway construction proceeds. On the Middle Branch, it occurred at a large scale, with new I-95 interchanges and flyovers carving up the waterfront. “The city, state, and federal highway system were prioritizing moving suburban folks through at the cost of the people in South Baltimore,” Born says.

Residents bear the burden of this physical separation and, ironically, quality-of-life pitfalls stemming from shoreline’s depletion, like flooding and resulting mold at home. Communities have periodically been promised change—the city’s earlier adopted Middle Branch Master Plan from 2007, for example, focused on restoring habitats, creating more recreation spaces, improving transportation, and more—and Rogers concedes that, fairly, neighbors have planning fatigue from unmet promises.

But there have been noticeable changes since Reimagine Middle Branch’s design process began in 2019. As new amenities materialize—the state-of-the-art, $23-million recreation center that opened in Cherry Hill last year, for example—there’s more cause to be hopeful.

“Actually starting to see projects that are coming to fruition is really exciting to [residents],” says Odessa Phillip of Assedo Consulting, a public outreach partner for Reimagine Middle Branch. “That’s what’s going to bring them back to the waterfront, and it’s what’s going to expose them to something they don’t know about with the ecology and the way that it serves them.”

Nottingham-Lemon has also seen an “intentional recognition” among partners to rebuild trust with strong public engagement. Examples include the Mobile Project Hub, which brought seven pop-up informal engagement sessions to surrounding neighborhoods and events last spring; Splash!, which drew hundreds out to paddle, row, and fish at Middle Branch Park in September 2021; Voices of the Middle Branch, a social media video interview series; and a partnership with the Environmental Justice Journalism Institute, which is producing a documentary and also putting young people to work with scientific data collection on water quality at a marina near Westport.

Arguably more important are ongoing check-ins with communities as the project advances. It can be difficult to include everyone—work and technology are real barriers for many residents—but the leaders of Reimagine Middle Branch have “seeded a system” of public involvement, says Nottingham-Lemon.

“What I think is really important is that they’ve taken an important historical scan and understand the need for leveraging this type of investment in South Baltimore.”

A walk along the Captain’s Trail at Masonville Cove offers a glimpse of the MBRI’s innate promise. The wildlife refuge, created by the Maryland Port Administration a mile west of Brooklyn, abruptly whisks visitors away from Frankfurst Avenue’s heavy industry to organic shoreline. A few birders are out walking, binoculars in tow, on a brisk February Saturday.

The Cove’s pair of nesting bald eagles—Baltimore’s first-ever known coupling—are perched on a branch about 50 yards away, overseeing it all, and there’s a gentle breeze in the air. The marsh’s pungent, muddy, brackish scent gets stronger toward the water, and suddenly you’re standing on soft Patapsco beachfront with a panorama of the Outer Harbor.

For most of the last century, this was a dumping ground for building debris, decrepit ships, scrap metal, timber, and more, but a cleanup effort and port-led restoration has revived it since the early 2000s. Taking up some 50 acres sandwiched among the port’s Fairfield Terminal, a CSX heavy-rail yard, and Vulcan Materials’ construction aggregates factory, Masonville Cove today is the city’s de facto proof-of-concept for urban wetlands restoration.

Baltimore, much like its Dutch sister city of Rotterdam, has been honing its craft with ecological restoration and sediment reuse for decades, from the filling-in of Hart-Miller Island State Park near Middle River beginning in the late 1970s, to the reconstruction of Poplar Island on the Eastern Shore starting in 1998, to the large-scale cleanup of Masonville Cove, next door to the port’s dredge containment facility.

The Middle Branch Resiliency Initiative is the next evolution, leaders say, in integrating scalable restoration with neighborhood life. Its success will be measured not merely in how it looks, mitigates flooding, or attracts new wildlife, but also in its ability to establish renewed human-nature connectivity.

“We should be able to see the Patapsco, feeling the presence of the water more than what we’re able to right now,” says Chaiken, of the Greater Baybrook Alliance. “The water should be a tremendous resource for the community, and it should be a piece of life in this community. The restoration and improvement of that green space, I hope it touches everybody.”