News & Community

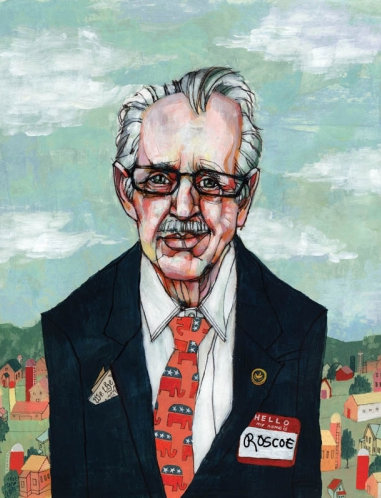

The Last Stand of Roscoe Bartlett

Maryland's Oldest & Oddest Congressman Fights For His Political Life

Congressman Roscoe Bartlett doesn’t have an entourage.

Congressman Roscoe Bartlett doesn’t have an entourage.

Almost every morning, around 6 a.m., the 20-year veteran of the House of Representatives, who will turn 86 in June, drives his Toyota Prius three miles from his Buckeystown, MD, farm to his office in Frederick. He shares the small building, which sits between a Chuck E. Cheese and a Wal-Mart, with a pediatric dentist’s practice.

Once there, he usually situates himself in a cramped conference room, reading a packet of clippings from various newspapers that have been compiled by his staff. He meets with constituents, has conference calls, and drives or carpools down to Washington, D.C., when Congress is in session, but always just for the day—he hasn’t spent the night there since he was first elected in 1992.

“The problem now is that your Congress is 90 percent run by professional staff,” says Bartlett, who wears an oversized navy-blue suit with a House of Representatives pin on his lapel. “Congress people have very little skill set. It’s run by faceless bureaucrats. I don’t need to rely on staff.”

In many ways, Bartlett, the second-oldest serving congressman after Texas’s Ralph Hall (who’s 89), is a throwback to an earlier era of citizen-politicians. He didn’t assume office until five years after he retired from a long and varied career that included stints as an engineer with the U.S. space program, the owner of a construction business, a professor at the University of Maryland and Howard University, and a farmer.

As a Representative, he’s let his conscience be his guide. He holds fast to constitutionalist principles of limited government—he keeps a copy of the Constitution in his breast pocket at all times, and quotes from it frequently—but he also has obsessed over issues far outside mainstream political thought, among them “peak oil,” the controversial idea that the global supply of oil is running out. (He founded Congress’s “Peak Oil Caucus,” which now has nine members, including six Democrats). He, along with Newt Gingrich, also frequently warns about the dangers of electro-magnetic pulse attacks on the U.S., which most experts consider far-fetched, and initiated Congressional hearings on the matter.

In general, Bartlett has not been afraid to buck his party’s line on a wide array of issues: He has consistently opposed the death penalty, the Patriot Act, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and describes himself as “far and away the greenest Republican in Congress,” boasting that he was the first person in Maryland—and the U.S. Congress—to buy a Prius.

“I was green before it was cool to be green,” he says. “My construction company was and is the largest home solar-equipment builder in Frederick County. I built 41 solar-powered homes.”

In 1992, Bartlett won his seat in the solidly Republican 6th district—which then included all of Western Maryland and the rural northern parts of Carroll, Baltimore, and Harford counties—by an eight-percent margin. Bartlett went on to win each of his subsequent nine elections by at least 12 percent. The Cook Partisan Voting Index (PVI), which predicts the depth of a district’s party leanings, rated the 6th district “R+12” in the last election, meaning that a generic Republican presidential candidate could expect to win the district by 12 points.

But last October, the state legislature wrecked Bartlett’s cozy Republican district. In a plan proposed by Governor Martin O’Malley’s redistricting panel and passed by the Democratic-majority General Assembly, the 6th district lost its rural, right-leaning sections of Frederick, Carroll, Baltimore, and Harford counties, and instead had a large chunk of Montgomery County, including heavily Democratic D.C. suburbs like Potomac, added to it. Democrats officially say that the re-districting was the result of new census data. But it’s widely accepted that state legislatures gerrymander districts to maximize a favored party’s seats.

“It’s not personal,” Bartlett says, with a shrug, of the redistricting. “They just needed another Democrat seat. The Democrats only control, I think, six states and the District [of Columbia]. Republicans control, I think, four times that. So they had to find pick-up opportunities anywhere they could.”

Bartlett may be philosophical about the motivations behind the redistricting, but he’s not naïve about the challenge he faces in holding onto his seat. Since the redistricting passed, Maryland’s 6th district has been one of the most hotly contested races in the country—Congressional Quarterly has named it one of the top-ten most competitive—and will help determine which party has control over the House of Representatives. Money has poured into the district from both national parties, and Bartlett himself has been thrust into the largely unfamiliar role of steadfast campaigner.

“This year has been drastically different than anything we’ve ever had before,” Bartlett says, slouching behind his conference room table. “I mean, we’ve never really even had a professional campaign before.”

The competitiveness of the district has brought new scrutiny to Bartlett and his office. The mustachioed congressman was briefly the subject of ridicule earlier this year when a staff member took seriously a mock bill sent in by a group calling itself “The American Mustache Institute,” that called for a $250 tax deduction for facial hair grooming. The staff member sent the bill on to the House Ways and Means committee, apparently without Bartlett’s knowledge, leading to guffaws around the political blogosphere and attacks from Bartlett’s opponents. State Delegate Kathy Afzali, who challenged Bartlett in the Republican primary, said the situation showed that Bartlett had lost control of his staff and “is out of touch with voters.”

In the primary, Bartlett beat back several challengers, including state legislator David Brinkley, who claimed the Congressman was responsible for an e-mail late in the campaign that included audio of 911 calls related to domestic disturbances at Brinkley’s house (Bartlett denies any involvement in the e-mails). But things could get uglier—and even more competitive—in the general election, where Bartlett faces the Democratic nominee, businessman John Delaney.

Delaney, who founded financial services company CapitalSource, has poured more than a million dollars of his own money into his campaign, helping him soundly defeat state legislator Rob Garagiola, who was favored by the national Democratic party, in the primary. He’s proven to be a smart campaigner, repeatedly touting his proven record as a job creator—a crucial selling point in an economy-obsessed electorate.

“We need new leadership,” Delaney says, echoing the concerns of many in the district who think that Bartlett has been in Congress too long, and that he’s too old to conceive of innovative solutions to a complex set of new issues. “I’m an advocate for infrastructure investment, national energy policy, things that I think are important in leading us into the next generation, and I think there just haven’t been those voices in Congress.”

For his part, Bartlett isn’t looking to update his policy agenda or alter his tried-and-true methods in the face of a new campaign reality.

“We had a campaign consultant who wanted to program me,” Bartlett says. “I said ‘It’s too late!’ I’ve been here 20 years, I’ve been saying all this stuff, I have all these votes—I am who I am. If I’m not electable, I’m not electable, but I am who I am.”

A week before the primary election, Roscoe Bartlett is strolling down Frederick’s quaint East Street. Lined with antique shops, cafes, and boutiques, the block oozes the kind of small-town charm that has made Frederick a tourist destination for weary Baltimoreans and Washingtonians.

Bartlett, having carpooled with co-chief of staff Sallie Taylor, slowly walks toward a restaurant, stopping to greet a few passers-by who recognize him. “Hey, Roscoe,” one man shouts.

Bartlett and Taylor are headed toward Shab Row Bistro and Wine Bar, one of the more swanky establishments on East Street, where Bartlett will speak at a lunch hosted by a senior citizen group. Just inside the door, there is a table with place cards. One reads, “Congressman Roscoe,” and underneath, his choice of entrée, “Ravioli.” There is no punctuation or last name, making it seem that the congressman is the hero in a spaghetti western, Roscoe Ravioli. He even looks the part, with his pointed mustache and swoop of white hair.

“It seems no one around here ever uses my last name,” he says, showing off the place card to chuckling reporters. “It’s okay. I like ‘Roscoe.’ It’s a unique name.”

Bartlett spends a half-hour circling the room, talking to each table of guests. Most are in Bartlett’s age bracket, and health issues are a frequent topic of discussion. At one table, a woman is wearing an oxygen mask because she has emphysema. The congressman details his brother’s health struggles and offers encouragement. At other tables, he spends most of his time listening intently.

After a brief break to eat, the congressman stands up and offers his loose version of a stump speech, which echoes the themes of fiscal and personal responsibility he’s hammered throughout his political career, mixed with folksy anecdotes, tangents, and a sampling of quotes from the likes of Winston Churchill and Thomas Jefferson.

“Government is too big—it spends way too much, it taxes too much, it regulates too much,” he says. “We have wandered a million miles from the government our founders wanted.” He underlines the point by quoting Jefferson: “The government which governs best is the government which governs least.”

Bartlett grew up in Depression-era rural Kentucky, where he attended a one-room schoolhouse and endured extreme poverty. “It really changed my life,” he says. “I decided my kids would not go through what I went through.”

He says his political evolution closely mirrors the quote, often attributed to Churchill, “If you’re not a liberal when you’re 20, you have no heart. If you’re not a conservative when you’re 40, you have no brain.”

“When I was a kid, I looked around and saw problems and thought, somebody needs to fix this—there are people really hurting,” he recalls. “I looked for some entity that was big and powerful, and it was the government.”

But, a precocious kid, Bartlett said he wised up ahead of schedule. “I wasn’t 20 before I figured out that government wasn’t the solution,” he says. “It finally dawned on me that government doesn’t have any money. They just take or borrow the money. All the government needs to do is make sure that we have the environment that our founding fathers envisioned.”

Bartlett went on to become the first member of his family to graduate from college, with a degree in biology and theology, and came to the University of Maryland, where he earned a master’s degree in physiology in 1948 and a Ph.D. in 1952. He married Ellen Bartlett and the couple ultimately had 10 kids, including Joseph Bartlett, who was a member of the Maryland House of Delegates for 11 years. The congressman now has 18 grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

In 1961, Bartlett bought his current farm in Buckeystown, and while his career has taken him all over the country, he seems most proud of his work on the farm.

“At one time, I had the largest pure-bred sheep flock on the East Coast,” he boasts, adding that he also had goats and cows, and that, when he was farming full-time, “I personally handled 10,000 bales of hay a year.”

Bartlett’s easy, friendly demeanor and his country background are exactly what have endeared him to the voters in the 6th District for the past 20 years.

“He’s as human as anyone can be,” says Dana Smith, 59, a guest at the Shab Row lunch. “I mean, we’ve seen him in his overalls. You can’t get more real than that.”

And Bartlett’s friendliness extends beyond his constituents. Another way the congressman seems to be of a different era is that he proudly talks about his deep friendships with colleagues on the other side of the aisle. In particular, he’s a close confidante of Nancy Pelosi, the California Democrat originally from Baltimore, who has become enemy number one in the eyes of many Republicans. Bartlett calls her “a very committed woman,” and has accompanied her to the last two State of the Union addresses.

“I hate the partisanship,” says Bartlett. “At the end of the day, we want the same things: We want better schools, we want good jobs, we want safe streets, we want a military adequate to defend out country. It’s just that we have very different ideas about how to get there.”

As Bartlett takes questions at his campaign event, it becomes clear that his friendly attitude toward Democrats is not shared by all of his supporters. One worries that after the election, if Obama wins, he’ll order everyone to turn in their guns. Bartlett, a strong defender of the Second Amendment, deflects the question by criticizing gun-control laws.

A woman wonders if tax dollars are going toward the effort to legalize gay marriage. Another supporter suggests that gay people are being given special marriage benefits unavailable to straight people. Bartlett, who is opposed to gay marriage, says it’s primarily a state issue, but claims that, years ago, he first coined the phrase, “It’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve,” and suggests that legalizing gay marriage may lead to legalized marriage between people and animals.

Bartlett’s peculiar array of positions have allowed him to be the rare GOP congressman on both the Republican Main Street Partnership, a collection of moderate Republicans, and the Tea Party Caucus. “I’m probably the luckiest person in the Congress,” he says. “I vote my conscience. And that, so far, has been okay with the district.”

But observers say Bartlett’s maverick streak might not work in the new 6th District, especially against an outsider like John Delaney.

“His independence probably would’ve helped him more if Rob Garagiola had ended up winning that race,” says Alex Isenstadt, a blogger at politico.com who’s been closely following the 6th district. “It would’ve been easier for him to portray Garagiola, fairly or not, as a creature of Annapolis. Right now, he’s running against John Delaney, who’s an unknown, and it’s going to be harder to brand him as an insider. He’s a job-creator, someone who made millions of dollars in the business sector. It might be harder for Republicans to run against that.”

Lala Mooney is pacing next to her car outside of Frederick County’s Ballenger Creek Middle School. Today is primary day, and Mooney is here to get out the vote for Bartlett, whose campaign stickers cover her bumpers.

“I hope you’ll vote for my guy!” she shouts at voters, as they enter the school gymnasium, and waves two “Elect Roscoe Bartlett” signs.

Mooney, a Cuban-American from Frederick, is the mother of state GOP chair Alex Mooney, who served in the state legislature for 11 years and briefly considered challenging Bartlett for the nomination, but instead threw his support behind the Congressman. Lala Mooney says the redistricting has upset a lot of people in the district and that it motivated her to volunteer for Bartlett.

“It’s been a big issue,” she says. “It’s really skewered the democratic process, eliminating voices that have traditionally been represented.”

She’s confident that Bartlett will pull out the election in November, but admits that the race will be “competitive.” She says local peoples’ resistance to Obama’s agenda will drive them to the polls to vote for Republicans.

“I know that socialism, the way Obama’s pushing it, isn’t going to work,” she says, adding that two Democrats had already told her today that they plan to cross party lines to vote for Bartlett in November. “Government is not going to solve our problems.”

Deborah Lundahl, a local Republican heading out of the polls after casting her vote, agrees with Mooney that the redistricting has upset a lot of people—“it destroyed a rural district, with rural concerns,” she says—but adds that she voted against Bartlett in the primary. “He promised to run for two terms, then step down,” she says. “The longer he stays, the more he seems like just another politician.”

It’s a feeling that seems to have some resonance in the district. Many expected Bartlett to step down after the redistricting and allow a younger Republican to take up the challenge, but he has soldiered on, seeking his 11th term in office.

“It’s going to be a tough race for him,” says Isenstadt, who thinks Delaney will come out on top in November. “It’s tough for a guy in his mid-80s, who’s been around for as long as he has, to run in a new district, let alone one that’s very Democratic.”

Indeed, most analysts now say the district “leans Democratic” and Capitol Hill newspaper Roll Call has listed Bartlett among the 10 most vulnerable members of Congress. “It’s possible that all of the ingredients could come together for Bartlett . . . to pull off a win,” they wrote in March. “But it just doesn’t seem plausible at this point.”

For his part, Bartlett says if he loses in November, it’ll give him more time to spend on the farm, where he still keeps a garden and some cows. “We’re trying very hard to get acquainted with the new members of the district,” Bartlett says. “If it doesn’t happen in time for November, so be it. I am who I am.”