More than 300 North American bird species will lose more than half of their current geographic range in the next 65 years, according to a study published Wednesday.

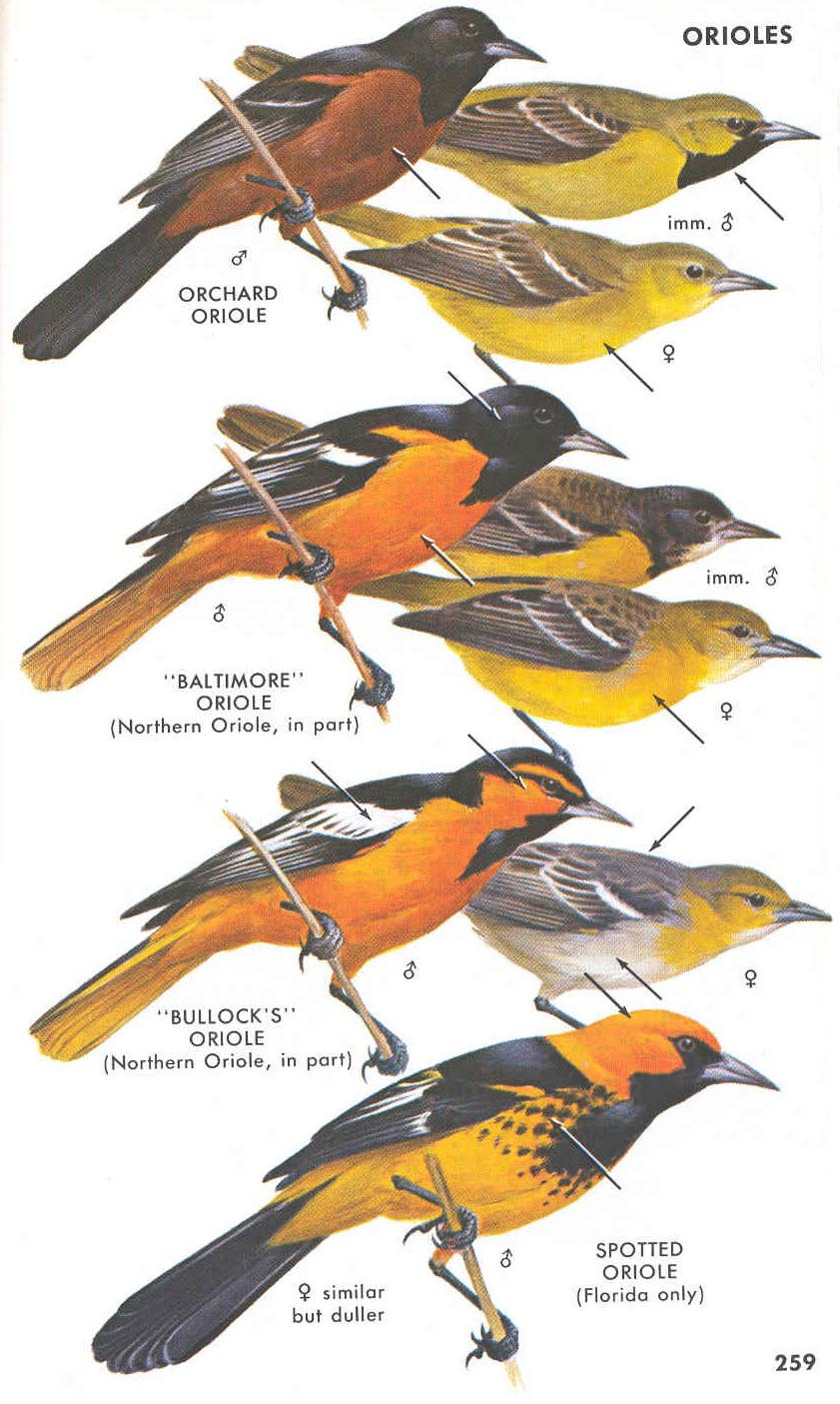

In some cases, North American birds are projected to lose almost 100 percent of their suitable habit. For other species, including Maryland’s beloved Baltimore oriole, the loss of their habitat range from rising temperatures will push birds into new replacement geographic areas.

The report, “Conservation Status of North American Birds in the Face of Future Climate Change,” published in PLOS ONE, a peer-reviewed, open access scientific journal, concluded that even under the most optimistic scenario, warming temperatures will generate major shifts in species’ habitat ranges.

“The Baltimore Oriole, state bird of Maryland and mascot for Baltimore’s baseball team, may no longer nest in the Mid-Atlantic, shifting north instead to follow the climatic conditions it requires,” lead author Gary Langham, chief scientist of the National Audubon Society, told InsideClimate News, a web-based, 2013 Pulitzer-prize winning, nonprofit organization.

The Baltimore oriole was named for the resemblance of its colors to Lord Baltimore’s coat of arms. It breeds across much of the northeastern U.S. and Canada and migrates as far south as the Mexican border.

Other birds may have it worse, however, Langham noted.

“It wasn’t as if the ranges were just shifting [for some species in the models] but rather they were just disappearing, almost the way you think about species on a mountaintop being pushed further and further up the top of a mountain.”

The Baltimore oriole’s habitat range below in 2000 and as projected by 2080 by researchers is illustrated in the following graphic:

Langham and his team of National Audubon Society-affiliated researchers used 30 years of climate data and the North American Breeding Bird Survey and Audubon Christmas Bird Count—two of the most long-running and comprehensive continental datasets of vertebrates in the world—in compiling the study. They modeled and assessed geographic range shifts for 588 North American bird species during both the breeding and non-breeding seasons under a range of future emission scenarios.

“The persistence of many North American birds will depend on their ability to colonize climatically suitable areas outside of current ranges and management actions that target climate adaptation,” researchers stated. The study was funded in part by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Other iconic birds threatened in the coming decades include the bald eagle—the population of which has been successfully re-introduced in Maryland following near-extinction—and the state birds of Louisiana (brown pelican), Minnesota (common loon), Vermont (hermit thrush), Idaho and Nevada (mountain bluebird), Pennsylvania (ruffed grouse), New Hampshire (purple finch) and Washington, D.C. (Wood Thrush).

An interactive map exploring the Baltimore oriole and more birds around the country threatened by climate change can be found here.

“The prospect of such staggering loss is horrific, but we can build a bridge to the future for America’s birds,” said Audubon president and CEO David Yarnold in a press release following the study’s conclusion. “This report is a roadmap, and it’s telling us two big things: We have to preserve and protect the places birds live, and we have to work together to reduce the severity of global warming.”