News & Community

Boom Town

Will Towson shake its identity crisis and become the next Bethesda?

Brian Recher looks like a proud father on a recent afternoon as he leads Towson Chamber of Commerce executive director Nancy Hafford on a tour through his and his brother Scott’s burgeoning mini-business district on York Road. The tour starts at their expanding, upscale Towson Tavern restaurant, which takes its name from Ezekiel Towson’s 18th-century tavern that was one of the first commercial establishments here.

“We’re adding 30 to 40 outdoor dining seats over the next six months,” Recher says, almost surprised himself.

Next, they head two doors down to the brand new Torrent nightclub that the brothers have launched inside the former Recher Theatre—the live music venue they operated for 17 years. Recher enthusiastically describes the club’s state-of-the art sound system and, for a moment, gets nostalgic recalling that decades before the brothers turned the space into a live-music venue, the site had been home to their parents’ single-screen movie house.

“I tore tickets and sold popcorn,” Recher says. “My first job.” He also fondly recalls some of the great bands that played the Recher Theatre over its run, from Baltimore County’s own Animal Collective to Iggy Pop, Patti Smith, and The White Stripes.

But he remembers, too, his parents’ struggle, over time, to keep their movie theater open, as well as the eventual closing of even the AMC cinemas across the street that had earlier put his parents out of business. He knows his own struggle to keep the Recher viable as a music venue—“we considered shutting it down for three years before making the decision last year”—as well as the numerous Towson Commons restaurants and businesses that were shuttered over the past two decades.

Yet, despite that history, the Rechers have doubled down on their Towson investments, and the reason—or one big chunk of it at least is currently dusting up the air and patio tables behind the Rec Room, the successful bar they run between Torrent and the Towson Tavern.

Wiping his hand across the outside bar, Recher holds up a few dirt-covered fingers for Hafford’s inspection. “We just cleaned this last night,” he says with a knowing smile. He’s grinning because, since sunrise, backhoes have been putting the finishing landscaping touches on Towson Square—an $85 million, 15-screen Cinemark Theatre entertainment and restaurant complex—due for a ribbon-cutting around July 4.

“There’ll be 3,400 seats there,” Recher says. “A multiplex like that can pull 15,000 to 20,000 people on a weekend.”

But here’s the big picture: That’s not even the largest project in a suddenly bursting Towson redevelopment pipeline. That honor goes to the planned $300-million Towson Row project, an office, condo, hotel, restaurant, and retail development just a couple of short blocks south on York Road that promises to dramatically reshape Towson’s skyline. In fact, there are more than a half-dozen other major new projects either recently completed or in various stages of development, including the $27-million renovation of the once vacant 12-story City Center Building, already open and thriving just above the Towson Circle—home to Cunningham’s, a brand new foodie-favorite Bagby Group restaurant, and the new WTMD studios.

There’s also the planned $60-million 101 York student-housing-and-retail project closer to Towson University, plus an array of new residential projects—the Towson Green townhomes, The Winthrop luxury apartments, The Quarters at Towson Town Center apartments, and The Palisades, an amenities-loaded downtown high-rise, which opened in 2011. Altogether, the total is more than $770 million in recent private investments in the once sleepy county seat. And, there’s still more: another $11.5 million in public investments and, indirectly related, a planned $1.1 billion in capital projects from Towson University as the school’s population swells over the next decade. The question is no longer if downtown Towson is finally taking off, but will it join Bethesda and Harbor East as the region’s next urban-renewal success story—a livable, working, shopping, lifestyle destination of choice. You can’t quite blame people for being skeptical.

With 55,000 residents and an even larger number of jobs, Towson has long seemed poised for a great leap forward. It possesses the kind of intrinsic characteristics that urban-design wonks and developers love, i.e. a downtown street grid, which promotes density and storefront businesses, pedestrian-friendly sidewalks—which are being upgraded in the York Road corridor—attractive demographics, proximity to a major city, good public schools, and a stable job market. It’s the center of county government and host to other large employers like the Sheppard Pratt Health System, St. Joseph Medical Center, and the Greater Baltimore Medical Center. Of course, it’s bookended by Towson University and Goucher College, which also translates into recession-proof jobs.

And yet, there have been previous attempts to give Towson a downtown identity that have failed. The aforementioned AMC at Towson Commons opened amid great expectations in 1992 and then closed in 2011 after many years of dwindling attendance. An eight-screen movie theater in the heart of a college town seemed liked it couldn’t lose, but as larger multiplexes were built around town—with their stadium seating and IMAX screens—Towson got left behind. And as attendance fell, other businesses in Towson Commons were dragged under, too. Restaurants like Paolo’s and Ruby Tuesday, as well as Borders Books & Music, closed several years before the theater went dark for good.

“It’s a sad ending,” County Councilman David Marks, who represents Towson, told The Baltimore Sun just three years ago. “I remember going there in the early 1990s. It was the cornerstone of Towson.”

But county officials and developers say this time is different for a variety of reasons—a significant jump in the county’s population in the past three years; big local developers, such as Caves Valley Partners, the Cordish Companies, and the Bozzuto Group stepping up to the plate; and simply, long-standing parcels of land becoming available for sale and consolidation—which have all begun to build on each other.

“What has been happening, as far as the new projects, is on a lot of land in Towson that been held by older families for a long time,” says Baltimore County director of planning Andrea Van Arsdale “And then there was a switch, if you will, to control of the land to younger members of the family, who were more willing to take a risk and work with brokers and developers. The 101 York is an assemblage of a lot of small parcels. The Bozzuto property [the Towson Green townhomes] was 30-some parcels with 11 different owners. The Palisades was an assemblage of six or seven lots over time.”

Michael Batza of Heritage Properties, which is partnering with the Cordish Companies on the Towson Square project, has lived in Towson for more than 30 years, and says the balance of the properties on that development were acquired and assembled years ago over a three to four-year period in the aftermath of the closing of the old Hutzler’s department store (now home to Barnes & Noble, among others). “The project has evolved from student housing to office and retail,” Batza says. “The Cinemark Theatre-lifestyle-entertainment complex now has been six years in the making. It hasn’t been an easy project.”

Recher, for his part, marvels at the massive influx of development.

“I grew up here and love it—I got my first haircut at the strip mall where Towson Town Center now stands—but who would’ve thought?” he says shaking his head. “Small, little Towson.”

Van Arsdale explains it this way. “In the past, there’s been a lot of fits and starts, followed by long periods of quiet,” adding only half-jokingly that she’s spent 15 years, much of her career, working on Towson’s revitalization. “This is Towson’s ‘Big Bang,’” she says. “It’s a confluence of things that have brought about what is happening now—some taking a long time to come together.”

Of course, one of the keys is getting people to think about Towson in a new way. But that has already started, too.

As the colleges have grown, they have brought more significant cultural cache to town, in terms of concerts, theater, lecture series, films, and sporting events—no small thing when trying to capture the young professional residential market today. “We’re becoming more urban and more urbane,” Van Arsdale says. The Towson University-affiliated WTMD already hosts “Live Lunch” concerts in its new space each Friday and, says general manager Steve Yasko, hopes to develop into a bit of a destination itself, similar to Philadelphia’s WXPN, the University of Pennsylvania-affiliated public station, and it’s acclaimed World Cafe programming. Yasko also notes that WTMD was scheduled to host the 2014 Baker Artist Awards at its studios in mid-May and envisions hosting similar events in the future.

“We see this as a gallery space, too,” Yasko says. “We can fit 50 people here for something intimate or open it for 200, if necessary.”

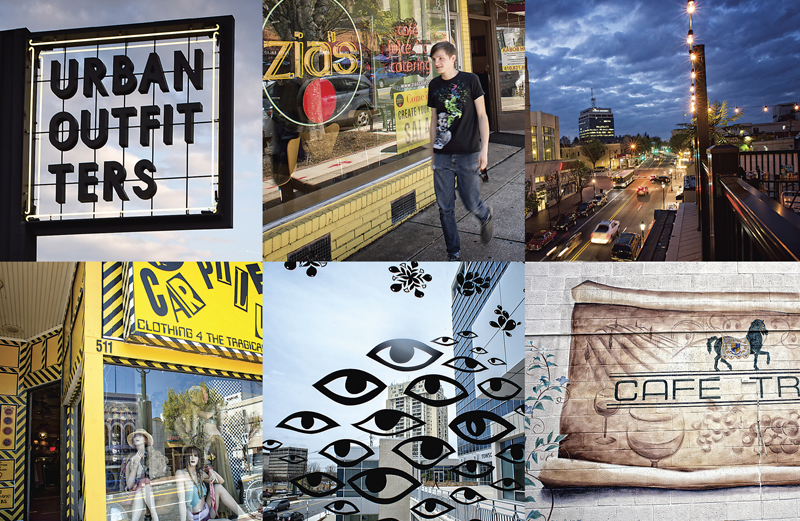

Even before the arrival of Cunningham’s, Towson was already becoming something of a foodie-haven, known for the stalwart, fine-dining of Café Troia, as well as smaller ethnic restaurants, including numerous sushi venues, the Vietnamese Pho Dat Thanh, and Havana Road Cuban Café. Along with WTMD, the Urban Outfitters that opened two-and-a-half years ago, and La Cakerie, the nearby bakery founded by Jason Hisley of Cupcake Wars fame, have added hipster appeal. “For us, downtown Towson really has all the demographics we’re looking for,” says Hisley. “Like Bethesda, there’s the higher-end, that’s part of it, for our catering. But there’s also a lunch business, which we do, the residential side, which is a lot of our cupcake and party-cakes business, and the students—the college munchies crowd. The new movie theater, Towson Square, is going to bring more people downtown, too, and we’re going to do some live music soon, make it more of a hangout with a European coffeehouse feel,” continues Hisley, adding he plans to expand the store’s hours later into the evening.

“Towson has always ranked very high in demographics—its income and education levels—it just did not have a great, corresponding ‘quality of life,’” says Baltimore County Executive Kevin Kamenetz. “It’s been a place where the sidewalks closed at 5 p.m. We want to build up the residential side and the nightlife, increase the foot traffic, and keep it open longer.”

More and more, that seems like a viable option—not that there aren’t potential pitfalls. Compared to other thriving “suburban” cities, such as Bethesda, Silver Spring, Arlington, VA, Clarendon, VA—or farther afield, Cambridge, MA—Towson’s most obvious “minus” is a lack of a metro line or light rail stop at a time when more people, especially millennials and younger families, are moving away from a car-centric lifestyle.

For many years, streetcars connected Towson and other inner-ring suburbs to Baltimore, and the lack of a light rail makes it a less-inviting destination for people who work or live in Baltimore City or Hunt Valley, for example. There are weekday buses that run between Penn Station and downtown Towson, but traffic congestion and parking remain challenges—and issues that have been raised repeatedly by current residents at numerous local meetings.

“There’s been a cultural shift taking place,” notes Baltimore County Councilman David Marks, a former Maryland Department of Transportation (MDOT) chief of staff, who represents Towson. “Even Columbia, once modeled as the suburban utopian, is now trying to address it by creating density and a downtown urban core. But that’s not on a metro stop, either.”

The Towson Row project, in particular, has refueled discussions with MTA about creating a Charm City Circulator-type free bus system in Towson, but nothing is in the works so far. The Towson Bike Beltway—a striped bike-lane route pushed by Marks, linking the colleges, the Towson Town Center, Towson Place, and downtown Towson—is moving forward and should at least encourage more bicycle commuting for short trips. “We really have to have a transit circulator by the time the Towson Row project is completed in 2018,” says Marks, who expects as many 3,000 to 5,000 new residents eventually in greater Towson. “That’s going to be like what Manhattan is to New York City,” adding there are no building-height restrictions in downtown Towson.

On his own tour of the overhauled former AMC movie theater in the Towson Commons building—including a new, $7 million-plus, 52,000-square-foot LA Fitness—Kamenetz acknowledges backlash from some long-standing residents because of congestion fears. (Not completely unwarranted, either. The gym alone—the facility features an indoor pool and basketball and squash courts—can draw upwards of 1,500 people a day to downtown Towson.)

“It’s change, and change isn’t easy,” says Kamenetz, who has maintained a focus on Towson’s development since being elected in 2010, according to several developers. “I understand that. What I would tell those people is that we can’t keep your property taxes where they are if we don’t attract new investment; we can’t build new schools or repair our roads; maintain our AAA bond rating.”

Security concerns have also been raised, Kamentez acknowledges, particularly in light of a recent uptick in 2013 Towson precinct robberies and assaults, and given the size and nature of the Towson Square project. But he says the county is adding five uniformed police officers and will be placing Segway patrols in the Cinemark complex area and elsewhere.

Additionally, says Kamentez, with 18,000 new county residents in just the last three years, what’s good for the county’s urban cores is also good for rural Baltimore County. Placing new residents and businesses in urban areas, he says, is essential to maintaining the northern horse-farm country, and places like Gunpowder Falls State Park, and the Pretty Boy Reservoir and Loch Raven Reservoir watersheds.

In fact, he continues, placing development in already developed areas is required by Baltimore County’s master plan and historic urban-rural demarcation line—the groundbreaking “smart growth” zoning legislation established in 1967 that protects much of the county from development.

“Portland likes to say they were the first, but we were,” planning director Van Arsdale says with a laugh.

There’s another long-standing concern, especially for those familiar with patterns in urban development, namely the ever-expanding Towson Town Center—the type of giant indoor mall that’s always served as the death knell for a community hoping to enliven its downtown.

However, while it may have contributed to the I-83 suburban flight from Baltimore City when it was built in 1959—and also the stagnation of downtown Towson’s shopping district—it now has an opportunity to actually play a unique role in Towson’s revitalization. The numbers are almost hard to fathom, but it is an enormous magnet that draws 16 million shoppers into Towson each year. And, soon, if not this month, it will be within walking distance of the Towson Square movies and coming restaurants, which means a trip to the mall, dinner, and a movie no longer requires two or more car moves.

The buzz all the projects have been generating is interesting to look at, too. In 2012, CNN Money put Towson at No. 8 among the “best places for the rich and single.” Last year, the Nation’s Restaurant News included Towson as one of the “hot” nine markets for job growth in the U.S. Compare that to 2010, when a quieter, more low-key Towson was named the one of the “dream” places to retire by America Online.

“I was born and raised in Towson,” says Katie Chashey Pinheiro, executive director of the Greater Towson Committee, a nonprofit that promotes development and revitalization in the downtown area. “And I love Towson and that it’s always had this walkable downtown, which is only going to get better with the new streetscaping, once the scaffolding comes down, and the new projects that are going up.

“But I also feel like Towson never knew what it was—the home of county government, college town, residential community, small city,” continues the 34-year-old mother of two. “And now I think it’s going to being be all those things.”