News & Community

On The Wrong Track

Special report on the crash of Amtrak Colonial 94.

At a little past 1:30, paramedic John Waskevitz and his wife are off to do some shopping. They heard an explosion a few minutes ago, but it sounded like another artillery test at the Aberdeen Proving Ground on the other side of the river. Waskevitz notices a column of dark smoke to the north. The firehouse alarm sounds. He heads for the smoke. At the tracks he sees people removing suitcases from some of the rear cars. Waskevitz, the first emergency worker on the scene, makes his way to the wreckage through clusters of dazed survivors.

He climbs onto the mangled car perched unsteadily at the top of the wreckage. It is passenger car 21236. He looks into the smoke-filled car and sees a mass of seats broken loose. He wriggles inside through a broken window. One victim is buried under the seats. He checks for a pulse in her neck and feels none. He digs farther, snaking along on his hands and knees, on his stomach, stashing debris behind him like a mole. He comes to another victim, her neck apparently broken. She is also dead.

The images flicker in his mind, sometimes when he’s driving, sometimes when he’s trying to sleep. He finds himself aboard the train in the moments surrounding the crash. He sees the impact in slow motion, hears the roar, feels the sudden grip of steel twisting all around him.

Months after the fiery wreck of the Colonial, Dr. Roger Horn still imagines it a dozen times a day.

In a hot and crowded congressional hearing room in July, he finds space to sit cross-legged on the floor, balancing a heavy briefcase on his lap to take notes. He has testified many times since that Sunday afternoon in January when sixteen people died in the collision of the Amtrak passenger train and three Conrail locomotives near Baltimore. Now he waits his turn to take his private anguish public once again.

A big man, the mathematics professor stretches his back and shifts uncomfortably. He will not testify for hours. Across the room, a high-ranking staffer in the Federal Railroad Administration turns to an assistant. “That’s Dr. Horn,” he whispers. “His daughter was killed.”

At 7 o’clock on Sunday morning, January 4, it is clear and dry, 27 degrees and still dark outside the pretty, blue Victorian home at 13 Maple Avenue in the Overlea neighborhood of Baltimore. Denise Evans can hear her husband rustling in the hallway with 2-year-old Joshua, and she knows exactly what’s coming. “C’mon,” she hears Jerry whisper. “Let’s go get Mommy.” He picks up their son and carries him like a football into the kitchen for breakfast.

At the table they snatch bacon from each other when Denise isn’t looking and giggle at their mischief. Joshua has his father’s nose. Jerry gets up several hours before work each momingjust to be with him.

This morning father and son splash in the bathtub together before Jerry departs at 9 a.m. At the front porch the lanky, 35-year-old Amtrak engineer presses his lips on the door where he and Denise kiss each other through the Plexiglas. Joshua giggles again.

Today Jerry will operate Amtrak’s Colonial 94, scheduled to depart Washington’s Union Station at 12:30p.m., bound for Boston. He winks and gives Joshua a father’s exaggerated wave and promises to be home by 11 p.m.

On a small farm in Potomac, Maryland, 20-year-old Christy Johnson is trying to administer a shot to one of her family’s horses. The animal bucks and turns, knocking the syringe from her hands. It disappears into the straw on the barn floor.

Christy was hoping to catch a morning train so she could spend the day with her sister in New York before flying back to Stanford University in California. But she’s late, and now it looks as if she’ll catch the 12:40 at New Carrollton.

Christy’s parents, Arthur and Ann Johnson, say good-bye and go off to Georgetown Presbyterian Church. They are feeling food about their daughter, who five years ago had started to abuse drugs and had reached a low point in her life. She had gone to her parents, gotten counseling, and within a year was off drugs and helping other kids with the same problem.

Now as she approaches graduation from Stanford, she is weighing a career in psychology or health care.

On their way to church, her parents pass Rebecca Hyman, one of Christy’s closest friends from high school. Rebecca is on her way to pick up Christy and drive her to the train station. Another old friend joins them at the house and they make small talk over coffee in the kitchen.

Christy runs up to her bedroom to finish packing and Rebecca follows, trying to squeeze in a few more minutes together.

They head out the Beltway to New Carrollton, hitting 70 miles an hoµr as Christy keeps nagging: “We’re going to miss this train.”

At the station Rebecca helps Christy with her luggage and they quickly hug. “I love you,” says Christy.

In the Pennsylvania town of Shippensburg, 18-year-old TC Colley is ending a long stay with his father and stepmother. He’s going back to Baltimore, where his mother lives and where some letters from his new girlfriend await him. Then he’ll take the train up to Providence, where he’s a freshman in photography at the Rhode Island School of Design, determined to be the next Ansel Adams.

TC and his father had a heart-to-heart talk last night about growing up. It seemed that TC was testing out his latest personal style, a penchant for frankness, and his father wanted to rein him in a bit. ”Just be sweet,” added his stepmother, Susan. “Just be you.”

Tom Colley drives his son to the usual rendezvous point near York, and watches him throw his coat in the back of his mother’s car before they drive off for Baltimore.

In the wooded hills of northern Baltimore County, 16-year-old Ceres Horn is canvassing her family’s home for belongings before returning to Princeton, where she’s a freshman honors student two years younger than most of her classmates. One thing she doesn’t want to forget is the heavy wool sweater she bought for her boyfriend back at school.

Her father, Roger Horn, a Johns Hopkins University professor, is in Israel lecturing on mathematics. Ceres and the rest of the family stayed up later than usual last night as her mother, brother, and sister gathered around her bed and she described how she’s cramming sports and theater into her heavy academic schedule. Her goal is to become an astronaut, and she’s going to try for a summer job in the astrophysics department atJ ohns Hopkins.

But this is Sunday morning, January 4, time to get back to school. Ceres, her mother, and her 9-year-old brother, Howie, drive to Penn Station in downtown Baltimore, where engineer Jerry Evans is about to pull up to Track 3, Gate C, at the controls of the Amtrak Colonial. He left Washington at 12:35 p.m., a few minutes late, but has made up most of that time.

The train is one of the modern Amtrak liners bought by the federal government to keep the country’s passenger-train system alive. Since the early 1950s, trains had lost more and more riders to airliners and cars, and by the late 1960s, when it became clear that no private railroad could afford to keep them going, Congress decided to create Amtrak as a national railroad. Amtrak lost millions of dollars every year, but taxpayers kept the trains running.

The retooled rail is especially attractive to New York-bound Baltimoreans since BWI, unlike Washington National, does not have a regular schedule of frequent shuttle flights.

Today Evans’s train includes two big General Motors electric locomotives and twelve passenger cars. About four hundred passengers are already aboard. Christy Johnson has moved as far to the front of the train as she could, to passenger car 21236, which is just behind an empty cafe car and the two locomotives.

On the platform, TC Colley’s stepfather, Cal Walker, a physics professor at Johns Hopkins, recognizes Ceres Horn’s mother. They introduce the two teenagers.

TC is loaded down with luggage. His mother, Ann, notices the wide stance he has adopted since taking up karate. He’s gotten so tall and broad in the last year, and slouches as if uncomfortable with his height. He’s dressed in the dark, heavy clothes that say artiste, with a new woolen scarf from his stepmother swooping around his shoulders. He wears a silver chain around his neck and an earring she’d recently given him.

Just a couple months earlier he was standing here asking her to tell him how he’d changed. She’d told hi.m he looked much more grown up and seemed more directed.

The Colonial pulls in, bringing with it a rush of cool air and a flurry of good-byes. “I love you,” Ann tells TC. ‘I’m very proud of you, and I think you’re wonderful.”

“So do I,” says TC.

“Good. We agree on it, then.”

She puts him on the third car from the end of the train. “Try going toward the back,” she says. “It looks like there are more seats back there.” But TC walks forward, as younger people do in crowded trains, walking through seven cars until he finds one with a lot of room-passenger car 21236, the same car Ceres Horn and Christy Johnson are in. About 175 passengers board the train in Baltimore. Including twelve crew members, there are now 579 people aboard the Colonial.

At 1:15 p.m., an Amtrak conductor barks over the radio to Jerry Evans, “Ninety-three, Jerry ninety-four, okay to proceed.”

“Okay,” says Evans, “ninety-four on the move.”

Susan Horn and young Howie are already out of the station when she remembers to mail Ceres’s letter to Johns Hopkins astrophysics professor Arthur Davidsen. She walks back and drops it into a mailbox.

“I’m very excited about the prospect of working for the Center for Astrophysical Sciences this summer,” Ceres has written. “It will give me a better understanding of what an astrophysicist actually does, and enable me to decide if majoring in physics at Princeton is for me.”

The Bayview freight yard on Baltimore’s east side has the old-fashioned look of most of the yards on the railroad system’s busy Northeast Corridor: rows of parallel tracks, a squat control tower, and a few cinderblock buildings and trailers painted in dull green and gray.

The buildings are plastered with safety posters, a different one each month. On the roundhouse wall there used to be a mirror etched: “Accidents only happen to the other guy. Meet the other guy.”

Today engineer Ricky Lynn Gates and brakeman Ed “Butch” Cromwell are scheduled to move three diesel locomotives 110 miles north and west for use in the Enola Yard outside Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

Railmen love this kind of duty—they call it “light engines”—because with no freight cars to pull, the locomotives have quicker acceleration and easier handling. A run with light engines is a piece of cake that comes maybe one time out of a hundred. Gates won’t have to worry about moving a long, heavy freight train, the buffeting and bumping of boxcars and tank cars on hills and curves. Cromwell won’t have to worry about brake-hose trouble or busted couplers. Just a short scoot up to Perryville, Maryland, then west to Enola Yard. They’ll probably make it in three hours, and then ride a bus back home.

Oates’s fee for the job is $121.06 each way, Cromwell’s $96.50. Lack of seniority has meant too much furlough time for both of them, and they feel lucky to get the work. January 4 still is considered holiday time by many of their coworkers, who have taken their day off.

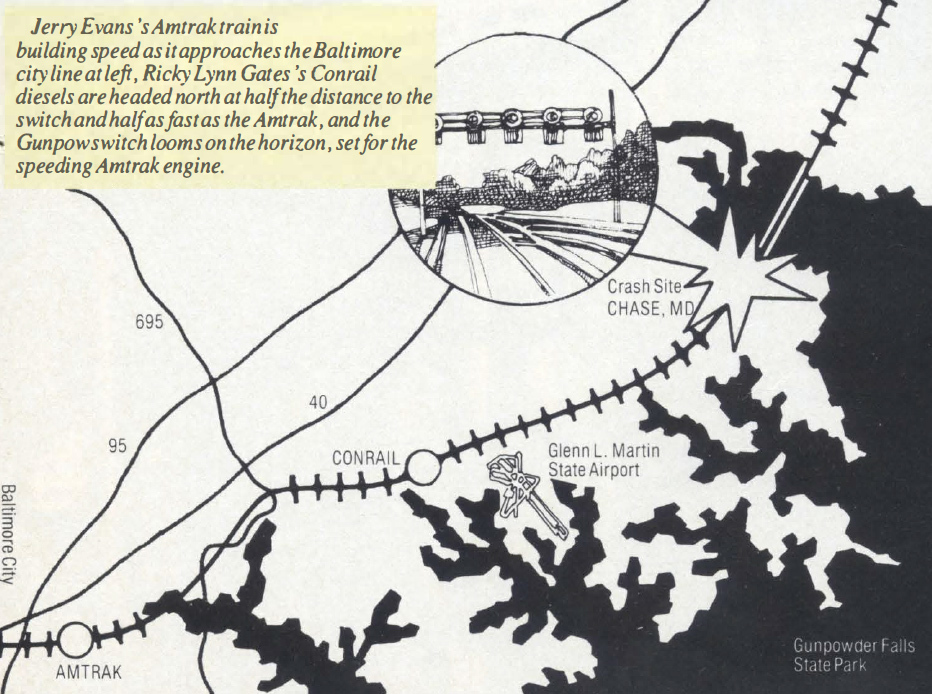

The two enter the terminal building for the paperwork. Gates registers and signs the safety sheet, which posts a daily safety rule. The paperwork tells him he should expect a routine delay at “Gunpow,” the first switch up the line, a half-mile south of the Gunpowder River Bridge, where the old wooden-tied freight line merges with the concrete-tied high-speed line of the Northeast Corridor. He ‘II probably have to wait there a few minutes for the passing of priority Amtrak passenger train, Jerry Evan’s train, which is one minute behind schedule.

Gates looks over the engines, checks in with trainmaster George Mince, and tells him the lead engine doesn’t have a working two-way radio. It’s a common problem, and they agree that he can use one of the shorter-range, hand-held models that brakemen using in walking the brake lines.

The trainmaster observes the two-man crew while they talk. It used to be that supervisors would just look for signs of drinking when crews check in. Today, as his drug-detection training has taught him, Mince also looks for other signs. he has been around the rails for thirty-six years, long enough to know how tough spotting a drug user can be.

At 32, Gates is a seasoned user of both alcohol and marijuana. Cromwell, 33, prefers marijuana, and sometimes other drugs. Gates is discreet about the illegal stuff, but some of his friends know about it. Most of them figure he knows how to stay in control on the job.

The alcohol problem did become a public matter late one night in December. A cop caught him waving down the road in his car. Gates couldn’t recite the alphabet, and he foolishly presented his open wallet with a $20 bill and $5 bill over his driver’s license, but the cop wouldn’t go for it. The details would emerge in a country courtroom some three months later, by which time there would be intense interest in the habits of Ricky Lynn Gates.

But today Mince doesn’t notice anything unusual about the crew. They look fit and ready to run four hundred tons of diesel locomotives the 110 miles up to Enola, and he sends them on their way.

The national rail system is in the best physical condition is has been in the last twenty-five years. The equipment is the best ever . . . But if eight-thousand-ton trains are entrusted to impaired crew members, disaster will not be avoided. -Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole, in a 1984 Senate hearing.

The railroad industry has waged war with alcohol for more than a century, and even today something of the traditional image of American’s trailblazing railroaders persists: hard-working and hard-drinking, rough loud, grimy.

A few visits to the workplaces and homes of today’s railmen dispel much of that image. Trailblazing has been supplanted by mortgages, tuition, and car payments. But many railroaders still drink on the job, and some use drugs as well.

Until twenty-one months ago, there was no federal law saying they couldn’t.

Every freight and passenger line in the country prohibits crew members from using alcohol or drugs or being impaired on the job. Rule G, as it’s known industrywide, has been around since 1897. The railroads designed Rule G to weed the abusers out of the working ranks, and violators traditionally have been fired.

But Rule G doesn’t work. That was made clear in a 1979 Department of Transportation study of234,000 railroad workers. It found that 23 percent of operating employees, including engineers and conductors, were problem drinkers, and that 5 percent of all employees came to work very drunk or got very drunk while on duty at least once during the yearlong study.

With little faith left in Rule G, the industry has been trying other ways to get substance abusers out of safety-sensitive positions. Some railroads and unions have formed Rule G bypass agreements that offer treatment as an alternative to termination. It can be voluntary, or workers can be referred to an evaluation-and-rehabilitation program by a ”prevention team” -two or more coworkers-or by a union official. Those who complete treatment can return to duty.

Although the railroad unions have historically underplayed the extent of drug problems among workers, it is the unions who now are pushing hardest for such “peer prevention” programs. While concerned about safety, they also would like to head off increased federal involvement. The unions and the railroads have long claimed they can police themselves against drugs and alcohol.

The Federal Railroad Administration, part of the Department of Transportation, is responsible for rail safety. Between 1975 and 1984, it investigated forty-eight accidents it says were caused by drug or alcohol impairment, accidents that caused thirty-seven deaths and $35 million in property damage. The accidents included three head-on collisions, a derailment at 68 miles per I hour on a 25-miles-per-hour curve, and the wreck of a one-hundred-car freight train carrying hazardous materials that forced the evacuation of a Louisiana town. In that wreck, both the engineer and the head brakeman were drunk and asleep.

Something more than self-policing seemed necessary.

Beginning in 1983, a group of FRA staffers under Administrator John Riley, a Reagan appointee, spent about three years writing a set of regulations they hoped would control the use of alcohol and drugs I in the industry. FRA regulations have the force of law.

For the first time, railroad operating employees would be prohibited by federal law from alcohol or drug use or ·impairment while on duty. Preemployment urine tests would be mandatory. Railroad companies would be required to conduct, and crews to submit to, toxicological testing after certain types of accidents.

Accident reports from the railroads, which the FRA depends on for most of its data, would include inquiries into the possible involvement of drugs and alcohol, even when no such involvement was obvious. Railroads would be required to establish voluntary drug-referral policies and Rule G bypass agreements.

Finally, railroads would have the right to require any operating employee to submit to breath and urine tests on the basis of” reasonable cause,” even when no accident had occurred. The unions fought that provision in court and lost.

In the context of the old railroad industry, the FRA’ s new set of rules seemed drastic when they went into effect early in 1986.

For engineer Ricky Gates, they didn’t make much difference.

Gates pulls his engines up to the signal-testing bay to check out the cab’s safety devices. From the engineer’s seat on the right side of the cab, he looks at the in-cab signal rack mounted on the window to his upper left.

The vertical signal looks like a downsized traffic light with four aspects, all a light shade of amber, with patterns of dots telling the engineer when to go, when to slow, when to prepare to stop, when to stop. It is activated electronically by switchers who sit in trackside towers along the route. It duplicates the larger, remote-controlled signals mounted over the tracks or on the wayside. Engineers bet their lives on them.

Some engineers will tell you that they’ve seen a signal mess up before, but that it usually “fails down”-tells them to go slower than they should, rather than faster. Signals telling them to go when they should stop- “false proceeds” -are rare. There have been nineteen of them in the Northeast Corridor in the last four years, none causing an accident.

A signal bulb in Gates’s cab is missing. It’s part of the signal telling him to slow down and prepare to stop. He doesn’t fix it. Engineers who linger too long over the little things are not popular in a business where time is closely linked with money.

Gates checks the alertor whistle, mounted on the floor behind his controlling console. It looks something like a flute and sounds like a shrill pennywhistle. It screeches loudly every time the train passes any signal that doesn’t say “go,” just to keep the crew paying attention.

Most engineers hate the whistle. Not only does it hurt their ears, it’s also insulting. They know it’s a safety device, but it makes them feel like lab rats and its presence questions their professionalism. Some engineers gag the whistles with a few inches of duct tape, but more often it’s taped by a brakeman, riding overnight in the cab of a second or third locomotive and trying to catch a few winks on a gently rocking freight train.

Gates tests his alertor whistle and hears nothing-or, at most, a faint hiss. He didn’t put the tape there. It is probably from an earlier trip. Gates has a reputation as a stickler for the rules, and normally he removes the tape.

But today Gates and Cromwell are in a holiday mood. Corridor traffic is low. They’re running light engines. Cromwell has along his personal radio. They might be able to listen to the San Francisco 49ers-New York Giants playoff game.

And one of them is packing a couple of marijuana joints.

At 1:13 p.m. the engineer and his brakeman get the go-ahead from the Bayview tower to proceed, and at 1:16 they pull out of the yard.

To keep a freight train moving, an engineer is supposed to keep his left foot on the dead man’s pedal, a simple, floor-mounted safety device that has been around for along time. If the engineer becomes incapacitated and his foot leaves the pedal, the train stops.

Many engineers consider the dead man pedal a nuisance. It’s uncomfortable to keep your foot- on the same spot, sometimes for more than twelve hours at a stretch. You get leg cramps. You can’t get up from your seat, even to use the cab bathroom, without stopping the train.

The dead man’s pedal is probably the most commonly disabled safety device o na freight train, and any engineer will tell you it’s the easiest thing to do. All he has to do put a wrench on top of it.

Rick Gates’ s engine has a disabled dead man’s pedal, the throttle is set for acceleration, and no one has to steer a freight train For the time being this train doesn’t need him anymore.

Gates and Cromwell are not a regular team: the crews are always rotating. But they’ve spent enough time together to know they have something in common. They both like to get high.

And so they light up a joint.

They make some small talk. Cromwell is soft-spoken, when he speaks at all. Some of his past crew mates say it’s possible to spend twelve hours in the cab with him and new exchange a word. Off duty, he’s alway available for a pickup softball game, and he wields a pretty good bat. Most people who know him like him.

Gates is a rock music lover and a Star Trek fan who is more outgoing. He’s been running the rails for fourteen years, and in a job that is often boring, conversation helps keep him alert. He smokes four packs of cigarettes a day. He sometimes bring home-cooked meals to work to share with his crewmate on a job.

Mixing a demanding work schedule with a growing affection for alcohol didn’t help his marriage, and he and his wife, Mary, split up a few years ago. She kept custody of their wo daughters.

After the separation, Gates moved into a apartment in Essex and threw himself railroading. It seemed to define everything about him. He plunged into the rules and regulations, scoring high marks on his proficiency tests. He scored 100 percent on his last one.

Gates is proud of this knowledge and chides other engineers when they do something that’s not by the book. He cites the rulebook from memory.

He has been disciplined by Conrail for insubordination, and sometimes he plays his harmonica over the nighttime radio waves, which is definitely not allowed by the rules. Driving his car, he has racked up nineteen citations in fifteen years—mostly for speeding and twice has had his driver’s license revoked.

But his record on the rails is good, and of most of his colleagues are happy to have him as a crew mate. The consensus among those who know him in the railroad fraternity is that Gates is a railman with the right stuff.

But early on the afternoon of January 4, at the controls of Conrail train ENS-121, Lynn Gates is not altogether in character.

A marijuana high is different from the effects of alcohol or other drugs. It can distort one’s sense of time—a half-hour can feel like five minutes, or five minutes can feel like an hour.

In the past ear, Gates has taken a train through the Gunpow switch ninety-nine times, usually from Bayview. As with any familiar routine, he has developed a certain feeling, an internal clock, that tells him how much time he should elapse from step to step. Gates is used to moving long, heavy freights trains that can take ten miles to get up to speed. He is used to a fifteen- or twenty-minute lull between Bayview and Gunpow “distant signal,” two miles before the switch at the interlocking of the freight and passenger tracks.

But today Gates is running light engines, and he has fooled with the delicate workings of that internal clock.

Once out of Bayview, his three-engine train picks up speed much more quickly than the seasoned engineer is accustomed to. Twenty-four steel wheels race along the rails, clacking from joint to joint. The big engines whine as they suck up diesel fuel and the scenery rushes by. Conrail train ENS-121 hits 60 miles an hour less than a mile out of the yard, tens of thousands of feet sooner than would a train weighed down by freight.

Fifteen miles to the north, Edgewood Tower switching operator Richard Hafer is expecting the Conrail. But first he’s expecting a crowded Amtrak passenger train, streaking along at more than 100 miles an hour.

The dispatchers keep the radio chatter going: “Got a hot move coming for ya,” says John Akins at Perryville.

“Aaah, what are ya gonna wake me up this time of day for?” Hafer responds. ”It’s almost quittin’ time.”

“Fifteen will be coming three, eighty-one will be on four and, oh, I think we’ll double barrel them.”

”And let the engines sit at Gunpow?”

“Sure.”

“All right,” says Hafer, “we can handle that.”

Jerry Evans puts his love for his work into a poem in 1981:

I ride my magic carpet

On ribbons made of steel

And my heart keeps pace

To the tapping of the wheels

Over mountains and through valleys I glide on shiny rail

As the boxcars float behind me

Like the wind through a stallion ‘s tail

I am the mind, my hands are the nerves

As I pilot my carpet by the sea and around curves

The power is addictive.feelings immense But now my ride is over

Mommy, can I have ten more cents?

At 1:23 p.m. on January 4, Evans has just crossed the Baltimore city line. He lets the Amtrak train’s speed build to about 120 miles an hour. It’s supposed to be capped off at 105, because the Colonial today includes one of the older Heritage passenger cars, built in 1953 and not designed for the Northeast Corridor’s highest speeds. Amtrak’s express Metroliners, the fastest passenger trains in the country, routinely operate at 125 miles per hour. But the Colonial is not a Metro liner.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Some engineers stay away from passenger trains, because they can’t stand the man· date for high speed. Not Jerry Evans: He likes to go fast, just like any other engineer drawn to the high-speed Amtrak engines. To Evans, speed means control. In his auto, he’s earned eleven speeding tickets since 1969, though nothing alcohol-related, no reckless driving. Just speeding.

Evans and his colleagues are proud of their work and consider themselves no less professional than airline pilots. Their rail· road competes successfully for passengers with the airlines in the Northeast, claiming a 32-percent market share of the commuter traffic between Washington and New York. more than any one airline. But to maintain that share, speed is of the essence.

At the controls of the Colonial, Evans presses on. He didn’t have to work today. but took the extra duty for the $140 that will go to fixing up the house in Overlea. He’s missing the christening of his best friend’s little girl today and doesn’t feel good about that. But Denise will stand in for him at church.

Inside car 21236, the passengers have settled in comfortably. They have plenty of leg room and head room, open luggage racks overhead, no seat belts, a smooth ride, and the confidence that they’re using what they’ve been told is one of America’s safest ways to travel.

Conductor Donald Keasey comes through the car.

He takes a $29.50 ticket from a 16-year-old girl who wants to be an astronaut, an ambition that became unsettling to her mother after the space shuttle Challenger exploded.

Ceres Horn arrived home after classes at McDonogh school that day, Susan Horn’s eyes fixed on hers and the two rushed into a illg. “Precious,” her mother said, “I don’t want you to become an astronaut. I just couldn’t live with you coming into that kind of danger.”

But Ceres pulled away. “Mommy,” she said, “!can’t think of a better way to get to Coo than to be blown up to him.”

The conductor steadies himself from seat to seat as the train races on. He comes to Christy Johnson, who has unfinished business in California, where she’s helping a Palo Alto probation officer counsel a teenage drug abuser. Christy hands Kesey her I ticket.

He comes to TC Colley, who left a note the door of a dormitory buddy in Province—”I’m coming back. Are you?”—and who put down $58 for a train ticket that says he’II keep his pledge. Amtrak’s Colonial 94 rounds the sweeping curve that will bring into view the Gunpow switch, telling the crewmen to go even slower and to get ready to stop. They fly past it.

Moments later, at 1:29 p.m., Gates spots the “home” signal up ahead, 350 feet from the main line. Even through his oil-smeared windshield, the bleak winter sunlight paling the signal’s amber dots, he can make out what it says: Stop. That means the switch is closed, and that means something is probably coming on the other track—the high-speech passenger track.

The experienced engineer in Gates snaps to. Now fifteen hundred feet from where track meets track, he wants only to stop.

The throttle is cut and the emergency brakes are slammed on. The three engines jerk as the wheels lock and slide along the rails, squealing and spewing sparks. Gates and Cromwell are suddenly at war with more than three quarters of a million pounds of black and blue metal going 60 miles an hour.

The engines go through the closed switch, throwing it open and breaking into the main line. Gates and Cromwell find themselves sitting on the high-speed track, with part of their rearmost engine straddling the switch behind them.

Gates is breathing hard.

He and Cromwell know they’ re in a bad situation. They can’t turn right, can’t turn left. If something is coming behind them, they probably can’t outrun it. They might be able to back up, to go back over the switch, and the engineer throws the engine into reverse.

Cromwell looks back down the main-line track. He sees the powerful headlight of a train as it rounds the curve. He shouts over the din of the diesel engine:

“There’s something coming! Jump!”

Cromwell sprints away.

Alone in the cab of Colonial 94, Jerry Evans is doing what engineers normally do when the visibility is clear-focusing on the horizon, as far ahead as he can see, where the rails meet the sky. High-speed trains need a lot of room to stop.

The horror stories of veteran engineers spill out in taverns close by the railroad yards: kids who stand with their bicycles on the tracks until they can get the engineer to blow the horn; older kids who suspend manhole covers from overhead passes just to see what happens; teenagers in a car waving beer cans and pulling away a few seconds before the train comes by; one too many drivers trying to beat the train at a crossing. Engine–makers have given the cabs bulletproof windows, across which birds sometimes explode like balloons filled with red paint.

At night the engineers see a locomotive headlight in the distance and they’re not always sure it’s not on their own track. They can feel their hearts beating.

Despite the dangers, engineers don’t often get hurt. But rail men still talk about how the companies cut back on maintenance and safety employees, and the more conscientious worry about the drunks and druggies too. There has been a general feeling for some time now that the rent is well past due.

As for Jerry Evans, he’s a heavily invested family man, and he takes no chances. He lost his mother last fall, and it made him think about the fragility of his own life on the job. He wrote out a will and discussed his feelings with Denise in November. At first she didn’t want to hear about it, but Jerry said it was best to be safe, to worry about herself more than him in the event of an accident. “I wouldn’t know it,” he said. “It would happen that fast.”

Then he told her, ”If anything ever happens to me out there, don’t settle.”

In the cab of Colonial 94, Evans scans ahead as the Gunpow switch comes into sight around the curve.

A patch of Conrail blue occupies the place fifteen hundred feet ahead where his train is going.

He throws the Colonial into emergency at I :30 p.m. The braking will last fourteen seconds.

The passengers in car 21236 lurch slightly. Conductor Keasey has just finished collecting tickets in the first three cars and thinks to himself, “I wonder what Jerry’s doing up there.”

Harold Bergin, a chef from New York headed home after the holidays, look.s up from a magazine story about how to make risotto. He’s got his Walkman radio on and can’t hear the pair of skis rattling in one of the racks overhead. His wife, Kyra, continues reading her New York magazine.

In the locomotive, Jerry Evans is going through the moments that his wife will later be unable to shut out of her mind. She will wish that she could somehow have held him, to soothe the inescapable terror.

Evans does not jump from the cab; it probably wouldn’t matter if he did. The physical pain is gone in milliseconds. The poet with the boyish passion for trains will be eulogized as ”the best darn engineer.”

Northeast Corridor radio traffic, 1:31 p.m., January 4:

“Just talkin’ about somebody in emergency here. Just a minute.”

“Ya hear that, Power Director?”

“1 SL, 2SL Perryville?”

“Yeah, what is it?”

“Transmission.”

“We just lost power.”

“He lost the transmission line.”

“Oh, shit.”

“What happened?”

“Those engines went through the signal at Gunpow. They said that and, ah, 94 got into them. We need ambulances at Gunpow. Right here at the interlocking, evidently.”

“He hit ’em.”

“He sure did.”

A fireball mushrooms at the point of impact. Harold Bergin is thrown forward and sees a bright orange light filling his window. He shouts to Kyra: “Hold on!”

The Colonial has slammed into the side of the rearmost Conrail engine straddling the switch and the main track. The lead Amtrak engine disintegrates and the Conrail locomotive explodes into countless pieces, the largest a chunk of scorched metal the size of a motorcycle. Thousands of gallons of diesel fuel are ignited.

Almost a quarter mile south of the switch, the Colonial’s rear cars continue forward, shoving the forward cars off the track in a zigzag chain reaction. For ten seconds the entire crumpling mass slides forward along the tracks.

Cromwell is running for his life, cringing under a canopy of shrapnel flying all around him. One piece fractures his lower leg and drops him to the ground. He gets up and keeps running.

The empty cafe car behind the Amtrak engines is heaved on its side and slams to the ground, scraping along the rails. The next car, 21236, also flips sideways. Bergin watches the ground passing by the window as thunder envelops everything, muffling the screams. Seats break free and tumble everywhere. Luggage and people fly. Bergin is hurled forward more than ten feet into the aisle, stopping when his head hits a seatback.

The front of the car corkscrews, its thin aluminum skin ripping into huge, jagged blades. It cracks and buckles as the mass of burning wreckage slows and finally stops.

The first thing Bergin can’t figure out is why he can’t hear screaming and crying. He doesn’t know that half the people who have shared his car are dying and others are unconscious.

“Harold?” It’s his wife calling.

“Kyra?”

They can’t see each other because of the gathering black smoke of the diesel fuel and the twisted heap of luggage and chairs. He has lost his glasses, and she has blood dripping into her eyes.

”Find your way out,” says Harold. ‘T find my way out. Just get out.”

Kyra gets out through a window a drops shoeless to the cold, sharp gravel. She takes in the scene, how the network of overhead wires is tangled around the wreck—a huge, battered insect in a broken web.

Harold is in one end of the car and doesn’t see many signs of life. He climbs back and forth, desperately looking for an escape. His only route is partially blocked by a man who is pinned to the floor, alive and conscious. Harold has an injured left shoulder and cannot free him. The thought of just climbing over the man and leaving him is sickening, but there’s no other way to go. Harold apologizes as he clambers over the man to safety.

The Bergins try to get their bearings. Other passengers already are milling around, some moving purposelessly in shock. As the Bergins huddle together and the cold air tightens the blood on their faces, they look across a drainage ditch to see the gathering people of Chase looking back at them—each side staring in stunned disbelief, two groups of people jerked from the routine of a Sunday afternoon.

Some of the Chase residents are crying. Finally one woman shouts, ”Does anybody want to use my telephone to call their families?”

Reality comes to Rick Gates in pieces, an escalating image of catastrophe that his mind tries its best to deny. At first he clings to the hope that no one was killed. He’s worried about Butch, because he didn’t see where he went. He has no idea what happened to the Amtrak engineer—who he would later learn was someone he’d passed many hours with when they both worked for Conrail.

As the black smoke billows from the heart of the wreckage, Gates runs back the largely intact Conrail lead engine, which was pushed nine hundred feet up tracks and away from the wreck. He keys the portable radio and shouts “Emergency emergency, emergency!” He shouts it repeatedly but can’t seem to raise an answer from any of the area towers.

He grabs a fire extinguisher and runs back to where some of the cars have piled onto the back of an Amtrak engine, which is crushed into the trackbed with one car elbowed over it, and there Rick Gates is confronted with his first casualty. A man pinned between the engine and the top car moving his head and moaning as the fire creeps toward him. Gates chips away at flames with the fire extinguisher as emergency workers show up. The man is spared from the flames, but will die a few hours later.

Gates races back and forth around t wreckage. People who know him begin arriving, members of railroading’s extend family who happen to live nearby. Former Conrail engineer Pat Kelly finds him pumping the radio for help. Gates gives him the radio and Kelly asks what happened.

“I blew a red,” says Gates. “I got through a switch and I couldn’t get back.”

Gates goes looking for Butch, who by now is calling his girlfriend, who also lives nearby. Cromwell tells her he’s okay and adds, “I think I’m going to lose my job.”

A Conrail conductor and his wife walk to the scene at about 1:45, the wife thinking to herself, “This can’t be real. Whoever did the special effects in this movie is going win an Oscar.” As George and Harriett Telljohn come upon their friend Rick Gates, he is pacing around frantically in his oversize brown leather flight jacket, holding on to the receding hope that no one has died.

The Telljohns assume that Gates has also just arrived. “Rick, what are you doing here?” asks George, who will remain Gates’s close friend right through the worst of what is to come. “How’d you get here so fast?”

“l was the engineer,” says Gates. Butch was with me. Go find Butch.” Telljohn goes looking for Cromwell. Harriett Telljohn and Gates remain talking as rescue workers walk by with a stretcher bearing a lifeless human form beneath a white sheet. It passes two feet from the engineer, who shudders. He then overhears a fireman’s orders to another rescue worker. “There’s another one over there in the bushes. Go get it.”

“Oh my God,” says Gates, falling into Harriett’s arms and sobbing.

He hears cries for help and comes upon a woman in her 30s, trapped between the end of the car and a seat that has her pinned to the floor. He tries to free the seat but it’s pressured in. In moments he will be joined by the first two police officers on the scene. They finally will free the woman after about an hour, when the accident scene has grown into an enormous and complex emergency operation.

A total of 507 fire fighters with 135 pieces of equipment have responded; 509 county police, 185 state police, and sixty Amtrak police; two hundred Red Cross workers and hundreds of other volunteers and medical personnel. And 619 residents of Chase who get involved will later participate in a survey by county police. During the next few hours, the rescue forces set up command posts, aid stations, and staging areas for transporting the injured.

The first ambulances to arrive are raided by panic-stricken survivors who loot them of tape, gauze, first-aid kits, anything they can reach. In all, 175 passengers will be listed as injured in the crash.

This is not the first transportation disaster to visit the Chase peninsula. Some of the locals remember when a Capital Airline prop plane carrying thirty-one people exploded in a storm in 1959 with no survivors. But it’s different when there are so many walking wounded, and the people of Chase are responding in a hundred ways. Two boys are the first of more than thirty local volunteers who go into the cars and carry out the injured. Two paramedics cannot stop crying. Seventeen-year-old Michael Booker is unnerved by the limp body of an infant in his arms. He later will learn that the child survived.

Neighbors bring out blankets and first-aid supplies. One man works his backyard garden hose on a spreading brush fire. A few young men place lawn chairs on the roof of a nearby garage and eat dinner while they watch.

Still others whose houses are clustered along the tracks bring survivors inside, offering blankets, coffee, telephones. Their homes are transformed into communications centers, first-aid centers, bases for reporters and photographers. Some houses are thoroughly trashed: bloodstained floors, carpets thick with mud. The county will later solicit requests for reimbursement.

On the other side of car 21236 from where Waskevitz still is working, rescue and trauma workers are struggling to save three people trapped in the compacted maze of steel. At least two other people are trapped and still alive there.

Dr. Ameen Ramzy of University Hospital’s Shock Trauma Unit is accustomed to seeing seriously injured people hanging at the edge of their mortality, and he has brought many of them back. He worked in a Beirut war zone a few years ago. But nothing has prepared him for the daylong succession of disappointment he is about to through. Of the fifteen passengers of Colonial who are killed, thirteen are aboard car 21236.

The trapped victims are really trapped The powerful “jaws of life” rescue device is like hand pliers against the train’s heavy steel. If the doctor can get some of the victims intubated with fluids, he can prolong their chances for life. But some of them are nearly impossible to reach.

Essex paramedic Kathy Smith is tending to a 7-year-old boy and his grandmother who are trapped together in one end of the top car. Adam Moore—a budding young model from New Jersey with a face that some photographers fawn over—is pinned on one side by a buckled seatback, and on yet another by one wall of the car.

“Let me out of here,” Adam pleads with the paramedic. “Why don’t you help me?”

“Hush, baby,” says 52-year-old Peggy Moore weakly, “They’re trying to help.”

“I want to go home,” says Adam.

“We’re going to have you out,” the paramedic assures him. “It won’t be too much longer and you’II be headed home.”

“Do I have to go by train?” he asks. Just then a stream of cold fire-suppression foam pours into the car from firefighters working on the outside. It forms a pool around Adam, and the paramedic can’t protect him from it. Now Smith has to worry about hypothermia.

She urges doctors in the Shock Trauma “Go” team to consider amputating the grandmother’s legs as a last-ditch effort to save both victims.

The doctors aren’t so sure it’ll work. Smith gets frustrated as the Moores grow weaker with the passing minutes. She turns to another paramedic, “What are they waiting for?”

As doctors hook up IV lines and firefighters struggle with seemingly immovable steel, both the 7-year-old and his grandmother drift in and out of consciousness before finally slipping away-within minutes of each other.

When a ‘Go’ team doctor pronounces Adam dead, one paramedic stares up at him and says, “Doc, are you sure?”

Nearby, one woman is extricated alive and flown to the trauma unit, where her legs are amputated. She lingers for eight days before dying.

Outside the top car, a doctor is stopped by a man with a slight injury to his face. He says he would like to leave the scene, but would the doctor mind certifying his injury? ‘I’m sure my lawyer will be mad at me later if I don’t get one now,” he says.

The National Guard erects a large canvas tent—a morgue.

By nightfall, County Police Chief Cornelius Behan turns to Major Robert Oatman and says, ”Keep in mind that this could turn into a criminal investigation.” Oatman seals off the area around the Conrail engines up the track. But by this time a number of people, including Rick Gates, have been in and out of the cab. The cab is now clean. Gates’s and Cromwell’s belongings are soon returned to them unexamined by police.

A cleaned-out cab will later add fuel to rumors that the Conrail operators were watching the playoff game on a portable television on the job, and that someone later threw the set into the nearby river. But county police skin divers will search the riverbed without success.

As rescue efforts continue, federal investigators clamber through the wreckage. Some of what they find leads them back to the cab of the Conrail locomotive at hundreds of feet up the track, and some what they find will lead them far beyond.

Susan Horn hears of the wreck over the car radio on her way home from Penn Station and immediately starts talking with God: “Please don’t let that be her train.” Her 9-year-old boy remains unwaveringly optimistic. “Mommy,” says Howie. “I know she’s all right.”

At home, they guard the telephone and monitor the television. Early in the evening, Susan calls her husband in Haifa, Israel—”Roger, it’s bad news. There’s been a train crash with Cere’s train. It’s been hours and we haven’t heard a word. We have to assume that at best she’s been very seriously hurt.” Roger Horn is given an immediate “compassionate case” seat by El Al on at flight to New York. He will spend the thirteen-hour flight trying to assume the best, his stomach twisted into a knot.

The Horns hear nothing until after dawn, when a family friend goes to the temporary morgue at the crash site and finds Cere’s body.

Susan, Corinne, and Howard huddle together for strength on Monday. Roger calls from Kennedy Airport in New York that evening. He tells them, “I love you. There’s a lot of love in our family and it will get us all through this.” In Potomac, Arthur and Ann Johnson spend the early hours calling for information, the looming silence giving them no comfort.

They call their daughter who Joy in New York, who reminds them of Christy’s recent paramedical training. “She’s probably just treating people at the scene.” By 4:30 a.m. Monday, they have joined other relatives of Colonial passengers at a Holiday Inn about twenty miles south of the wreck. All they are told is “stand by.”

Ann Johnson is reading the Psalms in her Bible-the 23rd, the 51st, the 88th, “O Lord, I call for help by day; I cry out in the light before thee.”—and she hears them as if at a funeral. An Episcopal minister approaches them at midmorning, accompanied by a couple of police detectives, a Red Cross worker, and an Amtrak claims agent. Gently they confirm the worst. One of them thinks to warn the Johnsons of the cluster of media people waiting in the lobby. Arthur turns away and says, “Somebody find me a back door.”

In Pennsylvania, Tom and Susan Colley have kept vigil throughout the night, anxious about using the phone for fear they’d block their son’s incoming call. They’ve been through this routine before. A year ago, TC was in an Amtrak train that hit a truck south of Chicago. Lots of cars were knocked off the track, but nobody was seriously hurt. That’s always comforted them about taking the train rather than flying: so many fewer passengers would have survived an airplane crash.

At the time, Red Cross got TC to a phone to call his parents in the middle of the night. And as time went on, whatever trauma he had experienced was transformed into a remembered adventure. So the Colleys figure TC might just be unimpressed with such familiar territory and maybe has caught one of the buses provided by Amtrak.

Then an incoming phone call puts an end to that hope, and Tom Colley finds himself notifying other relatives that the sole heir to the family name has been undone.

In the coming months, he will spend many hours in the photographic darkroom he shared with TC, printing his son’s previously unprinted photos, dwelling on the unfulfilled promise of a remarkable talent.

Gates and Cromwell soon reestablish contact. Aware of the mounting search for guilty parties, they decide to lie. The first rumors from the investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board hint at switcher error. But these pass as investigators talk with people who talked with Gates just after the crash, one of whom quotes him as saying, “It’s pretty obvious what happened. I got through a red and couldn’t get back.”

At 1 p.m. on Wednesday, as workers continue to clear debris from the site of the wreck, Gates is sitting in a lawyer’s office in Baltimore, surrounded by lawyers, federal investigators, and a few union men.

He is telling them what happened after Bayview: …from there we continued north, received clear indication on the home signal at North Point, a clear signal on the home signal at River. . . We received a clear signal on the 836 signal at Bengies, and then at the 816 signal. At that time, Mr. Cromwell was fixing his lunch, and cutting open some water bottles, so that we could put our Cokes into. And I saw the ‘approach limited’ signal flashing—had to get right close to see it, but it was flashing. And upon going under it I called the ‘approach medium’ signal to Mr. Cromwell. He turned around, and I don’t know whether he saw it or not, but he saw the ‘approach medium’ in the cab. I acknowledged as we went under it and started slow down a little bit. Mr. Cromwell and myself were talking, and as he fixed his lunch we were basically complaining about the engines. And after that—I don’t remember how close I was to the stop signal, but as soon as I saw it I immediately dumped the air, plugged the engines by putting reverse in reverse and pulling back on the throttle again. I grabbed the portable radio and started yelling the emergency. And after that we—that’s when the accident happened.

They ask him about the alert or whistle. “I acknowledged it so fast it didn’t have a chance to go off,” he says. They ask him if was on drugs the day of the crash. He tells them no. They ask if he is a user of alcohol or drugs. After an interruption from his lawyer, he tells them, “Upon advice of my counsel, I will not answer that.”

Then it’s the brakeman’s turn. Cromwell says he helped Gates monitor a steady succession of clear signals on the way to Gunpow, when he took a break to prepare a sandwich and some drinks. He says he never heard an alert or whistle, and that he wasn’t looking when the train approached home signal at Gunpow: The next thing I remember is I was still in process of getting my sandwich-—everything all set after we went by the Chase signal—it’s the 816—and I don’t know how long after that, but I heard the engine jump. The engines jumped. I didn’t know if Rick did it, or if it was some kind of failure or deraling or what. So I looked out the fireman’s side windows, and I seen the headlight in back of me. I didn’t know if the light was stopped, moving, or you know, what it was doing. . . .

After the crash, an ambulance took him to Johns Hopkins Hospital for his broken leg, and later Sunday he gave blood and urine specimens. He goes on to say that he hadn’t used drugs that day.

Two federal drug labs, however, will say that he had-both marijuana and PCP, a particularly powerful drug sold as an animal tranquilizer.

Evidence of marijuana use also was found in blood and urine samples taken from Gates the evening of the crash.

Gates’s and Cromwell’s statements are the last they will make publicly before a shroud of silence descends over their actions in the cab.

Both hide from the press. Gates resorts to waiting in the laundry room of his apartment building until the TV cameramen have left his door. He spends days and sleepless nights alternating between guilt and denial. One night in February his friend George Telljohn finds him sitting on his couch with a pile of mail, mostly hate mail, on the coffee table. Gates hands one letter to Telljohn, not lifting his gaze from the floor. A snapshot of Ceres Horn flutters to the table. The letter reads:

Dear Mr. Gates,

You don ‘t even know me, but your life has had such a significant impact upon mine. I am Corinne Horn, sister of Ceres Horn, victim of the Amtrak crash.

I don’t know if you read the newspaper articles on my sister, but if you did, you would know that she was a 16-year-old freshman at Princeton who was ranked second in her senior class, and graduated Magna Cum Laude from McDonogh School. . .

She was absolutely the best person, besides my parents, to ever set foot on this earth . … Reese was my better half. When I was flirting, she was studying or doing something constructive. Reese was going to bean astronaut, her childhood fantasy. And then you shot her down.

Mr. Gates, I bet you never dreamed of the consequences when you started puffing away on January 4, 1987. What could possibly have possessed you to smoke it on the job? I would understand if it was in the privacy of your own home, but not on the job.

I used to hate you/or killing the only person who ever fully understood me, who could identify with me. But not any more. Now I only pity you, because you will have to live every day/or the rest of your life with the knowledge that you took sixteen lives, sixteen beautiful lives . … I truly pity you, Mr. Gates, and hope that you are strong enough to face the days ahead, because I know I wouldn’t be.

Please write back to me. You owe me at least that much.

Telljohn asks Gates if he’II write back. Gates says his lawyers won’t let him. He soon goes to a psychiatric hospital for drug and alcohol treatment. He attends Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. He preaches about the perils of substance abuse to his friends, some of whom find his self-accusation unsettling.

“If Rick’s an alcoholic,” says one of his drinking buddies from the yard, “then I’m an alcoholic. And I’m not an alcoholic.”

While maintaining his claim that bad signals and equipment are to blame for the accident, Gates also tells at least one friend of his growing desire to become a substance abuse counselor. Some crash victims’ families, virtually all of whom would like to see stiff retribution, think that would be a very good idea. Already, however, the credibility of Gates and Cromwell—the two key witnesses to the crash—is diminishing. The evidence of their drug use and word of the taped whistle come to light. The Conrail engine’s speed recorder shows that it hadn’t slowed to the 40 miles an hour required by the signal that Gates had acknowledged seeing. A reenactment shows that if Gates had obeyed that signal, he would have been able to stop in time.

In the last 10 years, the American railway labor force has been reduced almost by half. Some in the rank and file blame this for fostering an attitude of rebellion against company policies and for reinforcing the traditional spirit of ‘us versus them.”

Amtrak’s worst crash is not the first to be used as ammunition by the bitterly feuding factions of the rail industry. The tragedy briefly held the promise of uniting them in common cause, but that promise is lost in a round of familiar accusations.

As the Federal Railroad Administration and the National Transportation Safety Board begin closing in on a conclusion of human error, some union men continue backing up Gates’ s story. “I don’t have any reason not to believe him,” says United Transportation Union representative Bill Packer in June. By July, Packer stops responding to inquiries.

After the discovery of the taped whistle in Gates’s cab, FRA Administrator John Riley announces a dragnet of the five major rail-yards on the Northeast Corridor. Despite the advance notice, federal inspectors discover six locomotives with identically taped whistles just two weeks after the crash. Later they will find seventy more across the country. Riley calls each one an accident waiting to happen. The unions ask where the FRA inspectors were before the accident.

“I think all of us heard stories at one time or another about engineers disabling whistles,” says Riley from his office on the eighth floor of the Department of Transpormion building in Washington. “But we didn’t know how big of a deal it was until Chase.The perception was that you couldn’t ever catch it, because it was so easy to cover up. You not only have to find somebody who is reckless, you also have to find somebody who is stupid.” When inspectors found a cab without a working whistle, he says, “We weren’t cailing them ‘tampering,’ they showed up ‘inoperative whistle’—just like any other mechanical defect.”

Amtrak president Graham Claytor points that the federal government is not responsible for the detailed inspection and maintenance of privately owned locomotives. “The [Conrail] management are the ones supposed to have caught that,” he says, “not the FRA.”

Labor leaders call Riley a front man for railroad companies and tell him to stay off their turf and to levy heavier fines on management violations. They say most safety problems stem from management’s squeezing every dime: deferring maintenance, pushing schedules, overloading freight cars. Riley calls railroad workers honest and hard-working but calls their union leaders “featherbedders.” In any case, he says, “I’ve offended everybody—which is as it should be.”

Riley wants the FR to have the same authority over railroad engineers—who are required to be licensed—as the Federal Aviation Administration has over airline pilots. He has no enforcement power over individual railroad employees. It is against federal law for an engineer to be drunk, but even if Riley personally found one with a six-pack in the cab of an engine, he couldn’t fire or fine them. Meanwhile, the credibility of the railroads’ new self-policing and drug-amnesty programs is called into question.

From almost every sector of the industry comes a call for mandatory random drug testing. But the unions insist that such testing is not constitutional. Proponents say that train operators should be held to a higher standard than others, and that only drug abusers have anything to fear. Labor counters that management could use the tests to harass employees. Proponents say computer-generated random selection would prevent that. But union officials respond to their constituencies by trying to shout down random testing at hearing after hearing.

In public they lash out at the companies and the regulators before more gently censuring some of their own, even as a few privately admit that nothing else has prevented on-the-job drug abuse, and that their own credibility is harmed. Riley accuses the unions of sacrificing safety by using the random drug testing issue as a bargaining chip. “They could help us a lot on safety,” he says, “but the price of cooperation is always ‘alcohol and drug’. lt ain’t gonna happen.”

In the months after the crash, many of the railmen’s taverns on the Northeast Corridor note a substantial drop in business. Predictions are that it will bounce back. In March a Conrail freight train overruns a “stop” signal just before a track junction near Philadelphia, with an Amtrak Colonial following behind. Automatic signals warn the Amtrak engineer, and he is able to stop his train well before the switch. The Conrail engineer is drug-tested and found to have marijuana metabolites in his blood at five times the level found in Rick Gates’s . In September a Conrail brakeman in the Bayview Yard—one place where it’d seem self-policing would be working well—faces his fourth charge of driving while impaired by alcohol. He has twenty-six prior traffic I convictions and six license suspensions or revocations. His drinking habit is no secret in the yard. He is still working on the railroad. Amtrak comes out in support of random drug testing, but Conrail opposes it, saying that its program of “reasonable cause” testing is good enough.

Several months after the crash, legal maneuvers leave Rick Gates more isolated than ever. He and Cromwell have been forced to resign their jobs, and Conrail stops paying for their legal defense.

Baltimore County state’s attorneys find a statute that would allow an engineer to be charged with manslaughter if the state can prove gross negligence. They subpoena Ed Cromwell, the brakeman who has become invisible even to the extended family of railroading.

In a meeting, they convince Cromwell and his lawyer that under state law any man in the cab can be indicted and convicted of manslaughter.

The defense attorney and his client decide to make a deal if state and federal prosecutors promise immunity from prosecution, in writing. The deal is made. Cromwell will testify in secret before a grand jury, and he will tell of the marijuana, missed signals, the cover story—everything.

The manslaughter indictment of Rick Gates arrives on May 4. The accused appears in public for the first time since the crash wearing mirrored sunglasses as his lawyer denies charges that his client killed sixteen people with a runaway train. Gates is in court for preliminary motions twice during the summer, each time sitting stiffly, with a thousand-yard stare, as his team of public defenders whisper among themselves. rarely turning to their client.

Roger Horn is there, wrestling with his feelings of pity for the accused and bitterness over the loss of the daughter he called his “best friend.” Susan Horn stays home, declaring her sympathy for Gates and Cromwell but adding that part of their punishment should be to have to live with a victim’s family for a week.

In considered moments, some of the victims’ families say that they know the crew never meant to harm anyone, and that they certainly must be suffering, too.

Railmen at the Bayview Yard take up a collection for Gates, in part to help him his child-support payments. Thirteen friends have pitched in to make his $5,000 bail. There is no serious discussion of helping Cromwell. They know he is working with the state.

Gates shows no anger toward the brakeman. He asks a friend how Butch is doing.

“Why should you care about Butch?”

“I pray for him every day,” says Gates, startling the friend, who thought he was an agnostic.

“Even though he supplied the drugs and then worked for the state so he could get off scot-free?”

”All the more reason to pray for him,” says Gates.

Stated in its most basic form, the cause of the accident was the failure of Amtrak No. 94 to stop before striking Conrail ENS-121. —Conrail’s “proposed probable cause.”submitted to the NTSB.

At the congressional rail-safety hearinq on that hot Thursday in July, Tom Luken, chairman of a House transportation sub-committee, is grilling the FRA’s John Riley about the industry’s safety record. The crash of the Colonial is the biggest nightmare of Riley’s four-year stint.

Riley sips his water as he parries the Ohio Democrat’s pointed questioning. He produces charts and graphs of what he calls improved safety statistics.

“Now these figures are impressive,” responds Luken, “but are they possibly misleading?”

A union man cannot stifle a guffaw. Labor leaders are grouped on one side of the room, enjoying Riley’s discomfiture.

It’s said that some Conrail officials are here, too. Their company moves more freight than any other in the region, but since January 4 its public presence has been conspicuously scarce.

Amtrak’s Graham Claytor testifies that there’s no need to increase the fines for management safety violations because mere citations are insult enough. Anyway, he points out, in fining the heavily subsidized Amtrak, the federal government would be, in effect, fining itself.

All the while, Roger Horn the parent.sits on the floor in the lee of the half-wall separating the constituents from the politicians

Sometimes he asks himself, “Why am l doing this? Why is it up to the wounded citizen to do what these people are paid to do?” He thought he could protect his family from a dangerous world. Safety was a first priority. He has never allowed his children in cars driven by teenagers. The Horns held an alcohol-free party for Ceres’s senior prom. Now, he says, he feels “stripped of my manhood” by forces beyond his control.

He finds himself wanting to stand and shout, ”Gentlemen, this is not an academic exercise! These are real people and events, and it’s going to happen again!”

By 4:30 p.m., there are fewer than half a dozen spectators left in the once-jammed hearing room. It’s time for Roger Horn and Tom Colley and Arthur Johnson to testify. They gather at the witness table.

Johnson is a former administrator at the: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and a veteran of congressional hearings. His daughter Christy was crushed and suffocated in the wreck of the Colonial 94. ”On several occasions I have listened in amazement and disgust to representatives of labor and other lobbying bodies as they consistently resist efforts to strengthen the law, even though their own members would be the first to benefit,” he says.

Luken then leaves, explaining that he must catch a plane back home. Now only one congressman is left in the room.

Colley testifies in the nearly empty room. The bearded professor of theatre from Shippensburg University speaks om a calm but impassioned voice about how his 18-year-old son, TC, was burned before dying of smoke inhilation. TC was his only child, the fourth Colley to be named Thomas, the one who promised to name his own son Thomas.

Now it is Roger Horn’s turn. Traces of emotion slip into his otherwise academic delivery. Before reading a statement, he brings up the idea of “jail time for egregious negligence” on the part of railroad company executives. “That will get their attention.”

In his statement, he urges Congress to pass a tough rail-safety bill. “We have leaned to our horror,” he adds. “that neither the railroad companies nor the railroad companies nor the railroad unions will voluntarily enforce appropriate levels of operating safety, not even those railroad companies that are actually creatures of the federal government.”

The victims’ families linger in the hallway. They share their frustrations, their disgust at the day long display of self-preservation in the wake of such needless human destruction.

They’ve watched as each party used the tragedy for its own designs. The actions of the two Conrail crewmen made it the perfect case for we-told-you-so’s from company management and the FRA. Equipment problems like the lack of automatic train control and untested safety whistles served the same purpose for labor. ”Watch out,” said a labor lawyer in passing. ”There are more crashes coming.”

The families are angered by Conrail’s absence from the public process. They give Amtrak’s Claytor credit for facing the heat, even if they aren’t happy with many of his answers.

Some progress has been made. The FRA proposed phasing in ATCs on every train in the Northeast Corridor over two years. Conrail says the government should pay for ATCs on its locomotives. Amtrak agreed to install prototype luggage-restraint systems on four cars and to equip the rest of the fleet if they work. Amtrak and Conrail already had agreed to reduce freight-train presence on the high-speed rails.

Horn and the Colleys are car-pooling back north in Washington’s rush-hour traffic, wondering aloud how to assign blame.

They’ve heard about how the operators of the errant Conrail engine had used drugs; how federal inspectors had failed to monitor a growing problem of disabled safety devices; how the FRA and the NTSB had temporarily pursued, and with Amtrak’s blessings then dropped, the case for automatic train controls; and how labor continues to fight against federal licensing and random drug testing of crewmen.

Roger Horn falls silent for a time, until the traffic comes to a standstill. “There’s enough blood to go around for everybody,” he says.