Last Friday night was Erev Rosh Hashanah—the eve of our holiday celebrating the beginning of a new year. I had just finished watching a beautiful service—on my laptop—surrounded by my four kids. The air was crisp and the sky was beautiful, so I took my glass of wine and sat outside on the porch while my daughter did skateboarding tricks in our front yard.

Suddenly, my phone buzzed. I looked down to a link to an article and a simple expletive word with a lot of k’s and even more exclamation marks.

“No,” I simply said to myself. I took a deep breath and opened the text. “No.”

A Jewish teaching says those who die just before the Jewish New Year are a “tzaddik”—a righteous person. They are the people God has held back until the last moment because they were needed the most.

“And so it was,” tweeted NPR Supreme Court reporter Nina Totenberg, also Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s bestie, “that #RBG died as the sun was setting last night marking the beginning of Rosh Hashanah.”

I knew Ruth Bader Ginsburg couldn’t live forever. But it sure felt like she should.

We are big fans of RBG in our house. Not just because she was a kick-ass woman (and a kick-ass Jewish woman) but because her selfless contributions were endless. She was someone my daughter Willa, 11, looked up to in infinite ways. Our infatuation with RBG has ramped up the last few years as Willa has become more aware of her role in this world and the injustices that women still face. For many Halloweens, Willa chose as her costumes (maybe with a little nudging from me) strong women: Rosie the Riveter, Frida Kahlo and two Halloweens ago—Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

She wore the costume to the Great Halloween Lantern Parade and Festival in Patterson Park—the big glasses, black robe, gray bun, and jabot. A woman on the hay ride smiled at Willa, “Are you Judge Judy?”

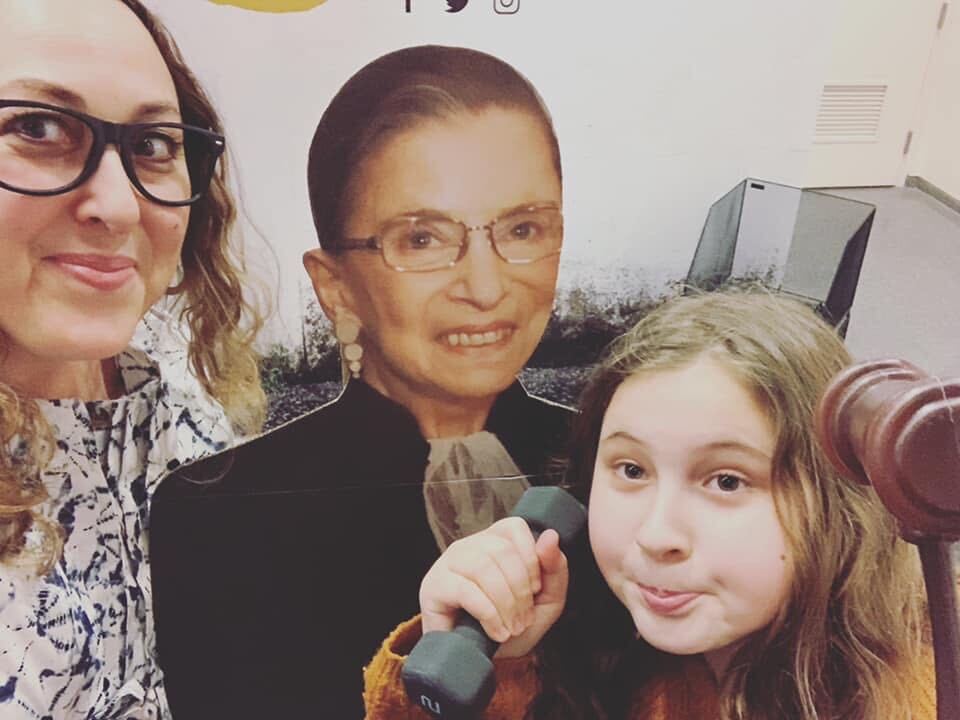

Last January, the day before Willa’s 11th birthday, we headed to see Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a retrospective at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia that traced her career and rise to icon status. (I really hope this wonderful exhibit resurfaces post-pandemic.)

We have books about RBG, bobble heads, and we’ve seen all the movies and documentaries. Our holiday card one year was an illustration of RBG. “Hope your holidays are supreme” one side read, and the other “Merry Resistmas.” A few years ago, Willa returned from a visit to Austin, Texas with a prayer candle with RBG’s face on the side. We would burn it every time her name was in the news—from court decisions to cancer battles to hospital stays. Last month while in Rehoboth Beach, I spotted another RBG prayer candle. I mentioned to my mom that my original candle was almost finished, and I was worried what would transpire if it burned out. “We can’t let that happen,” she said, before buying me the replacement. (“The candles didn’t work,” my friend Talley texted me as soon as the news broke. Everyone knew about the candles.)

Late Friday night—as I waited for my apple bundt cake to bake—a Baltimore friend messaged that she was at the Supreme Court. There were Hebrew prayers, and someone had blown the shofar, she reported. “I should have gone,” I told her. “You still can,” she gently nudged.

I barely slept that night. At 6 a.m., I slipped out of bed and went into Willa’s room. “Do you want to go say goodbye to Ruth?” I whispered. We were in the car by 6:20 and pulled up to the Supreme Court at 7:15.

The air was cold. The sky a baby blue. Under normal circumstances, I’d be home getting ready for Rosh Hashanah services, forcing my boys into button downs, and trying to remember to bring our yarmulkes. But nothing is ordinary anymore. Instead, I was standing in front of the Supreme Court mourning RBG.

National media gathered in one area, while local news stations wandered amongst the visitors. When we arrived, there were already piles of flowers, illustrations, notes, American flags, prayer books, love letters, and lots of candles. We tried to take it all in.

Many posters read: “May her memory be a blessing” and “Rest In Power.” Another: “These flowers are from our wedding. Without RBG we wouldn’t have been able to get married. Thank you for being our champion.” And another: “I will pass the bar for you.” Tears slid down my face. The flag hung at half-mast over our heads and the impressive 16 marble columns loomed behind a police barricade.

A TV reporter from the local Fox affiliate approached and asked if she could speak to us. We said yes. A reporter from The Lilly—a women’s publication from the Washington Post—asked us questions about why we had chosen to come that day. Another reporter from the local ABC affiliate came over and asked if she could interview us on air. “Everyone here must be able to feel how much we loved RBG,” I told Willa. (Before also wishing I hadn’t gotten dressed in the dark.)

People wandered around—all wearing masks—snapping pictures and shaking their heads, crying, hugging. There were babies in strollers and dogs on leashes. Willa and I quietly read the Mourner’s Kaddish—a Jewish prayer said during the bereavement period of loss. I read it in Hebrew and Willa read the English.

Yit’gadal v’yit’kadash sh’mei raba.

We took our original RBG candle—the one from Austin—held it in our hands and then placed it amongst the growing shrine.

After an hour, we left to seek warmth and coffee—our cheeks pink from the cold air.

Later that night we celebrated Rosh Hashanah as good Jews do—with food and family. We brought our bobble head Ruth, the second candle, and an RBG paint-by-number to decorate my parents’ holiday table—each item nestled amongst the Manischewitz, challah, pickles, and matzo ball soup.

“Let’s toast Ruth,” my mom said. Willa stood up and raised her glass of grape juice, “She was my hero.”