News & Community

Requiem: Fond Farewells

We say goodbye to the notable Marylanders we lost in 2014.

Courtesy of Todd Olzewski

Monica Pence Barlow, 36

When Monica Barlow, the Orioles public relations director since 2008, died not long into the team’s spring training this past February, players, coaches, and members of the media fought back tears, some unsuccessfully. Barlow succumbed to lung cancer, and had spent much of the previous five years since her diagnosis raising funds for and awareness of the disease for the nonprofit LUNGevity Foundation.

“Monica was able to walk that fine line between taking care of the players and handling all the responsibilities that come with being a club employee and taking care of the media’s needs and being a friend to so many of us,” recalls Roch Kubatko, who blogs about the Orioles for MASN. “More than one person in the organization told me that they felt as though she was celebrating with them after the Orioles won the division.”

To show their gratitude, Orioles players voted to donate a share of their post-season earnings to Barlow’s estate and to LUNGevity. Adds Kubatko, “I just hope she knew how much she was loved and respected inside that clubhouse.”

Daniel Bedell

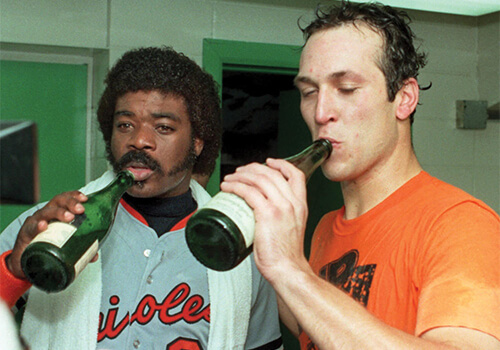

Frank Cashen, 88

When Frank Cashen took over as executive vice-president of the Orioles in late 1965, he boasted zero administrative or playing experience in baseball. He’d put in 17 years at the now-defunct News American (most as a sportswriter/columnist) and then six working for Orioles owner Jerry Hoffberger, first as publicity boss at Hoffberger’s harness racing track and later as advertising director for his National Brewing Company.

Improbably, through savvy trades (Hall of Fame outfielder Frank Robinson), inspired hires (manager Earl Weaver), and meticulous development of young players in the team’s farm system (third baseman Brooks Robinson), Cashen transformed the Orioles into a baseball behemoth. Under Cashen and director of player personnel Harry Dalton, the Orioles won four American League pennants and two World Series (1966, 1970), and then, with Cashen as general manager, two division championships after Dalton departed in 1971. Cashen himself left the team in 1975, and later guided the New York Mets to a 1986 world championship.

“Frank Cashen’s first big deal as a baseball executive exemplified his career—it worked on the field, in the clubhouse, and at the box office,” explains Stephen J.K. Walters, professor of economics at Loyola University Maryland and adviser to the Orioles. “When he and Harry Dalton stole Frank Robinson from Cincinnati in December of ’65, the city of Baltimore got just what it needed: a star and a leader who happened to be African-American and who would show his teammates and the fans just how good things could be here.”

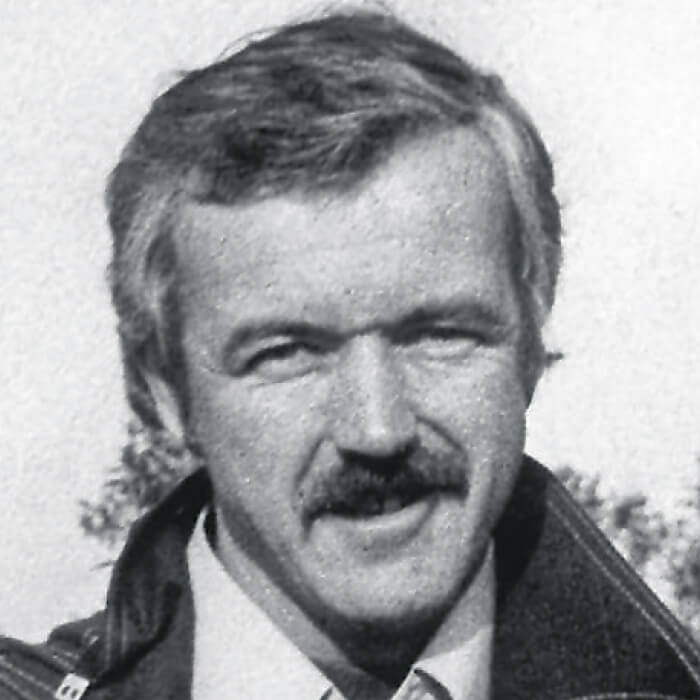

William G. “Bill” Evans, 83

Inventive, intrepid, jokey, and nimble with the language, Bill Evans applied his bulging bag of advertising tricks to campaigns for a gaggle of local products and services—Colt 45 malt liquor, McCormick spices, Ozite indoor-outdoor carpeting—while working at a series of Baltimore agencies from 1961 to 1992. His efforts earned him four Clio awards, the Oscars of the advertising universe.

But he left his most indelible mark with a slogan he wrote in the early 1970s as a public service to boost tourism in a Baltimore then plagued by a festering inferiority complex: “Charm City.” The phrase stuck, becoming part of the local DNA.

“Bill was an intuitive, clever copywriter,” says John P. McLaughlin, who worked with Evans at the Richardson Myers & Donofrio agency and later at their own firm. “I thought his special talent was writing for radio and the print media. He wasn’t without his complexities, and he wasn’t very patient . . . But [clients] eventually grew to appreciate the talent he brought to their businesses. His ‘Charm City’ copy was a brilliant branding line for the City of Baltimore.”

Courtesy of Deborah Wing Korol

June Wing, 98

June Wing walked the walk and talked the talk of an old-school 1960s leftie, building coalitions, educating the public, and working within the system on a host of social, environmental, and political issues, both locally and nationally.

At the height of the Vietnam War, she attended the raucous 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago as a supporter of anti-war presidential candidate Senator Eugene McCarthy, and in the late 1960s participated in the successful effort to stop “The Road,” the proposed multi-lane East-West Expressway that would have rolled through the Inner Harbor, Fells Point, Highlandtown, and Canton.

In pursuit of her ideals, Wing served as president of both the Baltimore chapter of the League of Women Voters and the Maryland chapter of the Committee for a Sane Nuclear Policy. “Nuclear issues were of central concern to her,” says Mary S. “Mimi” Cooper, a teacher and activist who is a former member of the board of the Rachel Carson Council. “June enriched the lives of many with her wit, keen mind, and her willingness to question and seek solutions with others.”

Courtesy of Maryland State Archives

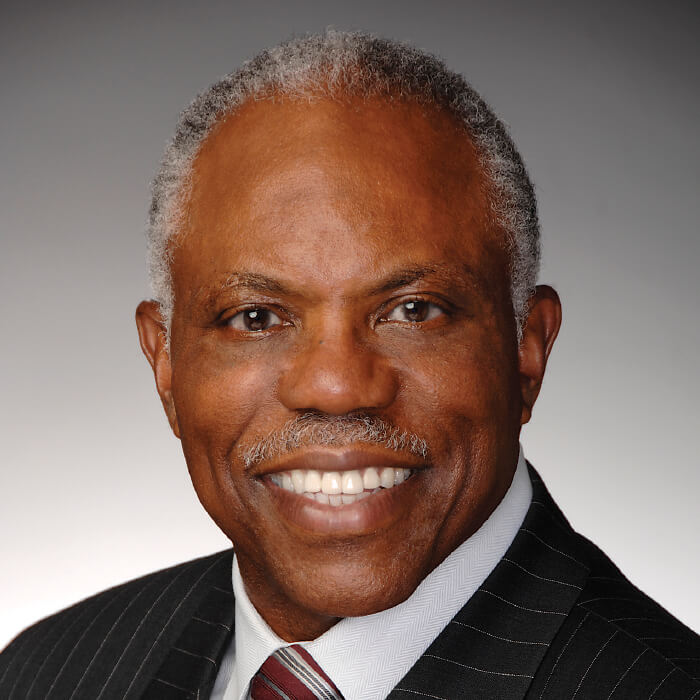

Bishop Lee Robinson Sr., 86

When Bishop Robinson joined the city police department in 1952, segregation still permeated its ranks, with black officers forbidden from patrolling white neighborhoods. Over the next 35 years, Robinson’s constant professionalism in a panoply of leadership roles—commander of Eastern District, chief of Patrol Division, head of Operations Bureau, deputy commissioner, and, finally, the city’s first African-American police commissioner in 1984—helped to remove barriers for blacks in the department.

“He was a trailblazer in many ways,” recalls Fred Bealefeld, the city’s police commissioner from 2007 to 2012—Bealefeld joined the force in 1981—and who now holds the position of vice-president and chief global security officer at athletic-wear company Under Armour.

“He encouraged all of us to do better and dedicate ourselves to service,” adds Bealefeld. “He was a man that I could reach out to at any time and get advice without concern. He was patient, nonjudgmental, and kind, and I always felt reassured by him.”

After he stepped down as commissioner in 1987, Robinson served as secretary of the state Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services for 10 years, and, later, as Maryland’s juvenile justice secretary for four years.

“When I think of commissioner Robinson,” recalls Bealefeld, “I will always remember how confident and sure he was, and of the positive spirit he evoked in all of us.”

Erika Nortemann, Oyster Recovery Partnership, Inc.

Torrey C. Brown, 77

As a Johns Hopkins medical doctor and head of its hospital’s emergency room, Torrey Brown gained considerable experience administering to the needs of sick patients. As chair of the Environmental Matters Committee in the state House of Delegates, Brown became acquainted with the state’s land, water, and wildlife problems. He put those dual backgrounds to effective use when, in 1983, he took over as secretary of the state’s Department of Natural Resources.

His 12 years in the post included imposing a moratorium on striped bass fishing that revived depleted rockfish; supporting projects that reduced damage from acid mine drainage into the North Branch of the Potomac; promoting Program Open Space to protect Maryland’s lands; and urging passage of the Critical Area Act, which prevented pollution by curbing development along the Chesapeake Bay.

“Torrey had the gift of being able to work with everyone,” says Chesapeake Bay Foundation President William C. Baker. “He truly loved Maryland’s natural resources and the Chesapeake Bay, and stood firm in their defense.”

Courtesy of John Lederer

Zachary Lederer, 20

Snapped by his father, the photo of Zach Lederer shows him lying in his hospital bed one hour after 2012 surgery for a brain tumor, his biceps flexed proudly in a muscleman’s pose. Zach immediately posted the image to his Facebook page. Soon others, friends and total strangers alike, did the same, and the photo of him “Zaching”—similar to the one below—went viral.

Diagnosed with a brain tumor at 11, Zach was given little chance to live another year. Remarkably, he recovered and went on to excel as a student—and play football—at Centennial High School in Howard County, and later enrolled at the University of Maryland, College Park, where he served as a manager for the men’s basketball team until his illness forced him to withdraw. Zach died this past March. But Zaching lives on.

“I don’t know what it is about [Zaching], if endorphins get going or what it is, but it does make you feel good,” his mother, Christine Lederer, said in an ESPN report. “And it just symbolizes hope and courage to me—not just for Zach, but for anyone going through a debilitating illness right now.”

Courtesy of The Whiting-Turner Contracting Company

Willard Hackerman, 95

A lifelong overachiever, Willard Hackerman graduated from The Johns Hopkins University’s School of Engineering at age 19 in 1938 and then joined the city’s then-tiny Whiting-Turner Contracting Company. Eight years later, he ascended to the firm’s board, and, in 1955, became president and CEO.

Under Hackerman, Whiting-Turner mushroomed into the nation’s fourth-biggest general builder, with 2,500 employees, Towson headquarters, and 33 regional offices. Its signature local projects include Harborplace, M&T Bank Stadium, the National Aquarium, Joseph Meyerhoff Symphony Hall, Johns Hopkins’ academic and medical campuses, and the University of Baltimore’s striking new Angelos Law Center.

“Whiting-Turner is one of the giant companies that has built Baltimore over the past 60 years,” says M.J. “Jay” Brodie, former president of the Baltimore Development Corporation (BDC). Adds Kimberly Clark, current BDC executive vice-president, “Willard Hackerman may be best known [for his] legacy of the physical developments throughout the city, but more important are his philanthropic activities and support of foundations and nonprofits.”

That philanthropy, through Whiting-Turner and personally, has benefitted arts (The Walters Art Museum), educational (Hopkins, Notre Dame of Maryland), healthcare (Sinai Hospital), and cultural (The Associated) institutions.

“Willard Hackerman embodied tzedakah,” notes Brodie, “the Hebrew term for generosity without expectations of anything in return. I wish that I could have made a mold of him.”

Walter Lippmann

William Worthy, 92

With the Cold War at its frostiest in the 1950s and 1960s, Baltimore Afro-American foreign correspondent William Worthy boldly went where few reporters dared: Moscow, talking to just plain folks and interviewing soon-to-be Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev; mainland China, speaking with ordinary citizens, quizzing premier Zhou Enlai, and interviewing American POWs from the Korean War; and Cuba, where he interviewed Fidel Castro and reported on race relations. In 1981, he toured Iran in the wake of its Islamic revolution and the takeover of the U.S. embassy there.

“William Worthy knew that the greatest attribute of a good foreign correspondent is the ability to reach the story, no matter who or what tries to stop you,” notes Dan Fesperman, thriller novelist and a former overseas reporter for The Sun. “In an era when his colleagues were easily cowed by travel bans and jingoism, Worthy got there anyway and delivered the goods, only to be punished by government officials. They took his passport, took him to court, and nearly took him to jail, but the one thing they never did was stop him.”

Clinton B Photography

Vivienne Shub, 95

For seven decades, Vivienne Shub cut a remarkable swath as both an actor and an acting educator, appearing most memorably at Center Stage and Everyman Theatre, while supervising Center Stage’s Children’s Theater, teaching kids at the Creative Arts Workshop and Children’s Drama Center, and conducting drama classes at Towson University. She also served as founder and head of the nonprofit Baltimore Theatre Alliance, which supports local stagecraft.

“Vivienne was in one of the first shows I directed at Center Stage,” remembers the theater’s longtime artistic director, Irene Lewis. “Her role called for a French accent, and hers was good enough to convince the entire cast that she was French.”

In 2008, Shub capped her distinguished theater life in Viva, La Vivienne, her final production. “She touched so many people,” says Harriet Lynn, founder of the Heritage Theatre Artists’ Consortium and Shub’s cousin. “Whether knowing her from watching her perform, working with her on stage, or being her student, we knew we were in touch with a woman deeply and emotionally committed.”

Courtesy of Kimberley Amprey Flowers

Walter Amprey, 69

A Baltimore native, product of city schools (an Edmondson High graduate), and educator at the city’s Calverton Junior and Walbook Senior High schools, Walter Amprey knew the landscape intimately when he took over as Baltimore’s schools superintendent in 1991 after occupying various administrative posts in Baltimore County. He immediately embarked on a campaign of modernization and innovation, including bringing in one outside contractor to manage nine schools, and another to tutor faltering students.

“Dr. Amprey was selected to be superintendent based in part on the recommendations of a group of distinguished educators and elected officials who had knowledge of his experience as a successful administrator,” explains Kurt Schmoke, who, as Baltimore’s mayor, appointed Amprey, and who now serves as president of the University of Baltimore.

However, when pupils’ test scores failed to appreciably increase, Schmoke agreed to relinquish to the state some governance of city schools in exchange for a massive infusion of financial resources, in effect, putting Amprey out of a job when both he and the school board were replaced.

“That controversial but important decision significantly benefitted the children of Baltimore City,” notes Schmoke, who points out that, throughout the contentious process, Amprey remained “an energetic and inspirational advocate for Baltimore City public schools.”

Jim Burger

Nelson Carey, 50

At his subtly elegant Belvedere Square wine bar, Grand Cru, owner Nelson Carey created an atmosphere of relaxed bonhomie for everyone—employees, regulars, and newcomers.

“Nelson’s desire was to create the kind of place where he and his friends would like to hang out,” says longtime bartender Charles Vascellaro. “Working at Grand Cru always has felt more like being part of a club and less like an actual job, and that feeling has been extended by the staff to the people who also come in to hang out there—a feeling of casual intimacy.”

Carey immersed himself in Grand Cru, always striving to improve the place, including studying to be a master sommelier, a task he’d nearly completed when he died.

“At Belvedere Square and Grand Cru, all are welcome and welcoming in the spirit of shared community,” notes Bill Struever, a principal at Cross Street Partners, which manages Belvedere Square. “There was no greater ambassador for this spirit than Nelson Carey, who, through his wit and wisdom, was a beacon of good cheer for all.”

Fouad Ajami, 68

A prolific author and frequent TV news talking head on Middle East history and political affairs, he advised high-level Bush administration policymakers to

invade Iraq, all while serving as director of Middle East studies at The Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies from 1980 to 2011.

Dale Austin, 81

Thoroughbred racing beat reporter for

The Sun

doggedly covered headline stories, including three Triple Crown winners and, most significantly, the 1970s “St. Valentine’s Day Massacre” race-fixing

scandal at old Bowie Race Track.

Michael Beer, 88

Biophysics department chairman and Krieger School of Arts and Sciences associate dean at The Johns Hopkins University

also was a dedicated environmentalist, leading efforts to clean up and rehabilitate Stony Run in North Baltimore and the Jones Falls.

Betty G. Bertaux, 76

Children’s Chorus of Maryland founder developed a meticulous, rigorous training program that not only taught

pupils how to sing, but also imparted musical intelligence. Her 30-student concert choir earned plaudits performing locally, nationally, and

internationally.

Leo Bretholz, 93

Austrian-born Holocaust survivor eluded Nazi pursuers from 1938 to 1945, including a daring escape from a train deporting him to Auschwitz. Settling here after the war, he spoke often to school groups about

his experience, while also lobbying locally and nationally for reparations from the French national railway, which transported Jews to death camps. His efforts met with success shortly after his death, when the U.S. and France reached a reparations accord.

John Hanson Briscoe, 79

Elected to the House of Delegates from St. Mary’s County in 1962, he worked on civil rights, abortion rights,

and environmental issues, ascending to lead the body as speaker from 1973 to 1979. Later served as a Circuit Court judge in Southern Maryland.

Dunbar Brooks, 63

Longtime urban planner for the Baltimore Metropolitan Council also served as the first African-American president of the Baltimore County school board and head of the State Board of Education, advocating for improved academic resources for African-American boys.

Robert E. Cooke, 93

Director of The Johns Hopkins University’s pediatrics department and Hopkins Children’s Center also helped shape policy in the creation of the national Head Start program

and the National Institute of Child Healthand Human Development in the 1960s.

Rhoda Dorsey, 86

As Goucher College’s first female president, she shepherded its difficult transition from a longtime all-women’s

school to a co-educational one in 1986, thereby ensuring its financial stability and increasing enrollment.

Octavia Dugan, 98

Her well-appointed Village of Cross Keys women’s clothing boutique, Octavia, featured the kind of elegant, traditional wear—ensembles tailored suits, and evening dresses that reflected her taste—that never goes out of fashion.

William Voss Elder III, 82

As curator of the White House in the early 1960s, he advised First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy on antique

furnishings, and then spent more than 30 years as curator of decorative arts at The Baltimore Museum of Art, appreciably enlarging its collection.

McKenzie Elliott, 3

Killed by an errant bullet during a drive-by shooting in Waverly this past summer, her death further outraged a city already weary

of senseless murders. At press time, no one had been arrested in connection with

the crime.

Joan Erbe, 87

Much-admired painter’s distinctive style featured vividly colored canvases filled with phantasmagorical, harlequin-like “people” arranged in tableaux that commented wryly on contemporary culture and society.

Robert W. Gibson, 89

Transformed Sheppard Pratt psychiatric hospital as its medical director from 1963 to 1991, putting the facility on

secure financial footing, desegregating staff and patients, setting up a public community mental health center, and introducing numerous other facility reforms.

Allen Grossman, 82

Multiple prize-winning poet, including a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” he taught as The Johns Hopkins

University’s Andrew W. Mellon Professor of the Humanities from 1991 to 2006, wowing students and faculty alike.

Levin F. “Buddy” Harrison III, 80

The self-dubbed “Boss Hogg of Tilghman Island” ran an Eastern Shore empire that comprised a

charter-boat fishing operation popular with high-ranking Maryland politicians, a comfy country inn, and a renowned seafood restaurant.

Sam Holden, 44

Personable freelance photographer for City Paper, this magazine, and national publications excelled at

everything from journalism assignments to art images, developing an instant rapport with his subjects, particularly members of the local rock music scene.

Shirley W. Johnson, 91

Parkville mom joined the state’s fledgling Mothers Against Drunk Driving chapter after her son was killed by a

drunken driver. As the group’s president, she lobbied legislators for tougher laws, fought for court monitoring of drunken-driving cases, and spoke to

students about the perils of driving while drunk.

Gregory Kane, 62

Native Baltimorean brought a contrarian, conservative voice on local and national issues to his Baltimore Sun column, particularly those pertaining to African-American affairs. Also co-wrote an award-winning three-part series on slavery in

Sudan.

Robert L. Karwacki, 80

Miles & Stockbridge law firm partner assumed the presidency of the city school board in 1970, helping to choose the city’s first black schools

superintendent. He went on to serve as a city Circuit Court judge, as well as a member of the state Court of Special Appeals and Court of Appeals.

Charles “Les” Kinion, 78

Running enthusiast who co-founded the Baltimore Road Runners Club in 1970. Three years later, with two

partners, he hatched the Maryland Marathon, which looped from old Memorial Stadium to Peerce’s Plantation in Baltimore County.

Charles Lamb, 87.

As the “L” in the powerhouse architectural firm RTKL, he brought a modernist vision to his designs for GBMC,

downtown’s federal courthouse, and the award-winning John Deere warehouse in Timonium.

Theo Lippman Jr., 85

Courtly Baltimore Sun editorial page writer brought keen analysis, deep and broad knowledge,

and ardent thoughtfulness to his current affairs columns, illuminating not only politics, but also the human condition.

Earl Morrall, 79

When star Baltimore Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas was injured in a 1968 preseason game, Morrall stepped in to lead

the team to a 13-1 record and two playoff wins, before losing the 1969 Super Bowl. He again subbed for a sidelined Unitas in the 1971 Super Bowl, this time

steering the team to victory.

John Ostrowski, 72

Oversaw operations at his family’s celebrated Ostrowski’s Famous Polish Sausage market in Fells Point, adhering to

his grandfather’s and father’s recipes to create superb, handmade seasoned pork products, notably kielbasa. Poor health induced him to sell the business in

2013.

Burt Shapiro, 68.

Insightful WBJC culture vulture produced jazz programs, plus numerous shows on classical composers

and a five-hour Frank

Sinatra special, while also serving as managing editor of the station’s program guide and as its resident film and theater critic.

Leon B. Speights, 74

Customers from all social strata lined up to buy the barbecued smoked ribs, minced pork, and fried chicken, plus a

handful of Southern sides, at his Leon’s Pig Pen shops, which dotted the city from the late 1960s through the early ’80s.

Irving J. Taylor, 95

Innovative psychiatrist and administrator who turned Ellicott City’s Taylor Manor Hospital into

a national leader in the treatment of mental illness and substance abuse, notably pioneering the use of anti-psychotic medication and establishing a unit

dedicated

to teens.

Patricia Waters, 89

Along with her husband, she raised four children, including son John, to appreciate the arts, encouraging John’s

incipient fascination

with filmmaking, which resulted in

his first effort, shot

in the family’s Lutherville home.

Herman L. Wockenfuss, 92

Candymaker best known for the dozens of chocolate creations, especially nonpareils, made at and sold from his

family’s Harford Road shop. He expanded the Wockenfuss brand’s reach with outlets throughout the greater metro area.