Why you can’t get there from here, but maybe you can soon The Lost Subways of Baltimore

“Baltimoreans could seriously ponder the question of whether the city is more important to live in, or race through.” —James Dilts, March 3, 1968, The Sun

It’s no secret Baltimore’s mass transit system is a mess, but exactly how bad is it? Based on a 2016 study using U.S. Census data and the American Public Transportation Association’s Ridership Report, Baltimore ranks 24th among 25 major cities in terms of our average transit commute time. (Thank you, Newark for being last.) When you combine the overall efficacy of public transportation—that’s transit versus driving and other factors—Baltimore pulls in at 19th, one spot behind notorious car-centric Los Angeles.

So, how did we get to this? In the late ’60s and early ’70s, James Dilts, staff writer for The Sun, wrote a column called “The Changing City,” tackling the sweeping urban issues of the day including housing, poverty, and transportation. “That was when the Charles Center got built,” recalls Dilts, who currently serves as The Peale Center’s board president. “It was a time of hope.”

Re-reading those columns can be disheartening a half-century later because the same intractable problems remain. Yet, Dilts’s reporting on the era’s massive highway build-up and the lack of a viable mass transit agenda is instructive in hindsight, explaining much of the present state of Baltimore’s poor public transportation system and traffic woes. In a January 1969 column, “A Question of Roads or Rails,” Dilts writes the only real solution to relieve congestion into Baltimore’s business districts is mass transit, noting “expressways create as much traffic as they distribute, and are, therefore, obsolete in a relatively short time.”

Before Gov. Larry Hogan cancelled the Woodlawn to Bayview, 14-mile Red Line initiative last year, the late ’60s and early ’70s were the last opportunity to build a comprehensive subway/rail/bus system. (Inexplicably, Baltimore missed its first opportunity at the turn of the 20th century—despite complaints of “congestion” as far back as 1905—when New York, Boston, Philadelphia, and European cities built subways as electrical lines were placed underground.) That failure has reverberated through the decades, leaving Baltimore with a disconnected system that doesn’t just reflect the city’s inequality, but has perpetuated it—studies have correlated a lack of reliable transit to unemployment in lower income neighborhoods.

The impediment to a subway system, Dilts says, was a lack of consistent planning and political will. “Plus, you had real pushback in Baltimore County and Anne Arundel County, with people complaining that a subway would bring crime,” he says. Not only is ridership here roughly 25 percent less than Philadelphia; half of Washington and Boston; and a third of New York—the income gap among users is dramatically different. In New York and D.C., ridership reflects the overall population—the difference in median income for the entire city and transit users is negligible, 2 or 4 percent. Baltimore’s income gap is 35 percent—making the system one of the most class-segregated in the U.S.

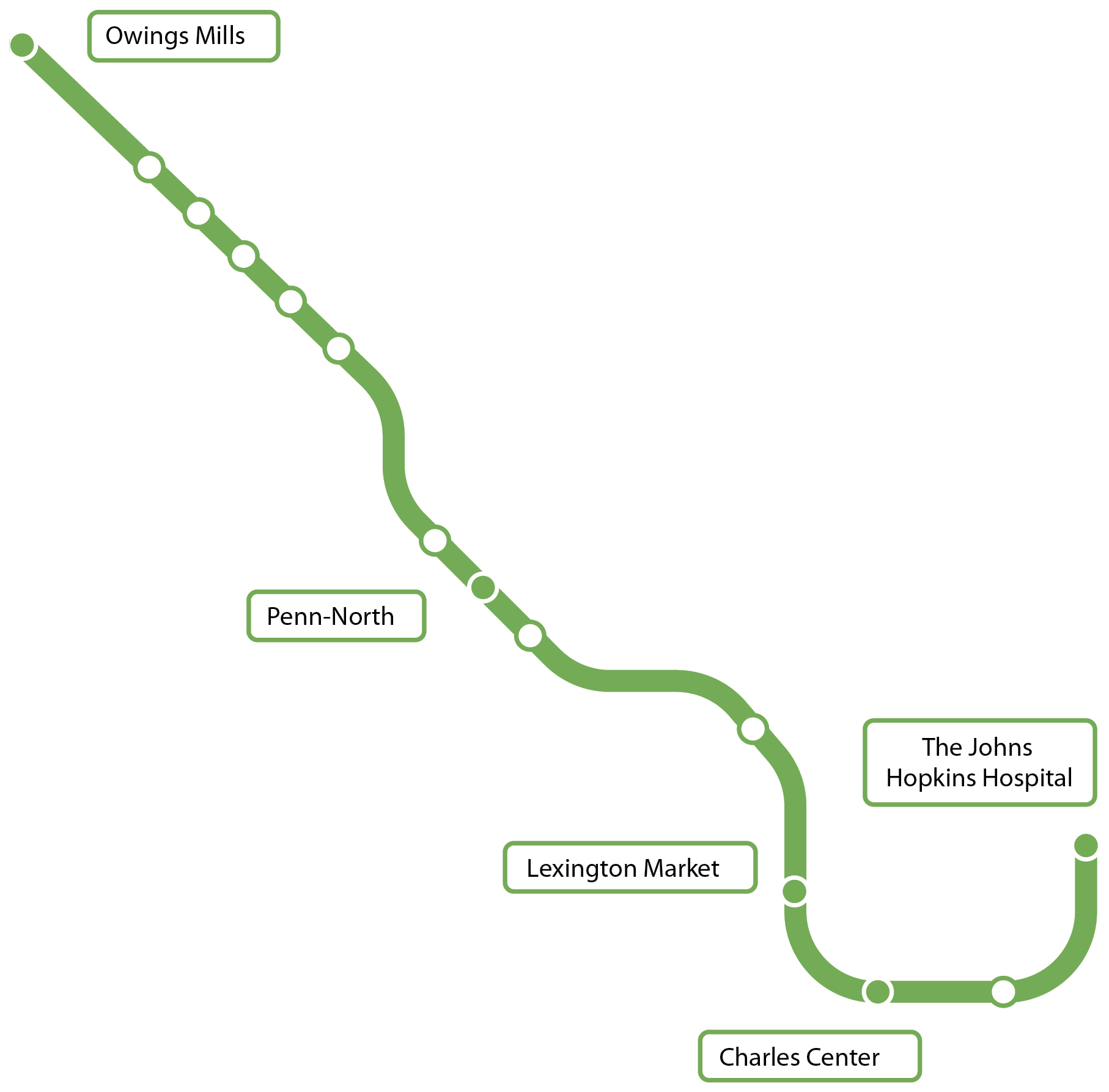

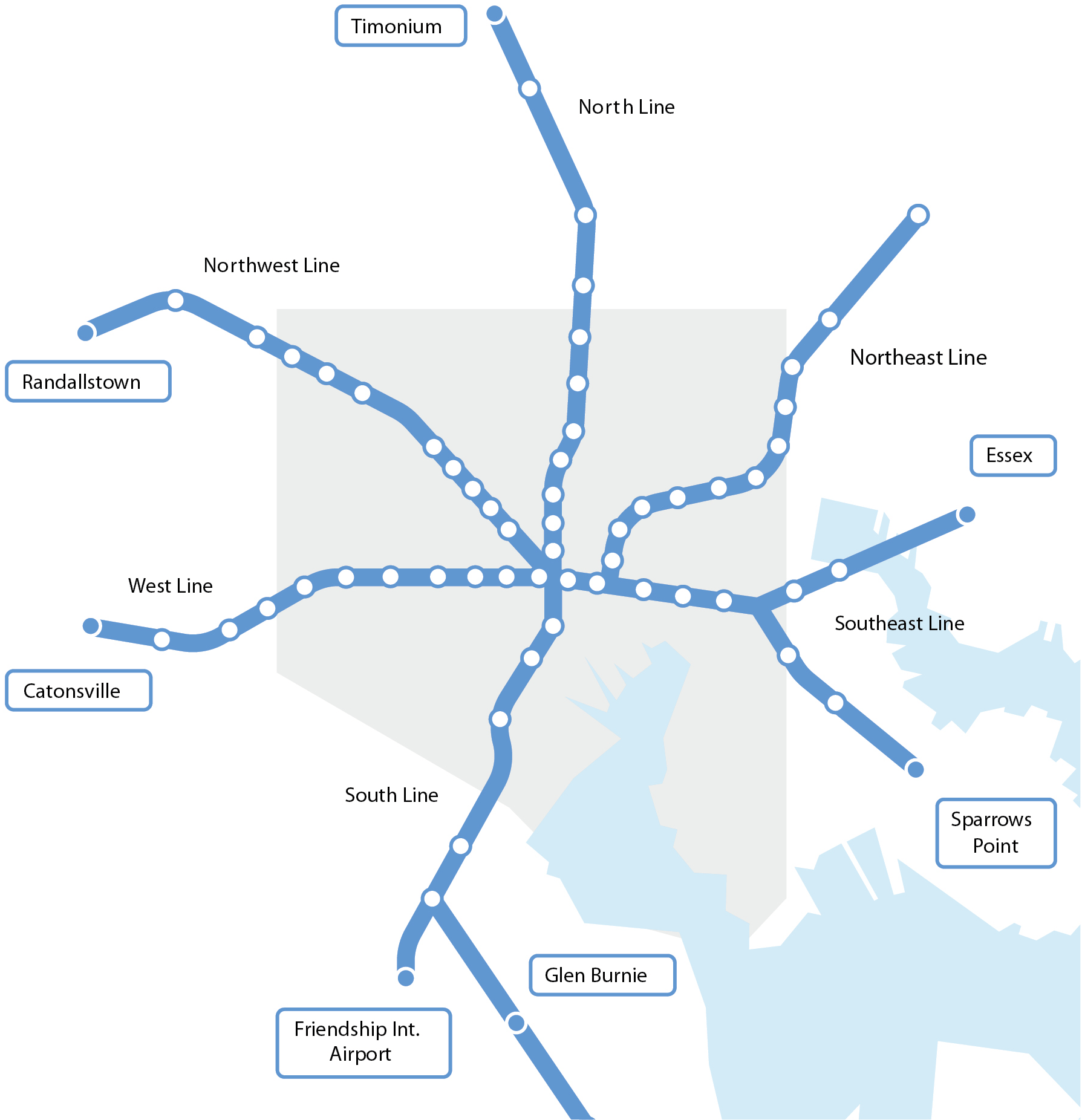

▸ A 1968 design for a Baltimore subway system.

By the time the designs (see 1968 map) for an integrated subway and rail line and proper commissions were set up to move forward with a proposed 71-mile, 63-station hub system, federal money dried up as the country sank into the economic straights of the 1970s—caused, ironically, by the first oil embargo. Ultimately, just the single, Owings Mills to East Baltimore line opened in 1983. In 1992, the light rail line from Timonium to Baltimore/Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport was added, mimicking two of the lines on the 1968 map, but not in an integrated way.

“Baltimore ended up with a kind of mixed-up system of subway lines, rail lines, and bus lines that don’t connect well. There are just a lot of places you can’t go,” Dilts says. “Not easily, at least.”

With all that said, the Maryland Transit Administration is in the midst of overhauling Baltimore’s bus system, the city is launching its bike-share program this fall, and construction has started on a downtown bike network. Ride-sharing companies are also providing more options. Meanwhile, several new nonprofits—Transit Choices, Bikemore, and the Baltimore Equity Transit Coalition—have formed to help push transportation in the city into the 21st century. Over the next seven pages, we detail the coming changes and transportation options. Maybe it’s a time of hope again.

The Multi-Modal City The Year of the Bike

After numerous fits and starts, Baltimore will launch its bike-share program this fall. The system will begin with 250 bicycles at 30 stations—half of which will be electric pedal-assist bikes. Ultimately, 465 bikes at 50 stations should be in place by spring from Locust Point to Station North. Equally important, the Department of Transportation has started construction on the Maryland Avenue cycle track—a dedicated, two-lane bikeway protected by flex posts—and a downtown network of bike lanes. With these projects as well as a build-out of street infrastructure—bike lanes and racks, protected cycle tracks, and the extension of the Jones Falls Trail, for example—2016 could prove to be a great leap forward for bike commuting in Baltimore.

Bike Share By the Numbers

What is bike share? It’s a public transportation system—first begun in North America in Washington, D.C., in 2008—that provides convenient, safe, inexpensive bikes for short trips. Users pay daily or monthly fees.

$2 Baltimore’s planned per-trip fee (up to 45 minutes)

$60 Monthly Capital Bikeshare commuter cost savings

$15 Baltimore’s planned monthly membership

390 Stations in the Capital Bikeshare system

56 U.S. cities with bike-sharing systems

3,500 Bikes in the Capital Bikeshare system

Build it and they will come Downtown Bicycle Network

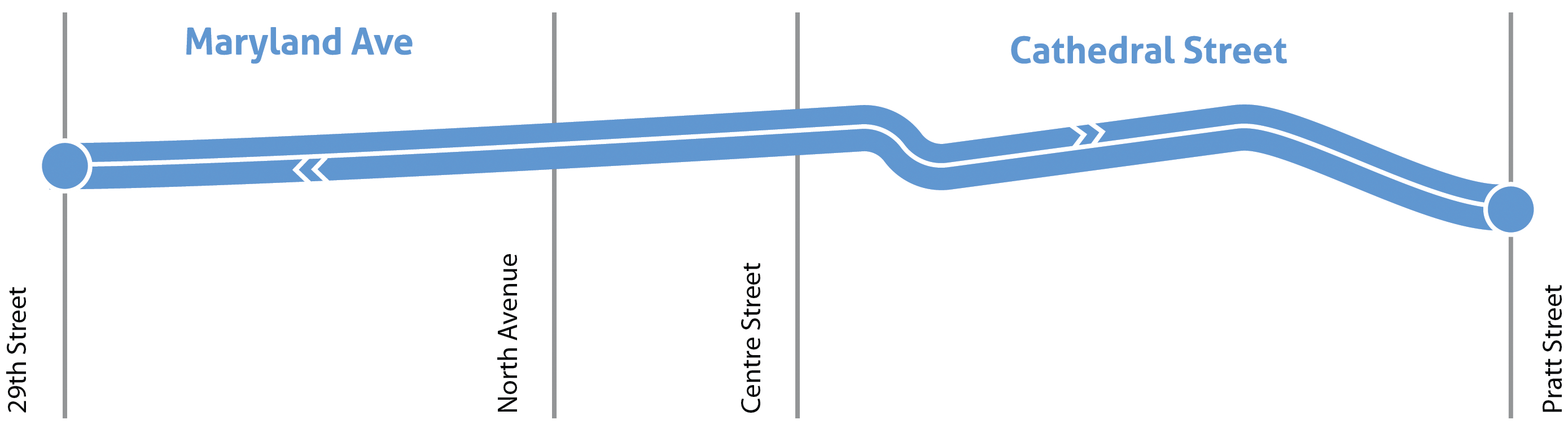

When polled, more than half of potential bike commuters say they’re interested, but concerned about safety. It’s why projects such as the Maryland Avenue

cycle track and downtown bicycle network are viewed as critical to boosting the number of Baltimore bike commuters. Stretching from the Baltimore Museum of

Art to Pratt Street, the Maryland Avenue cycle track will soon provide a dedicated, two-way lane for cyclists protected by flex posts. The north-south

route will connect with painted bike lanes on east-west Preston, Biddle, Madison, and Monument streets—as well as the already established north-south,

Fallsway/Guilford Avenue cycling lane. Eventually, the network will expand, connecting to lanes in East and West Baltimore.

Pictured from left: Jay Decker, city bike-share coordinator; Veronica McBeth, transit bureau chief; and Caitlin Doolin, bike and pedestrian planner.

Unveiled last year by the city's Department of Transportation, the new bike master plan calls for a network of 253 miles of bike lanes, trails, protected tracks, and facilities over the next dozen years, with a goal of boosting bike-commuting rates toward 8 percent. “I’m optimistic. There’s a lot of good planning in place and funding,” says Liz Cornish, executive director of Bikemore, the city’s nonprofit bicycling advocacy organization. “The next critical step is that we need the new mayor to appoint a city DOT director [former director William Johnson resigned in April] with a vision for ‘complete streets.’”

As of 2015, Baltimore had more than 160 overall miles of bike lanes. “I think our story is going to be very aggressive growth in bicycle commuting over the next five years,” says Jay Decker, Baltimore’s bike share coordinator and a Butchers Hill car-free bicycle commuter.

The Maryland Avenue cycle track—a dedicated, two-lane bikeway protected by flex posts.

The Multi-Modal City Start the Bus

Everywhere a Sign: The MTA is creating new bus stop signs, maps, and vehicle branding. The new MTA bus stops will be more clear and easy to use, and in addition to the the newly designed signs and maps, the agency will also be developing strategies to help the rider find their way once they step off the bus.

Four months after Gov. Larry Hogan cancelled the city’s planned $2.9 billion Red Line rail line last June, he unveiled a $135 million proposed overhaul of the Baltimore-area bus system, which is run by the Maryland Transit Administration. In making the announcement, Hogan described the transit network as “a mess,” which certainly seems to be the consensus among both elected officials and riders. The best news? When rollout is complete next summer, the MTA says the changes will provide high-frequency bus access to 34,400 more jobs—a 14 percent increase over the existing system.

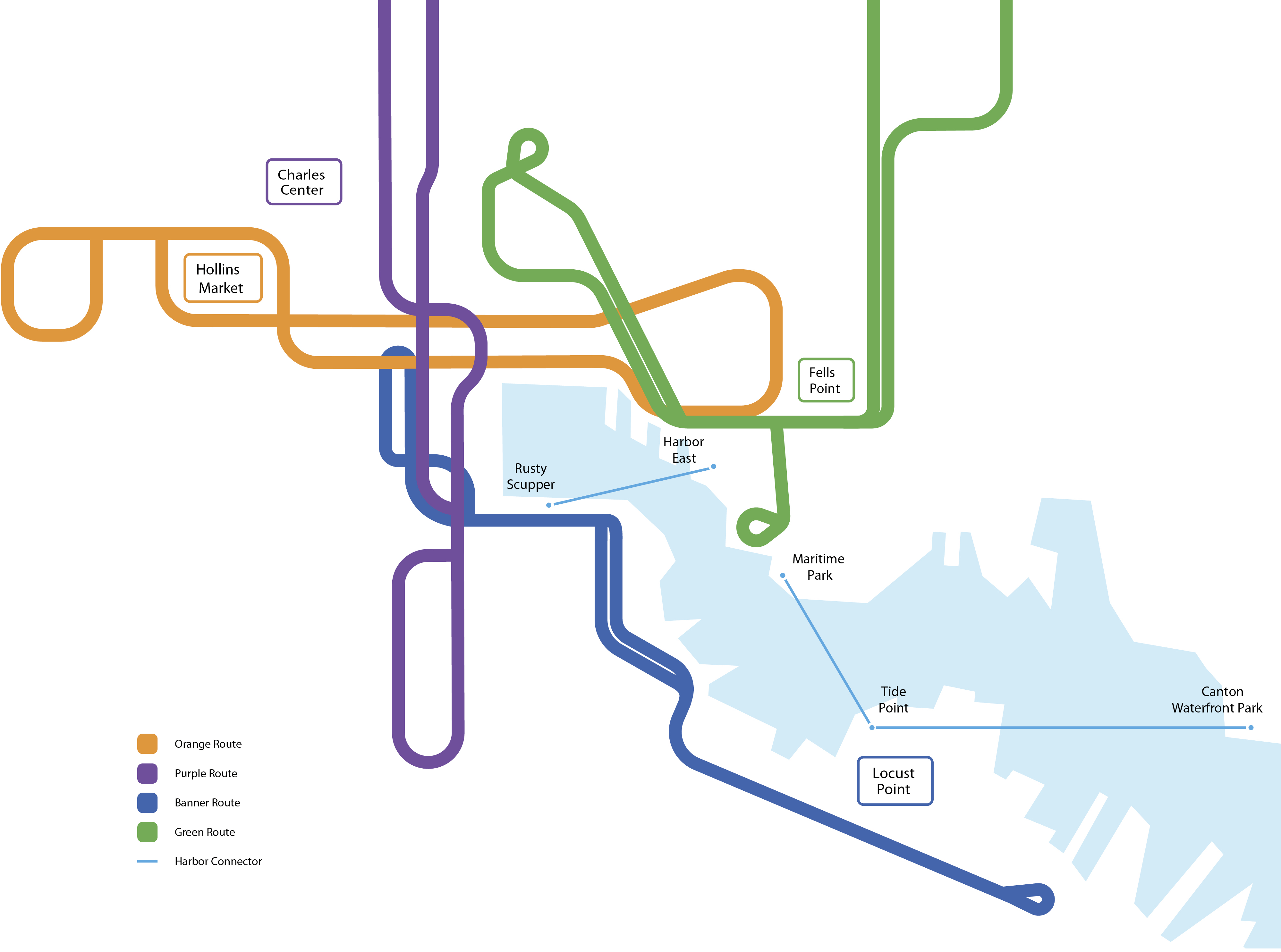

Two key components of the Maryland Transit Administration’s new local bus plan—known as BaltimoreLink—are re-working the current routes to improve reliability and implementing a dozen new color-coded, high-frequency lines. One of the most basic changes involves reducing bus exposure to the daily congestion around the City Hall area, by shifting downtown street routes. More than 800 buses a day, for example, currently are required to navigate the crowded traffic on Baltimore Street. After dozens of briefings and 20 public workshops across the city and adjacent counties, the MTA has been widely praised by transit advocates for its receptiveness to public input. But whether a six-year investment of $135 million—which includes a major re-branding of local buses, signage, and stops, as well as dedicated, red-painted bus lanes—is enough to transform a failing system remains to be seen.

Edward Cohen, a longtime accessible-transit advocate and former chairman of the MTA’s Citizens Advisory Committee, says the MTA deserves credit for re-examining its outdated network of routes—a process that actually began several years ago. But Cohen says the purchase of a relatively small number of new buses and addition of 50 new drivers isn’t enough. “We have an overcrowded system,” he says. “What’s needed is more capacity.”

Curtis Bay - Station North

Lutherville/Towson - Inner Harbor

Towson - West Baltimore MARC

Turner Station - Penn-North

CCBC Essex/Cedonia - West Baltimore MARC

Rolling Rd & Rt. 40/Paradise Loop - Penn Station

White Marsh/Overlea - West Baltimore MARC

CMS & Security Square/1-70 Park & Ride - Bayview

Fox Ridge / Bayview - West Baltimore MARC

Halethorpe MARC / Kaiser Medical - Broadway North

CCBC Catonsville - Broadway North

Randallstown - Fells Point

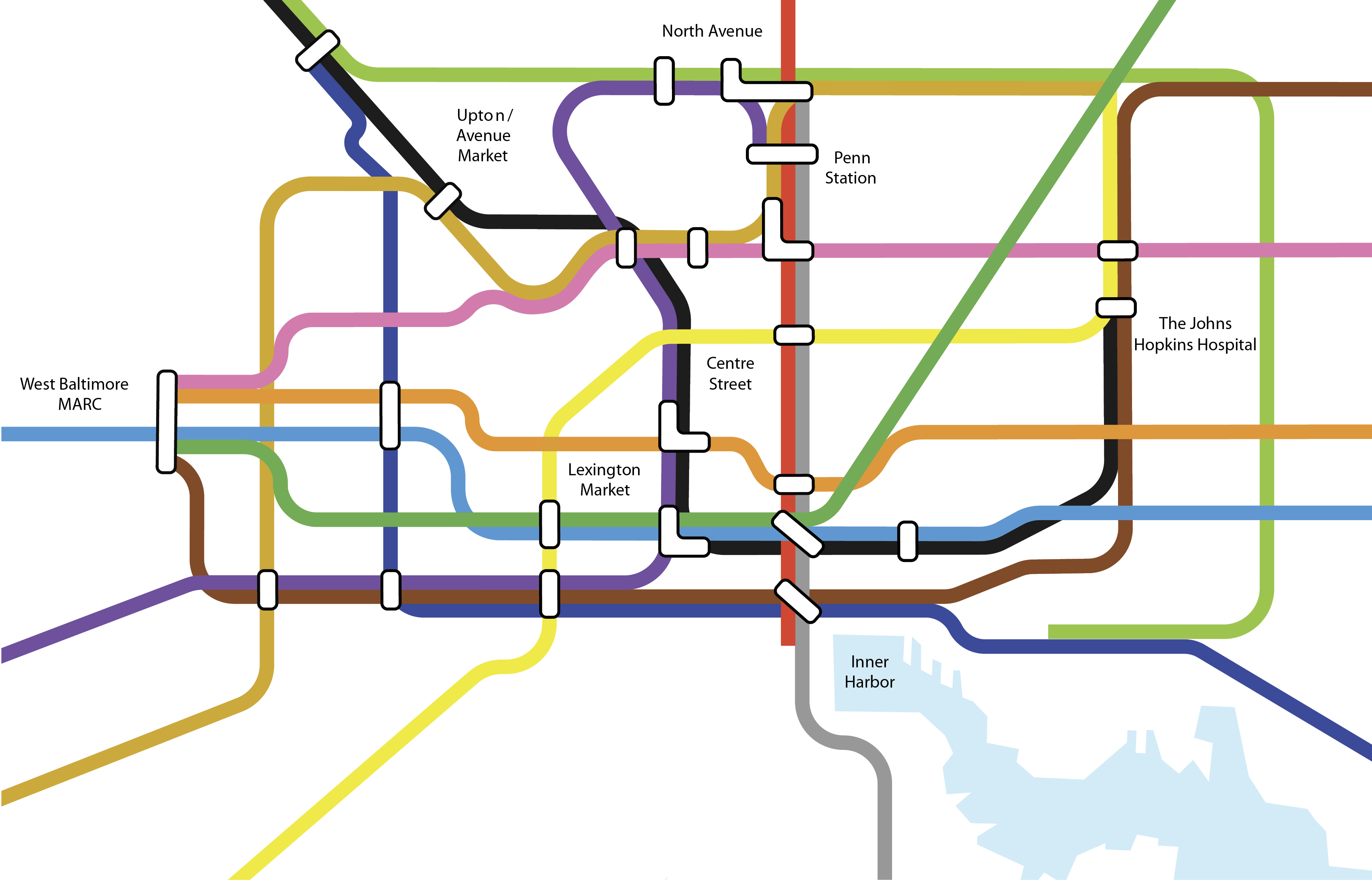

▸ Local Link: The new, high-frequency, colored-coded CityLink service will connect to the subway, light rail, MARC and Amtrak trains, suburban buses, and other services. Integrated into that network will be LocalLink buses that will offer regular, and more traditional MTA-type scheduling into neighborhoods not directly served by CityLink

The city’s long, east-west corridor, North Avenue, will begin a $27.3 million transformation in 2017. North Avenue Rising

In late July , the U.S. Department of Transportation approved Baltimore’s $10 million TIGER (Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery) grant application to fund the North Avenue overhaul, which also includes almost $15 million in state money along with city and other federal support. “After decades of lack of investment, North Avenue and the surrounding communities will get the long-overdue attention they deserve,” Gov. Larry Hogan said in a statement.

The project, titled North Avenue Rising and part of the Maryland Transit Administration’s BaltimoreLink initiative, will create dedicated bus lanes and shared bus and bikes lanes, and will repave the road. It will also enhance bus stops and street lighting, and improve bus-signal prioritization and nearby Metro Subway and light rail stations.

The hope is that the North Avenue Rising project will boost economic activity along the corridor while improving access to jobs and various institutions for local residents. Liz Cornish, executive director of Bikemore, says the effort is needed, but the design can be made better. “Our concern is the bike/bus shared lane and sections where the bike lane gets broken up,” Cornish says. “There’s plenty of space [for a dedicated bike lane] . . . and then a five-minute bike ride would connect a lot of people to Penn Station, light rail, and the subway.”

The Maryland Transit Administration’s $135 million, six-year investment is targeted to improve access to employment, colleges, and government centers. It’s also intended to foster bicycle use and car-sharing connectively. Last fall, as part of BaltimoreLink, the MTA announced that bicyclists can now take their bikes on all Maryland Area Regional Commuter (MARC) Penn Line weekend trains between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. The new bike cars allow riders to bring full-size, noncollapsible bikes onboard and secure them in one of 23 racks. There is no extra charge, and racks are available on a first-come, first-served basis. »

BaltimoreLink, when fully implemented, will:

The Maryland Transit Administration’s $135 million, six-year investment is targeted to improve access to employment, colleges, and government centers. It’s also intended to foster bicycle use and car-sharing connectively. Last fall, as part of BaltimoreLink, the MTA announced that bicyclists can now take their bikes on all Maryland Area Regional Commuter (MARC) Penn Line weekend trains between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. The new bike cars allow riders to bring full-size, noncollapsible bikes onboard and secure them in one of 23 racks. There is no extra charge, and racks are available on a first-come, first-served basis.

Implement 12 CityLink high-frequency, color-coded bus routes serving downtown Baltimore

Equip 200 key intersections with transit signal priority to improve timeliness

Add bicycle racks to 36 MTA rail stations, which currently don't have bike racks

Ensure all MARC weekend trains between Baltimore and Washington, D.C., include bike cars

Implement at least 20 targeted car-share locations at MTA rail stations in the Baltimore region

Wrap buses in BaltimoreLink colors—the familiar red, white, yellow, and black of the state flag

The Multi-Modal City Riding the Rails

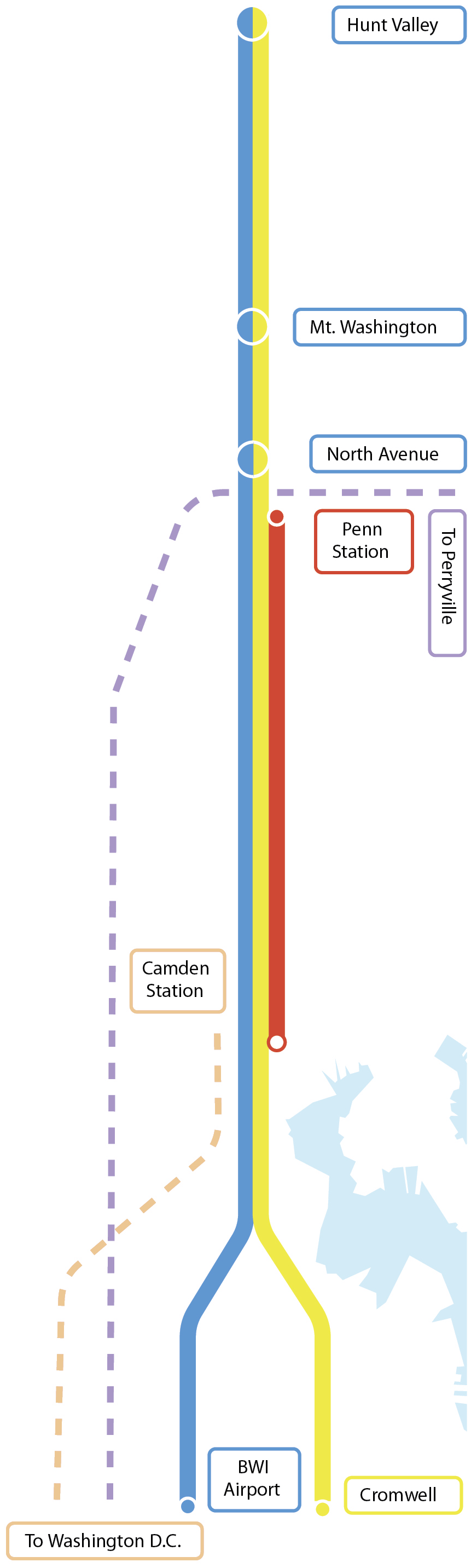

▸ Baltimore Light Rail and MARC View Larger

The same month the Orioles played their first game at Camden Yards—April 1992—the light rail line opened for business, connecting northern Baltimore County to the downtown ballpark. Though not a hit initially—the light rail attracted fewer than 10,000 riders each day that first year—those numbers got a jolt when the All-Star Game came to town the next summer, and then Pope John Paul II visited Baltimore and held mass at the ballpark in 1995. In 1997, light rail extensions opened in Hunt Valley, at Baltimore Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, and at Penn Station, and then on Hamburg Street after the Ravens moved into their stadium. The system has limitations, but it’s efficient, posting a 97 percent on-time record. By 2013, average weekday ridership was up to 27,537 and annual ridership surpassed 8.6 million. The same year the light rail opened, the Maryland Transit Administration assumed control of the MARC (Maryland Area Regional Commuter) train, which has three long commuter lines—Camden, Penn, and Brunswick—that trace their origins to 19th-century railroad routes. The MARC, of course, serves Baltimore’s D.C. commuters.

North-South Line, But Not East-West New Fight for the Red Line

Before Gov. Larry Hogan cancelled the project, the decade-in-the-works, $2.9 billion, 19-station Red Line was supposed to not just connect East and West Baltimore to Woodlawn in Baltimore County, but also serve to connect the light rail and subway systems. Much of the Red Line route traced part of the 1960s subway designs, when Baltimore leaders instead pushed for the east-west, urban expressway known as The Highway to Nowhere, which displaced hundreds of West Baltimore residents. “The Road to Nowhere broke up West Baltimore communities that are still trying to recover two generations later,” says Glenn Smith, 67, a member of the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition and signatory to a citizen complaint filed with the U.S. Department of Transportation over the Red Line's cancellation. “My family was one of those displaced. Those 19 stations along the Red Line would’ve brought considerable investment to the community.” Smith notes that studies show long mass-transit commute times are linked to unemployment in low-income neighborhoods. The NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund has filed a federal civil rights complaint, alleging Maryland discriminated against black residents when Hogan cancelled the Red Line and sent state money instead to road, highway, and bridge projects in other parts of Maryland.

Port Covington: Recently, as part of its Port Covington proposal, Under Armour’s development arm pitched a southern light rail spur to connect to the waterfront project. Water-taxi stops and bike-share stations are also part of the massive, 260-acre, estimated $5.5 billion initiative, which won approval from the city planning commission in June. The City Council, however, is still debating the project’s controversial public financing proposal.

Gov. Larry Hogan unveiled a $135 million proposed overhaul of the Baltimore-area bus system, which is run by the Maryland Transit Administration.

The Multi-Modal City Baltimore Metro Subway

The 15.5-mile, 14-station Baltimore Metro Subway first opened in 1983 with the Charles Center-to-Reistertown Plaza section, expanding to Owings Mills four

years later and The Johns Hopkins Hospital in 1995. Most of the line is actually above-ground, but it all delivers in terms of efficiency, posting 97

percent on-time performance systemwide. Although vastly under-used—essentially because it’s a single line that doesn’t connect directly to the light rail

or MARC trains—the subway carries more than 45,000 people daily. The 77,000-pound, 75-foot trains travel roughly 1 million miles annually.

This summer, crews installed new devices to assist subway trains crossing from one track to another, replaced old rails, and cleaned stations.

The Line

The Metro Subway system operates every eight-10 minutes during the morning and evening peak periods; 11 minutes on weekday evenings; 15 minutes on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays.

The Upgrades

The system was partially shut down this summer for a $16-million repair project. Although there have been legitimate complaints about working conditions by Metro Subway employees, the subway generally receives solid marks from users.

The Free Parking

The Johns Hopkins Hospital, Shot Tower/Market Place, Charles Center, Lexington Market, State Center, Upton/Avenue Market, and Penn-North stations do not offer free parking, but others do:

▼

Mondawmin; West Cold Spring; Rogers Avenue; Reisterstown Plaza; Milford Mill; Old Court; Owings Mills

THE SERVICE: Owings Mills to The Johns Hopkins Hospital

Weekdays: 5 a.m. to midnight. Weekends: 6 a.m. to midnight. >>

THE FARES

One way $1.70,

Day pass* $4,

Weekly pass $22,

Monthly pass $68.

(SENIOR/DISABILITY)

One way $0.70,

Monthly pass $20,

Day pass* $2.