The Johns Hopkins University sociologist Karl Alexander had come to Baltimore in the early 1970s with an interest in high-school graduates and their transition into the “real world.” By 1982, however, he was squeezing his 6-foot-4 frame into pint-sized chairs at 20 public elementary schools across Baltimore City, on to something entirely new.

Doris Entwisle, an accomplished colleague whose career pursuits ran toward early education and childhood development, had gotten to know Alexander shortly after his arrival, asking him to help her edit an academic journal. The first female professor to eat in the exclusively male Hopkins Club, Entwisle was not afraid of breaking new ground and, soon enough, a marriage of sorts between their areas of expertise emerged. “It was a simple idea,” says Alexander of what became known as the Beginning School Study, one of the most important longitudinal research efforts of the 21st century. “It was our intuition that if kids got off to a good start in school, things would continue to go well for them. But if they got off to bumpy start, it would likely have a chilling effect over the long haul.”

Initially, the plan had only been to track students’ progress through the third grade. “Then, it dawned on us that we’d done the hard part,” Alexander explains, with a chuckle. “We’d gotten permission from parents, teachers, and the school system, including access to school records. Why not keep going?”

Huddling with first-graders in empty classrooms and over cafeteria lunch tables—wherever schools could find space—the researchers asked some basic questions: “What do you want to be when you grow up?” “What kind of grades do you think you’ll get?” “Do you like school?”

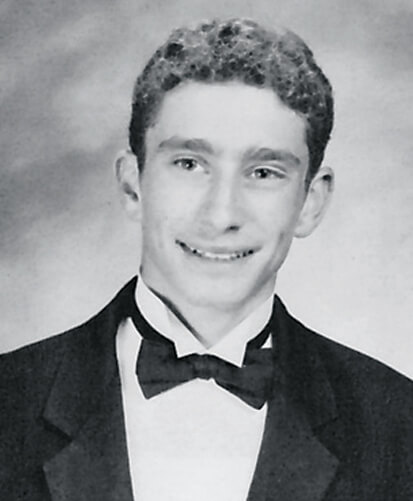

In hindsight, it seemed astonishing that so little research had been done on the transition from “home child” to “school child,” says Alexander, an outgoing, energetic, fatherly 68-year-old with clear blue eyes and a neatly trimmed white beard. “Sociology was focused on all the other major life transitions: High-school graduation, marriage, children, retirement, and aging. No one was looking at the first major transition in someone’s life, which is going to school.”

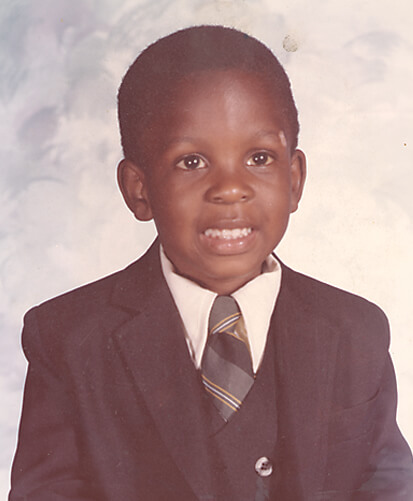

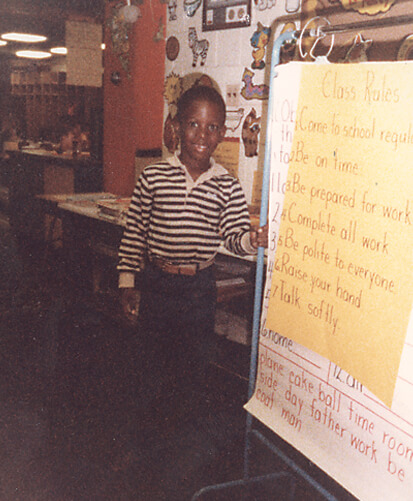

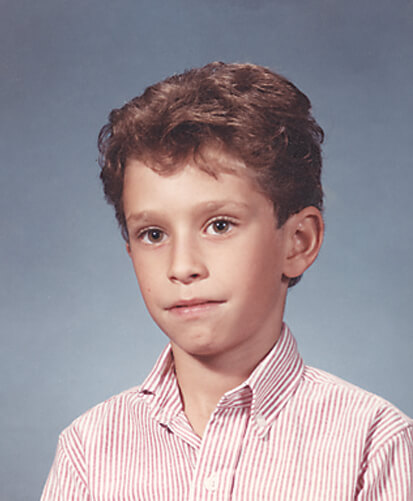

Qwan Finch, of West Baltimore, with his two sons and as a Beginning School study participant in elementary school.

Alexander, Entwisle, and their tight-knit team of researchers would ultimately keep close tabs on 790 first-graders until they turned 28 years old—a feat unlike anything else ever attempted in the United States. The Long Shadow, their acclaimed book based on the study, was published last year, though Entwisle, who passed away at 89 in 2013, did not live to see the culmination of their work in print. As the kids matured into teenagers, the team’s queries evolved to include questions about drug use, relationships, and sex, as well as job prospects and higher-education goals. They talked with the students’ parents once a year, often making home visits, and later recorded extended interviews with students, who would occasionally cry as they looked back and reflected on their lives. Inevitably, the researchers trailed their subjects to juvenile detention centers and, later, to state prisons for interviews with the former first-graders. They also saw many of them start to raise their own children while still teenagers.

“We literally watched these kids grow up,” Alexander says. “It became our life’s work.”

At its core, the Beginning School Study— which largely included, but was not limited to, disadvantaged city kids—set out to determine who succeeds and why. Alexander, Entwisle, and Linda Olson, who started as a research assistant and ultimately served as co-author on The Long Shadow, examined each student’s family and socioeconomic background. Twice each school year, they charted their progress, eventually chronicling their entry into the workforce, and identifying patterns around who landed good-paying blue-collar jobs or completed college degrees, and who struggled to find a toehold. But the broader context matters, too. As these kids entered first grade in 1982, U.S. cities, including this one, were collapsing. More than 150,000 people had fled Baltimore for the suburbs since mid-century and another 150,000-plus would soon be on their way out. Bethlehem Steel, which had once run the world’s largest steel mill at Sparrows Point, was reporting nearly $1.5 billion in losses, and laid-off workers at Broening Highway’s General Motors plant were protesting outside the factory. The War on Poverty had morphed into the War on Drugs, and Mayor William Donald Schaefer pleaded with Congress to stop cutting federal funding to cities.

The subjects’ childhoods would also span the crack and AIDS epidemics, and by the time “the kids,” as Alexander still refers to them, reached high school, Baltimore homicides had peaked at a record 353 a year. “It was not a pretty picture, and it got less so over time.” Alexander says. “Cities, as a rule, do not shrink gracefully. Neither do urban school systems.”

Unfortunately, the issues tackled in the study would prove prophetic. The de-industrialization script continues to play out in large swaths of Baltimore, even as parts of the city are now gentrifying. More relevant than ever, the study’s data, personal stories, and conclusions get to the heart of seemingly every domestic headline today, from the growing inequality-gap and living-wage debates, to racial profiling, marijuana decriminalization, school reform, rising college costs, and stagnating social mobility.

On a chilly night this winter, Alexander, Olson, and longtime staff members Joanne Fennessey and Anna Stoll—a pair of sharp, sweet-natured, 4-foot-11 women in their 60s who became quasi-private detectives for all their chasing down of participants—gathered for a post-publication, celebratory dinner at One-Eyed Mike’s in Fells Point with a small group of study’s subjects. The “kids” are now 38 and 39 years old—it took a decade to complete The Long Shadow—roughly the same age Alexander was, and a just a few years older than Fennessey and Stoll were, when the study launched. The faces have changed and aged over time, but the mood is warm and friendly. The participants still recall the early questionnaires and the more in-depth later interviews.

They also remember the annual birthday cards, although they only just learned the secret motivation behind those hand-written missives—to help the researchers maintain up-to-date addresses. “We knew if they bounced back, somebody had moved,” says Stoll, with a smile as she looks around the table. “That’s also why we always asked for the name and contact information for a family member or close friend, someone besides the parents, who would always know where the kids would be.”

“Oh, I remember the birthday cards,” says study participant John Houser III with a laugh, a beer in his hand. “I thought it was neat every year. I thought, ‘These people care about me.’ It was a genius idea.”

Houser also recalls the gift cards to record stores like Sam Goody that researchers gave away after interviews when he was a teenager. “Ten bucks,” he says, sitting next to fellow participant Jesse Fask, who nods his head of dreadlocked hair. “Enough to buy a CD or cassette tape in those days.”

After growing up in Southwest Baltimore’s working-class white enclave known as Lumberyard, Houser—a graphic designer who graduated from Frostburg State University (“I chose the farthest in-state school from Baltimore”) with the assistance of Pell grants and student loans that he’s still paying off—certainly counts among the study’s success stories. Of the 30 or so kids he grew up with, several were into hard drugs by 18 and 19, including one friend who died from drugs. Just six or seven finished high school, and he’s the only one who went to college. “Most of us started smoking pot around 14, there was a lot of that around—the hard drugs started coming in when we were around 16,” Houser says. “You’d see junkies hanging around the neighborhood, stealing things, and crack was coming in. I saw children, basically, dealing drugs to kids’ parents and kids’ mothers turning to skeletons and turning tricks.”

Houser, who has read The Long Shadow and is anxious to talk about the results with the study’s authors, says he only smoked pot, deciding at some point to distance himself from the lifestyle he saw swallowing up his friends by hiding out in his bedroom, listening to music, and reading comic books. He also recognizes that while his family was occasionally on welfare—his father was a union sprinkler fitter and on strike from time to time—he had two parents and other relatives nearby keeping him on track. “It made me realize, even before I had my own kid, I had parents who cared and parents who wanted to be parents.”

We literally watched these kids grow up. It became our life’s work.

At first glance, the takeaways of Alexander and Entwisle’s research may not be all that surprising—but that’s at least partly because so much of what we commonly know today about disadvantaged kids’ academic achievement actually came from their study. Their most significant finding is the extent to which the study’s first-graders have remained rooted in their socioeconomic birthplace, says University of North Carolina sociologist Glen H. Elder Jr., an expert in longitudinal studies. Educational opportunity, often portrayed as the great equalizer, turns out to be the great separator.

Only 4 percent of the disadvantaged students in the study went on to earn a four-year-college degree, despite many expressing a strong desire—and making numerous efforts—to pursue higher education. Contrast that figure to the 56 percent of the better-off public-school students in the study, who benefitted from a greater wellspring of resources and earned four-year degrees.

And consider this snapshot: Seventeen of 18 black first-grade males in the study from the poorest of the 20 elementary schools had been arrested—mostly for drug possession and/or distribution, but also for more serious charges—by their 28th birthday, with seven of those adult interviews conducted in jail or prison. Seven of the 18 had dropped out of a high school, only five had been employed continuously for two years or more by the age of 28, and only one had earned a four-year-college diploma. (For racial comparison, eight of the 14 white males at the same school had arrest records. By no means a small number, but not nearly the same percentage, either.)

“The obstacles, which start with poorer children before they enter school, build up over time until they are overwhelming,” says Elder, noting that the study was among the first to document the powerful, cumulative effect of summer learning loss among disadvantaged kids. “At first, it’s things like falling back during the summer breaks, and then it’s often a combination of family, personal, and financial issues that prevent them from completing even a community-college degree.” In fact, the percentage difference between low-income college graduates and high-income college graduates in the United States widened over the course of the students’ lives.

In terms of who succeeded in landing good-paying blue-collar jobs, it was race and “the subtle legacy of Jim Crow,” as Alexander calls it, that continued to play a major factor. Manufacturing, construction, and port-related jobs have shrunk since the post-World War II boom, but they still exist. The issue is who gets them and the answer in Baltimore is working-class white men. The discriminating mechanism, researchers found, is a much more connected network for disadvantaged urban white males—family, friends, word-of-mouth—that prevails, enabling them to get their foot in the door and into the skilled trades.

Jesse Fask, who grew up in Mt. Washington, attended Baltimore City Public Schools and became a social worker in the city.

White males from low-income backgrounds ended up with three times the number of good-paying, blue-collar jobs—even as they reported the lowest graduation rates and highest rates of marijuana use, hard-drug use, and binge drinking.

Black women didn’t fare any better compared to their white counterparts, who benefitted by partnering with blue-collar white males, lifting overall household income. With little to look forward to, in terms of college, a consequential career, or financial success, low-income disadvantaged young black women, in particular, had children earlier and reported finding satisfaction and meaning as mothers.

“There’s the popular American ethos, if you work hard enough, you can pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” Alexander says. “Well, that’s true in extraordinary circumstances, but it’s not a level playing field. We’ve fallen behind the vast majority of industrialized countries in social mobility.”

In another sense, past the broad brushstrokes, the two-decade-plus study also presents a nuanced portrait of Baltimore. How did the city, its neighborhoods and schools, as well as the kids’ lives appear to researchers? How did the kids understand their circumstances as they grew up?

In conversation later with those gathered at One-Eyed Mike’s, the subject turns to privilege. “I can clearly remember in middle school when white kids started smoking pot and binge drinking, it was the black guys who were like, ‘That stuff is going to ruin your life,” says Fask, who grew up in a white, middle-class family in Mt. Washington and became a social worker. After elementary school, he attended majority black schools, giving him a unique perspective on stereotypes and his own privilege.

“I know from my experience then, as well as my experience as a social worker, that it’s the black guys who got arrested more often and went to jail more, and then have to deal with finding a job after that,” Fask says. “If they got caught, upper-middle-class kids go to rehab for weed. Or nothing would happen, and they’d continue to college. Poor black kids end up in jail for weed.” He also recognizes that when it came time for college, he was able to go away to a small school, which, like Houser, he needed. “I had that opportunity because my parents had the wherewithal to make it happen,” he says.

Regarding the study, Fask remembers the interview at 21 years old as “intense and emotional,” but adds that he always felt like he could trust the researchers, who never came across as judgmental in the way that parents or school principals were likely to. Given his firsthand experience, he wasn’t surprised by the overwhelming odds, captured in the study, stacked against his more disadvantaged cohorts seeking a college education. But he was struck by the data regarding the still-long odds facing disadvantaged black males seeking good-paying, blue-collar jobs. “It shouldn’t be only a special case or spectacular individual that is able to succeed,” Fask says.

Another participant attending the dinner with Houser and Fask is Qwan Finch, who grew up near Franklin Square, the neighborhood depicted in David Simon’s and Edward Burns’s book, and later HBO show, The Corner. Next to him, Dante Washington recalls being raised in East Baltimore by a single mother, who worked for the school system, after his father died. He completed his bachelor’s degree in his mid-30s from Strayer University and works for a publishing company.

“Sometimes, I’ll talk with friends about the powdered milk, the blocks of cheese, and cans of peanut butter, and we’ll reminisce and laugh about it, but we were grateful, too,” says Finch, a transportation officer with the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. “Looking back, you realize that it’s not everyone’s experience to walk home from school and see prostitutes, guys on the corner selling drugs. I remember being asked if I was afraid, growing up, of stray bullets or whatever, but you’re not because you don’t know anything different.”

It was not a pretty picture, and it got less so over time.

Finch says he was determined not to become “another statistic”—by no means hyperbole. It’s not unfair to describe success for many participants as simply staying out of prison and surviving. Of the 790 first-grade students, at least 26 did not reach their 28th birthdays—a death rate nearly four times the national average.

Nonetheless, he says, it’s still odd now to think of people researching his life, which, he insists, wasn’t all bad—another point, counterintuitively, perhaps, illustrated in the study. Even in challenging neighborhoods, like Franklin Square, most adults are working, some earning middle-class paychecks, doing their best to live a positive life.

“My family was close, the people in the neighborhood were close,” Finch says. “I love Baltimore. My friends love Baltimore.” At the same time, says Finch, who attended the Community College of Baltimore County for three semesters and coaches little league football, “My wife and I want to do better for our two boys.”

Joanne Fennessey and Anna Stoll were secretaries when the Beginning School Study launched, but soon they started helping with research. Armed with note pads—and later tape recorders and portable photocopiers for copying school records—the tiny women would make their way to the schools and homes of their subjects, sometimes in the most compromised parts of town.

“I remember Karl [Alexander] and myself in one row house in South Baltimore, him sitting on a mattress on the living-room floor, and the mother calling out to her husband to get her another beer as he was asking questions,” Fennessey says. “I remember the track marks on another mother’s arm, too.”

As researchers, they couldn’t intervene.

“We couldn’t really do anything other than offer phone numbers or brochures about where they could get some resources,” Fennessey says. “It could be heartbreaking.”

They recall grading kids on a depression scale, and Fennessey recalls listening to several mention suicide attempts. They also recall heading to the same high school multiple times, looking for students who were listed as enrolled, only to realize that, for all intents and purposes, they had dropped out. “The schools didn’t report them as dropped out because they wanted their numbers to look good, and it’s illegal to drop out before your 16th birthday,” Stoll says. “But the kids had stopped going and no one was checking up on them, except us.”

Joanne Fennessey, left, and Anna Stoll became quasi-private detectives in tracking down the study’s participants over a 20-year span.

Fennessey also says the former Southern High School (since rebranded as Digital Harbor High School) in the early ’90s was as frightening as any prison she visited, with students staying home because they were afraid of the violence there.

Reflecting on the study, Alexander and Olson note that although it was discouraging to see disadvantaged students fall behind academically each summer—it was encouraging to see that they progressed as much during the school year as more advantaged students. Their recommendations include more pre-school and early elementary intervention, as well as higher-quality after-school and summer-school programs for disadvantaged kids, who quickly lose ground without the infrastructure and influence of school.

“However, it can’t only be more tedious homework, longer school hours, and keeping these kids in school all summer,” adds Lenora Fulani, a developmental psychology Ph.D. who has presented her work alongside Alexander at places like Stanford University. “These kids need to get out of their neighborhoods, too. This is about development as well as learning, and there’s a difference. They need to travel, go on field trips, and go to museums. Kids from more advantaged backgrounds don’t have bigger brains,” says Fulani, “they have bigger lives.”

At the same time, Alexander and the other researchers acknowledge it’s unlikely that a large urban school system can turn around without the neighborhoods around them dramatically improving. It’s poverty that leads to failing schools, not the other way around, in other words.

Today, however, the two questions Alexander is most often asked aren’t directly tied to the study’s findings.

“People want to know if I thought about keeping it going longer,” he says. “But Doris had already put off retirement, and there wasn’t anybody else to hand it off to.”

He adds there has also been other research done showing that the disparate income levels, which are diverging at 28, only grow farther apart in middle age. For example, the wages of a warehouse employee and someone just passing the bar may not be that different at 28, but their income potential over time grows apart exponentially. “There’s plenty of evidence that predicts how things will go from here,” Alexander says.

The other question he gets asked is whether he believes that, by participating in the study, students benefitted in any significant way. There is, after all, the theory about observation invariably affecting the nature of what is being observed.

“I wish that was the case, is all I can say,” Alexander says with a shrug. “It would be an easy solution.”