hortly After 10 o'clock on the night of April 14, 1865, the celebrated actor John Wilkes Booth pulled off the most dramatic stage entrance of his short theatrical life. The play onstage at Washington, D.C.’s, Ford’s Theatre was the crowd-pleasing culture-clash comedy Our American Cousin starring British leading lady Laura Keene. Keene, however, was offstage then, ceding the spotlight to her co-star Harry Hawk, who was playing the titular cousin—an unsophisticated American who had come to claim his inheritance from his English relatives. Alone on stage, Hawk unleashed one of the play’s surefire laugh lines. “Don’t know the manners of good society, eh? Well, I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal—you sockdologizing old man-trap.” As expected, the audience of approximately 1,700 roared. Next came a loud bang, followed by a commotion in the private box at stage left where President Lincoln and his guests were watching the play. And then, displaying the daring athleticism that had earned him a reputation as one of America’s most exciting young actors, Booth vaulted over the box’s balustrade and dropped 12 feet to the stage below, catching his foot on the bunting decorating the box and breaking his left leg on the landing. Ever the consummate showman, Booth did not let whatever pain he felt prevent him from hitting his mark. He rose and moved to center stage where, lifting his dagger above his head, he cried, “Sic semper tyrannis!” a phrase supposedly uttered by Brutus during the assassination of Julius Caesar. It means “thus always to tyrants.” Moving assuredly through the familiar theater, Booth exited upstage right and slipped out the back door to his waiting horse before disappearing into the foggy spring night.

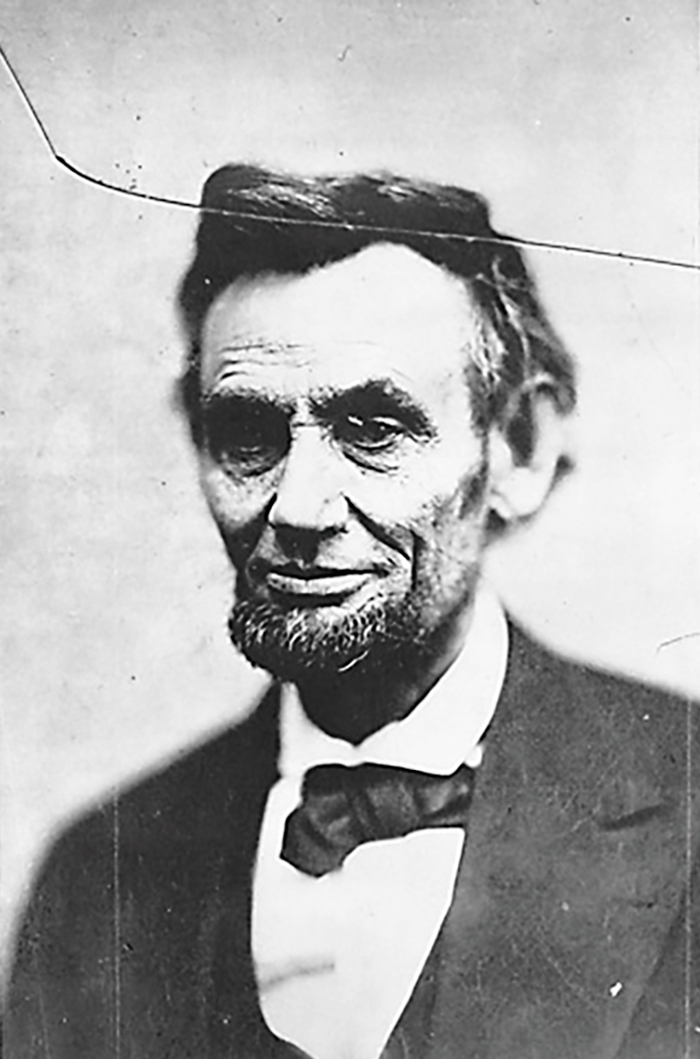

John Wilkes Booth had just shot President Abraham Lincoln. When Lincoln finally expired at 7:22 the next morning, Booth became America’s first presidential assassin. Even during a time of extraordinary upheaval, after four years of civil war in which roughly two percent of the population was killed, Booth’s act shocked the nation.

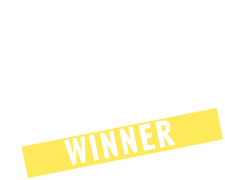

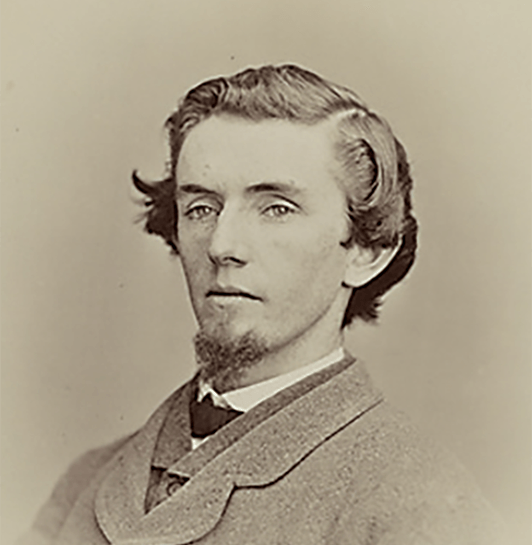

John Wilkes Booth poses at the height of his acting career.

Partly it was the novelty of the act. No one had ever succeeded in killing a president before, and many naively believed no one ever would. And partly it was because of who had done it. Booth was a member of a famed acting dynasty from Maryland that included his father Junius Brutus Sr., his older brothers June and Edwin, and various in-laws. At 26 years old, with what we would today call “movie-star good looks” and an easy swagger, Booth was the heartthrob of his day. Imagine a young Matthew McConaughey shooting Obama and you’re in the ballpark.

It was a deeply strange event for the public, and it retains its strangeness even now, 150 years since. However odd it was for the public, it was even more shocking for those who knew Booth. When a biographer was researching the Booth family in the 1930s, he interviewed Elijah Whistler, an old classmate of the assassin’s, who, even then, couldn’t reconcile the boy he knew with the man who had shot Lincoln in the back of the head at point-blank range.

“Everybody was stunned—couldn’t believe Booth would do such a thing,” Whistler said, adding that, far from the deranged villain of public imagination,

“Johnnie was kind and gentle.” This sentiment is echoed again and again in accounts of Booth from those who knew him best: “Warm,” “magnetic,” “generous,”

and “lovable” are adjectives that recur. But he could also be “moody,” “erratic,” “impetuous,” and “stubborn.” He was a man who loved animals and children,

who rescued a katydid from certain death in his sister’s insect collection but who, during adolescence, practiced marksmanship on neighborhood cats; a man

who offered to protect an African-American servant during the New York City draft riots of 1863, but who was incited to murder by the thought of “nigger

citizenship;” a man who decried the extremism he felt was tearing the country apart, but became a dangerous radical himself. Twenty-five years after the

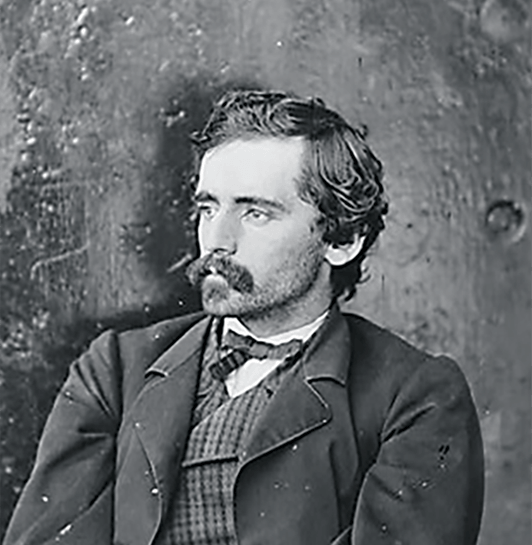

assassination, Booth’s brother Edwin, a staunch Unionist and Lincoln supporter, admitted he was no closer to understanding his infamous younger brother.

“He was so peculiar. I never seemed to know him,” he said.

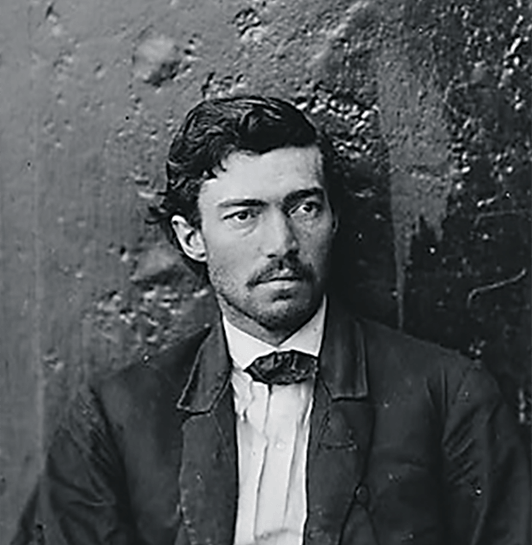

Gold-toned daguerreotype of Junius Brutus Booth taken between 1844-1852.

John Wilkes Booth made his debut on May 10, 1838, in Bel Air, Maryland, the ninth of 10 children born to Junius Brutus Booth and Mary Ann Holmes. His parents were English but emigrated to America in 1821, in part to further Junius’s acting career. It worked, and Junius quickly became the nation’s theatrical colossus.

He also built a reputation for being unconventional, temperamental, often drunk, and, sometimes, downright crazy. Tales of his exploits were legendary. As historian Terry Alford writes in the new biography Fortune’s Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth, “By the time John was born, Junius had compiled an unenviable résumé of trouble. He had shot one man in the face, assaulted others, attempted suicide on three occasions, and been jailed in four states. With the deaths of [four of] the children in the mid-1830s, Junius grew even odder and the number of disturbances increased. In 1835, he wrote to Andrew Jackson threatening to cut the president’s throat.”

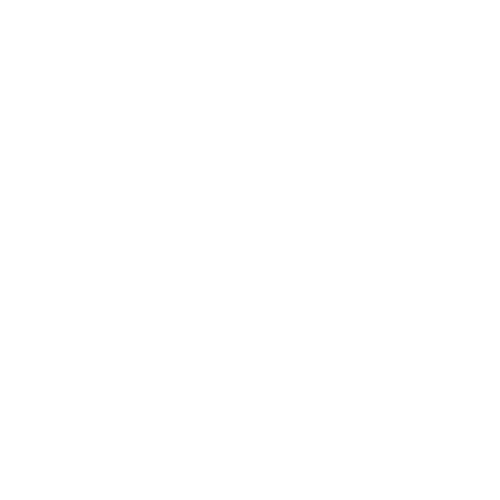

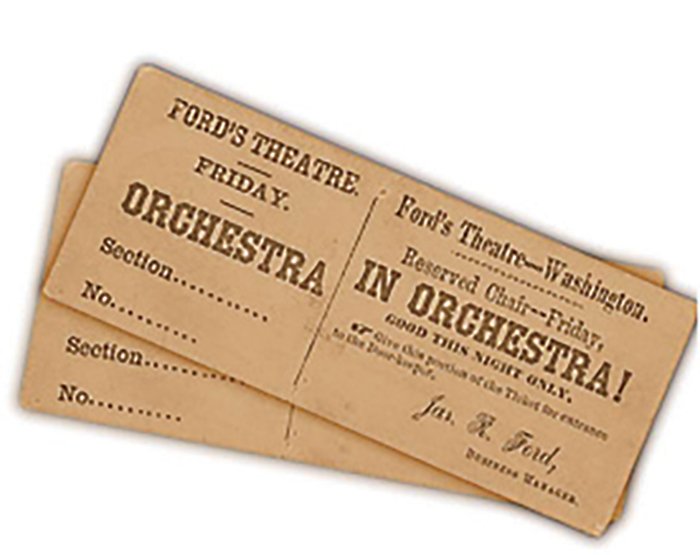

From top to bottom: Booth, left, with brothers Edwin, Center, and June in Julius Caesar, Nov. 1864; Playbill and tickets for Our American Cousin; one of the last photos of Abraham Lincoln, taken Feb. 5, 1865.

Perhaps the biggest scandal to embroil Junius—and that’s saying something—erupted in 1846, when it was revealed that, the entire time he’d been in America, he’d had a second family back in England, with neither family aware of the other. The papers had a field day after his English wife came to Baltimore to confront him. Eventually, he obtained a divorce and officially married Mary Ann on John Wilkes’s 13th birthday.

But Junius had many redeeming qualities too. He could be gentle, generous, and captivating, and he was nowhere more likely to display these characteristics than at the family farm in Bel Air.

Living at the farm with the Booths were Joseph and Ann Hall, two African-American workers. Junius detested slavery. There is evidence that Junius and his father, Richard, occasionally sheltered runaway slaves on the Bel Air property. In accordance with these beliefs, the Halls were paid and treated like family. Ann Hall helped raise the children and loved John like a son. In fact, not even his murder of Lincoln, the great emancipator, could shake her loyalty. Asked by a neighbor afterward if she would help John should he turn to her, she replied, “Indeed, I would, honey. Give him all that I have.”

That the elder Booth’s abolitionist leanings were absorbed by some of the children and not others was not uncommon. The ideological differences that resulted in the Civil War were also played out within families. Tom Fink, president of the Junius B. Booth Society, a nonprofit that is working with Harford County to turn the old Booth homestead into a museum, thinks John would have turned out very differently had Junius been around more. “Junius died in 1852 when John was just 14 years old,” he explains. “Previous to that, Junius was on the road most of the time, so John didn’t really have that father figure helping him along and teaching him his values.”

In many ways, Booth’s mother, Mary Ann, was a single parent, and she and John were especially close. Family lore has it that while nursing him by the fire one night, Mary Ann had a vision and saw the word “country” spelled out in the flames. She interpreted this to mean he would die for his country, a belief that made her especially protective. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, she made Booth promise he wouldn’t fight, a pledge he kept, until he could no longer stand it.

Stories, especially Greek histories and Shakespeare, were the lifeblood of the Booth family, and John was particularly enamored. He was attracted to the dramatic, the romantic, the larger-than-life. If he could combine these tales of glory with reckless action, all the better. According to Alford, he would ride through the woods on his horse “shouting heroic speeches, and waving an old lance.” But mostly, Booth’s was a garden-variety country boyhood: lighting firecrackers, searching for Native American remains in the woods, and roughhousing with other boys. The only notable thing about his behavior to his sister Asia was that, “He is [always] the one to be hurt or found out, and all the rest get off clear. And he’s not a bit worse than they.”

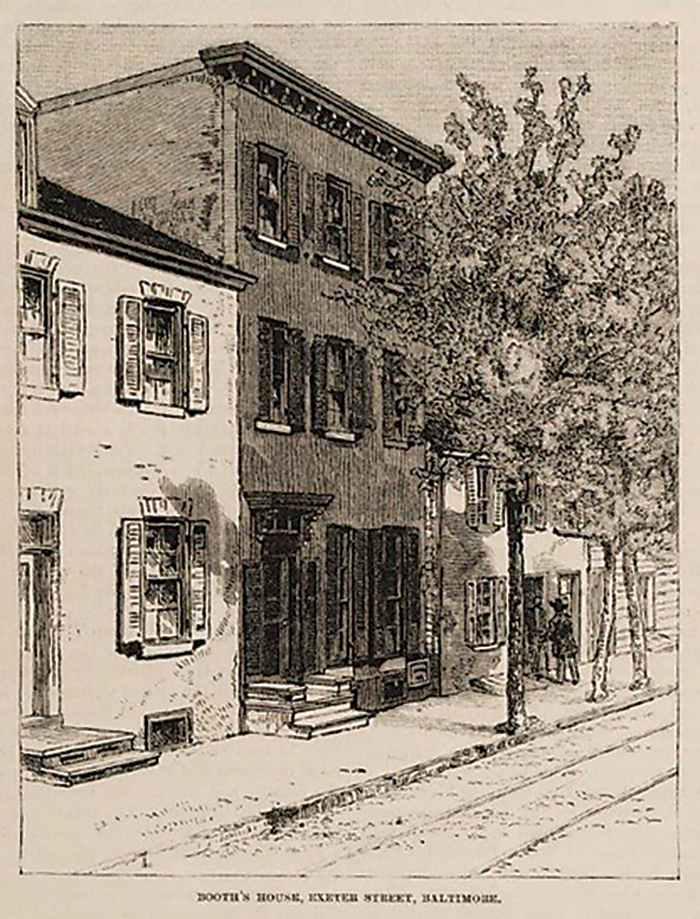

In 1845, Junius moved the family from Bel Air to Baltimore’s Old Town neighborhood, just above where Little Italy is today. From then until Junius’s death in 1852, the family would split its time between the brick townhouse at 62 North Exeter Street and the farm in Bel Air where Junius had decided to supplant the existing whitewashed log house with a grand Gothic-style cottage that Asia dubbed Tudor Hall. Because Tudor Hall still exists and the Baltimore townhouse is long gone, the perception persists that the Booths were primarily a Bel Air family, but Baltimore shaped them as much as Bel Air.

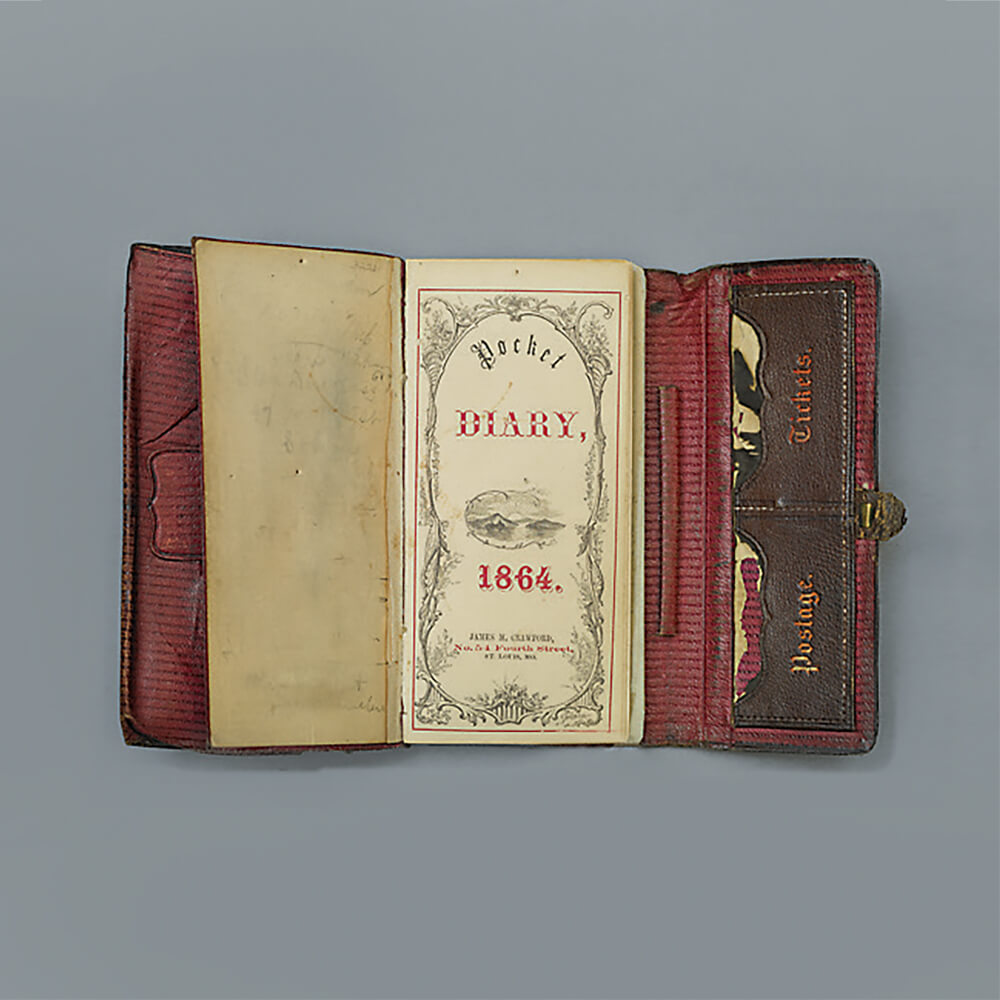

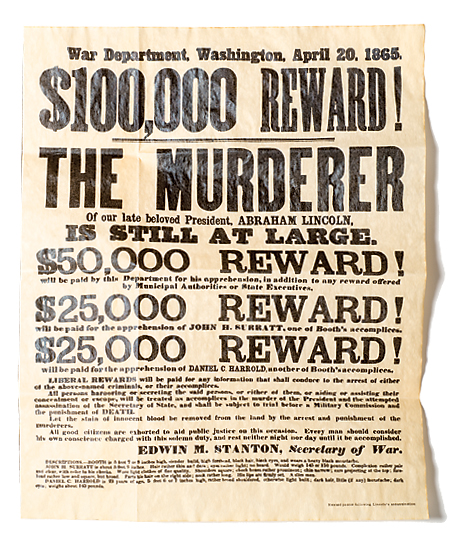

PERSONAL EFFECTS: ARTIFACTS FROM FORD’S THEATRE COLLECTION

From left to right: The single-shot, .44-caliber deringer pistol Booth used to kill President Lincoln; Booth’s pocket diary in which he recorded his thoughts while on the run after the assassination; Booth’s boot, which Dr. Samuel Mudd cut off of him in order to treat his injured leg; horn-handled dagger (with sheath) used by Booth during the assassination.

Baltimore in the 1840s was the second-largest city in the country and an eager participant in the burgeoning Industrial Revolution. “As a result,” Alford writes, “John’s childhood was more cosmopolitan than that of most others who found their way to the Confederate cause. While their roots tended to be exclusively rural, his mixed the country with the most sophisticated city life the South offered.”

Booth’s schooling was a mixed bag as well. He started in a one-room schoolhouse across the road from the farm before moving on to the more prestigious Bel Air Academy and then to the Milton Academy for Boys in Sparks, a Quaker boarding school housed in the fieldstone building that is now The Milton Inn. An undistinguished student who had difficulty learning through traditional methods, Booth’s school days were most notable for what occurred outside of the classroom. While at the Milton Academy, Booth gave what was likely his first public performance, as Shylock in a scene from The Merchant of Venice.

From top to bottom: Etching of Booth home at 62 North Exeter Street; The Milton Inn (formerly Milton Academy); mural depicting Edwin Booth At the Bel Air Post Office; reproduction of wanted poster for Booth and conspirators.

During this time, he also met a gypsy who told his fortune, which he later breezily relayed to Asia. “Ah, you’ve a bad hand; the lines all cris-cras [sic],” the gypsy is to have said. “Full of trouble. . . . You’ll die young, and leave many to mourn you, many to love you, too, but you’ll be rich, generous, and free with your money. You’re born under an unlucky star. . . . You’ll make a bad end.” Whether it was an intuition, a premonition, or just a lucky guess, the gypsy’s words added to Booth’s growing sense of himself as a doomed romantic hero.

Booth’s final school was St. Timothy’s Hall in Catonsville, an Episcopalian military academy that attracted students from some of the South’s best families. Accustomed to far more latitude than the school’s strict code of behavior allowed (no drinking, no smoking, no playing cards, no coarse language, no firearms, no food from home, etc.), Booth chaffed at the strictures and continued to struggle academically. But he also began to adapt and find his own identity separate from his family’s long shadow.

School ended for Booth at the age of 15 following his father’s sudden death. Without a steady income to support the family, his mother rented out the Baltimore townhouse and proposed farming at Tudor Hall. With the older sons, June and Edwin, already off pursuing their own acting careers, John suddenly found himself the head of the household and a farmer to boot.

In her memoir, Asia remembers the era fondly, as years of happy, simple domesticity, when John rose with the sun in his east-facing bedroom, worked the fields, and then attended country dances at night. But the truth was, he was a lousy farmer, dead tired, and yearning for the stage. When Edwin returned from the West in 1856 and suggested the family rent out the farm and return to the city, John was relieved.

Free to pursue his own goals, Booth aimed for the stage. He was determined to equal if not eclipse the success of his father.

Booth had made his first appearance on the professional stage on August 14, 1855 in Baltimore in a one-off performance as Richmond in Richard III. After he was able to cast off the yoke of farming, a friend procured him an entry-level position in the stock company at Philadelphia’s Arch Street Theatre. He would be billed as “J. B. Wilkes.”

Though his early performances were shaky at best—Booth was visibly nervous and, on one occasion, forgot his character’s name—most agreed he had potential. His greatest strength was his exciting and visceral stage presence. He excelled in fight scenes, but also performed ably in romances, comedies, and tragedies. And it escaped no one’s notice that he looked, in the words of one acquaintance, like a “young Apollo.”

Booth was asked back for the following season in Philadelphia, but declined, feeling he’d failed there. He moved on to the Marshall Theatre in Richmond, VA, which was co-managed by Baltimore theater manager and family friend John T. Ford. He loved Richmond, and Richmond loved him back. There he ascended to star status and began using his own name on playbills.

It was also while there that national politics began to intrude. The nation was staggering ever closer to a crisis regarding slavery. Skirmishes out in the western territories between pro-slavery and abolitionist militias were increasingly common. Still, it seemed to most Virginians like a problem that was far away. But the problem came to their doorstep when radical abolitionist John Brown mounted an attack on the federal arsenal in Harpers Ferry in October of 1859. His goal was to incite a slave uprising using weapons from the arsenal. For many Southerners, this was their worst nightmare. Booth was horrified. According to Alford’s biography, Booth told friends he wanted to “help shoot the damned abolitionists” himself.

After Brown was captured and sentenced to death, militias were called up to maintain security before and during the hanging. Richmond units went, and though Booth was not a member, he went with them. The experience was profound. The day before the execution, Booth visited Brown in jail. (Unfortunately, their conversation is lost to history.) The next day, Booth stood about 30 feet away from the scaffold as Brown was hanged. He came away from the experience with no new sympathy for the abolitionist cause but much respect for Brown, even keeping a piece of Brown’s coffin and a spear Brown had used in the raid as souvenirs, two talismans unwittingly passed between opposing zealots. “He was a brave old man; his heart must have broken when he felt himself deserted,” Booth later told Asia.

Back in Richmond, Booth picked up where he left off, packing in audiences and romancing as many women as he could juggle. In the fall of 1860, he embarked on his first starring tour, stopping in small cities in Georgia and Alabama. The tour hit a snag however, when Booth’s manager accidentally shot him in the leg forcing him to miss several performances while he convalesced.

He rebounded in early 1861 with a tour of several smaller Northern cities, playing Albany, NY, on the night Lincoln passed through en route to Washington for his inauguration. But just as Booth was gaining professional momentum, the war broke out.

PARTNERS IN CRIME

There were nine notable conspirators involved in the Lincoln assassination plot. Most were captured quickly. Four were put to death; four were imprisoned; and one was tried but not convicted.

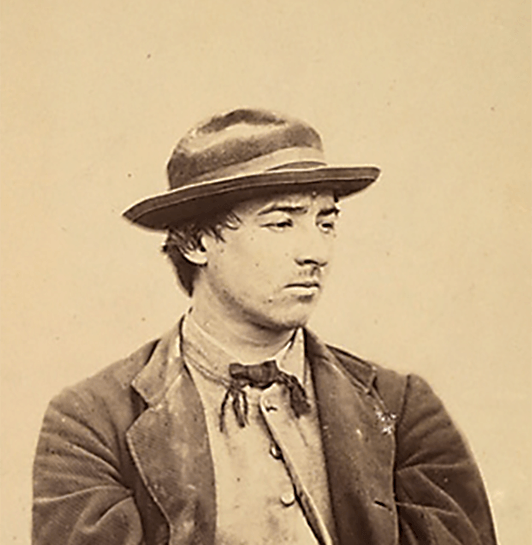

David Herold Former druggist’s assistant. Accompanied Booth on attempted escape. Hanged, July 1865.

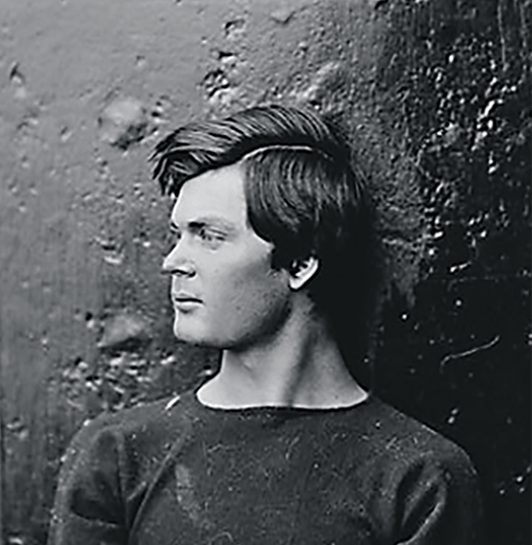

Lewis Powell Confederate veteran and attacker of Secretary of State Seward. Hanged, July 1865.

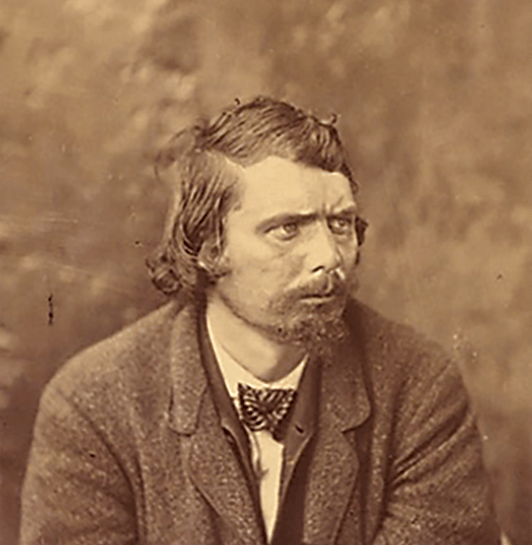

George AtzerodtGerman-born Marylander told to kill Vice President Johnson, but didn’t. Hanged, July 1865.

Mary SurrattWashington, D.C. boarding house owner and mother of John Surratt. Hosted conspirators. Hanged, July 1865.

John Surratt Son of Mary Surratt. Evaded arrest for over a year. Eventually tried but let off by a hung jury.

Samuel ArnoldSchoolmate of Booth’s at St. Timothy’s. Sentenced to life in prison. Pardoned in 1869.

Michael O’LaughlenChildhood friend of Booth’s. Sentenced to life in prison. Died in Florida jail in 1867.

Edman SpanglerStagehand at Ford’s Theatre. Asked to hold Booth’s horse during assassination. Given six-year sentence. Pardoned in 1869.

Dr. Samuel MuddDoctor who set Booth’s leg. Sentenced to life in prison. Pardoned in 1869.

Though it’s uncomfortable to acknowledge, war can be good for some people. Ulysses S. Grant was an aimless drunk before the Civil War made him a military hero. After the war, he became a two-term president. The war was good for Abraham Lincoln, too. Over the course of the war, he went from personally believing the right thing to actually doing the right thing, and he dragged the country along with him—knocking the laws of the land into better alignment with our highest ideals.

The Civil War was not good to John Wilkes Booth. It undid him. Sure, he was thriving professionally. He toured Chicago, New York, Boston, St. Louis, and Baltimore. He performed in Washington at least once with the President in the audience and, on a separate occasion, with the President’s son, Tad, in attendance. And his reviews were the best of his career, referencing his “originality” and “genius.” Emotionally, however, Booth was unraveling. The country was changing and he couldn’t—or wouldn’t—change with it. As Alford writes, “His powerful personality harbored consuming likes and dislikes. . . . It was impossible to change his mind. . . . Booth never had a new thought after his core opinions were formed in his teenage years.”

As a Marylander, Booth found plenty to dislike during the war. Then, as now, debate raged about Maryland’s identity as a Southern or Northern state. Slavery was legal in Maryland, so the state could have sided with the Confederacy. If it did, Washington, D.C., would have been surrounded by hostile territory. Lincoln couldn’t risk Maryland’s secession. So in May 1861, Lincoln sent 1,000 federal troops into Baltimore to occupy the city, aiming cannons at the downtown from atop Federal Hill. Martial law was imposed and the mayor, police marshal, and board of police commissioners—among others—were rounded up and imprisoned at Fort McHenry without charges or trial. The men complained that their detention was in violation of the rule of habeas corpus and some members of the Supreme Court agreed. Lincoln ignored them. In fact, in September of 1861, federal troops and Baltimore police officers arrested all pro-Confederate members of the Maryland General Assembly during a special session in Frederick.

A gothic-revival "cottage," Tudor hall replaced the family's whitewashed log cabin and was to be Junius's dream home, though he died before it was finished.

Like most Baltimoreans and Marylanders, Booth resented these infringements. Through his family, he knew some of the incarcerated, and he began to think of Lincoln as a tyrant grinding Maryland—and indeed the nation—under his boot heel. What he wanted was to fight for his country, by which he meant the South. But his promise to his mother kept him in check.

Sometime in 1864, he vented his feelings in a letter to her. “For four years I have lived (I may say) a slave in the north (a favored slave it’s true, but no less hateful to me on that account). Not daring to express my thoughts, even in my own home. Constantly hearing every principle dear to my heart denounced as treasonable. And knowing the vile and savage acts committed on my countrymen, their wives, and helpless children, I have cursed my willful idleness. And begun to deem myself a coward and to despise my own existence. For four years, I have borne it mostly for your dear sake. And for you alone have I also struggled to fight off this desire to be gone.”

As his radicalism waxed, his interest in acting waned. He suffered vocal problems and tired of the road. He did appear in the occasional benefit performance, the most famous—and ironic—being a performance of Julius Caesar with his brothers in November 1864. But mostly his attention was elsewhere. He speculated in oil in Pennsylvania and visited family and friends—and there were always women. Above all, he plotted.

It is unclear exactly when Booth began to consider a plot to kidnap Lincoln and hold him for ransom in exchange for Confederate prisoners of war, but by August 1864, he had set the wheels in motion. He recruited fellow Southern sympathizers to his cause, starting with his old St. Timothy’s schoolmate Samuel Arnold and his childhood friend from the Old Town neighborhood, Michael O’Laughlen. Eventually the group grew to include David Herold, George Atzerodt, Lewis Powell, John Surratt, and his mother Mary Surratt, at whose boarding house the conspirators often met, see below.

If assassination had been the goal at this point, Booth would have had a perfect opportunity on March 4, when he attended Lincoln’s second inaugural as the guest of Lucy Hale, the daughter of a New Hampshire senator and vocal abolitionist. A picture exists of that day, and sure enough, above Lincoln, in a scrum of guests on a raised platform, Booth is visible.

The closest the conspirators got to enacting their plan was on March 17 when the President was scheduled to attend a play at a hospital. The conspirators prepped, but Lincoln’s plans changed, and an attempt was never made.

After this, the enthusiasm of several of the conspirators began to flag, but Booth held steady, insisting they try again. The events of April 9 changed all that. That day, General Robert E. Lee surrendered his Army of Northern Virginia to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, VA. Other ragtag bands of Confederate soldiers would fight on for a few weeks, but symbolically, the war was over. The South had lost. Booth knew that a kidnapping was too little, too late.

On the evening of April 11, 1865, a jubilant crowd gathered in front of the White House to hear Lincoln give what would be his final public address. In it, he touched on his plan for Reconstruction and called for black suffrage. Standing in the crowd next to co-conspirator David Herold, Booth seethed, “That means nigger citizenship. Now, by God, I’ll put him through.”

At tudor hall, John Wilkes Booth used the balcony outside his room to practice dramatic scenes and speeches.

He got his chance just three days later, when, picking up his mail at Ford’s Theatre, he learned that the President would be attending that evening’s performance. He improvised a new plan in which he would kill the President while co-conspirators David Herold and Lewis Powell would kill Secretary of State William Seward, and George Atzerodt would kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. Booth’s hope was that, in doing this, they would plunge the federal government into chaos, thus giving the Confederacy a reprieve.

Atzerodt, though, got cold feet, and Johnson was never attacked. Herold helped with reconnaissance, but did not participate in the violence. Powell, however, brutally stabbed Seward several times in the face and neck. Miraculously, Seward survived.

After Booth shot him, Lincoln never regained consciousness. He was carried from the theater across the street to a house where he died the next morning. “We shall appreciate him at last,” predicted New York lawyer and diarist George Templeton Strong when he heard the news. How right he was. Never popular until he died, Lincoln was almost immediately elevated to the status of secular saint.

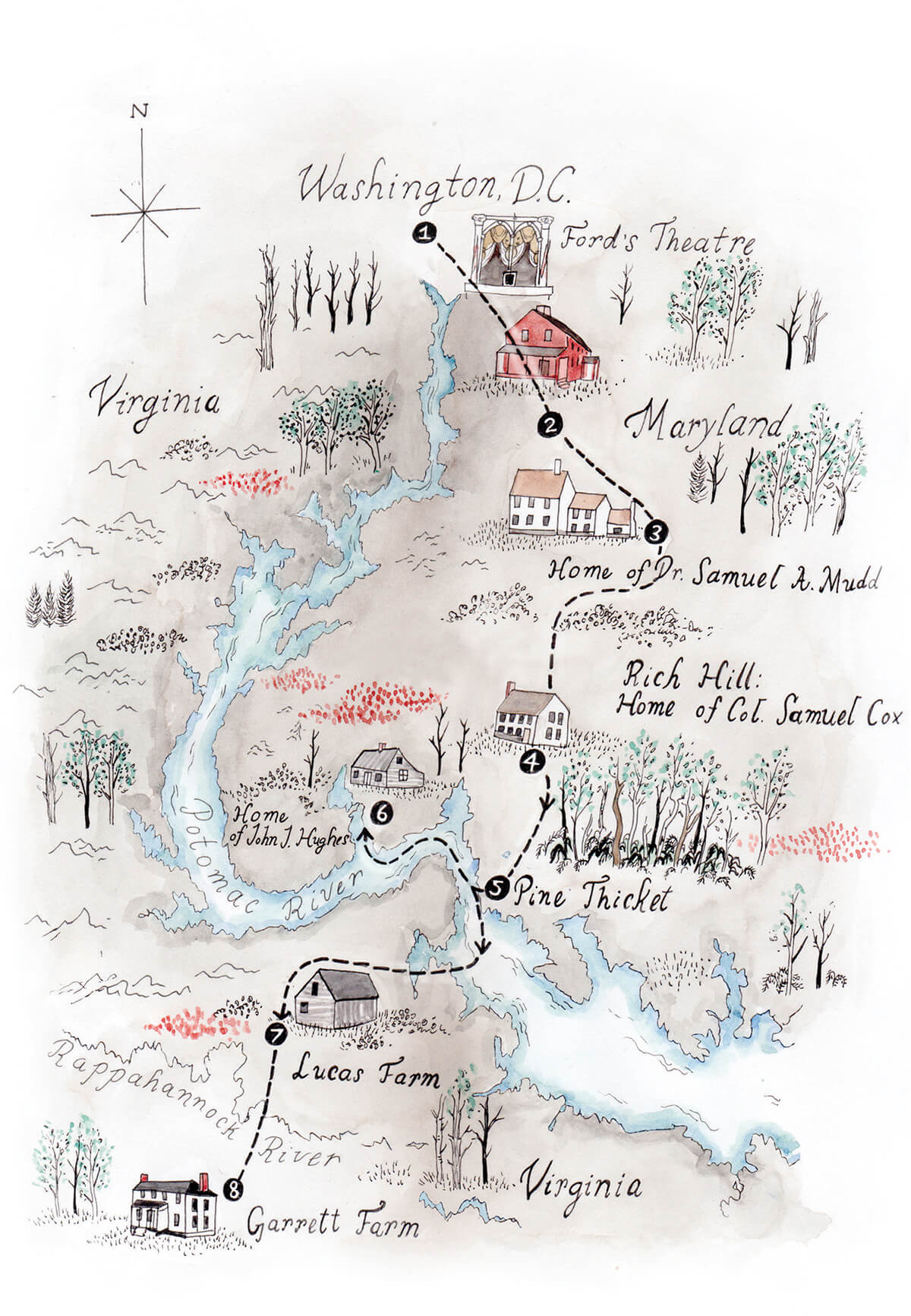

As the nation began an extended period of mourning, Booth, accompanied by Herold, was making his way through southern Maryland, hoping to cross the Potomac into Virginia where he might find safe harbor, see map, page 160. Writing in a pocket diary, Booth recorded his dismay at the public reaction to the assassination. “I am here in despair. And why: For doing what Brutus was honored for, what made [William] Tell a hero. And yet I, for striking down a greater tyrant than they ever knew, am looked upon as a common cutthroat,” he pouted.

Booth and Herold made it to Virginia but found little welcome. Even those inclined to approve of Booth’s crime were reluctant to help in case they became targets of the massive manhunt underway. Finally, on the morning of April 26, Union troops surrounded the barn in which Booth and Herold were hiding. Herold quickly surrendered, but Booth, proud to the end, refused. Hoping to force him out, the troops lit the barn on fire. As it burned, a soldier man named Boston Corbett fired at Booth. The shot hit him in the back of the neck, piercing his spinal cord. Booth was then pulled from conflagration and carried to the porch of the nearby farmhouse where—fully conscious but paralyzed—he waited to die. As death approached, Booth said, “Tell my mother I die for my country.” Then, he looked at his limp hands and uttered, “Useless, useless.”

THE ESCAPE ROUTE

While Lincoln’s legacy is clear-cut and assured, Booth’s is thorny. He is undoubtedly an important and fascinating historical figure, but there is a question of how much attention and remembrance he deserves—especially when he remains a folk hero to some anti-government radicals. (For instance, when Timothy McVeigh carried out the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, he wore a T-shirt emblazoned with Booth’s favorite motto: sic semper tyrannis.)

Tom Fink of the Booth Society knows that most of the visitors to Tudor Hall come because of John Wilkes. Some are Civil War buffs, some are conspiracy theorists who think Booth got away, some are modern-day Confederates, and some, mainly women, are nursing major historical crushes on the dashing assassin. “They come in all starry-eyed. They say, ‘Tell me about John! I have such a crush on him,’” he says with a bewildered chuckle. But Fink hopes that, once inside, visitors come to appreciate the rest of the clan, too. “Junius [Sr.] and Edwin are my two favorites,” he says. “I love what they did for theater and just their fascinating, complex lives.”

The Booths themselves understood that John’s actions cast a long shadow over the family. After the assassination, they all—to varying degrees—spent the rest of their lives walking a tightrope between shame and stubborn, familial attachment.

For four years after his death, Booth’s remains were stored in various government facilities until, after several requests, they were released to the family for burial. The family brought him back to Baltimore for interment, and he still reposes in the family plot in Green Mount Cemetery. Edwin decided his brother's grave should bear no permanent marker lest it become a shrine. But that doesn’t stop hundreds of people from making the pilgrimage to the cemetery every year. Though Green Mount is the final resting place of several notable names including Johns Hopkins, Enoch Pratt, and a handful of Civil War generals, the biggest draw—by far—is John Wilkes Booth. “Oh yeah, we know who people are going to look for when they come in,” says one administrative assistant. “Poor Johns Hopkins,” she continues shaking her head, “No one ever comes looking for him.”

Many visitors think that a small stump of marble in the far left corner of the family plot indicates Booth’s location, but it doesn’t. It’s actually his sister Asia’s footstone. Still, many leave pennies, bearing the profile of the slain President, on top of it to condemn Booth. But some visitors leave other tokens, too.

On a clear day in January, a bouquet of faded red roses lies on the obelisk that anchors the family plot. Elsewhere in the cemetery, a single rose decorates the headstone of fellow Lincoln conspirator Samuel Arnold. (Curiously, conspirator Michael O’Laughlen’s grave, also located in Green Mount, is flowerless.) That Arnold’s grave earns a rose too makes it likely that the bouquet is intended for John Wilkes and not any of his kin. Asked why someone would leave flowers for a dead presidential assassin, the office assistant just gives a wry smile and a seen-it-all shrug and says, “I guess ’cause he’s a bad guy.”